Myth Made Fact Lesson 18: Odysseus in Wonderland with Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Odyssey, Part 1: the Adventures of Odysseus

from The Odyssey, Part 1: The Adventures of Odysseus Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald ANCHOR TEXT | EPIC POEM Archivart/Alamy Stock Photo Archivart/Alamy This version of the selection alternates original text The poet, Homer, begins his epic by asking a Muse1 to help him tell the story of with summarized passages. Odysseus. Odysseus, Homer says, is famous for fighting in the Trojan War and for Dotted lines appear next to surviving a difficult journey home from Troy.2 Odysseus saw many places and met many the summarized passages. people in his travels. He tried to return his shipmates safely to their families, but they 3 made the mistake of killing the cattle of Helios, for which they paid with their lives. NOTES Homer once again asks the Muse to help him tell the tale. The next section of the poem takes place 10 years after the Trojan War. Odysseus arrives in an island kingdom called Phaeacia, which is ruled by Alcinous. Alcinous asks Odysseus to tell him the story of his travels. I am Laertes’4 son, Odysseus. Men hold me formidable for guile5 in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca6 under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,7 loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea,8 the enchantress, desired me, and detained me in her hall. -

The Odyssey Homer Translated Lv Robert Fitzç’Erald

I The Odyssey Homer Translated lv Robert Fitzç’erald PART 1 FAR FROM HOME “I Am Odysseus” Odysseus is in the banquet hail of Alcinous (l-sin’o-s, King of Phaeacia (fë-a’sha), who helps him on his way after all his comrades have been killed and his last vessel de stroyed. Odysseus tells the story of his adventures thus far. ‘I am Laertes’ son, Odysseus. [aertes Ia Men hold me formidable for guile in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca 4 Ithaca ith’. k) ,in island oft under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, the west e ast it C reece. in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I (I 488 An Epic Poem I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,’ 12. Calypso k1ip’sö). loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves, to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea, the enchantress, 15 15. Circe (sür’së) of Aeaea e’e-). desired me, and detained me in her hail. But in my heart I never gave consent. Where shall a man find sweetness to surpass his OWfl home and his parents? In far lands he shall not, though he find a house of gold. -

The Odyssey Homer Translated by Robert Fitzgerald

The Wanderings of Odysseus from The Odyssey Homer Translated by Robert Fitzgerald Book Nine: new Coasts and poseidon’s son ―What shall I say first? What shall I keep until the end? What conflict is introduced in Odysseus’ initial statements at the banquet? The gods have tried1 me in a thousands ways. What do these statements indicate about the kind of journey he has had? But first my name: Let that be known to you, 5 and if I pull away from pitiless death, friendship will bind us, though my land lies far. Now this was the reply Odysseus made: . ―I am Laertes‘ son, Odysseus. How are Odysseus’ comments about himself during his speech at Men hold2 me Alcinous’ banquet appropriate for an epic hero? formidable for guile in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky‘s rim. 10 My home is on the peaked seamark of Ithaca under Mount Neion‘s windblown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Doulikhion, Same, wooded Zakynthos—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, 15 and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy‘s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, Odysseus refers to two beautiful goddesses, Calypso and Circe, who have though I have been detained long by Calypso, delayed him on their islands. (Details about Circe appear in Book 10.) loveliest among goddesses, who held me Notice, however, that Odysseus seems nostalgic for his own family and 20 in her smooth caves, to be her heart‘s delight, homeland. -

Myths and Legends: Odysseus and His Odyssey, the Short Version by Caroline H

Myths and Legends: Odysseus and his odyssey, the short version By Caroline H. Harding and Samuel B. Harding, adapted by Newsela staff on 01.10.17 Word Count 1,415 Level 1030L Escaping from the island of the Cyclopes — one-eyed, ill-tempered giants — the hero Odysseus calls back to the shore, taunting the Cyclops Polyphemus, who heaves a boulder at the ship. Painting by Arnold Böcklin in 1896. SECOND: A drawing of a cyclops, courtesy of CSA Images/B&W Engrave Ink Collection and Getty Images. Greek mythology began thousands of years ago because there was a need to explain natural events, disasters, and events in history. Myths were created about gods and goddesses who had supernatural powers, human feelings and looked human. These ideas were passed down in beliefs and stories. The following stories are about Odysseus, the son of the king of the Greek island of Ithaca and a hero, who was described to be as wise as Zeus, king of the gods. For 10 years, the Greek army battled the Trojans in the walled city of Troy, but could not get over, under or through the walls that protected it. Finally, Odysseus came up with the idea of a large hollow, wooden horse, that would be filled with Greek soldiers. The people of Troy woke one morning and found that no army surrounded the city, so they thought the enemy had returned to their ships and were finally sailing back to Greece. A great horse had been left This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. -

The Myth of Helen of Troy: Reinterpreting the Archetypes of the Myth in Solo and Collaborative Forms of Playwriting

The Myth of Helen of Troy: Reinterpreting the Archetypes of the Myth in Solo and Collaborative Forms of Playwriting. Volume One of Two Submitted by Ioannis Souris to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Practice In October 2011 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 1 Abstract In this practice-based thesis I examine how I interpreted the myth of Helen of Troy in solo and collaborative forms of playwriting. For the interpretation of Helen’s myth in solo playwriting, I wrote a script that contextualised in a contemporary world the most significant characters of Helen’s myth which are: Helen, Menelaus, Hermione, Paris, Hecuba, Priam. This first practical research project investigated how characters that were contemporary reconstructions of Menelaus, Hermione, Paris , Hecuba, Priam, Telemachus were affected by Helen as an absent figure, a figure that was not present on stage but was remembered and discussed by characters. For the interpretation of Helen’s myth in collaborative playwriting, I asked three female performers to analyse the character of Helen and then conceptualise and write their own Helen character. The performers’ analyses and rewritings of Helen inspired me to write a script whose story evolved around three Helen characters that were dead and interacted with one another in a space of death. -

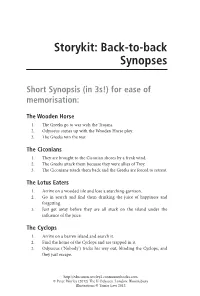

Back-To-Back Synopses.Indd

Storykit: Back-to-back Synopses Short Synopsis (in 3s!) for ease of memorisation: The Wooden Horse 1. The Greeks go to war with the Trojans. 2. Odysseus comes up with the Wooden Horse ploy. 3. The Greeks win the war. The Ciconians 1. They are brought to the Ciconian shores by a freak wind. 2. The Greeks attack them because they were allies of Troy. 3. The Ciconians attack them back and the Greeks are forced to retreat. The Lotus Eaters 1. Arrive on a wooded isle and lose a searching-garrison. 2. Go in search and find them drinking the juice of happiness and forgetting. 3. Just get away before they are all stuck on the island under the influence of the juice. The Cyclops 1. Arrive on a barren island and search it. 2. Find the home of the Cyclops and are trapped in it. 3. Odysseus (‘Nobody’) tricks his way out, blinding the Cyclops, and they just escape. http://education.worley2.continuumbooks.com © Peter Worley (2012) The If Odyseey. London: Bloomsbury Illustrations © Tamar Levi 2012 Aeolus 1. Arrive on a fortified island and are finally welcomed as guests. 2. Odysseus is given a bag as a gift by Aeolus. 3. Crew mutiny just as they reach home and release the winds from inside the bag, blowing them back out to sea. The Laestrygonians 1. Arrive on another island with an encircled harbour. 2. Find out the hard way that this is an island of giant cannibals. 3. They only just escaped with their lives. Circe 1. Arrive on yet another island only for some of the men to be turned into pigs by the goddess Circe. -

Story 1: the Cicones

THE WANDERINGS OF ODYSSEUS – STORIES 1-11 STORY 1: THE CICONES THE WANDERINGS OF ODYSSEUS – STORIES 1-11 (OF 30) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 THE CICONES SHIP AND CREW COUNT BEFORE AFTER 12 Ships 12 Ships 608 Men 536 Men After ten long years, the Trojan War is over. The ACHAEANS (a name for the Greeks) have defeated the Trojans. ODYSSEUS, his men, and their twelve ships, begin their journey home to ITHACA. The storm winds take them to the land of the CICONES where Odysseus and his men sack the main city Ismarus, attack their people, and steal their possessions. Odysseus and each of his men share the stolen riches equally. Odysseus urges that they leave. The crew do not listen. They slaughter the Cicones’ sheep and cattle, and drink their wine. The Cicones call for help. Now stronger and larger in number, the Cicones fight back with force. Odysseus loses six men from each of his twelve ships. He feels he and his men are being punished by ZEUS. Odysseus and the rest of his crew sail away before any more men are killed. BOOK AND LINE REFERENCES BOOK 9 (OF 24) Fagles (Fa) Fitzgerald (Fi) Lattimore (La) Lombardo (Lo) 9.44-75 9.43-73 9.39-66 9.42-68 NOTE: The numbers appearing after the Book Number (in this case, Book 9) are the specific line numbers for each translation. Although Book Numbers are the same across all four translations, line numbers are not. If you are using a prose translation (and line numbers aren’t provided), use the Book references provided above; the line numbers can be used to provide an approximate location in that Book for the particular passages. -

Mythology, Greek, Roman Allusions

Advanced Placement Tool Box Mythological Allusions –Classical (Greek), Roman, Norse – a short reference • Achilles –the greatest warrior on the Greek side in the Trojan war whose mother tried to make immortal when as an infant she bathed him in magical river, but the heel by which she held him remained vulnerable. • Adonis –an extremely beautiful boy who was loved by Aphrodite, the goddess of love. By extension, an “Adonis” is any handsome young man. • Aeneas –a famous warrior, a leader in the Trojan War on the Trojan side; hero of the Aeneid by Virgil. Because he carried his elderly father out of the ruined city of Troy on his back, Aeneas represents filial devotion and duty. The doomed love of Aeneas and Dido has been a source for artistic creation since ancient times. • Aeolus –god of the winds, ruler of a floating island, who extends hospitality to Odysseus on his long trip home • Agamemnon –The king who led the Greeks against Troy. To gain favorable wind for the Greek sailing fleet to Troy, he sacrificed his daughter Iphigenia to the goddess Artemis, and so came under a curse. After he returned home victorious, he was murdered by his wife Clytemnestra, and her lover, Aegisthus. • Ajax –a Greek warrior in the Trojan War who is described as being of colossal stature, second only to Achilles in courage and strength. He was however slow witted and excessively proud. • Amazons –a nation of warrior women. The Amazons burned off their right breasts so that they could use a bow and arrow more efficiently in war. -

Virgil, Priest of Apollo?

The Classical Review http://journals.cambridge.org/CAR Additional services for The Classical Review: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Virgil, Priest of Apollo? W. Warde Fowler The Classical Review / Volume 27 / Issue 03 / May 1913, pp 85 - 87 DOI: 10.1017/S0009840X00004790, Published online: 27 October 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0009840X00004790 How to cite this article: W. Warde Fowler (1913). Virgil, Priest of Apollo?. The Classical Review, 27, pp 85-87 doi:10.1017/S0009840X00004790 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/CAR, IP address: 130.216.129.208 on 10 Apr 2015 THE CLASSICAL REVIEW VIRGIL, PRIEST OF APOLLO ? NOTES ON MR. RAPER'S RECENT Thrace. But in the story of these three, PAPER. as we have it in Ovid, there is hardly a mention of Thrace, and the scene is not MY old friend Mr. Raper will, I know, laid there. Then in Georg. 2. 37, forgive me for these notes. Let me Virgil ' shows wild joy at the thought assure him that he gave me excellent of re-arraying his ancestral Ismarian employment during one of the many mountain-sides with the glory of the wet days of last February. He took vine': ' iuvat Ismara Baccho Conserere ' me through a number of passages, none . but go on, and you read ' atque the less delightful for being familiar: olea magnum vestire Taburnum.' Now and what better occupation can a man Taburnus was not in Thrace, but in have than the leisurely contemplation Campania, and if Virgil loved Thrace, of old friends' faces, even if he be unable he loved Campania at least as much. -

Greek Tragedy and the Epic Cycle: Narrative Tradition, Texts, Fragments

GREEK TRAGEDY AND THE EPIC CYCLE: NARRATIVE TRADITION, TEXTS, FRAGMENTS By Daniel Dooley A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland October 2017 © Daniel Dooley All Rights Reserved Abstract This dissertation analyzes the pervasive influence of the Epic Cycle, a set of Greek poems that sought collectively to narrate all the major events of the Trojan War, upon Greek tragedy, primarily those tragedies that were produced in the fifth century B.C. This influence is most clearly discernible in the high proportion of tragedies by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides that tell stories relating to the Trojan War and do so in ways that reveal the tragedians’ engagement with non-Homeric epic. An introduction lays out the sources, argues that the earlier literary tradition in the form of specific texts played a major role in shaping the compositions of the tragedians, and distinguishes the nature of the relationship between tragedy and the Epic Cycle from the ways in which tragedy made use of the Homeric epics. There follow three chapters each dedicated to a different poem of the Trojan Cycle: the Cypria, which communicated to Euripides and others the cosmic origins of the war and offered the greatest variety of episodes; the Little Iliad, which highlighted Odysseus’ career as a military strategist and found special favor with Sophocles; and the Telegony, which completed the Cycle by describing the peculiar circumstances of Odysseus’ death, attributed to an even more bizarre cause in preserved verses by Aeschylus. These case studies are taken to be representative of Greek tragedy’s reception of the Epic Cycle as a whole; while the other Trojan epics (the Aethiopis, Iliupersis, and Nostoi) are not treated comprehensively, they enter into the discussion at various points. -

Validation of Aeolus Wind Products Above the Atlantic Ocean

https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-2020-198 Preprint. Discussion started: 25 May 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. Validation of Aeolus wind products above the Atlantic Ocean Holger Baars1, Alina Herzog1,2,3, Birgit Heese1, Kevin Ohneiser1,2, Karsten Hanbuch1, Julian Hofer1, Zhenping Yin1,4,5, Ronny Engelmann1, and Ulla Wandinger1 1Leibniz Institute for Tropospheric Research (TROPOS), Leipzig, Germany 2Institute for Meteorology, Universität Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany 3now at: LEM-Software, Ingenieurbüro für Last- und Energiemanagement, Leipzig, Germany 4School of Electronic Information, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China 5Key Laboratory of Geospace Environment and Geodesy, Ministry of Education, Wuhan, China Correspondence: Holger Baars ([email protected]) Abstract. In August 2018, the first Doppler wind lidar in space called ALADIN was launched on-board the satellite Aeolus by the European Space Agency ESA. Aeolus measures horizontal wind profiles in the troposphere and lower stratosphere on a global basis. Furthermore, profiles of aerosol and cloud properties can be retrieved via the high-spectral-resolution lidar (HSRL) technique. The Aeolus mission is supposed to improve the quality of weather forecasts and the understanding of 5 atmospheric processes. We used the chance of opportunity to perform a unique validation of the wind products of Aeolus by utilizing the RV Po- larstern cruise PS116 from Bremerhaven to Cape Town in November/December 2018. Due to concerted course modifications, six direct intersections with the Aeolus ground track could be achieved on the Atlantic Ocean, west of the African continent. For the validation of the Aeolus wind products, we launched additional radiosondes and used the EARLINET/ACTRIS lidar 10 PollyXT for atmospheric scene analysis. -

Representing Difference in Odyssey 9 Traditional Colonial Readings Of

Representing Difference in Odyssey 9 Traditional colonial readings of Book 9 of the Odyssey (Most 1989, Pucci 1997, Dougherty 1991) interpret the Cyclops episode as polarizing: the Ithacans appear to be civilized colonizers, and Polyphemus appears to be an uncivilized and inhospitable host. My paper builds on Rinon’s criticism of this polarity (2007). It uses the difference between narrating and experiencing focalizations (de Jong 1992) to show the limits of these colonial readings. Although Odysseus’ narrating focalization (his retrospective narration) does encourage his audience to see the Cyclops as Other, details of his experiencing focalization (his eye-witness, in-the-moment narration) identify similarities between himself and the Other. So, instead of a strictly polar colonial relationship, Odysseus’ experiencing focalization supports the postcolonial idea of hybridity in the Mediterranean, or what Malkin calls the ‘middle ground’ of overlapping cultures (2004). My paper also accomplishes this reading by combining de Jong’s structuralist narratology (2001) with Allan’s recent work on narrative immersion (2020). In section 1, I analyze Odysseus’s introduction at the beginning of the Cyclops episode (9.106-142). As Scodel (2005) notes, this section is distinct from the rest of the narrative in chronology and focalization, since Odysseus’ description of the Cyclopes (whom he has not encountered yet) is necessarily retrospective. Here Odysseus introduces the Cyclopes as lawless and outrageous, and as Pucci (1997) and Dougherty (1991) argue, he establishes a colonial relationship between the Ithacans, who settle the neighboring Island of the Goats, and the Cyclopes, who seem incapable of just that (9.116-142).