Arles and Marseille)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Réseau Départemental Des Transports Des Bouches-Du-Rhône Réseau

57 Réseau départemental des transports plus de CG13 57 moins de CO2 des Bouches-du-Rhône 57 59 59 Ecopôle DIRECTION DES TRANSPORTS ET DES PORTS / JANVIER 2012 ET DES PORTS DIRECTION DES TRANSPORTS 17 240 ZA La M1 Valentine La Fourragère 240 Euroméditerranée 240 Arenc T2 allôcartreize Athélia Zone d’Activités d’industrie et de commerce 0810001326 Numéro Azur - prix d’un appel local Navettes rapides Lignes interurbaines départementales Points de vente N° Lignes organisées par le Conseil Général des Bouches-du-Rhône Exploitants Téléphone du réseau Cartreize 6 Saint Chamas - Salon-de-Provence par Grans TRANSAZUR 04 90 53 71 11 ● Gare Routière de Marseille St Charles 11 La Bouilladisse - Aix-en-Provence par La Destrousse - Peypin - Cadolive - Gréasque Fuveau TELLESCHI 04 42 28 40 22 Pôle d’Echanges St Charles - Rue Honnorat 12 Meyreuil - Aix-en-Provence par Gardanne Autocars BLANC - 13003 Marseille - Tél.: 04 91 08 16 40 15 Berre l’Etang - Aix-en-Provence par Rognac et Velaux SUMA 04 42 87 05 84 ACCUEIL-INFO BILLETTERIE DÉPARTEMENTALE : Du lundi au samedi de 6h à 20h / Le dimanche et les jours fériés (sauf le 25 décembre, 16 Lançon de Provence - Aix-en-Provence par La Fare Les Oliviers SUMA 04 42 87 05 84 le 1er janvier et le 1er mai) de 7h30 à 12h30 et de 13h30 à 18h30 17 Salon-de-Provence - Aéroport Marseille Provence par Lançon - Rognac - Vitrolles SUMA 04 42 87 05 84 Navette Aéroport Tous les jours de 5h30 à 21h30 18 Arles - Aix-en-Provence par Raphèle les Arles - St Martin de Crau - Salon-de-Provence TELLESCHI 04 42 28 40 22 ● Envia &Vous -

Canal Du Midi’ Guide Highlights the Local Attractions and Hidden Gems of the Famous French Waterway

LE BOAT’S COLORFUL NEW ‘CANAL DU MIDI’ GUIDE HIGHLIGHTS THE LOCAL ATTRACTIONS AND HIDDEN GEMS OF THE FAMOUS FRENCH WATERWAY Comprehensive, 100-Page Brochure Details Cultural, Culinary, Sports and Family Attractions Along Famous Route Clearwater, FL (October 26, 2016) – Le Boat, Europe’s largest self-drive boating company, announced the availability of its new “Canal Du Midi” guide, a comprehensive, 100-page brochure that offers information on the waterside attractions, restaurants, local markets, and vineyards of one of the world’s most popular destinations and celebrated wine region. The guide is free and available for download from the Le Boat website at http://bit.ly/2dTA5rY. From the Ventenac wine cave at Château Ventenac to the captivating, hilltop medieval walled city of Carcassonne, every page in the new Canal du Midi guide is packed with fascinating regional history, practical advice and insider’s tips on getting the most of a Le Boat self-drive vacation. “Whether you’re a lover of great food and fine wine, a history and culture enthusiast, a small group or family, the Guide is your ultimate resource for exploring this delightful, sun- drenched region of Southern France,” said Shannan Brennan, Le Boat’s head of Distribution and Marketing, U.S., Canada and Latin America. “The Guide contains easy-to-follow maps and suggested itineraries, local tours to get the most out of your visit, recommendations on the best places to moor, gourmet restaurants, vineyards – and much more.” Days of Wine and Rosé – and 10% Off Canal du Midi leisurely winds its way through the Languedoc-Roussillon region of France. -

Download Trip Notes

PROVENCE & THE FRENCH RIVIERA Blue-Roads | Europe Glamour, picturesque villages and stunning mountain scenery: this tour through the French Riviera and Provence is sure to impress with its diversity and dramatic beauty! Join us as we experience the luxury of the French Riviera, marvel at the architecture of Avignon and venture into the mighty Gorges du Verdon - soaking up some fascinating history along the way. TOUR CODE: BEHPFNN-2 Thank You for Choosing Blue-Roads Thank you for choosing to travel with Back-Roads Touring. We can’t wait for you to join us on the mini-coach! About Your Tour Notes THE BLUE-ROADS DIFFERENCE Enjoy a picnic lunch and taste delicious produce at an olive farm in These tour notes contain everything you need to know Les-Baux-de-Provence before your tour departs – including where to meet, Marvel at the extraordinary Gorges du what to bring with you and what you can expect to do Verdon: the 'Grand Canyon of Europe' on each day of your itinerary. You can also print this Experience the mesmerising Carrières document out, use it as a checklist and bring it with you de Lumières multimedia art show in on tour. Les Baux-de-Provence Please Note: We recommend that you refresh TOUR CURRENCIES this document one week before your tour departs to ensure you have the most up-to-date + France - EUR accommodation list and itinerary information available. Your Itinerary DAY 1 | NICE Meet the group in the shining capital of the French Riviera and get to know one another over a delicious welcome meal. -

SOUTHERN FRANCE: LANGUEDOC & PROVENCE October 2-14, 2017

SOUTHERN FRANCE: LANGUEDOC & PROVENCE October 2-14, 2017 13 days from $4,496 total price from Boston, New York ($3,795 air & land inclusive plus $701 airline taxes and fees) This tour is provided by Odysseys Unlimited, six-time honoree Travel & Leisure’s World’s Best Tour Operators award. An Exclusive Small Group Tour for Alumnae/i & Friends of Bryn Mawr College Featuring Catherine Lafarge, Professor Emeritus of French Dear Bryn Mawr Alumnae/i, Family and Friends, We invite you to join us on a special 13-day journey to Southern France. This exclusive tour features Southern France’s highlights from the Pyrénées and Languedoc, to beloved Provence. We begin in the beautiful town of Sorèze, and explore the historic market town of Albi, including a visit to the Toulouse-Lautrec Museum. We then set off through the Pyrénées, before traveling along the Catalan coast to Collioure, France. Next, we take a half-day cruise on the Canal du Midi, a UNESCO site, and journey to Avignon, where we explore the beautiful Saint-Bénézet Bridge and the Palais des Papes. We conclude our journey exploring the beautiful cities and vil- lages of Aix-en-Provence, Roussillon, and Gordes. Space on this exclusive, air-inclusive tour for Bryn Mawr is limited to just 24 guests, and will be accompanied by Professor Emeritus Catherine Lafarge. We anticipate that space will fill quickly; your early reservations are encouraged. Warm regards, Saskia Subramanian ’88 President, Bryn Mawr College Alumnae Association BRYN MAWR ASSOCIATION RESERVATION FORM — SOUTHERN FRANCE: LANGUEDOC & PROVENCE Enclosed is my/our deposit for $______($500 per person) for ____ person/people on Southern France: Languedoc & Provence departing October 2, 2017. -

Of Council Regulation (EEC) No 2081/92 on the Protection of Geographical Indications and Designations of Origin

C 201/6 EN Official Journal of the European Communities 27.6.98 Publication of an application for registration pursuant to Article 6(2) of Council Regulation (EEC) No 2081/92 on the protection of geographical indications and designations of origin (98/C 201/04) This publication confers the right to object to the application pursuant to Article 7 of the abovementioned Regulation. Any objection to this application must be submitted via the competent authority in the Member State concerned within a time limit of six months from the date of this publication. The arguments for publication are set out below, in particular under 4.6, and are considered to justify the application within the meaning of Regulation (EEC) No 2081/92. COUNCIL REGULATION (EEC) No 2081/92 APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION: ARTICLE 5 PDO (x)ÚÚPGI (Ú) National application No: — 1. Responsible department in the Member State: Name: Institut national des appellations d’origine (National Institute for Designations of Origin) Address:Ù138, Champs-^lys~es — F-75008 Paris Tel: (33-1) 53Ø89Ø80Ø00 Fax: (33-1) 42Ø25Ø57Ø97 2. Applicant group: 2.1.ÙName: Vall~e des Baux Olive Tree Inter-trade Association 2.2.ÙAddress:ÙMairie de Maussane-les-Alpilles — F-13520 Maussane-les-Alpilles 2.3.ÙComposition: producer/processor (x)ÚÚother (Ú) 3. Type of product: Class 1.6 — Fruits — Olives 4. Specification: (summary of requirements under Article 4(2)): 4.1. Name: Olives cass~es de la Vall~e des Baux de Provence. 4.2. Description: Olives cass~es de la Vall~e des Baux de Provence come exclusively from the Salonenque or B~ruguette varieties. -

Comment Franchir Les Montagnes Des Pyrénées Le Plus Aisément Possible

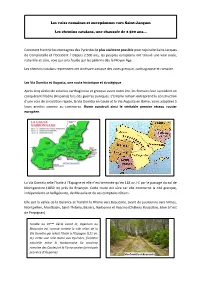

Les voies romaines et européennes vers Saint-Jacques Les chemins catalans, une chaussée de 2 500 ans… Comment franchir les montagnes des Pyrénées le plus aisément possible pour rejoindre Saint-Jacques de Compostelle et l’Occident ? Depuis 2 500 ans, les peuples européens ont trouvé une voie aisée, naturelle et sûre, voie qui sera foulée par les pèlerins dès le Moyen Âge… Les chemins catalans reprennent cet itinéraire antique des voies grecque, carthaginoise et romaine. Les Via Domitia et Augusta, une route historique et stratégique Après cinq siècles de colonies carthaginoise et grecque avant notre ère, les Romains leur succèdent en conquérant l’Ibérie (Hispanie) lors des guerres puniques. L’Empire romain entreprend la construction d’une voie de circulation rapide, la Via Domitia en Gaule et la Via Augusta en Ibérie, voies adaptées à leurs armées comme au commerce. Rome construit ainsi le véritable premier réseau routier européen. La Via Domitia relie l’Italie à l’Espagne et elle n’est terminée qu’en 118 av J-C par le passage du col de Montgenèvre (1850 m) près de Briançon. Cette route est sûre car elle contourne la cité grecque, indépendante et belligérante, de Massalia et de ses comptoirs côtiers. Elle suit la vallée de la Durance et franchit le Rhône vers Beaucaire, avant de poursuivre vers Nîmes, Montpellier, Montbazin, Saint-Thibéry, Béziers, Narbonne et Ruscino (Château Roussillon, 6 km à l’est de Perpignan). Fondée au VIIème siècle avant JC, Ugernum ou Beaucaire est connue comme la ville relais de la Via Domitia qui reliait l’Italie à l’Espagne (121 av. -

Ancient Rome and Early Christianity, 500 B.C.-A.D

CHAPTER 6 • OBJECTIVE Ancient Rome and Early Trace the rise and fall of the Roman Empire, and analyze its impact on Christianity, 500 B.C.-A.D. 500 culture, government, and religion. Previewing Main Ideas Previewing Main Ideas Urge students to look for connections POWER AND AUTHORITY Rome began as a republic, a government in which elected officials represent the people. Eventually, absolute rulers between the three main ideas. For exam- called emperors seized power and expanded the empire. ple, point out that Rome’s rise to an Geography About how many miles did the Roman Empire stretch empire led to the spread of Christianity. from east to west? Emphasize the universality of human EMPIRE BUILDING At its height, the Roman Empire touched three desires for power and authority, as well continents—Europe, Asia, and Africa. For several centuries, Rome brought as for a spiritual connection. peace and prosperity to its empire before its eventual collapse. Geography Why was the Mediterranean Sea important to the Roman Empire? Accessing Prior Knowledge RELIGIOUS AND ETHICAL SYSTEMS Out of Judea rose a monotheistic, Ask students to list any ancient Romans or single-god, religion known as Christianity. Based on the teachings of that they can name (Possible Answers: Jesus of Nazareth, it soon spread throughout Rome and beyond. Julius Caesar, Mark Antony) and discuss Geography What geographic features might have helped or hindered the what they already know about them. spread of Christianity throughout the Roman Empire? Invite students to share their knowledge of early Christianity and Judaism. Tell them that Christianity comes from the INTERNET RESOURCES Greek word christos, meaning “messiah” • Interactive Maps Go to classzone.com for: or “savior.” • Interactive Visuals • Research Links • Maps • Interactive Primary Sources • Internet Activities • Test Practice Geography Answers • Primary Sources • Current Events • Chapter Quiz POWER AND AUTHORITY The Roman Empire stretched about 3,500 miles from east to west. -

Hidden Treasures of Southern France May 5 - 14, 2011

Hidden Treasures of Southern France May 5 - 14, 2011 Thursday, May 5th. Departure from your chosen gateway city. Overnight: Plane Friday, May 6th. Your arrival in Toulouse will be met by your Discover Europe Tour Director and your coach, before heading directly to your hotel. After time to unpack, rest, and settle in, Smith Faculty Speaker, Pamela Petro, will introduce the week ahead. The day will conclude with a welcome dinner. (D) Overnight: Toulouse Saturday, May 7th. This morning you’ll visit the premier fortified city in Europe, Carcassonne, a UNESCOWorld Heritage site. This spectacular medieval stronghold, replete with towers and turreted walls, first became a fortress under the Celts in th6 century BC. You’ll then return to Toulouse for a free afternoon of shopping and sightseeing—options include St Sernin, one of the most influential Romanesque abbeys in Europe—in this vibrant, Mediterranean-influenced city. In the evening you may sample a local restaurant of your choice. (B) Overnight: Toulouse Sunday, May 8th. Leaving Toulouse, your first stop today will be Albi, a classic red brick-and-tile Languedoc town where Cathars, 12th century Catholic heretics, were infamously burned at the stake. In Albi you’ll visit the Musee Toulouse- Lautrec and one of the most startlingly original cathedrals of the Middle Ages. Afterwards you’ll stop in Rodez for lunch and visit to the Musee Fenaille, with its fabulous, utterly unique collection of figurative menhirs. You’ll continue on to your hotel just outside the ancient pilgrimage destination of Rocamadour. (B, D) Overnight: Rocamadour Monday, May 9th. -

Le Réseau Viaire Antique Du Tricastin Et De La Valdaine : Relecture Des Travaux Anciens Et Données Nouvelles Cécile Jung

Le réseau viaire antique du Tricastin et de la Valdaine : relecture des travaux anciens et données nouvelles Cécile Jung To cite this version: Cécile Jung. Le réseau viaire antique du Tricastin et de la Valdaine : relecture des travaux anciens et données nouvelles. Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise, Presse universitaire de la Méditerranée, 2009, pp.85-113. hal-00598526 HAL Id: hal-00598526 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00598526 Submitted on 7 Jun 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Le réseau viaire antique du Tricastin et de la Valdaine : relecture des travaux anciens et données nouvelles Cécile JUNG Résumé: À partir de travaux de carto-interprétation, de sondages archéologiques et de collectes de travaux anciens, le tracé de la voie d’Agrippa entre Montélimar et Orange est ici repris et discuté. Par ailleurs, l’analyse des documents planimétriques (cartes anciennes et photographies aériennes) et les résultats de plusieurs opérations archéologiques permettent de proposer un réseau de chemins probablement actifs dès l’Antiquité. Mots-clés: voie d’Agrippa, vallée du Rhône, analyse cartographique, centuriation B d’Orange, itinéraires antiques. Abstract: The layout of the Via Agrippa, between Montélimar and Orange, is studied and discussed in this article. -

Geddie 1 the USE of OCCITAN DIALECTS in LANGUEDOC

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Mississippi Geddie 1 THE USE OF OCCITAN DIALECTS IN LANGUEDOC-ROUSSILLON, FRANCE By Virginia Jane Geddie A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Oxford May 2014 Approved by _______________________________ Advisor: Professor Allison Burkette _______________________________ Reader: Professor Felice Coles _______________________________ Reader: Professor Robert Barnard Geddie 1 Abstract Since the medieval period, the Occitan dialects of southern France have been a significant part of the culture of the Midi region of France. In the past, it was the language of the state and literature. However, Occitan dialects have been in a slow decline, beginning with the Ordinance of Villers-Coterêts in 1539 which banned the use of Occitan in state affairs. While this did little to affect the daily life and usage of Occitan, it established a precedent that is still referred to in modern arguments about the use of regional languages (Costa, 2). In the beginning of the 21st century, the position of Occitan dialects in Midi is precarious. This thesis will investigate the current use of Occitan dialects in and around Montpellier, France, particularly which dialects are most commonly used in the region of Languedoc-Roussillon (where Montpellier is located), the environment in which they are learned, the methods of transmission, and the general attitude towards Occitan. It will also discuss Occitan’s current use in literature, music, and politics. While the primary geographic focus of this thesis will be on Montpellier and its surroundings, it should somewhat applicable to the whole of Occitan speaking France. -

The World's Measure: Caesar's Geographies of Gallia and Britannia in Their Contexts and As Evidence of His World Map

The World's Measure: Caesar's Geographies of Gallia and Britannia in their Contexts and as Evidence of his World Map Christopher B. Krebs American Journal of Philology, Volume 139, Number 1 (Whole Number 553), Spring 2018, pp. 93-122 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/ajp.2018.0003 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/687618 Access provided at 25 Oct 2019 22:25 GMT from Stanford Libraries THE WORLD’S MEASURE: CAESAR’S GEOGRAPHIES OF GALLIA AND BRITANNIA IN THEIR CONTEXTS AND AS EVIDENCE OF HIS WORLD MAP CHRISTOPHER B. KREBS u Abstract: Caesar’s geographies of Gallia and Britannia as set out in the Bellum Gallicum differ in kind, the former being “descriptive” and much indebted to the techniques of Roman land surveying, the latter being “scientific” and informed by the methods of Greek geographers. This difference results from their different contexts: here imperialist, there “cartographic.” The geography of Britannia is ultimately part of Caesar’s (only passingly and late) attested great cartographic endeavor to measure “the world,” the beginning of which coincided with his second British expedition. To Tony Woodman, on the occasion of his retirement as Basil L. Gildersleeve Professor of Classics at the University of Virginia, in gratitude. IN ALEXANDRIA AT DINNER with Cleopatra, Caesar felt the sting of curiosity. He inquired of “the linen-wearing Acoreus” (linigerum . Acorea, Luc. 10.175), a learned priest of Isis, whether he would illuminate him on the lands and peoples, gods and customs of Egypt. Surely, Lucan has him add, there had never been “a visitor more capable of the world” than he (mundique capacior hospes, 10.183). -

Orbis Terrarum DATE: AD 20 AUTHOR: Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa

Orbis Terrarum #118 TITLE: Orbis Terrarum DATE: A.D. 20 AUTHOR: Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa DESCRIPTION: The profound difference between the Roman and the Greek mind is illustrated with peculiar clarity in their maps. The Romans were indifferent to mathematical geography, with its system of latitudes and longitudes, its astronomical measurements, and its problem of projections. What they wanted was a practical map to be used for military and administrative purposes. Disregarding the elaborate projections of the Greeks, they reverted to the old disk map of the Ionian geographers as being better adapted to their purposes. Within this round frame the Roman cartographers placed the Orbis Terrarum, the circuit of the world. There are only scanty records of Roman maps of the Republic. The earliest of which we hear, the Sardinia map of 174 B.C., clearly had a strong pictorial element. But there is some evidence that, as we should expect from a land-based and, at that time, well advanced agricultural people, subsequent mapping development before Julius Caesar was dominated by land survey; the earliest recorded Roman survey map is as early as 167-164 B.C. If land survey did play such an important part, then these plans, being based on centuriation requirements and therefore square or rectangular, may have influenced the shape of smaller-scale maps. This shape was also one that suited the Roman habit of placing a large map on a wall of a temple or colonnade. Varro (116-27 B.C.) in his De re rustica, published in 37 B.C., introduces the speakers meeting at the temple of Mother Earth [Tellus] as they look at Italiam pictam [Italy painted].