Alpata: a Journal of History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calculated for the Use of the State Of

3i'R 317.3M31 H41 A Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from University of IVIassachusetts, Boston http://www.archive.org/details/pocketalmanackfo1839amer MASSACHUSETTS REGISTER, AND mmwo states ©alrntiar, 1839. ALSO CITY OFFICERS IN BOSTON, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. BOSTON: PUBLISHED BY JAMES LORING, 13 2 Washington Street. ECLIPSES IN 1839. 1. The first will be a great and total eclipse, on Friday March 15th, at 9h. 28m. morning, but by reason of the moon's south latitude, her shadow will not touch any part of North America. The course of the general eclipse will be from southwest to north- east, from the Pacific Ocean a little west of Chili to the Arabian Gulf and southeastern part of the Mediterranean Sea. The termination of this grand and sublime phenomenon will probably be witnessed from the summit of some of those stupendous monuments of ancient industry and folly, the vast and lofty pyramids on the banks of the Nile in lower Egypt. The principal cities and places that will be to- tally shadowed in this eclipse, are Valparaiso, Mendoza, Cordova, Assumption, St. Salvador and Pernambuco, in South America, and Sierra Leone, Teemboo, Tombucto and Fezzan, in Africa. At each of these places the duration of total darkness will be from one to six minutes, and several of the planets and fixed stars will probably be visible. 2. The other will also be a grand and beautiful eclipse, on Satur- day, September 7th, at 5h. 35m. evening, but on account of the Mnon's low latitude, and happening so late in the afternoon, no part of it will be visible in North America. -

The School Board of Escambia County, Florida

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF ESCAMBIA COUNTY, FLORIDA MINUTES, MAY 18, 2021 The School Board of Escambia County, Florida, convened in Regular Meeting at 5:30 p.m., in Room 160, at the J.E. Hall Educational Services Center, 30 East Texar Drive, Pensacola, Florida, with the following present: Chair: Mr. William E. Slayton (District V) Vice Chair: Mr. Kevin L. Adams (District I) Board Members: Mr. Paul Fetsko (District II) Dr. Laura Dortch Edler (District III) Mrs. Patricia Hightower (District IV) School Board General Counsel: Mrs. Ellen Odom Superintendent of Schools: Dr. Timothy A. Smith Advertised in the Pensacola News Journal on April 30, 2021 – Legal No. 4693648 I. CALL TO ORDER Chair Slayton called the Regular Meeting to order at 5:30 p.m. a. Invocation and Pledge of Allegiance (NOTE: It is the tradition of the Escambia County School Board to begin their business meeting with an invocation or motivational moment followed by the Pledge of Allegiance.) Dr. Edler introduced Reverend Lawrence Powell, minister at Good Hope A.M.E. Church of Warrington in Pensacola, Florida. Reverend Powell delivered the invocation and Dr. Edler led the Pledge of Allegiance to the United States of America. b. Adoption of Agenda Superintendent Smith listed changes made to the agenda since initial publication and prior to this session. Chair Slayton advised that Florida Statutes and School Board Rule require that changes made to an agenda after publication be based on a finding of good cause, as determined by the person designated to preside over the meeting, and stated in the record. -

Performance, Aesthetics, and the Unfinished Haitian Revolution Jeremy Matthew Glick

The Black Radical Tragic America and the Long 19th Century General Editors David Kazanjian, Elizabeth McHenry, and Priscilla Wald Black Frankenstein: The Making of an American Metaphor Elizabeth Young Neither Fugitive nor Free: Atlantic Slavery, Freedom Suits, and the Legal Culture of Travel Edlie L. Wong Shadowing the White Man’s Burden: U.S. Imperialism and the Problem of the Color Line Gretchen Murphy Bodies of Reform: The Rhetoric of Character in Gilded- Age America James B. Salazar Empire’s Proxy: American Literature and U.S. Imperialism in the Philippines Meg Wesling Sites Unseen: Architecture, Race, and American Literature William A. Gleason Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights Robin Bernstein American Arabesque: Arabs and Islam in the Nineteenth Century Imaginary Jacob Rama Berman Racial Indigestion: Eating Bodies in the Nineteenth Century Kyla Wazana Tompkins Idle Threats: Men and the Limits of Productivity in Nineteenth- Century America Andrew Lyndon Knighton The Traumatic Colonel: The Founding Fathers, Slavery, and the Phantasmatic Aaron Burr Michael J. Drexler and Ed White Unsettled States: Nineteenth- Century American Literary Studies Edited by Dana Luciano and Ivy G. Wilson Sitting in Darkness: Mark Twain, Asia, and Comparative Racialization Hsuan L. Hsu Picture Freedom: Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century Jasmine Nichole Cobb Stella Émeric Bergeaud Translated by Lesley Curtis and Christen Mucher Racial Reconstruction: Black Inclusion, Chinese Exclusion, and the -

Black Citizenship, Black Sovereignty: the Haitian Emigration Movement and Black American Politics, 1804-1865

Black Citizenship, Black Sovereignty: The Haitian Emigration Movement and Black American Politics, 1804-1865 Alexander Campbell History Honors Thesis April 19, 2010 Advisor: Françoise Hamlin 2 Table of Contents Timeline 5 Introduction 7 Chapter I: Race, Nation, and Emigration in the Atlantic World 17 Chapter II: The Beginnings of Black Emigration to Haiti 35 Chapter III: Black Nationalism and Black Abolitionism in Antebellum America 55 Chapter IV: The Return to Emigration and the Prospect of Citizenship 75 Epilogue 97 Bibliography 103 3 4 Timeline 1791 Slave rebellion begins Haitian Revolution 1831 Nat Turner rebellion, Virginia 1804 Independent Republic of Haiti declared, Radical abolitionist paper The Liberator with Jean-Jacques Dessalines as President begins publication 1805 First Constitution of Haiti Written 1836 U.S. Congress passes “gag rule,” blocking petitions against slavery 1806 Dessalines Assassinated; Haiti divided into Kingdom of Haiti in the North, Republic of 1838 Haitian recognition brought to U.S. House Haiti in the South. of Representatives, fails 1808 United States Congress abolishes U.S. 1843 Jean-Pierre Boyer deposed in coup, political Atlantic slave trade chaos follows in Haiti 1811 Paul Cuffe makes first voyage to Africa 1846 Liberia, colony of American Colonization Society, granted independence 1816 American Colonization Society founded 1847 General Faustin Soulouque gains power in 1817 Paul Cuffe dies Haiti, provides stability 1818 Prince Saunders tours U.S. with his 1850 Fugitive Slave Act passes U.S. Congress published book about Haiti Jean-Pierre Boyer becomes President of 1854 Martin Delany holds National Emigration Republic of Haiti Convention Mutiny of the Holkar 1855 James T. -

The Autobiography of Increase Mather

The Autobiography of Increase Mather I-DÎTED BY M. G. HALL j^ STRETCH a point to call this maTiuscript an W autobiography. Actually it i.s a combinatioa of aiito- biograpliy and political tract and journal, in which the most formal part comes first and the rest was added on lo it as occasion offered. But, the whole is certainly auto- biographical and covers Increase Mather's life faithfull}'. It was tlie mainstay of Cotton Mather's famous biograpliy Pareniator, which appeared in 1724, and of Kenneth Mur- dock's Increase Miiîher, whicli was published two liundred and one years later.^ Printing the autobiography Jiere is in no way designed to improve or correct Mather's biog- raphers. They have done well by him. But their premises and purposes were inevitabiy different from liis. I'he present undertaking is to let Increase Matlier also be lieard on tlie subject of himself. Readers who wish to do so are invited to turn witliout more ado to page 277, where tliey may read the rjriginal without interruption. For tjiose who want to look before they leap, let me remind tliem of tlie place Increase Mather occu[!Íes in tlie chronology of his family. Three generations made a dy- nasty extraordhiary in any country; colossal in the frame of ' Cotton Msther, Pami'.at'^r. Mnnoirs if Remarkables in the Life and Death o/ the F.vtr- MemorahU Dr. Increase Múíker (Boston, 1724). Kenneth B. Murdock, Incrfasr Mathfr, the Foremost .Imerican Puritan (Cambridge, 1925)- Since 1925 three books bearing importantly on hicrcase Mather have been published: Thomas J. -

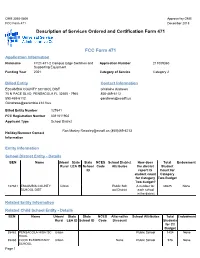

Description of Services Ordered and Certification Form 471 FCC Form

OMB 3060-0806 Approval by OMB FCC Form 471 December 2018 Description of Services Ordered and Certification Form 471 FCC Form 471 Application Information Nickname FY21-471-2 Campus Edge Switches and Application Number 211009360 Supporting Equipment Funding Year 2021 Category of Service Category 2 Billed Entity Contact Information ESCAMBIA COUNTY SCHOOL DIST Ghislaine Andrews 75 N PACE BLVD PENSACOLA FL 32505 - 7965 850-469-6112 850-469-6112 [email protected] [email protected] Billed Entity Number 127641 FCC Registration Number 0011611902 Applicant Type School District Ron Mosley [email protected] (850)469-6213 Holiday/Summer Contact Information Entity Information School District Entity - Details BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES School District How does Total Endowment Rural LEA ID School Code Attributes the district Student ID report its Count for student count Category for Category Two Budget Two budget? 127641 ESCAMBIA COUNTY Urban Public Sch A number for 38625 None SCHOOL DIST ool District each school in the district Related Entity Information Related Child School Entity - Details BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES Alternative School Attributes Total Endowment Rural LEA ID School ID Code Discount Students for C2 Budget 35482 PENSACOLA HIGH SC Urban Public School 1424 None HOOL 35486 COOK ELEMENTARY Urban None Public School 578 None SCHOOL Page 1 BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES Alternative School Attributes Total Endowment Rural LEA ID School ID Code Discount Students for C2 Budget 35493 BROWN BARGE MIDD Urban None Public School 563 None LE SCHOOL 35494 CORDOVA PARK ELE Urban None Public School 628 None MENTARY SCHOOL 35496 O. -

Spectral Evidence’ in Longfellow, Miller and Trump

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses May 2021 Weaponizing Faith: ‘Spectral Evidence’ in Longfellow, Miller and Trump Paul Hyde Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Hyde, Paul, "Weaponizing Faith: ‘Spectral Evidence’ in Longfellow, Miller and Trump" (2021). All Theses. 3560. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/3560 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WEAPONIZING FAITH: “SPECTRAL EVIDENCE” IN LONGFELLOW, MILLER AND TRUMP A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts English by Paul Hyde May 2021 Accepted by: Dr. Michael LeMahieu, Committee Chair Dr. Cameron Bushnell Dr. Jonathan Beecher Field ABSTRACT This thesis explores a particular type of irrational pattern-seeking — specifically, “spectral evidence” — in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Giles Corey of the Salem Farms (1872) and Arthur Miller’s The Crucible (1953). It concludes with observations of this concept’s continued and concerning presence by other names in Trump-era politics. The two works by Longfellow and Miller make a natural pairing because both are plays inspired by the Salem witchcraft trials (1692-93), a notorious historical miscarriage of justice. Robert Warshow calls the Salem witchcraft trials, aside from slavery, “the most disconcerting single episode in our history: the occurrence of the unthinkable on American soil, and in what our schools have rather successfully taught us to think of as the very ‘cradle of Americanism” (211). -

Empowering Popularity: the Fuel Behind a Witch-Hunt

EMPOWERING POPULARITY: THE FUEL BEHIND A WITCH-HUNT ________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University ________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Graduation From the Honors Tutorial College With the degree of Bachelor of Arts in History ________________________________ Written by Grace Konyar April 2017 Table of Contents List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………….2 Introduction………………………………………………………………………….3 Chapter One………………………………………………………………………..10 Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story: The Development of Witchcraft as a Gendered Crime Chapter Two………………………………………………………………………………...31 The World Turned Upside Down: The Fragility of the Suffolk and Essex Witch-Hunts Chapter Three ……………………………………………………………………………...52 That Would Be Enough: The Tipping Point of Spectral Evidence Chapter Four………………………………………………………………………74 Satisfied: The Balance of Ethics and Fame Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………….93 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………..97 1 List of Figures Image 1: Frontispiece, Matthew Hopkins, The Discovery of Witches, London, 1647…...........................................................................................................................40 Image 2: Indictment document 614 of the Essex Summer Sessions for Maria Sterling. Courtesy of The National Archives- Kew, ASSI 35/86/1/72. Photograph by the author………………………………………………………………………………....41 Image 3: Frontispiece, A True Relation of the Araignment of eighteen Witches, London, 1945……………………………………...……….…………………………48 -

ECPSF Announces 2021 Mira Award Recipients

Kim Stefansson Escambia County School District Public Relations Coordinator [email protected] 850-393-0539 (Cell) NEWS RELEASE May 18, 2021 ECPSF Announces 2021 Mira Award Recipients Each year the Escambia County Public Schools Foundation has celebrated the unique gifts and creative talents of many amazing high school students from the Escambia County (Fla) School District’s seven high schools with the presentation of the Mira Creative Arts Awards. Mira is a shortened Latin term meaning, “brightest star,” and the awards were established by teachers to recognize students who demonstrate talents in the creative arts. Students are nominated by their instructors for this honor. The Foundation is thrilled to celebrate these artistic talents and gifts by honoring amazing high school seniors every year. This celebration was helped this year by the generosity of their event sponsor, Blues Angel Music. This year the Mira awards ceremony was held online. Please click here to view and download the presentation. Students are encouraged to share the link with their family members and friends so they can share in their celebration. Link: https://drive.google.com/file/d/10ERRfzPud1npcygZSYBuD7BF0- TBMWGK/view Students will receive a custom-made medallion during their school's senior awards ceremony so they may wear it during their graduation ceremony with their cap and gown. Congratulations go to all of the Mira awardees on behalf of the Escambia County Public Schools Foundation Board of Directors. The Class of 2021 Escambia County Public Schools -

WILLARD, Samuel, Vice President of Harvard College, Born at Concord, Massachusetts, January 31, 1640, Was a Son of Simon Willard, a Man of Considerable Distinction

PEOPLE MENTIONED IN CAPE COD 1 CONCORD’S “NATIVE” COLLEGE GRADS: REVEREND SAMUEL SYMON WILLARD “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY 1. Only those native to (which is to say, born in) Concord, Massachusetts — and among those accomplished natives, only those whose initials are not HDT. HDT WHAT? INDEX THE PEOPLE OF CAPE COD:REVEREND SAMUEL SYMON WILLARD PEOPLE MENTIONED IN CAPE COD CAPE COD: After his marriage with the daughter of Mr. Willard PEOPLE OF (pastor of the South Church in Boston), he was sometimes invited CAPE COD by that gentleman to preach in his pulpit. Mr. Willard possessed a graceful delivery, a masculine and harmonious voice; and, though he did not gain much reputation by his ‘Body of Divinity,’ which is frequently sneered at, particularly by those who have not read it, yet in his sermons are strength of thought, and energy of language. The natural consequence was that he was generally admired. Mr. Treat having preached one of his best discourses to the congregation of his father-in-law, in his usual unhappy manner, excited universal disgust; and several nice judges waited on Mr. Willard, and begged that Mr. Treat, who was a worthy, pious man, it was true, but a wretched preacher, might never be invited into his pulpit again. To this request Mr. Willard made no reply; but he desired his son-in-law to lend him the discourse; which, being left with him, he delivered it without alteration, to his people, a few weeks after. They ran to Mr. -

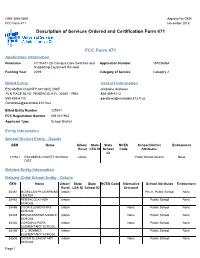

Description of Services Ordered and Certification Form 471 FCC

OMB 3060-0806 Approval by OMB FCC Form 471 November 2015 Description of Services Ordered and Certification Form 471 FCC Form 471 Application Information Nickname FY19-471-2A Campus Core Switches and Application Number 191036964 Supporting Equipment Revised Funding Year 2019 Category of Service Category 2 Billed Entity Contact Information ESCAMBIA COUNTY SCHOOL DIST Ghislaine Andrews 75 N PACE BLVD PENSACOLA FL 32505 - 7965 850-469-6112 850-469-6112 [email protected] [email protected] Billed Entity Number 127641 FCC Registration Number 0011611902 Applicant Type School District Entity Information School District Entity - Details BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES School District Endowment Rural LEA ID School Code Attributes ID 127641 ESCAMBIA COUNTY SCHOOL Urban Public School District None DIST Related Entity Information Related Child School Entity - Details BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES Code Alternative School Attributes Endowment Rural LEA ID School ID Discount 35481 MCMILLAN PK LEARNING Urban Pre-K; Public School None CENTER 35482 PENSACOLA HIGH Urban Public School None SCHOOL 35486 COOK ELEMENTARY Urban None Public School None SCHOOL 35493 BROWN BARGE MIDDLE Urban None Public School None SCHOOL 35494 CORDOVA PARK Urban None Public School None ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 35496 O. J. SEMMES Urban Public School None ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 35503 SUTER ELEMENTARY Urban None Public School None SCHOOL Page 1 BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES Code Alternative School Attributes Endowment Rural LEA ID School ID Discount 35504 WOODHAM MIDDLE -

Cotton Mathers's Wonders of the Invisible World: an Authoritative Edition

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English 1-12-2005 Cotton Mathers's Wonders of the Invisible World: An Authoritative Edition Paul Melvin Wise Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Wise, Paul Melvin, "Cotton Mathers's Wonders of the Invisible World: An Authoritative Edition." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2005. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/5 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COTTON MATHER’S WONDERS OF THE INVISIBLE WORLD: AN AUTHORITATIVE EDITION by PAUL M. WISE Under the direction of Reiner Smolinski ABSTRACT In Wonders of the Invisible World, Cotton Mather applies both his views on witchcraft and his millennial calculations to events at Salem in 1692. Although this infamous treatise served as the official chronicle and apologia of the 1692 witch trials, and excerpts from Wonders of the Invisible World are widely anthologized, no annotated critical edition of the entire work has appeared since the nineteenth century. This present edition seeks to remedy this lacuna in modern scholarship, presenting Mather’s seventeenth-century text next to an integrated theory of the natural causes of the Salem witch panic. The likely causes of Salem’s bewitchment, viewed alongside Mather’s implausible explanations, expose his disingenuousness in writing about Salem. Chapter one of my introduction posits the probability that a group of conspirators, led by the Rev.