© Copyright 2017 Alberto A. Requejo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Odyssey, Part 1: the Adventures of Odysseus

from The Odyssey, Part 1: The Adventures of Odysseus Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald ANCHOR TEXT | EPIC POEM Archivart/Alamy Stock Photo Archivart/Alamy This version of the selection alternates original text The poet, Homer, begins his epic by asking a Muse1 to help him tell the story of with summarized passages. Odysseus. Odysseus, Homer says, is famous for fighting in the Trojan War and for Dotted lines appear next to surviving a difficult journey home from Troy.2 Odysseus saw many places and met many the summarized passages. people in his travels. He tried to return his shipmates safely to their families, but they 3 made the mistake of killing the cattle of Helios, for which they paid with their lives. NOTES Homer once again asks the Muse to help him tell the tale. The next section of the poem takes place 10 years after the Trojan War. Odysseus arrives in an island kingdom called Phaeacia, which is ruled by Alcinous. Alcinous asks Odysseus to tell him the story of his travels. I am Laertes’4 son, Odysseus. Men hold me formidable for guile5 in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca6 under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,7 loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea,8 the enchantress, desired me, and detained me in her hall. -

Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12 Erika Zimmerman Damer University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Classical Studies Faculty Publications Classical Studies 2016 Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12 Erika Zimmerman Damer University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/classicalstudies-faculty- publications Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Damer, Erika Zimmermann. "Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12." Helios 43, no. 1 (2016): 55-85. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classical Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classical Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12 ERIKA ZIMMERMANN DAMER When in Book 1 of his Epistles Horace reflects back upon the beginning of his career in lyric poetry, he celebrates his adaptation of Archilochean iambos to the Latin language. He further states that while he followed the meter and spirit of Archilochus, his own iambi did not follow the matter and attacking words that drove the daughters of Lycambes to commit suicide (Epist. 1.19.23–5, 31).1 The paired erotic invectives, Epodes 8 and 12, however, thematize the poet’s sexual impotence and his disgust dur- ing encounters with a repulsive sexual partner. The tone of these Epodes is unmistakably that of harsh invective, and the virulent targeting of the mulieres’ revolting bodies is precisely in line with an Archilochean poetics that uses sexually-explicit, graphic obscenities as well as animal compari- sons for the sake of a poetic attack. -

Lecture 19 Greek, Carthaginian, and Roman Agricultural Writers

Lecture 19 1 Lecture 19 Greek, Carthaginian, and Roman Agricultural Writers Our knowledge of the agricultural practices of Greece and Rome are based on writings of the period. There were an enormous number of writings on agriculture, although most of them are lost we know about them from references made by others. Theophrastus of Eresos (387–287 BCE) The two botanical treatises of Theophrastus are the greatest treasury of botanical and horticultural information from antiquity and represent the culmination of a millenium of experience, observation, and science from Egypt and Mesopotamia. The fi rst work, known by its Latin title, Historia de Plantis (Enquiry into Plants), and composed of nine books (chapters is a better term), is largely descriptive. The second treatise, De Causis Plantarum (Of Plants, an Explanation), is more philosophic, as indicated by the title. The works are lecture notes rather than textbooks and were presumably under continual revision. The earliest extant manuscript, Codex Urbinas of the Vatican Library, dates from the 11th century and contains both treatises. Although there have been numerous editions, translations, and commentaries, Theophrastus the only published translation in En glish of Historia de Plantis is by (appropriately) Sir Arthur Hort (1916) and of De Causis Plantarum is by Benedict Einarson and George K.K. Link (1976). Both are available as volumes of the Loeb Classical Library. Theophrastus (divine speaker), the son of a fuller (dry cleaner using clay), was born at Eresos, Lesbos, about 371 BCE and lived to be 85. His original name, Tyrtamos, was changed by Aristotle because of his oratorical gifts. -

The Odyssey Homer Translated Lv Robert Fitzç’Erald

I The Odyssey Homer Translated lv Robert Fitzç’erald PART 1 FAR FROM HOME “I Am Odysseus” Odysseus is in the banquet hail of Alcinous (l-sin’o-s, King of Phaeacia (fë-a’sha), who helps him on his way after all his comrades have been killed and his last vessel de stroyed. Odysseus tells the story of his adventures thus far. ‘I am Laertes’ son, Odysseus. [aertes Ia Men hold me formidable for guile in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca 4 Ithaca ith’. k) ,in island oft under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, the west e ast it C reece. in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I (I 488 An Epic Poem I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,’ 12. Calypso k1ip’sö). loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves, to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea, the enchantress, 15 15. Circe (sür’së) of Aeaea e’e-). desired me, and detained me in her hail. But in my heart I never gave consent. Where shall a man find sweetness to surpass his OWfl home and his parents? In far lands he shall not, though he find a house of gold. -

The Odyssey Homer Translated by Robert Fitzgerald

The Wanderings of Odysseus from The Odyssey Homer Translated by Robert Fitzgerald Book Nine: new Coasts and poseidon’s son ―What shall I say first? What shall I keep until the end? What conflict is introduced in Odysseus’ initial statements at the banquet? The gods have tried1 me in a thousands ways. What do these statements indicate about the kind of journey he has had? But first my name: Let that be known to you, 5 and if I pull away from pitiless death, friendship will bind us, though my land lies far. Now this was the reply Odysseus made: . ―I am Laertes‘ son, Odysseus. How are Odysseus’ comments about himself during his speech at Men hold2 me Alcinous’ banquet appropriate for an epic hero? formidable for guile in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky‘s rim. 10 My home is on the peaked seamark of Ithaca under Mount Neion‘s windblown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Doulikhion, Same, wooded Zakynthos—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, 15 and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy‘s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, Odysseus refers to two beautiful goddesses, Calypso and Circe, who have though I have been detained long by Calypso, delayed him on their islands. (Details about Circe appear in Book 10.) loveliest among goddesses, who held me Notice, however, that Odysseus seems nostalgic for his own family and 20 in her smooth caves, to be her heart‘s delight, homeland. -

Zur Antiken Georgica—Rezeption

ZUR ANTIKEN GEORGICA—REZEPTION Mitunter geben antike Leser der Georgica zu erkennen, welche Hauptaussagen ihnen das Werk zu enthalten schien. Im folgenden geht es also um diejenigen der vielen antiken Georgica-Erwähnungen und Zitate, die direkt oder indirekt eine Auffassung des Gesamtwerkes verraten. Im Mittelpunkt sollen Äußerungen des ersten Jahrhunderts nach Chr. stehen. Die Untersuchung ist im wesentlichen zwei geteilt: (I) GeorgicaRezeption bei Laien, (II) GeorgicaRezeption bei Landwirt schaftsspezialisten. In einer abschließenden Überlegung sollen kurz einige Folge rungen für die moderne Interpretation erörtert werden (III). I Zunächst ein Beispiel aus Quintilian: beim ersten Unterricht darf man nicht zu streng sein — sonst entmutigt man die Anfänger (inst. 2,4,11). Das wird von Quintilian mit einer VirgilReminiszenz verdeutlicht. Der Dichter hatte gelehrt (G 2,36270), einjährige Weinstöcke dürfe man noch nicht mit dem Messer be schneiden — Begründung: ante reformidant ferrum. Quintilian wendet das nun auf die Schüler an erstaunlicherweise aber nicht als Virgilbezug, sondern als Bauern wissen: ,JJas wissen auch die Landleute" — quod etiam rusticis notum est — „die glauben, an das zarte Laub dürfe man noch nicht die Sichel anlegen, weil es das Eisen offenbar scheut" —quia reformidare ferrum videntur. Die virgilischen Entleh nungen sind (auch über das hier gegebene Virgilzitat hinaus) deutlich, aber Virgils Lehre wird von Quintilian völlig mit Bauernwissen identifiziert; der Name Virgils erscheint nicht. Für unser modernes GeorgicaVerständnis ist es überraschend, daß Virgil sozusagen nur noch als Quelle für bäuerliches Fachwissen gelten soll. Dieser volksnahe und fachliche Aspekt ist modernen Interpreten wohl ganz verborgen ge blieben, wenn sie die Georgica ausschließlich als ein kompliziertes Werk für eine hochgebüdete Leserschaft deuten. -

On Some Tibullian Problems

The Classical Quarterly http://journals.cambridge.org/CAQ Additional services for The Classical Quarterly: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here On some Tibullian Problems J. P. Postgate The Classical Quarterly / Volume 3 / Issue 02 / April 1909, pp 127 - 131 DOI: 10.1017/S0009838800018334, Published online: 11 February 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0009838800018334 How to cite this article: J. P. Postgate (1909). On some Tibullian Problems. The Classical Quarterly, 3, pp 127-131 doi:10.1017/S0009838800018334 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/CAQ, IP address: 193.61.135.80 on 27 Mar 2015 ON SOME TIBULLIAN PROBLEMS. I. THE FEAST OF LUSTRATION IN II. i. DISSATISFIED with current views upon the exordium of Tibullus II. i. (vv. 1-24), I proposed in Selections from Tibullus (1903) to make the occasion of the poem the Sementiuae Feriae instead of the Ambarualia. This proposal, criticised, amongst others, by Mr. Warde Fowler in an interesting article in the Classical Review (xxii. 1908, pp. 36 sqq.), I have now abandoned (ib. p. \oti). But the difficulties which led me to break away from previous exegesis still remain, and to them I address myself in the present article. I shall assume that these difficulties do not arise from lax or ' poetical' treatment of facts, and that here, as elsewhere, Tibullus writes upon rustic matters with adequate knowledge and care. Let us collect the indications which he gives of the season of the festival which he is here describing. -

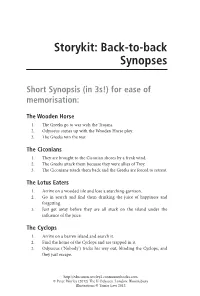

Back-To-Back Synopses.Indd

Storykit: Back-to-back Synopses Short Synopsis (in 3s!) for ease of memorisation: The Wooden Horse 1. The Greeks go to war with the Trojans. 2. Odysseus comes up with the Wooden Horse ploy. 3. The Greeks win the war. The Ciconians 1. They are brought to the Ciconian shores by a freak wind. 2. The Greeks attack them because they were allies of Troy. 3. The Ciconians attack them back and the Greeks are forced to retreat. The Lotus Eaters 1. Arrive on a wooded isle and lose a searching-garrison. 2. Go in search and find them drinking the juice of happiness and forgetting. 3. Just get away before they are all stuck on the island under the influence of the juice. The Cyclops 1. Arrive on a barren island and search it. 2. Find the home of the Cyclops and are trapped in it. 3. Odysseus (‘Nobody’) tricks his way out, blinding the Cyclops, and they just escape. http://education.worley2.continuumbooks.com © Peter Worley (2012) The If Odyseey. London: Bloomsbury Illustrations © Tamar Levi 2012 Aeolus 1. Arrive on a fortified island and are finally welcomed as guests. 2. Odysseus is given a bag as a gift by Aeolus. 3. Crew mutiny just as they reach home and release the winds from inside the bag, blowing them back out to sea. The Laestrygonians 1. Arrive on another island with an encircled harbour. 2. Find out the hard way that this is an island of giant cannibals. 3. They only just escaped with their lives. Circe 1. Arrive on yet another island only for some of the men to be turned into pigs by the goddess Circe. -

Ancient Authors 297

T Ancient authors 297 is unknown. His Attic Nights is a speeches for the law courts, collection of essays on a variety political speeches, philosophical ANCIENT AUTHORS of topics, based on his reading of essays, and personal letters to Greek and Roman writers and the friends and family. : (fourth century AD) is the lectures and conversations he had Apicius Columella: Lucius Iunius name traditionally given to the heard. The title Attic Nights refers Moderatus Columella (wrote c.AD to Attica, the district in Greece author of a collection of recipes, 60–65) was born at Gades (modern de Re Coquinaria On the Art of around Athens, where Gellius was ( Cadiz) in Spain and served in the Cooking living when he wrote the book. ). Marcus Gavius Apicius Roman army in Syria. He wrote a was a gourmet who lived in the Cassius Dio (also Dio Cassius): treatise on farming, de Re Rustica early first centuryAD and wrote Cassius Dio Cocceianus (c.AD (On Farming). about sauces. Seneca says that he 150–235) was born in Bithynia. He Diodorus Siculus: Diodorus claimed to have created a scientia had a political career as a consul (wrote c.60–30 BC) was a Greek popīnae (snack bar cuisine). in Rome and governor of the from Sicily who wrote a history of provinces of Africa and Dalmatia. Appian: Appianos (late first the world centred on Rome, from century AD–AD 160s) was born in His history of Rome, written in legendary beginnings to 54 BC. Greek, covers the period from Alexandria, in Egypt, and practised Much of the original forty books Aeneas’ arrival in Italy to AD 229. -

Story 1: the Cicones

THE WANDERINGS OF ODYSSEUS – STORIES 1-11 STORY 1: THE CICONES THE WANDERINGS OF ODYSSEUS – STORIES 1-11 (OF 30) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 THE CICONES SHIP AND CREW COUNT BEFORE AFTER 12 Ships 12 Ships 608 Men 536 Men After ten long years, the Trojan War is over. The ACHAEANS (a name for the Greeks) have defeated the Trojans. ODYSSEUS, his men, and their twelve ships, begin their journey home to ITHACA. The storm winds take them to the land of the CICONES where Odysseus and his men sack the main city Ismarus, attack their people, and steal their possessions. Odysseus and each of his men share the stolen riches equally. Odysseus urges that they leave. The crew do not listen. They slaughter the Cicones’ sheep and cattle, and drink their wine. The Cicones call for help. Now stronger and larger in number, the Cicones fight back with force. Odysseus loses six men from each of his twelve ships. He feels he and his men are being punished by ZEUS. Odysseus and the rest of his crew sail away before any more men are killed. BOOK AND LINE REFERENCES BOOK 9 (OF 24) Fagles (Fa) Fitzgerald (Fi) Lattimore (La) Lombardo (Lo) 9.44-75 9.43-73 9.39-66 9.42-68 NOTE: The numbers appearing after the Book Number (in this case, Book 9) are the specific line numbers for each translation. Although Book Numbers are the same across all four translations, line numbers are not. If you are using a prose translation (and line numbers aren’t provided), use the Book references provided above; the line numbers can be used to provide an approximate location in that Book for the particular passages. -

Some Imitations of Pindar and Sappho by Horace

Some imitations of Pindar and Sappho by Horace The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Nagy, Gregory. 2015.12.31. "Some imitations of Pindar and Sappho by Horace." Classical Inquiries. http://nrs.harvard.edu/ urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries. Published Version https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/some-imitations-of- pindar-and-sappho-by-horace/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:39699959 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Classical Inquiries Editors: Angelia Hanhardt and Keith Stone Consultant for Images: Jill Curry Robbins Online Consultant: Noel Spencer About Classical Inquiries (CI ) is an online, rapid-publication project of Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, devoted to sharing some of the latest thinking on the ancient world with researchers and the general public. While articles archived in DASH represent the original Classical Inquiries posts, CI is intended to be an evolving project, providing a platform for public dialogue between authors and readers. Please visit http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries for the latest version of this article, which may include corrections, updates, or comments and author responses. Additionally, many of the studies published in CI will be incorporated into future CHS pub- lications. Please visit http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.eresource:CHS.Online_Publishing for a complete and continually expanding list of open access publications by CHS. -

Tractatio, Re-Tractatio, Revisionist History

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-41680-1 — Carthage in Virgil's Aeneid Elena Giusti Excerpt More Information 1 INTRODUCTION: TRACTATIO, RE- TRACTATIO, REVISIONIST HISTORY … what a change there has been! Clio, Muse of History, has moved massively into the territory of her tragic sister Melpomene. Jasper Grii n 1 How (Not) to Handle History: Horace’s Ode to Pollio Writing under Augustus was no easy task. Think of the poets Cornelius Gallus and Ovid : the former fallen into disgrace by the emperor allegedly for his haughty behaviour as prefect of Egypt and driven to suicide in 27– 26 BCE, 2 the latter relegated to Tomis, on the Black Sea, in 8 CE, because of a carmen and an error , a poem and a mistake. 3 There is also Titus Labienus , an historian of Pompeian cause nicknamed ‘Rabienus’ because of the rabies (‘rage’) of his writings, who committed suicide around 6 CE on hearing that his whole work had been sen- tenced to fl ames (Sen. Controu. 10, praef. 4– 8) – just like the oeuvre of the orator Cassius Severus relegated soon after Labienus’ case for having divulgated libelli which allegedly defamed ‘illustrious men and women’ (Tac. Ann . 1.72). 4 An earlier, and even more intriguing, character is the politician, playwright and historian Asinius Pollio, certainly one of the most distinguished men writing history under Augustus, and a predecessor of Labienus in his supposed ferocia , ‘fi erceness’ (Tac. Ann . 1.12), glossed by Cassius Dio as παα , ‘free 1 Grii n ( 1999 ) 74. 2 But Dio 53.23 also mentions that Gallus divulgated a gossip about Augustus; see also Suet.