Theory of Knowledge in Britain from 1860 to 1950

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Augustine on Knowledge

Augustine on Knowledge Divine Illumination as an Argument Against Scepticism ANITA VAN DER BOS RMA: RELIGION & CULTURE Rijksuniversiteit Groningen Research Master Thesis s2217473, April 2017 FIRST SUPERVISOR: dr. M. Van Dijk SECOND SUPERVISOR: dr. dr. F.L. Roig Lanzillotta 1 2 Content Augustine on Knowledge ........................................................................................................................ 1 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ 4 Preface .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 7 The life of Saint Augustine ................................................................................................................... 9 The influence of the Contra Academicos .......................................................................................... 13 Note on the quotations ........................................................................................................................ 14 1. Scepticism ........................................................................................................................................ -

Kant's Theory of Knowledge and Hegel's Criticism

U.Ü. FEN-EDEBİYAT FAKÜLTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER DERGİSİ Yıl: 2, Sayı: 2, 2000-2001 KANT’S THEORY OF KNOWLEDGE AND HEGEL’S CRITICISM A. Kadir ÇÜÇEN* ABSTRACT Kant inquires into the possibility, sources, conditions and limits of knowledge in the tradition of modern philosophy. Before knowing God, being and reality, Kant, who aims to question what knowledge is, explains the content of pure reason. He formalates a theory of knowledge but his theory is neither a rationalist nor an empiricist theory of knowledge. He investigates the structure of knowledge, the possible conditions of experience and a priori concepts and categories of pure reason; so he makes a revolution like that of Copernicus . Hegel, who is one of proponents of the German idealism, criticizes the Kantian theory of knowledge for “wanting to know before one knows”. For Hegel, Kant’s a priori concepts and categories are meaningless and empty. He claims that the unity of subject and object has been explained in that of the “Absolute”. Therefore, the theory of knowledge goes beyond the dogmatism of the “thing-in- itself” and the foundations of mathematics and natural sciences; and reaches the domain of absolute knowledge. Hegel’s criticism of Kantian theory of knowledge opens new possibilities for the theory of knowledge in our age. ÖZET Kant’ın Bilgi Kuramı ve Hegel’in Eleştirisi Modern felsefe geleneği çerçevesinde Kant, bilginin imkânını, kaynağını, kapsamını ve ölçütlerini ele alarak, doğru bilginin sınırlarını irdelemiştir. Tanrı’yı, varlığı ve gerçekliği bilmeden önce, bilginin neliğini sorgulamayı kendine amaç edinen Kant, saf aklın içeriğini incelemiştir. Saf aklın a priori kavram ve kategorilerini, deneyin görüsünü ve bilgi yapısını veren, fakat ne usçu ne de deneyci * Uludag University, Faculty of Sciences and Letters, Dept. -

Hegel and the Metaphysical Frontiers of Political Theory

Copyrighted material - provided by Taylor & Francis Eric Goodfield. American University Beirut. 23/09/2014 Hegel and the Metaphysical Frontiers of Political Theory For over 150 years G.W.F. Hegel’s ghost has haunted theoretical understanding and practice. His opponents first, and later his defenders, have equally defined their programs against and with his. In this way Hegel’s political thought has both situated and displaced modern political theorizing. This book takes the reception of Hegel’s political thought as a lens through which contemporary methodological and ideological prerogatives are exposed. It traces the nineteenth- century origins of the positivist revolt against Hegel’s legacy forward to political science’s turn away from philosophical tradition in the twentieth century. The book critically reviews the subsequent revisionist trend that has eliminated his metaphysics from contemporary considerations of his political thought. It then moves to re- evaluate their relation and defend their inseparability in his major work on politics: the Philosophy of Right. Against this background, the book concludes with an argument for the inherent meta- physical dimension of political theorizing itself. Goodfield takes Hegel’s recep- tion, representation, as well as rejection in Anglo-American scholarship as a mirror in which its metaphysical presuppositions of the political are exception- ally well reflected. It is through such reflection, he argues, that we may begin to come to terms with them. This book will be of great interest to students, scholars, and readers of polit- ical theory and philosophy, Hegel, metaphysics and the philosophy of the social sciences. Eric Lee Goodfield is Visiting Assistant Professor at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon. -

History of Philosophy Outlines from Wheaton College (IL)

Property of Wheaton College. HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY 311 Arthur F. Holmes Office: Blanch ard E4 83 Fall, 1992 Ext. 5887 Texts W. Kaufman, Philosophical Classics (Prentice-Hall, 2nd ed., 1968) Vol. I Thales to Occam Vol. II Bacon to Kant S. Stumpf, Socrates to Sartre (McGraW Hill, 3rd ed., 1982, or 4th ed., 1988) For further reading see: F. Copleston, A History of Philosophy. A multi-volume set in the library, also in paperback in the bookstore. W. K. C. Guthrie, A History of Greek Philosophy Diogenes Allen, Philosophy for Understanding Theology A. H. Armstrong & R. A. Markus, Christian Faith and Greek Philosophy A. H. Armstrong (ed.), Cambridge History of Later Greek and Early Medieval Philosophy Encyclopedia of Philosophy Objectives 1. To survey the history of Western philosophy with emphasis on major men and problems, developing themes and traditions and the influence of Christianity. 2. To uncover historical connections betWeen philosophy and science, the arts, and theology. 3. To make this heritage of great minds part of one’s own thinking. 4. To develop competence in reading philosophy, to lay a foundation for understanding contemporary thought, and to prepare for more critical and constructive work. Procedure 1. The primary sources are of major importance, and you will learn to read and understand them for yourself. Outline them as you read: they provide depth of insight and involve you in dialogue with the philosophers themselves. Ask first, What does he say? The, how does this relate to What else he says, and to what his predecessors said? Then, appraise his assumptions and arguments. -

The Theory of Descriptions 1. Bertrand Russell (1872-1970): Mathematician, Logician, and Philosopher

Louis deRosset { Spring 2019 Russell: The Theory of Descriptions 1. Bertrand Russell (1872-1970): mathematician, logician, and philosopher. He's one of the founders of analytic philosophy. \On Denoting" is a founding document of analytic philosophy. It is a paradigm of philosophical analysis. An analysis of a concept/phenomenon c: a recipe for eliminating c-vocabulary from our theories which still captures all of the facts the c-vocabulary targets. FOR EXAMPLE: \The Name View Analysis of Identity." 2. Russell's target: Denoting Phrases By a \denoting phrase" I mean a phrase such as any one of the following: a man, some man, any man, every man, all men, the present King of England, the present King of France, the centre of mass of the Solar System at the first instant of the twentieth century, the revolution of the earth round the sun, the revolution of the sun round the earth. (479) Includes: • universals: \all F 's" (\each"/\every") • existentials: \some F " (\at least one") • indefinite descriptions: \an F " • definite descriptions: \the F " Later additions: • negative existentials: \no F 's" (480) • Genitives: \my F " (\your"/\their"/\Joe's"/etc.) (484) • Empty Proper Names: \Apollo", \Hamlet", etc. (491) Russell proposes to analyze denoting phrases. 3. Why Analyze Denoting Phrases? Russell's Project: The distinction between acquaintance and knowledge about is the distinction between the things we have presentation of, and the things we only reach by means of denoting phrases. [. ] In perception we have acquaintance with the objects of perception, and in thought we have acquaintance with objects of a more abstract logical character; but we do not necessarily have acquaintance with the objects denoted by phrases composed of words with whose meanings we are ac- quainted. -

Malebranche's Augustinianism and the Mind's Perfection

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations Spring 2010 Malebranche's Augustinianism and the Mind's Perfection Jason Skirry University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Skirry, Jason, "Malebranche's Augustinianism and the Mind's Perfection" (2010). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 179. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/179 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/179 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Malebranche's Augustinianism and the Mind's Perfection Abstract This dissertation presents a unified interpretation of Malebranche’s philosophical system that is based on his Augustinian theory of the mind’s perfection, which consists in maximizing the mind’s ability to successfully access, comprehend, and follow God’s Order through practices that purify and cognitively enhance the mind’s attention. I argue that the mind’s perfection figures centrally in Malebranche’s philosophy and is the main hub that connects and reconciles the three fundamental principles of his system, namely, his occasionalism, divine illumination, and freedom. To demonstrate this, I first present, in chapter one, Malebranche’s philosophy within the historical and intellectual context of his membership in the French Oratory, arguing that the Oratory’s particular brand of Augustinianism, initiated by Cardinal Bérulle and propagated by Oratorians such as Andre Martin, is at the core of his philosophy and informs his theory of perfection. Next, in chapter two, I explicate Augustine’s own theory of perfection in order to provide an outline, and a basis of comparison, for Malebranche’s own theory of perfection. -

Chapter One Transcendentalism and the Aesthetic Critique Of

Chapter One Transcendentalism and the Aesthetic Critique of Modernity Thinking of the aesthetic as both potentially ideological and potentially utopian allows us to understand the social implications of modern aes- thetics. The aesthetic experience can serve to evade questions of justice and equality as much as it offers the opportunity for a vision of freedom. If the Transcendentalists stand at the end of a Romantic tradition which has always been aware of the utopian dimension of the aesthetic, why should they have cherished the consolation the aesthetic experience of- fers while at the same time forfeiting its critical implications, which have been so important for the British and the early German Romantics? Is the American variety of Romanticism really much more submissive than European Romanticism with all its revolutionary fervor? Is it really true that “the writing of the Transcendentalists, and all those we may wish to consider as Romantics, did not have this revolutionary social dimension,” as Tony Tanner has suggested (1987, 38)? The Transcendentalists were critical of established religious dogma and received social conventions – so why should their aesthetics be apolitical or even adapt to dominant ideologies? In fact, the Transcendentalists were well aware of the philo- sophical and social radicalism of the aesthetic – which, however, is not to say that all of them wholeheartedly embraced it. While the Transcendentalists’ American background (New England’s Puritan legacy and the Unitarian church from which they emerged) is crucial for an understanding of their social, religious, and philosophical thought, it is worth casting an eye across the ocean to understand their concept of beauty since the Transcendentalists were also heir to a long- standing tradition of transatlantic Romanticism which addressed the re- lationship between aesthetic experience, utopia, and social criticism. -

Skill in Epistemology I: Skill and Knowledge

Skill in Epistemology I: Skill and Knowledge Carlotta Pavese Abstract Knowledge and skill are intimately connected. In this essay, I discuss the question of their relationship and of which (if any) is prior to which in the order of explanation. I review some of the answers that have been given thus far in the literature, with a particular focus on the many foundational issues in epistemology that intersect with the philosophy of skill. 1 Introduction Knowledge and skill are intimately connected. Scientists cannot get new knowledge without developing their skills for devising experiments. And skilled artists, scientists, and mathematicians must know a lot about their area of expertise in order to perform skillfully and routinely manifest that knowledge through their skillful performances. Despite this obvious interrelationship, knowledge and skill have received different treatment in analytic epistemology. While philosophers in this tradition have long been in the business of understanding and defining knowledge, the topic of skill has been marginalized. It is only quite recently that skills have made a powerful entrance in two epistemological debates: the debate on virtue epistemology and the debate on the nature of know how. In this essay, I discuss the question of the relationship between skill and knowledge (Section §2) and of which (if any) is prior to which in the order of explanation (Section §3), with an eye to highlighting the many foundational issues in epistemology that intersect with the philosophy of skill. In section §3, I will start discussing the relationship between skill and know how, which will be the main topic of the sequel to this essay. -

Epistemology and Philosophy of Science

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Wed Apr 06 2016, NEWGEN Chapter 11 Epistemology and Philosophy of Science Otávio Bueno 1 Introduction It is a sad fact of contemporary epistemology and philosophy of science that there is very little substantial interaction between the two fields. Most epistemological theo- ries are developed largely independently of any significant reflection about science, and several philosophical interpretations of science are articulated largely independently of work done in epistemology. There are occasional exceptions, of course. But the general point stands. This is a missed opportunity. Closer interactions between the two fields would be ben- eficial to both. Epistemology would gain from a closer contact with the variety of mech- anisms of knowledge generation that are produced in scientific research, with attention to sources of bias, the challenges associated with securing truly representative samples, and elaborate collective mechanisms to secure the objectivity of scientific knowledge. It would also benefit from close consideration of the variety of methods, procedures, and devices of knowledge acquisition that shape scientific research. Epistemological theories are less idealized and more sensitive to the pluralism and complexities involved in securing knowledge of various features of the world. Thus, philosophy of science would benefit, in turn, from a closer interaction with epistemology, given sophisticated conceptual frameworks elaborated to refine and characterize our understanding of knowledge, -

Schelling, Hunter and British Idealism Tilottama Rajan1

47 The Official Journal of the North American Schelling Society Volume 1 (2018) The Asystasy of the Life Sciences: Schelling, Hunter and British Idealism Tilottama Rajan1 In 1799 the British Crown purchased 13,000 fossils and specimens from the estate of John Hunter (1728-93). This “vast Golgotha”2 then became the object of attempts to classify and institutionalize the work of one of the most singular and polymathic figures in the British life sciences whose work encompassed medicine and surgery, physiology, comparative anatomy and geology. The result was the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons, separate Lecture Series on comparative anatomy and surgery from 1810, and “Orations” on Hunter’s birthday from 1814. Almost symbolically, these efforts were disrupted by the burning of twenty folio volumes of Hunter’s notes on the specimens in 1823 by his brother-in-law and executor Sir Everard Home. Home may have wanted to emerge from Hunter’s shadow or disguise his borrowings but saw nothing wrong in his actions and divulged them to Hunter’s amanuensis William Clift (by then Chief Conservator of the Museum). Having based over ninety articles on Hunter’s work, Home claimed he had published and acknowledged everything of value, and that Hunter wanted him to burn the papers, though interestingly he waited thirty years to do so. He also claimed he had wanted to present Hunter’s work in more complete form, and spare him from charges of irreligion. And indeed it had been recently that the debate between John Abernethy and William Lawrence had broken out, over whether Hunter and science should be aligned with religion or materialism: a debate 1 The author acknowledges the support of the Canada Research Chairs Program in the preparation of this article. -

A Constructive Theology of Truth As a Divine Name with Reference to the Bible and Augustine

A Constructive Theology of Truth as a Divine Name with reference to the Bible and Augustine by Emily Sumner Kempson Murray Edwards College September 2019 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Copyright © 2020 Emily Sumner Kempson 2 Preface This thesis is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. 3 4 A Constructive Theology of Truth as a Divine Name with Reference to the Bible and Augustine (Summary) Emily Sumner Kempson This study is a work of constructive theology that retrieves the ancient Christian understanding of God as truth for contemporary theological discourse and points to its relevance to biblical studies and philosophy of religion. The contribution is threefold: first, the thesis introduces a novel method for constructive theology, consisting of developing conceptual parameters from source material which are then combined into a theological proposal. -

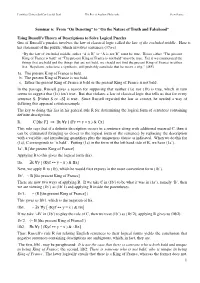

Using Russell's Theory of Descriptions to S

Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú The Rise of Analytic Philosophy Scott Soames Seminar 6: From “On Denoting” to “On the Nature of Truth and Falsehood” Using Russell’s Theory of Descriptions to Solve Logical Puzzles One of Russell’s puzzles involves the law of classical logic called the law of the excluded middle. Here is his statement of the puzzle, which involves sentences (37a-c). “By the law of excluded middle, either “A is B” or “A is not B” must be true. Hence either “The present King of France is bald” or “The present King of France is not bald” must be true. Yet if we enumerated the things that are bald and the things that are not bald, we should not find the present King of France in either list. Hegelians, who love a synthesis, will probably conclude that he wears a wig.” (485) 1a. The present King of France is bald. b. The present King of France is not bald. c. Either the present King of France is bald or the present King of France is not bald. In the passage, Russell gives a reason for supposing that neither (1a) nor (1b) is true, which in turn seems to suggest that (1c) isn’t true. But that violates a law of classical logic that tells us that for every sentence S, ⎡Either S or ~S⎤ is true. Since Russell regarded the law as correct, he needed a way of defusing this apparent counterexample. The key to doing this lies in his general rule R for determining the logical form of sentences containing definite descriptions.