Chapter 5 GENERAL CIRCULATION Local Fire-Weather Elements-Wind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

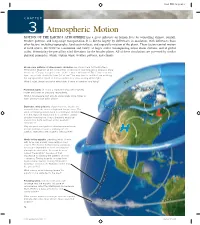

3 Atmospheric Motion

Final PDF to printer CHAPTER 3 Atmospheric Motion MOTION OF THE EARTH’S ATMOSPHERE has a great influence on human lives by controlling climate, rainfall, weather patterns, and long-range transportation. It is driven largely by differences in insolation, with influences from other factors, including topography, land-sea interfaces, and especially rotation of the planet. These factors control motion at local scales, like between a mountain and valley, at larger scales encompassing major storm systems, and at global scales, determining the prevailing wind directions for the broader planet. All of these circulations are governed by similar physical principles, which explain wind, weather patterns, and climate. Broad-scale patterns of atmospheric circulation are shown here for the Northern Hemisphere. Examine all the components on this figure and think about what you know about each. Do you recognize some of the features and names? Two features on this figure are identified with the term “jet stream.” You may have heard this term watching the nightly weather report or from a captain on a cross-country airline flight. What is a jet stream and what effect does it have on weather and flying? Prominent labels of H and L represent areas with relatively higher and lower air pressure, respectively. What is air pressure and why do some areas have higher or lower pressure than other areas? Distinctive wind patterns, shown by white arrows, are associated with the areas of high and low pressure. The winds are flowing outward and in a clockwise direction from the high, but inward and in a counterclockwise direction from the low. -

Climate and Atmospheric Circulation of Mars

Climate and QuickTime™ and a YUV420 codec decompressor are needed to see this picture. Atmospheric Circulation of Mars: Introduction and Context Peter L Read Atmospheric, Oceanic & Planetary Physics, University of Oxford Motivating questions • Overview and phenomenology – Planetary parameters and ‘geography’ of Mars – Zonal mean circulations as a function of season – CO2 condensation cycle • Form and style of Martian atmospheric circulation? • Key processes affecting Martian climate? • The Martian climate and circulation in context…..comparative planetary circulation regimes? Books? • D. G. Andrews - Intro….. • J. T. Houghton - The Physics of Atmospheres (CUP) ALSO • I. N. James - Introduction to Circulating Atmospheres (CUP) • P. L. Read & S. R. Lewis - The Martian Climate Revisited (Springer-Praxis) Ground-based observations Percival Lowell Lowell Observatory (Arizona) [Image source: Wikimedia Commons] Mars from Hubble Space Telescope Mars Pathfinder (1997) Mars Exploration Rovers (2004) Orbiting spacecraft: Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (NASA) Image credits: NASA/JPL/Caltech Mars Express orbiter (ESA) • Stereo imaging • Infrared sounding/mapping • UV/visible/radio occultation • Subsurface radar • Magnetic field and particle environment MGS/TES Atmospheric mapping From: Smith et al. (2000) J. Geophys. Res., 106, 23929 DATA ASSIMILATION Spacecraft Retrieved atmospheric parameters ( p,T,dust...) - incomplete coverage - noisy data..... Assimilation algorithm Global 3D analysis - sequential estimation - global coverage - 4Dvar .....? - continuous in time - all variables...... General Circulation Model - continuous 3D simulation - complete self-consistent Physics - all variables........ - time-dependent circulation LMD-Oxford/OU-IAA European Mars Climate model • Global numerical model of Martian atmospheric circulation (cf Met Office, NCEP, ECMWF…) • High resolution dynamics – Typically T31 (3.75o x 3.75o) – Most recently up to T170 (512 x 256) – 32 vertical levels stretched to ~120 km alt. -

Chapter 9 : Air Mass Air Masses Source Regions

4/29/2011 Chapter 9 : Air Mass • Air masses Contain uniform temperature and humidity characteristics. • Fronts Boundaries between unlike air • Air Masses masses. • Fronts • Fronts on Weather Maps ESS124 ESS124 Prof. Jin-Jin-YiYi Yu Prof. Jin-Jin-YiYi Yu Air Masses • Air masses have fairly uniform temperature and moisture Source Regions content in horizontal direction (but not uniform in vertical). • Air masses are characterized by their temperature and humidity • The areas of the globe where air masses from are properties. called source regions. • The properties of air masses are determined by the underlying • A source region must have certain temperature surface properties where they originate. and humidity properties that can remain fixed for a • Once formed, air masses migrate within the general circulation. substantial length of time to affect air masses • UidilidliliUpon movement, air masses displace residual air over locations above it. thus changing temperature and humidity characteristics. • Air mass source regions occur only in the high or • Further, the air masses themselves moderate from surface low latitudes; middle latitudes are too variable. influences. ESS124 ESS124 Prof. Jin-Jin-YiYi Yu Prof. Jin-Jin-YiYi Yu 1 4/29/2011 Cold Air Masses Warm Air Masses January July January July • The cent ers of cold ai r masses are associ at ed with hi gh pressure on surf ace weath er • The cen ters o f very warm a ir masses appear as sem i-permanentit regions o flf low maps. pressure on surface weather maps. • In summer, when the oceans are cooler than the landmasses, large high-pressure • In summer, low-pressure areas appear over desert areas such as American centers appear over North Atlantic (Bermuda high) and Pacific (Pacific high). -

History of Frontal Concepts Tn Meteorology

HISTORY OF FRONTAL CONCEPTS TN METEOROLOGY: THE ACCEPTANCE OF THE NORWEGIAN THEORY by Gardner Perry III Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1961 Signature of'Author . ~ . ........ Department of Humangties, May 17, 1959 Certified by . v/ .-- '-- -T * ~ . ..... Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Chairman0 0 e 0 o mmite0 0 Chairman, Departmental Committee on Theses II ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The research for and the development of this thesis could not have been nearly as complete as it is without the assistance of innumerable persons; to any that I may have momentarily forgotten, my sincerest apologies. Conversations with Professors Giorgio de Santilw lana and Huston Smith provided many helpful and stimulat- ing thoughts. Professor Frederick Sanders injected thought pro- voking and clarifying comments at precisely the correct moments. This contribution has proven invaluable. The personnel of the following libraries were most cooperative with my many requests for assistance: Human- ities Library (M.I.T.), Science Library (M.I.T.), Engineer- ing Library (M.I.T.), Gordon MacKay Library (Harvard), and the Weather Bureau Library (Suitland, Md.). Also, the American Meteorological Society and Mr. David Ludlum were helpful in suggesting sources of material. In getting through the myriad of minor technical details Professor Roy Lamson and Mrs. Blender were indis-. pensable. And finally, whatever typing that I could not find time to do my wife, Mary, has willingly done. ABSTRACT The frontal concept, as developed by the Norwegian Meteorologists, is the foundation of modern synoptic mete- orology. The Norwegian theory, when presented, was rapidly accepted by the world's meteorologists, even though its several precursors had been rejected or Ignored. -

Weather Numbers Multiple Choices I

Weather Numbers Answer Bank A. 1 B. 2 C. 3 D. 4 E. 5 F. 25 G. 35 H. 36 I. 40 J. 46 K. 54 L. 58 M. 72 N. 74 O. 75 P. 80 Q. 100 R. 910 S. 1000 T. 1010 U. 1013 V. ½ W. ¾ 1. Minimum wind speed for a hurricane in mph N 74 mph 2. Flash-to-bang ratio. For every 10 second between lightning flash and thunder, the storm is this many miles away B 2 miles as flash to bang ratio is 5 seconds per mile 3. Minimum diameter of a hailstone in a severe storm (in inches) A 1 inch (formerly ¾ inches) 4. Standard sea level pressure in millibars U 1013.25 millibars 5. Minimum wind speed for a severe storm in mph L 58 mph 6. Minimum wind speed for a blizzard in mph G 35 mph 7. 22 degrees Celsius converted to Fahrenheit M 72 22 x 9/5 + 32 8. Increments between isobars in millibars D 4mb 9. Minimum water temperature in Fahrenheit for hurricane development P 80 F 10. Station model reports pressure as 100, what is the actual pressure in millibars T 1010 (remember to move decimal to left and then add either 10 or 9 100 become 10.0 910.0mb would be extreme low so logic would tell you it would be 1010.0mb) Multiple Choices I 1. A dry line front is also known as a: a. dew point front b. squall line front c. trough front d. Lemon front e. Kelvin front 2. -

NWS Unified Surface Analysis Manual

Unified Surface Analysis Manual Weather Prediction Center Ocean Prediction Center National Hurricane Center Honolulu Forecast Office November 21, 2013 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Surface Analysis – Its History at the Analysis Centers…………….3 Chapter 2: Datasets available for creation of the Unified Analysis………...…..5 Chapter 3: The Unified Surface Analysis and related features.……….……….19 Chapter 4: Creation/Merging of the Unified Surface Analysis………….……..24 Chapter 5: Bibliography………………………………………………….…….30 Appendix A: Unified Graphics Legend showing Ocean Center symbols.….…33 2 Chapter 1: Surface Analysis – Its History at the Analysis Centers 1. INTRODUCTION Since 1942, surface analyses produced by several different offices within the U.S. Weather Bureau (USWB) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) National Weather Service (NWS) were generally based on the Norwegian Cyclone Model (Bjerknes 1919) over land, and in recent decades, the Shapiro-Keyser Model over the mid-latitudes of the ocean. The graphic below shows a typical evolution according to both models of cyclone development. Conceptual models of cyclone evolution showing lower-tropospheric (e.g., 850-hPa) geopotential height and fronts (top), and lower-tropospheric potential temperature (bottom). (a) Norwegian cyclone model: (I) incipient frontal cyclone, (II) and (III) narrowing warm sector, (IV) occlusion; (b) Shapiro–Keyser cyclone model: (I) incipient frontal cyclone, (II) frontal fracture, (III) frontal T-bone and bent-back front, (IV) frontal T-bone and warm seclusion. Panel (b) is adapted from Shapiro and Keyser (1990) , their FIG. 10.27 ) to enhance the zonal elongation of the cyclone and fronts and to reflect the continued existence of the frontal T-bone in stage IV. -

11 General Circulation

Copyright © 2017 by Roland Stull. Practical Meteorology: An Algebra-based Survey of Atmospheric Science. v1.02 “Practical Meteorology: An Algebra-based Survey of Atmospheric Science” by Roland Stull is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. View this license at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc-sa/4.0/ . This work is available at https://www.eoas.ubc.ca/books/Practical_Meteorology/ 11 GENERAL CIRCULATION Contents A spatial imbalance between radiative inputs and outputs exists for the earth-ocean-atmosphere 11.1. Key Terms 330 system. The earth loses energy at all latitudes due 11.2. A Simple Description of the Global Circulation 330 to outgoing infrared (IR) radiation. Near the trop- 11.2.1. Near the Surface 330 ics, more solar radiation enters than IR leaves, hence 11.2.2. Upper-troposphere 331 there is a net input of radiative energy. Near Earth’s 11.2.3. Vertical Circulations 332 poles, incoming solar radiation is too weak to totally 11.2.4. Monsoonal Circulations 333 offset the IR cooling, allowing a net loss of energy. 11.3. Radiative Differential Heating 334 The result is differential heating, creating warm 11.3.1. North-South Temperature Gradient 335 equatorial air and cold polar air (Fig. 11.1a). 11.3.2. Global Radiation Budgets 336 This imbalance drives the global-scale general 11.3.3. Radiative Forcing by Latitude Belt 338 circulation of winds. Such a circulation is a fluid- 11.3.4. General Circulation Heat Transport 338 dynamical analogy to Le Chatelier’s Principle of 11.4. -

Catastrophic Weather Perils in the United States Climate Drivers Catastrophic Weather Perils in the United States Climate Drivers

Catastrophic Weather Perils in the United States Climate Drivers Catastrophic Weather Perils in the United States Climate Drivers Table of Contents 2 Introduction 2 Atlantic Hurricanes –2 Formation –3 Climate Impacts •3 Atlantic Sea Surface Temperatures •4 El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) •6 North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) •7 Quasi-Biennial Oscillation (QBO) –Summary8 8 Severe Thunderstorms –8 Formation –9 Climate Impacts •9 El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) 10• Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) 10– Other Climate Impacts 10–Summary 11 Wild Fire 11– Formation 11– Climate Impacts 11• El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) & Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) 12– Other Climate / Weather Variables 12–Summary May 2012 The information contained in this document is strictly proprietary and confidential. 1 Catastrophic Weather Perils in the United States Climate Drivers INTRODUCTION The last 10 years have seen a variety of weather perils cause significant insured losses in the United States. From the wild fires of 2003, hurricanes of 2004 and 2005, to the severe thunderstorm events in 2011, extreme weather has the appearance of being the norm. The industry has experienced over $200B in combined losses from catastrophic weather events in the US since 2002. While the weather is often seen as a random, chaotic thing, there are relatively predictable patterns (so called “climate states”) in the weather which can be used to inform our expectations of extreme weather events. An oft quoted adage is that “climate is what you expect; weather is what you actually observe.” A more useful way to think about the relationship between weather and climate is that the climate is the mean state of the atmosphere (either locally or globally) which changes over time, and weather is the variation around that mean. -

Horse Latitudes

HORSE LATITUDES Introduction The Horse Latitudes are located between latitude 30 and latitude 35 north and south of the equator. The region lies in an area where there is a ridge of high pressure that circles the Earth. The ridge of high pressure is also called a subtropical high. Wind currents on Earth, USGS Sailing ships in these latitudes The area between these latitudes has little precipitation. It has variable winds. Sailing ships sometimes while traveling to distant shores would have the winds die down and the area would be calm for days before the winds increased. Desert formation on Earth These warm dry conditions lead to many well known deserts. In the Northern Hemisphere deserts that lie in this subtropical high included the Sahara Desert in Africa and the southwestern deserts of the United States and Mexico. The Atacama Desert, the Kalahari Desert and the Australian Desert are all located in the southern Horse Latitudes. Two explanations for the name There are two explanations of how these areas were named. This first explanation is well documented. Sailors would receive an advance in pay before they stated on a long voyage which was spent quickly leaving the sailors without money for several months while aboard ship. Sailors work off debt When the sailors had worked long enough to again earn enough to be paid they would parade around the deck with a straw-stuffed effigy of a horse. After the parade the sailors would throw the straw horse overboard. Second explanation about horses The second explanation is not well documented. -

Awio20 Fmee 251219 Tropical Cyclone Center / Rsmc La Reunion / Meteo-France

AWIO20 FMEE 251219 TROPICAL CYCLONE CENTER / RSMC LA REUNION / METEO-FRANCE BULLETIN FOR CYCLONIC ACTIVITY AND SIGNIFICANT TROPICAL WEATHER IN THE SOUTHWEST INDIAN OCEAN DATE: 2020/12/25 AT 1200 UTC PART 1: WARNING SUMMARY: Bulletins WTIO22 FMEE n°008/4 and WTIO30 FMEE n°8/4/20202021 issued at 06 UTC on Moderate Tropical Storm CHALANE. Next warnings will be issued at 12 UTC. PART 2 : TROPICAL WEATHER DISCUSSION: The basin remains in a Monsoon Trough (MT) pattern, axed along 10°S. At the western edge, the tropical storm CHALANE is now evolving autonomously with respect to the MT. East of 70°E, in addition to the Area of Disturbed Weather which has been followed for several days but which is in the Indonesian zone, a new area of enhanced low levels vorticity is monitored within the MT southeast of the Chagos archipelago. Moderate tropical storm CHALANE north of the Mascarene Islands: Position at 100 UTC: 16.1°S / 55.3°E Maximum wind over 10 minutes: 35 kt Estimated central pressure: 997 hPa Forward motion: West-Southwestwards at 8 kt For more information, please refer to bulletins WTIO22 and WTIO30 issued at 06Z and followings. Area of Disturbed Weather near the North-Eastern boarder of the basin : An area of vorticity is still present in the Indonesian area around 9S/94E according to the BOM's Tropical Cyclone Outlook for the Western Region (IDW10800). The latest ASCAT swaths show that the surface wind circulation is no longer closed. The minimum is under the influence of a strong easterly shear. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

Ocean Circulation and Climate: a 21St Century Perspective

Chapter 13 Western Boundary Currents Shiro Imawaki*, Amy S. Bower{, Lisa Beal{ and Bo Qiu} *Japan Agency for Marine–Earth Science and Technology, Yokohama, Japan {Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Massachusetts, USA {Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami, Miami, Florida, USA }School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA Chapter Outline 1. General Features 305 4.1.3. Velocity and Transport 317 1.1. Introduction 305 4.1.4. Separation from the Western Boundary 317 1.2. Wind-Driven and Thermohaline Circulations 306 4.1.5. WBC Extension 319 1.3. Transport 306 4.1.6. Air–Sea Interaction and Implications 1.4. Variability 306 for Climate 319 1.5. Structure of WBCs 306 4.2. Agulhas Current 320 1.6. Air–Sea Fluxes 308 4.2.1. Introduction 320 1.7. Observations 309 4.2.2. Origins and Source Waters 320 1.8. WBCs of Individual Ocean Basins 309 4.2.3. Velocity and Vorticity Structure 320 2. North Atlantic 309 4.2.4. Separation, Retroflection, and Leakage 322 2.1. Introduction 309 4.2.5. WBC Extension 322 2.2. Florida Current 310 4.2.6. Air–Sea Interaction 323 2.3. Gulf Stream Separation 311 4.2.7. Implications for Climate 323 2.4. Gulf Stream Extension 311 5. North Pacific 323 2.5. Air–Sea Interaction 313 5.1. Upstream Kuroshio 323 2.6. North Atlantic Current 314 5.2. Kuroshio South of Japan 325 3. South Atlantic 315 5.3. Kuroshio Extension 325 3.1.