Weather Patterns and Weather Types

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 9 : Air Mass Air Masses Source Regions

4/29/2011 Chapter 9 : Air Mass • Air masses Contain uniform temperature and humidity characteristics. • Fronts Boundaries between unlike air • Air Masses masses. • Fronts • Fronts on Weather Maps ESS124 ESS124 Prof. Jin-Jin-YiYi Yu Prof. Jin-Jin-YiYi Yu Air Masses • Air masses have fairly uniform temperature and moisture Source Regions content in horizontal direction (but not uniform in vertical). • Air masses are characterized by their temperature and humidity • The areas of the globe where air masses from are properties. called source regions. • The properties of air masses are determined by the underlying • A source region must have certain temperature surface properties where they originate. and humidity properties that can remain fixed for a • Once formed, air masses migrate within the general circulation. substantial length of time to affect air masses • UidilidliliUpon movement, air masses displace residual air over locations above it. thus changing temperature and humidity characteristics. • Air mass source regions occur only in the high or • Further, the air masses themselves moderate from surface low latitudes; middle latitudes are too variable. influences. ESS124 ESS124 Prof. Jin-Jin-YiYi Yu Prof. Jin-Jin-YiYi Yu 1 4/29/2011 Cold Air Masses Warm Air Masses January July January July • The cent ers of cold ai r masses are associ at ed with hi gh pressure on surf ace weath er • The cen ters o f very warm a ir masses appear as sem i-permanentit regions o flf low maps. pressure on surface weather maps. • In summer, when the oceans are cooler than the landmasses, large high-pressure • In summer, low-pressure areas appear over desert areas such as American centers appear over North Atlantic (Bermuda high) and Pacific (Pacific high). -

Weather Numbers Multiple Choices I

Weather Numbers Answer Bank A. 1 B. 2 C. 3 D. 4 E. 5 F. 25 G. 35 H. 36 I. 40 J. 46 K. 54 L. 58 M. 72 N. 74 O. 75 P. 80 Q. 100 R. 910 S. 1000 T. 1010 U. 1013 V. ½ W. ¾ 1. Minimum wind speed for a hurricane in mph N 74 mph 2. Flash-to-bang ratio. For every 10 second between lightning flash and thunder, the storm is this many miles away B 2 miles as flash to bang ratio is 5 seconds per mile 3. Minimum diameter of a hailstone in a severe storm (in inches) A 1 inch (formerly ¾ inches) 4. Standard sea level pressure in millibars U 1013.25 millibars 5. Minimum wind speed for a severe storm in mph L 58 mph 6. Minimum wind speed for a blizzard in mph G 35 mph 7. 22 degrees Celsius converted to Fahrenheit M 72 22 x 9/5 + 32 8. Increments between isobars in millibars D 4mb 9. Minimum water temperature in Fahrenheit for hurricane development P 80 F 10. Station model reports pressure as 100, what is the actual pressure in millibars T 1010 (remember to move decimal to left and then add either 10 or 9 100 become 10.0 910.0mb would be extreme low so logic would tell you it would be 1010.0mb) Multiple Choices I 1. A dry line front is also known as a: a. dew point front b. squall line front c. trough front d. Lemon front e. Kelvin front 2. -

Catastrophic Weather Perils in the United States Climate Drivers Catastrophic Weather Perils in the United States Climate Drivers

Catastrophic Weather Perils in the United States Climate Drivers Catastrophic Weather Perils in the United States Climate Drivers Table of Contents 2 Introduction 2 Atlantic Hurricanes –2 Formation –3 Climate Impacts •3 Atlantic Sea Surface Temperatures •4 El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) •6 North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) •7 Quasi-Biennial Oscillation (QBO) –Summary8 8 Severe Thunderstorms –8 Formation –9 Climate Impacts •9 El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) 10• Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) 10– Other Climate Impacts 10–Summary 11 Wild Fire 11– Formation 11– Climate Impacts 11• El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) & Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) 12– Other Climate / Weather Variables 12–Summary May 2012 The information contained in this document is strictly proprietary and confidential. 1 Catastrophic Weather Perils in the United States Climate Drivers INTRODUCTION The last 10 years have seen a variety of weather perils cause significant insured losses in the United States. From the wild fires of 2003, hurricanes of 2004 and 2005, to the severe thunderstorm events in 2011, extreme weather has the appearance of being the norm. The industry has experienced over $200B in combined losses from catastrophic weather events in the US since 2002. While the weather is often seen as a random, chaotic thing, there are relatively predictable patterns (so called “climate states”) in the weather which can be used to inform our expectations of extreme weather events. An oft quoted adage is that “climate is what you expect; weather is what you actually observe.” A more useful way to think about the relationship between weather and climate is that the climate is the mean state of the atmosphere (either locally or globally) which changes over time, and weather is the variation around that mean. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

The Effects of Diabatic Heating on Upper

THE EFFECTS OF DIABATIC HEATING ON UPPER- TROPOSPHERIC ANTICYCLOGENESIS by Ross A. Lazear A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN - MADISON 2007 i Abstract The role of diabatic heating in the development and maintenance of persistent, upper- tropospheric, large-scale anticyclonic anomalies in the subtropics (subtropical gyres) and middle latitudes (blocking highs) is investigated from the perspective of potential vorticity (PV) non-conservation. The low PV within blocking anticyclones is related to condensational heating within strengthening upstream synoptic-scale systems. Additionally, the associated convective outflow from tropical cyclones (TCs) is shown to build upper- tropospheric, subtropical anticyclones. Not only do both of these large-scale flow phenomena have an impact on the structure and dynamics of neighboring weather systems, and consequently the day-to-day weather, the very persistence of these anticyclones means that they have a profound influence on the seasonal climate of the regions in which they exist. A blocking index based on the meridional reversal of potential temperature on the dynamic tropopause is used to identify cases of wintertime blocking in the North Atlantic from 2000-2007. Two specific cases of blocking are analyzed, one event from February 1983, and another identified using the index, from January 2007. Parallel numerical simulations of these blocking events, differing only in one simulation’s neglect of the effects of latent heating of condensation (a “fake dry” run), illustrate the importance of latent heating in the amplification and wave-breaking of both blocking events. -

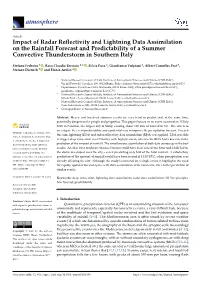

Impact of Radar Reflectivity and Lightning Data Assimilation

atmosphere Article Impact of Radar Reflectivity and Lightning Data Assimilation on the Rainfall Forecast and Predictability of a Summer Convective Thunderstorm in Southern Italy Stefano Federico 1 , Rosa Claudia Torcasio 1,* , Silvia Puca 2, Gianfranco Vulpiani 2, Albert Comellas Prat 3, Stefano Dietrich 1 and Elenio Avolio 4 1 National Research Council of Italy, Institute of Atmospheric Sciences and Climate (CNR-ISAC), Via del Fosso del Cavaliere 100, 00133 Rome, Italy; [email protected] (S.F.); [email protected] (S.D.) 2 Dipartimento Protezione Civile Nazionale, 00189 Rome, Italy; [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (G.V.) 3 National Research Council of Italy, Institute of Atmospheric Sciences and Climate (CNR-ISAC), Strada Pro.Le Lecce-Monteroni, 73100 Lecce, Italy; [email protected] 4 National Research Council of Italy, Institute of Atmospheric Sciences and Climate (CNR-ISAC), Zona Industriale ex SIR, 88046 Lamezia Terme, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Heavy and localized summer events are very hard to predict and, at the same time, potentially dangerous for people and properties. This paper focuses on an event occurred on 15 July 2020 in Palermo, the largest city of Sicily, causing about 120 mm of rainfall in 3 h. The aim is to investigate the event predictability and a potential way to improve the precipitation forecast. To reach Citation: Federico, S.; Torcasio, R.C.; this aim, lightning (LDA) and radar reflectivity data assimilation (RDA) was applied. LDA was able Puca, S.; Vulpiani, G.; Comellas Prat, to trigger deep convection over Palermo, with high precision, whereas the RDA had a key role in the A.; Dietrich, S.; Avolio, E. -

Chapter 7 – Atmospheric Circulations (Pp

Chapter 7 - Title Chapter 7 – Atmospheric Circulations (pp. 165-195) Contents • scales of motion and turbulence • local winds • the General Circulation of the atmosphere • ocean currents Wind Examples Fig. 7.1: Scales of atmospheric motion. Microscale → mesoscale → synoptic scale. Scales of Motion • Microscale – e.g. chimney – Short lived ‘eddies’, chaotic motion – Timescale: minutes • Mesoscale – e.g. local winds, thunderstorms – Timescale mins/hr/days • Synoptic scale – e.g. weather maps – Timescale: days to weeks • Planetary scale – Entire earth Scales of Motion Table 7.1: Scales of atmospheric motion Turbulence • Eddies : internal friction generated as laminar (smooth, steady) flow becomes irregular and turbulent • Most weather disturbances involve turbulence • 3 kinds: – Mechanical turbulence – you, buildings, etc. – Thermal turbulence – due to warm air rising and cold air sinking caused by surface heating – Clear Air Turbulence (CAT) - due to wind shear, i.e. change in wind speed and/or direction Mechanical Turbulence • Mechanical turbulence – due to flow over or around objects (mountains, buildings, etc.) Mechanical Turbulence: Wave Clouds • Flow over a mountain, generating: – Wave clouds – Rotors, bad for planes and gliders! Fig. 7.2: Mechanical turbulence - Air flowing past a mountain range creates eddies hazardous to flying. Thermal Turbulence • Thermal turbulence - essentially rising thermals of air generated by surface heating • Thermal turbulence is maximum during max surface heating - mid afternoon Questions 1. A pilot enters the weather service office and wants to know what time of the day she can expect to encounter the least turbulent winds at 760 m above central Kansas. If you were the weather forecaster, what would you tell her? 2. -

Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies the University of Oklahoma

COOPERATIVE INSTITUTE FOR MESOSCALE METEOROLOGICAL STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA Final Report for Cooperative Agreement NA67RJ0150 July 1, 1996-June 30, 2001 Peter J. Lamb, Director Randy A. Peppler, Associate Director John V. Cortinas, Jr., Assistant Director I. Introduction The University of Oklahoma (OU) and NOAA established the Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies (CIMMS) in 1978. Through 1995, CIMMS promoted cooperation and collaboration on problems of mutual interest among research scientists in the NOAA Environmental Research Laboratories (ERL) National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL), and faculty, postdoctoral scientists, and students in the School of Meteorology and other academic departments at OU. The Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) between OU and NOAA that established CIMMS was updated in 1995 to include the National Weather Service (NWS). This expanded the formal OU/NOAA collaboration to the Radar Operations Center (ROC) for the WSR-88D (NEXRAD) Program, the NCEP (National Centers for Environmental Prediction) Storm Prediction Center (SPC), and our local NWS Forecast Office, all located in Norman, Oklahoma. Management of the NSSL came under the auspices of the NOAA Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR) in 1999. The Norman NOAA groups at that time became known as the NOAA Weather Partners. Through CIMMS, university scientists collaborate with NOAA scientists on research supported by NOAA programs and laboratories as well as by other agencies such as the National Science Foundation (NSF), the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). This document describes the significant research progress made by CIMMS scientists at OU and at our NOAA collaborating institutions during the five-year period July 1, 1996-June 30, 2001. -

Lecture 1 UK Weather Lecture 5 UK Weather Is Dominated by The

Lecture 5 Lecture 1 UK weather UK weather is dominated by the passage of low pressure systems (= extratropical cyclones = depressions). The study of mid-latitude weather systems began in earnest when it became possible to take synoptic weather observations. Admiral Robert Fitzroy (1805 - 1865) 1 5.1 The Norwegian cyclone model …a theory explaining the life- cycle of an extra-tropical storm. Idealized life cycle of an extratropical cyclone (2 - 8 days) (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) (f) 2 3 Where do extratropical cyclones form? Hoskins and Hodges (2002) 5.2 Upper-air support Surface winds converge in a low pressure centre and diverge in a high pressure ⇒ must be vertical motion In the upper atmosphere the flow is in geostrophic balance, so there is no friction forcing convergence/divergence. ∴ if an upper level low and surface low are vertically stacked, the surface convergence will cause the low to fill and the system to dissipate. 4 Weather systems tilt westward with height, so that there is a region of upper-level divergence above the surface low, and upper-level convergence above the surface high. 700mb height Downstream of troughs, divergence leads to favorable locations for ascent (red/orange), while upstream of troughs convergence leads to favorable conditions for descent (purple/blue). 5 When upper-level divergence is stronger than surface convergence, surface pressures drop and the low intensifies. When upper-level divergence is less than surface convergence, surface pressures rise and the low weakens. Waves in the upper level flow Typically 3-6 troughs and ridges around the globe - these are known as planetary waves or Rossby waves Instantaneous snapshot of 300mb height (contours) and windspeed (colours) 6 Right now…. -

Turn in Only This Answer Sheet. Keep the Homework Problem Sheets

Earth System Science 5: Homework #6 answer sheet (due 5/29/2008) Name______________________________ Student ID: ____________________ Turn in only this answer sheet. Keep the homework problem sheets. 1) 13) 2) 14) 3) 15) 4) 16) 5) 17) 6) 18) 7) 8) 9) 10) 11) 12) Earth System Science 5: THE ATMOSPHERE / Homework 6 (due 5/29/2008) Name___________________________________ Student ID__________________________________ MULTIPLE CHOICE. Choose the one alternative that best 6) The two major jet streams that impact weather completes the statement or answers the question. in the northern hemisphere are the: 1) Monsoons are most dramatic on this continent: A) polar jet stream and the low-level jet stream. A) Europe. B) Asia. B) polar jet stream and the sub-tropical jet C) North America. D) South America. stream. C) the sub-tropical jet stream and the 2) Ocean currents: low-level jet stream. A) move at a 45 degree angle to the right of D) None of the above. Jet streams are not surface air flow. significant to northern hemisphere B) are driven primarily by differences in weather. ocean temperature over large distances. C) have a much stronger vertical component 7) The subtropical high: than horizontal component. A) has strong winds. D) maintain the same direction at increasing B) often causes dry, desert-like conditions. depth. C) is neither a part of, nor a consequence of, the Hadley cell. 3) The four scales of the atmosphere from largest to smallest are: D) has strong pressure gradients. A) micro, meso, synoptic, planetary. 8) This is NOT a part of the Hadley cell: B) planetary, synoptic, meso, and micro. -

Elemental Geosystems, 5E (Christopherson) Chapter 4 Atmospheric and Oceanic Circulation

Elemental Geosystems, 5e (Christopherson) Chapter 4 Atmospheric and Oceanic Circulation 1) The eruption of Mount Pinatubo in June 1991 A) lofted several million tons of ash, dust, and SO2 into the atmosphere. B) was tracked by AVHRR instruments aboard Earth-orbiting satellites. C) eventually affected almost half the planet after only a few weeks of circulation. D) produced spectacular sunrises and sunsets for almost two years. E) All of these are correct. Answer: E 2) The sulfate particles produced by the eruption of Mount Pinatubo ________ the albedo of the atmosphere, and this ________ the earth. A) increased; warmed B) increased; cooled C) decreased; warmed D) decreased; cooled Answer: B 3) Which of the following refers to primary circulation? A) migratory high and low pressure systems B) the monsoons C) general circulation of the atmosphere D) land-sea breezes Answer: C 4) Which of the following refers to secondary circulation? A) migratory high and low pressure systems B) weather patterns C) general circulation of the atmosphere D) mountain-valley breezes Answer: A 5) Which of the following refers to tertiary circulation? A) migratory high and low pressure systems B) subtropical high pressure systems C) general circulation of the atmosphere D) land-sea breezes Answer: D 6) Air flow is initiated by the A) Coriolis force. B) pressure gradient force. C) friction force. D) centrifugal force. Answer: B 1 7) The horizontal motion of air relative to Earth's surface is A) barometric pressure. B) wind. C) convection flow. D) a result of equalized pressure across the surface. Answer: B 8) Which of the following is not true of the wind? A) It is initiated by the pressure gradient force. -

On the Behavior Patterns of Cyclones and Anticyclones As Related to Zonal Index

VOL. 39, No. 3, MARCH, 1958 149 On the Behavior Patterns of Cyclones and Anticyclones as Related to Zonal Index DOROTHY L. BRADBURY University of Chicago 1 (Manuscript received 19 February 1957) ABSTRACT A statistical study of the variations in the frequency patterns of cyclone and anticyclone centers with respect to the zonal index is described. The results indicate significant variations, especially over the oceans, in the ratio of the frequency of cyclone and anticyclone centers during high-index months to the frequency during low-index months. 1. Introduction five-degree squares was obtained from the Data HE geographical distribution of the fre- Control Division of the Air Weather Service. quency of cyclones and anticyclones has Since the investigation was limited to only the Tbeen investigated by Petterssen (1950). It winter (December, January, February) and sum- was shown that there are certain preferred regions mer (June, July, August) seasons, a total of in the northern hemisphere where the percentage 120 months for each season was considered. The frequency of these centers has pronounced mean monthly sea-level zonal index between 35 maxima and minima. These occur, most gener- and 55°N was computed for each of these months. ally, in connection with certain geographical fea- Then, from each of the two seasons, thirty months tures, such as mountain ranges, bays, inland bodies for which the mean monthly index was nearest of water and coastal configurations. Willett the forty-year seasonal normal were eliminated. (1940) compared the variations in the zonal index The remaining ninety months were then classified with the behavior of some of the principal centers as either high- or low-index according to whether of action, such as the Aleutian Low, Icelandic Low they were above or below the seasonal normal.