Virgil, Priest of Apollo?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dionysus, Wine, and Tragic Poetry: a Metatheatrical Reading of P.Koln VI 242A=Trgf II F646a Anton Bierl

BIERL, ANTON, Dionysus, Wine, and Tragic Poetry: A Metatheatrical Reading of a New Dramatic Papyrus , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 31:4 (1990:Winter) p.353 Dionysus, Wine, and Tragic Poetry: A Metatheatrical Reading of P.Koln VI 242A=TrGF II F646a Anton Bierl EW DRAMATIC PAPYRUS1 confronts interpreters with many ~puzzling questions. In this paper I shall try to solve some of these by applying a new perspective to the text. I believe that this fragment is connected with a specific literary feature of drama especially prominent in the bnal decades of the bfth century B.C., viz. theatrical self-consciousness and the use of Dionysus, the god of Athenian drama, as a basic symbol for this tendency. 2 The History of the Papyrus Among the most important papyri brought to light by Anton Fackelmann is an anthology of Greek prose and poetry, which includes 19 verses of a dramatic text in catalectic anapestic tetrameters. Dr Fackelmann entrusted the publication of this papyrus to Barbel Kramer of the University of Cologne. Her editio princeps appeared in 1979 as P. Fackelmann 5. 3 Two years later the verses were edited a second time by Richard Kannicht and Bruno Snell and integrated into the Fragmenta Adespota in 1 This papyrus has already been treated by the author in Dionysos und die griechische Trag odie. Politische und 'metatheatralische' Aspekte im Text (Tiibingen 1991: hereafter 'Bieri') 248-53. The interpretation offered here is an expansion of my earlier provisional comments in the Appendix, presenting fragments of tragedy dealing with Dionysus. 2 See C. -

From the Odyssey, Part 1: the Adventures of Odysseus

from The Odyssey, Part 1: The Adventures of Odysseus Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald ANCHOR TEXT | EPIC POEM Archivart/Alamy Stock Photo Archivart/Alamy This version of the selection alternates original text The poet, Homer, begins his epic by asking a Muse1 to help him tell the story of with summarized passages. Odysseus. Odysseus, Homer says, is famous for fighting in the Trojan War and for Dotted lines appear next to surviving a difficult journey home from Troy.2 Odysseus saw many places and met many the summarized passages. people in his travels. He tried to return his shipmates safely to their families, but they 3 made the mistake of killing the cattle of Helios, for which they paid with their lives. NOTES Homer once again asks the Muse to help him tell the tale. The next section of the poem takes place 10 years after the Trojan War. Odysseus arrives in an island kingdom called Phaeacia, which is ruled by Alcinous. Alcinous asks Odysseus to tell him the story of his travels. I am Laertes’4 son, Odysseus. Men hold me formidable for guile5 in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca6 under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,7 loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea,8 the enchantress, desired me, and detained me in her hall. -

The Odyssey Homer Translated Lv Robert Fitzç’Erald

I The Odyssey Homer Translated lv Robert Fitzç’erald PART 1 FAR FROM HOME “I Am Odysseus” Odysseus is in the banquet hail of Alcinous (l-sin’o-s, King of Phaeacia (fë-a’sha), who helps him on his way after all his comrades have been killed and his last vessel de stroyed. Odysseus tells the story of his adventures thus far. ‘I am Laertes’ son, Odysseus. [aertes Ia Men hold me formidable for guile in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca 4 Ithaca ith’. k) ,in island oft under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, the west e ast it C reece. in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I (I 488 An Epic Poem I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,’ 12. Calypso k1ip’sö). loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves, to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea, the enchantress, 15 15. Circe (sür’së) of Aeaea e’e-). desired me, and detained me in her hail. But in my heart I never gave consent. Where shall a man find sweetness to surpass his OWfl home and his parents? In far lands he shall not, though he find a house of gold. -

The Odyssey Homer Translated by Robert Fitzgerald

The Wanderings of Odysseus from The Odyssey Homer Translated by Robert Fitzgerald Book Nine: new Coasts and poseidon’s son ―What shall I say first? What shall I keep until the end? What conflict is introduced in Odysseus’ initial statements at the banquet? The gods have tried1 me in a thousands ways. What do these statements indicate about the kind of journey he has had? But first my name: Let that be known to you, 5 and if I pull away from pitiless death, friendship will bind us, though my land lies far. Now this was the reply Odysseus made: . ―I am Laertes‘ son, Odysseus. How are Odysseus’ comments about himself during his speech at Men hold2 me Alcinous’ banquet appropriate for an epic hero? formidable for guile in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky‘s rim. 10 My home is on the peaked seamark of Ithaca under Mount Neion‘s windblown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Doulikhion, Same, wooded Zakynthos—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, 15 and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy‘s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, Odysseus refers to two beautiful goddesses, Calypso and Circe, who have though I have been detained long by Calypso, delayed him on their islands. (Details about Circe appear in Book 10.) loveliest among goddesses, who held me Notice, however, that Odysseus seems nostalgic for his own family and 20 in her smooth caves, to be her heart‘s delight, homeland. -

THE ODYSSEY of HOMER Translated by WILLIAM COWPER LONDON: PUBLISHED by J·M·DENT·&·SONS·LTD and in NEW YORK by E·P·DUTTON & CO to the RIGHT HONOURABLE

THE ODYSSEY OF HOMER Translated by WILLIAM COWPER LONDON: PUBLISHED by J·M·DENT·&·SONS·LTD AND IN NEW YORK BY E·P·DUTTON & CO TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE COUNTESS DOWAGER SPENCER THE FOLLOWING TRANSLATION OF THE ODYSSEY, A POEM THAT EXHIBITS IN THE CHARACTER OF ITS HEROINE AN EXAMPLE OF ALL DOMESTIC VIRTUE, IS WITH EQUAL PROPRIETY AND RESPECT INSCRIBED BY HER LADYSHIP’S MOST DEVOTED SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. THE ODYSSEY OF HOMER TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH BLANK VERSE BOOK I ARGUMENT In a council of the Gods, Minerva calls their attention to Ulysses, still a wanderer. They resolve to grant him a safe return to Ithaca. Minerva descends to encourage Telemachus, and in the form of Mentes directs him in what manner to proceed. Throughout this book the extravagance and profligacy of the suitors are occasionally suggested. Muse make the man thy theme, for shrewdness famedAnd genius versatile, who far and wideA Wand’rer, after Ilium overthrown,Discover’d various cities, and the mindAnd manners learn’d of men, in lands remote.He num’rous woes on Ocean toss’d, endured,Anxious to save himself, and to conductHis followers to their home; yet all his carePreserved them not; they perish’d self-destroy’dBy their own fault; infatuate! who devoured10The oxen of the all-o’erseeing Sun,And, punish’d for that crime, return’d no more.Daughter divine of Jove, these things record,As it may please thee, even in our ears.The rest, all those who had perdition ’scapedBy war or on the Deep, dwelt now at home;Him only, of his country and his wifeAlike desirous, in her hollow grotsCalypso, Goddess beautiful, detainedWooing him to her arms. -

Dionysus and Ariadne in the Light of Antiocheia and Zeugma Mosaics

Anatolia Antiqua Revue internationale d'archéologie anatolienne XXIII | 2015 Varia Dionysus and Ariadne in the light of Antiocheia and Zeugma Mosaics Şehnaz Eraslan Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/anatoliaantiqua/345 DOI: 10.4000/anatoliaantiqua.345 Publisher IFEA Printed version Date of publication: 1 June 2015 Number of pages: 55-61 ISBN: 9782362450600 ISSN: 1018-1946 Electronic reference Şehnaz Eraslan, « Dionysus and Ariadne in the light of Antiocheia and Zeugma Mosaics », Anatolia Antiqua [Online], XXIII | 2015, Online since 30 June 2018, connection on 18 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/anatoliaantiqua/345 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/anatoliaantiqua. 345 Anatolia Antiqua TABLE DES MATIERES Hélène BOUILLON, On the anatolian origins of some Late Bronze egyptian vessel forms 1 Agneta FRECCERO, Marble trade in Antiquity. Looking at Labraunda 11 Şehnaz ERASLAN, Dionysus and Ariadne in the light of Antiocheia and Zeugma Mosaics 55 Ergün LAFLI et Gülseren KAN ŞAHİN, Middle Byzantine ceramics from Southwestern Paphlagonia 63 Mustafa AKASLAN, Doğan DEMİRCİ et Özgür PERÇİN en collaboration avec Guy LABARRE, L’église paléochrétienne de Bindeos (Pisidie) 151 Anaïs LAMESA, La chapelle des Donateurs à Soğanlı, nouvelle fondation de la famille des Sképidès 179 Martine ASSENAT et Antoine PEREZ, Localisation et chronologie des moulins hydrauliques d’Amida. A propos d’Ammien Marcellin, XVIII, 8, 11 199 Helke KAMMERER-GROTHAUS, »Ubi Troia fuit« Atzik-Köy - Eine Theorie von Heinrich Nikolaus Ulrichs (1843) -

THE CYCLOPS) PHILOSOPHY on First Glance, This Story Appears to Be the Least Yielding When It Comes to Finding Philosophy for Discussion

NOBODY'S HOME (THE CYCLOPS) PHILOSOPHY On first glance, this story appears to be the least yielding when it comes to finding philosophy for discussion. But take a closer look and the philosophy starts to materialise from nothing. I say 'materialise from nothing' because I have found the most successful philosophical discussion emerging from this session to be about non-existent entities. This topic emerges from both the content of the story (i.e. his use of the word 'nobody' to trick the Cyclops – 'nobody' seeming to be a referring term for someone that isn't there) and a feature of the story (i.e. that it contains a famous mythical creature – mythical creatures being perfect examples of non-existent entities). So, how can something that doesn't exist have certain qualities or features? Does our collective reference to a Cyclops somehow give it existence, perhaps in our minds, in our culture, or in some other way? Some philosophers have thought so. If so, what kind of existence would this be? It's certainly not the kind of existence something like a rabbit has. Or is it simply that a Cyclops does not exist in any way? But if this is the case, how can you meaningfully speak about one - how can you tell the story you are about to tell? Note: this story contains a clear example of a key Ancient Greek theme and one that runs throughout the Odyssey: hubris, 'downfall brought about by excessive pride'. Odysseus' announcement revealing his true identity to Polyphemus from the prow of his ship endangers both himself and his crew by inciting the wrath of the god Poseidon no less. -

Generosa Sangco-Jackson Agon Round NJCL 2014.Pdf

NJCL Ἀγών 2014 Round 1 1. What Athenian archon was responsible for passing the seisachtheia, outlawing enslavement to pay off debt? SOLON B1: In what year was Solon elected archon? 594 B.C. B2: Name one of the two political parties that formed after Solon’s reforms. THE COAST / THE PLAIN 2. What is the meaning of the Greek noun θάλαττα? SEA B1: Change θάλαττα to the genitive singular. θαλάττης B2: Change θαλάττης to the accusative singular. θάλατταν 3. "Sing, muse, the wrath of Achilles" is the first line of what work of Greek literature? ILIAD B1: Into how many books is the Iliad divided? 24 B2: In which book of Homer's Iliad does the archer Pandarus break the truce between the Greeks and Trojans? BOOK 4 4. What is the meaning of the Greek adjective from which "sophisticated" is derived? WISE, SKILLED (σοφός) B1: What derivative of σοφός is an oxymoronic word meaning “wise fool”? SOPHOMORE B2: What derivative of σοφός applies to a person who reasons with clever but fallacious arguments, particularly with a disregard to the truth. SOPHIST 5. What hunter in mythology was blinded by king Oenopion on Chios for drunkenly violating his daughter Merope? ORION B1: When Orion regained his sight and returned to Chios for revenge, how did the king save himself from Orion’s murderous intentions? HE HID IN AN UNDERGROUND CHAMBER B2: Which of the Olympians had fashioned this chamber? HEPHAESTUS 6. What king of Pylos, known as the Gerenian charioteer, was renown for his wisdom during the Trojan war? NESTOR B1: Who was Nestor’s father, who demanded Phylacus’ cattle as the bride-price for his daughter Pero? NELEUS B2: What young son of Amythaon and Idomene eventually offered up the bride- price and married Pero? BIAS 7. -

Back-To-Back Synopses.Indd

Storykit: Back-to-back Synopses Short Synopsis (in 3s!) for ease of memorisation: The Wooden Horse 1. The Greeks go to war with the Trojans. 2. Odysseus comes up with the Wooden Horse ploy. 3. The Greeks win the war. The Ciconians 1. They are brought to the Ciconian shores by a freak wind. 2. The Greeks attack them because they were allies of Troy. 3. The Ciconians attack them back and the Greeks are forced to retreat. The Lotus Eaters 1. Arrive on a wooded isle and lose a searching-garrison. 2. Go in search and find them drinking the juice of happiness and forgetting. 3. Just get away before they are all stuck on the island under the influence of the juice. The Cyclops 1. Arrive on a barren island and search it. 2. Find the home of the Cyclops and are trapped in it. 3. Odysseus (‘Nobody’) tricks his way out, blinding the Cyclops, and they just escape. http://education.worley2.continuumbooks.com © Peter Worley (2012) The If Odyseey. London: Bloomsbury Illustrations © Tamar Levi 2012 Aeolus 1. Arrive on a fortified island and are finally welcomed as guests. 2. Odysseus is given a bag as a gift by Aeolus. 3. Crew mutiny just as they reach home and release the winds from inside the bag, blowing them back out to sea. The Laestrygonians 1. Arrive on another island with an encircled harbour. 2. Find out the hard way that this is an island of giant cannibals. 3. They only just escaped with their lives. Circe 1. Arrive on yet another island only for some of the men to be turned into pigs by the goddess Circe. -

Story 1: the Cicones

THE WANDERINGS OF ODYSSEUS – STORIES 1-11 STORY 1: THE CICONES THE WANDERINGS OF ODYSSEUS – STORIES 1-11 (OF 30) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 THE CICONES SHIP AND CREW COUNT BEFORE AFTER 12 Ships 12 Ships 608 Men 536 Men After ten long years, the Trojan War is over. The ACHAEANS (a name for the Greeks) have defeated the Trojans. ODYSSEUS, his men, and their twelve ships, begin their journey home to ITHACA. The storm winds take them to the land of the CICONES where Odysseus and his men sack the main city Ismarus, attack their people, and steal their possessions. Odysseus and each of his men share the stolen riches equally. Odysseus urges that they leave. The crew do not listen. They slaughter the Cicones’ sheep and cattle, and drink their wine. The Cicones call for help. Now stronger and larger in number, the Cicones fight back with force. Odysseus loses six men from each of his twelve ships. He feels he and his men are being punished by ZEUS. Odysseus and the rest of his crew sail away before any more men are killed. BOOK AND LINE REFERENCES BOOK 9 (OF 24) Fagles (Fa) Fitzgerald (Fi) Lattimore (La) Lombardo (Lo) 9.44-75 9.43-73 9.39-66 9.42-68 NOTE: The numbers appearing after the Book Number (in this case, Book 9) are the specific line numbers for each translation. Although Book Numbers are the same across all four translations, line numbers are not. If you are using a prose translation (and line numbers aren’t provided), use the Book references provided above; the line numbers can be used to provide an approximate location in that Book for the particular passages. -

Unit 5: Epic and Myth

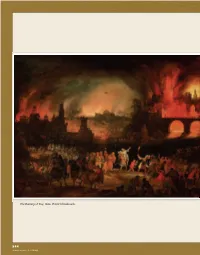

The Burning of Troy, 1606. Pieter Schoubroeck. 944 Archivo Iconografico, S.A./CORBIS UNIT FIVE Epic and Myth Looking Ahead Many centuries ago, before books, magazines, paper, and pencils were invented, people recited their stories. Some of the stories they told offered explanations of natural phenomena, such as thunder and lightning, or the culture’s customs or beliefs. Other stories were meant for entertainment. Taken together, these stories—these myths, epics, and legends—tell a history of loyalty and betrayal, heroism and cowardice, love and rejection. In this unit, you will explore the literary elements that make them unique. PREVIEW Big Ideas and Literary Focus BIG IDEA: LITERARY FOCUS: 1 Journeys Hero BIG IDEA: LITERARY FOCUS: 2 Courage and Cleverness Archetype OBJECTIVES In learning about the genres of epic and myth, • identifying and exploring literary elements you will focus on the following: significant to the genres • understanding characteristics of epics and myths • analyzing the effect that these literary elements have upon the reader 945 Genre Focus: Epic and Myth What is unique about epics and myths? Why do we read stories from the distant past? answer. He thought that in order for us to under- Why should we care about heroes and villains long stand the people we are today, we have to learn dead? About cities and palaces that were destroyed about those who came before us. One way to do centuries before our time? The noted psychologist that, Jung believed, was to read the myths and and psychiatrist Carl Jung thought he knew the epics of long ago. -

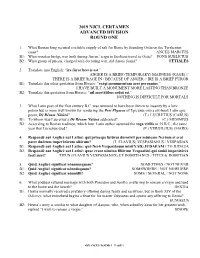

2019 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2019 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. What Roman king secured a reliable supply of salt for Rome by founding Ostia on the Tyrrhenian coast? ANCUS MARCIUS B1: What wooden bridge was built during Ancus’ reign to facilitate travel to Ostia? PONS SUBLICIUS B2: What group of priests, charged with declaring war, did Ancus found? FĒTIĀLĒS 2. Translate into English: “īra fūror brevis est.” ANGER IS A BRIEF (TEMPORARY) MADNESS (RAGE) // THERE IS A BRIEF RAGE IN / BECAUSE OF ANGER // IRE IS A BRIEF FUROR B1: Translate this other quotation from Horace: “exēgī monumentum aere perennius.” I HAVE BUILT A MONUMENT MORE LASTING THAN BRONZE B2: Translate this quotation from Horace: “nīl mortālibus arduī est.” NOTHING IS DIFFICULT FOR MORTALS 3. What Latin poet of the first century B.C. was rumored to have been driven to insanity by a love potion but is more well known for rendering the Peri Physeos of Epicurus into a six-book Latin epic poem, Dē Rērum Nātūrā? (T.) LUCRETIUS (CARUS) B1: To whom was Lucretius’s Dē Rērum Nātūrā addressed? (C.) MEMMIUS B2: According to Roman tradition, which later Latin author assumed the toga virīlis in 55 B.C., the same year that Lucretius died? (P.) VERGIL(IUS) (MARO) 4. Respondē aut Anglicē aut Latīnē: quī prīnceps futūrus dormīvit per mūsicam Nerōnis et erat pater duōrum imperātōrum aliōrum? (T. FLAVIUS) VESPASIANUS / VESPASIAN B1: Respondē aut Anglicē aut Latine: quō Nerō Vespasiānum mīsit?(AD) JUDAEAM / TO JUDAEA B2: Respondē aut Anglicē aut Latīnē: quae erant nōmina fīliōrum Vespasiānī quī ambō imperātōrēs factī sunt? TITUS (FLAVIUS VESPASIANUS) ET DOMITIANUS / TITUS & DOMITIAN 5.