DYNAMIC COASTS in a CHANGING CLIMATE Lead Authors: David E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great Maritimes Blizzard of February 18-19, 2004

The Great Maritimes Blizzard of February 18-19, 2004 Chris Fogarty Atlantic Storm Prediction Centre, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia Introduction On 18 February 2004 an intense low pressure system formed well south of Nova Scotia as cold air from eastern North America clashed with the relatively warm waters of the Gulf Stream. The storm moved northeastward passing south of Nova Scotia and over Sable Island. A vast area of heavy snow and high winds swept across Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and southeast New Brunswick bringing blizzard conditions and record snowfalls. Widespread amounts of 60 to 90 cm (24 to 36 inches, 2 to 3 feet) were experienced bringing Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island to a standstill. States of emergency were put into effect across these provinces in order for emergency officials to perform their duties and clean up the mammoth snowfall. It took days for many urban streets and highways to be cleared. 1. The Synoptic Situation A storm track map is shown in Fig. 1 with a time series of minimum sea level pressure in the inset based on analyses at the Maritimes Weather Centre in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The storm formed approximately 200 km southeast of Cape Hatteras, NC at 00 UTC 18 February. It then moved to the northeast at 35-40 km/h, attaining its lowest sea level pressure of 959 mb at 18 UTC 19 February 250 km southeast of Halifax, NS (Fig. 2). Fig. 1. Storm track and time series of minimum sea level pressure. 1 Fig. 2. Sea level pressure analysis of the storm at maximum intensity. -

Planning for Sea-Level Rise in Halifax Harbour Adaptation Measures Can Be Incrementally Adjusted As New Information Becomes Available

i t y i fa x a l P a l h ional Munici eg r Photo courtesy of Planning for sea-level rise in halifax harbour Adaptation measures can be incrementally adjusted as new information becomes available Halifax Regional Municipality (HRM), the capital of Nova Scotia, is Atlantic Canada’s largest city. The municipality covers more than 5500 km2 and has a population of more than 390 000. Halifax Harbour, at the heart of HRM, is a major seaport with significant industrial, military and municipal infrastructure. Rising sea level, along with increased storm intensity and associated waves and storm surges, presents risks to damaging storms residents, property and infrastructure in coastal areas of In recent years, Halifax has experienced frequent extreme HRM. Following extreme weather events in September weather, including several major storms that caused 2003 and February 2004, HRM launched ClimateSMART extensive erosion and flood damage. Most notable was (Sustainable Mitigation & Adaptation Risk Toolkit) to help Hurricane Juan in September 2003, a “once-in-a-century” mainstream climate change mitigation and adaptation into event. This Category 2 hurricane made landfall just west municipal planning and decision making. ClimateSMART of Halifax and tracked across central Nova Scotia and initiated discussion of climate change and spurred further Prince Edward Island, leaving a trail of damage to property, adaptation action. infrastructure and the environment (cost estimated at In August 2006, the HRM Council adopted the Regional $200 million). A few months later, in February 2004, the Municipal Planning Strategy, an integrated land use severe winter blizzard that became known as “White Juan” planning guide for future development. -

Examining the Effect of Visualization Tool Exposure on Local-Level Stakeholder Perceptions on Climate Change Adaptation

Examining the Effect of Visualization Tool Exposure on Local-level Stakeholder Perceptions on Climate Change Adaptation by Maliha Majeed A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Environmental Studies in Geography Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2015 © Maliha Majeed 2015 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT Vulnerabilities of human communities, driven by environmental, social, economic, and political dynamics, vary across geographical and social regions. Coastal communities are considered to be among those greatest at risk from climate impacts. To cope with these impacts, communities must assess existing vulnerabilities and adaptive capacities, and begin to adapt. Currently, community-based research often focuses on identifying vulnerabilities and possible adaptations, but rarely examines how local-level stakeholders perceive adaptation-based needs and potential action. This research study focuses on Lennox Island, in Prince Edward Island and the Town of Lockeport, in Nova Scotia to examine how two innovative visualization tools, CLIVE and AdaptNS, influence stakeholder perceptions on climate change adaptation. This study explores whether tool exposure changes perceptions of awareness and priorities for potential action among local-level decision-makers and stakeholders. It further explores which aspects of the visualization tools resonate among local-level decision-makers. This research builds on existing vulnerability assessment information established through the Partnership for Canada-Caribbean Community Climate Change Adaptation (ParCA) research project and uses a methodological approach involving semi-structured interviews and community-based workshops with local-level decision-makers and community stakeholders, respectively. -

Bringing Adaptation Home: Citizen Engagements with Climate Change at Home Site Scales in Ottawa and Halifax

Bringing adaptation home: Citizen engagements with climate change at home site scales in Ottawa and Halifax by Magdalene Goemans A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2018 Magdalene Goemans ABSTRACT Climate change impacts are becoming increasingly evident in cities, generating hazards such as heatwaves and flooding events that may cause discomfort or trauma for residents. Climate change scholars suggest that measures undertaken on private lands provide a significant counterpart to public adaptation initiatives, and increasingly position the home site as an important scale of analysis within climate change research (Bichard & Kazmiercak, 2009; Jeffers, 2014; Pyhala et al., 2016; Wilson et al., 2014). Select scholars have also considered how municipalities may effectively engage with citizens to encourage greater home-based responses to climate-related hazards (Groulx et al., 2014; Hjerpe et al., 2014; Klein, 2014). This thesis explores citizen perspectives of climate change impacts, risk and opportunities for adaptation that are based at the scale of the urban home site in two mid- sized Canadian cities, Ottawa and Halifax. Through a qualitative research approach of discourse analysis, this thesis explores several distinct but related sub-themes: (1) how residents understand local places of climate change impacts and risk; (2) how residents engage with home site natures within -

Registration Document, November 2005, Was Followed to Determine Potential Species of Concern for the Project Site

Contents Chapter 1 Introduction ...............................................................................................1 1.1 Registration Requirements ..................................................................................................1 1.2 Proponent Information ........................................................................................................1 1.2.1 Business Principles and Policies.............................................................................3 1.3 Context and Background.....................................................................................................5 1.3.1 Historic Coal Mining in Sydney Coal Field............................................................5 1.3.2 Exploration Agreement and License.......................................................................6 1.4 The Project ..........................................................................................................................7 1.4.1 Project Location and the Resource Block ...............................................................7 1.4.2 Land Holdings.........................................................................................................8 1.4.3 Project Parameters ..................................................................................................8 1.4.4 Existing and Proposed Site Infrastructure...............................................................9 1.4.5 Completion of Tunnel Dewatering .........................................................................9 -

Chapter 8: Atlantic Canada

8 · Atlantic Canada CHAPTER 8: ATLANTIC CANADA LEAD AUTHORS: ERIC RAPAPORT1 SIDNEY STARKMAN2 WILL TOWNS3 CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS: NORM CATTO (MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NEWFOUNDLAND), SABINE DIETZ (GOVERNMENT OF NEW BRUNSWICK), KEN FORREST (CITY OF FREDERICTON), CHRIS HALL (PORT OF SAINT JOHN), JEFF HOYT (GOVERNMENT OF NEW BRUNSWICK), DON LEMMEN (NATURAL RESOURCES CANADA), SHAWN MACDONALD (GOVERNMENT OF NOVA SCOTIA), TYLER O’ROURKE (PORT OF SAINT JOHN), BOB PETT (NOVA SCOTIA INTERNAL SERVICES), YURI YEVDOKIMOV (UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK) RECOMMENDED CITATION: Rapaport, E., Starkman, S., and Towns, W. (2017). Atlantic Canada. In K. Palko and D.S. Lemmen (Eds.), Climate risks and adaptation practices for the Canadian transportation sector 2016 (pp. 218-262). Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada. 1 School of Planning, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS 2 School of Planning, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS 3 School of Planning, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON and Transport Canada, Ottawa, ON Climate Risks & Adaptation Practices - For the Canadian Transportation Sector 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Key Findings .......................................................................................................................................................220 1.0 Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................221 1.1 Environmental characteristics ........................................................................................................221 -

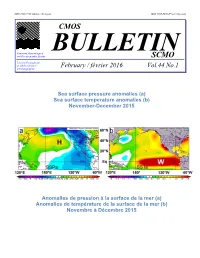

CMOS Bulletin SCMO Volume 44 No. 1 February 2016

ISSN 1929-7726 (Online / En ligne) ISSN 1195-8898 (Print / Imprimé) CMOS Canadian Meteorological BULLETIN and Oceanographic Society SCMO La Société canadienne de météorologie et February / février 2016 Vol.44 No.1 d'océanographie Sea surface pressure anomalies (a) Sea surface temperature anomalies (b) November-December 2015 Anomalies de pression à la surface de la mer (a) Anomalies de température de la surface de la mer (b) Novembre à Décembre 2015 Canadian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society Société canadienne de météorologie et d’océanographie .... Words from the President CMOS Bulletin SCMO Friends and Colleagues: Volume 44 No.1 February 2016 — février 2016 The year 2016 promises to be an Inside / En Bref exciting one for Words from President Martha Anderson page 1 CMOS. The Congress in Cover page / page couverture page 2 Fredericton, N.B. will be our 50th Allocution de la présidente congress! We hope Martha Anderson page 3 many of you will be there. The joint Articles congress with the Canadian Delayed El Niño impacts in the Northeast Geophysical Union Pacific Ocean? by William Crawford page 5 (CGU) has the Presenting the City of Edmonton Weather Radar theme of “Monitoring by Daniel Jobin, Christian Jacques, of and Adapting to and Steven Chan page 9 Extreme Events and Martha Anderson Long-Term CMOS President 2015 likely to be Warmest on Record; Présidente de la SCMO Variations”. 2011-2015 Warmest Five Year Period page 10 Through 2016, we will be preparing for the larger milestone Canada's Top Ten Weather Stories for 2015 in 2017, the 50th anniversary of the creation of the Canadian by David Phillips page 16 Meteorological Society in 1967, and the addition of the oceanographic disciplines in 1977. -

Incorporating Climate Resilience for Municipal Infrastructure Into the Updates of Existing Atlantic Canada Water and Wastewater Design Guidelines

Incorporating Climate Resilience for Municipal Infrastructure into the Updates of Existing Atlantic Canada Water and Wastewater Design Guidelines Led by: Atlantic Canada Water and Wastewater Association Consultant: CBCL Limited Peer Review: exp ACWWA Halifax 2019 Conference October 08, 2019 | Willard D’Eon, MPH, P.Eng. Update the ACWWA Water Incorporate the design Supply Guidelines and of climate resilient ACWWA Wastewater infrastructure Guidelines Project RFP issued by Awarded to CBCL ACWWA on March 14, 2019 February 06, 2019 Project Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) under the: Building Regional BRACE Adaptation Capacity and Expertise program Project Funding 5 Year (2017-2022) $18 m 18 programs under program current funding To increase the ability of 8 in Atlantic Canada communities, organizations… to access, use and apply knowledge and tools on climate change adaptation in their work. BRACE program Atlantic Canada funded projects: Government of NS $1,000,000 Government of PEI $1,000,000 Government of NL $ 909,000 NB Environmental Network $ 421,000 NB Fed. of Woodlot Owners $ 361,000 ACWWA Guidelines Updates $ 318,000 University de Moncton $ 235,000 Memorial University $ 122,000 BRACE program Internal presentations to BRACE in June 2019 on 5 projects ACWWA, Memorial U , U de M, plus two from Saskatchewan Participant noted that we are doing “Climate Change 101” across the county National Conferences will be key to achieve uniformity BRACE Presentation Four Project Committee meetings Three drafts plus final Guidelines Four workshops (one in each AC province) Presentations at two national conferences Adaptation Canada 2020, Vancouver, February: approved for Joint poster session with Memorial University, and Workshop CWWA November 2020 Presentation at two local conferences Non-technical Webinar Project Deliverables Water Supply Lead: Halifax Water (Owners): Wendy Krkosek, B.A.Sc., Ph.D., P.Eng. -

Prince Edward Island Annual Climate Summary 2016

Climate Research Lab Prince Edward Island Annual Climate Summary 2016 Figure 1–Storm Surge, North Rustico, November 27, 2016 Background The UPEI Climate Research Lab is in the process for establishing a meso-network of climate stations located in key locations across the province. This can help reduce model uncertainties in temperature and precipitation variances and to provide reference ground truth data to aid in the evaluation of climate model simulations and to enable assessment of micro-climate environments in the province. More localized data from these stations will be of assistance to those who depend on high quality climate data to make more informed decisions. In 2016 the UPEI Climate Research Lab expanded its network of climate monitoring stations by adding 3 new stations in geographic areas without a pre-existing climate station. The first one is a new UPEI station located at Acadian Machine Works in Tignish (UP18) and is equipped with Davis Vantage Pro 2 plus equipment which has instrumentation to measure temperature, precipitation, barometric pressure, relative humidity, wind direction, wind speed, solar radiation and UV Index. Two new private stations were also added to the network. The first one is at an organic vegetable farm at Hope River (UP19) and the second is at a residential home and observatory located at Mill Cove (UP20). The data collected is being compiled in a database called COADE, which in addition to climate data also stores coastal erosion and tide logger data. This database is not yet available to the public. Table 1 – UPEI Climate Lab Climate Stations including some PEI Dept. -

Using an EMO-Based Hazard Risk Vulnerability Assessment Process for Municipal Climate Change Action Plan Development

Using an EMO-Based Hazard Risk Vulnerability Assessment Process for Municipal Climate Change Action Plan Development Town of Truro and County of Colchester March 2013 In completion of a grant from the Nova Scotia Climate Change Directorate, Climate Change Adaptation Fund For: Town of Truro & County of Colchester HRVA-MCCAP Core Working Group Prepared by: Elemental Sustainability Consulting Ltd. Anne Warburton and HMC/EMC Inc. Heather MacKenzie-Carey Climate Change Adaptation Fund: HRVA-MCCAP Project Final Report 2013 2 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 PROJECT BACKGROUND 6 HRVA WORK SESSIONS 8 HRVA RESULTS SUMMARY 9 KEY LESSONS 14 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR HRVA USE FOR MCCAP DEVELOPMENT 16 APPENDIX A: COMPLETED HAZARD RISK VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENTS 21 APPENDIX B: WHITE FLAGS, RED STOPS, GREEN STOPS 22 Climate Change Adaptation Fund: HRVA-MCCAP Project Final Report 2013 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Nova Scotia Climate Change Directorate’s Climate Change Adaptation Fund awarded funding to the Town of Truro and County of Colchester to explore the benefits and limitations of using an emergency management based risk assessment process during municipal climate change action planning. This report: • reviews the approach taken to infuse an emergency management process into municipal climate change action plan (MCCAP) development, • summarizes the strengths and limitations that were revealed during the process, • discusses ways in which municipal and emergency management perspectives converge and diverge in the context of climate change action planning, and • provides recommendations for other municipalities or organizations interested in using an emergency management based hazard risk vulnerability assessment (HRVA) for informing climate adaptation priorities and actions. The project was premised on the hypothesis that using the HRVA tool, which is a collaborative planning process, would improve the thoroughness and accuracy of both HRVA and MCCAP content while simultaneously fostering improved communication / data sharing between municipal planners and EMO professionals. -

Town Council Tuesday, November 12, 2013 6:30 P.M

Town Council Tuesday, November 12, 2013 6:30 p.m. Council Chambers, Town Hall 359 Main Street Agenda 1. Approval of the Agenda 2. Approval of the Minutes of October 29, 2013 (attached) 3. Presentation a. Robert Stead – Public Art 4. Reports a. Mayor b. Chief Administrative Officer 5. Information a. Design Review Committee – RFD #060-2013 (attached) 6. Decisions a. Unsightly Premises at 23 Highland Ave. – RFD #59-2013 (attached) b. Municipal Climate Change Action Plan – RFD #057-2013 (attached) c. Appointment of Auditor – RFD #058-2013 (attached) 359 Main Street | Wolfville | NS | B4P 1A1 | t 902-542-5767 | f 902-542-4789 Wolfville.ca 7. Question Period Procedure: A thirty minute time period will be provided for members of the public to address Council regarding questions, concerns and/or ideas. Each person will have a maximum of two minutes to address Council with a second two minute time period provided if there is time remaining within the thirty minute Public Input/Question Period timeframe. 8. Adjourned to In Camera Session 9. In Camera Session: Personnel 10. In Camera Session Adjourned 11. Regular Session Reconvened 12. Reports from In Camera Session 13. Adjournment of Regular Session 359 Main Street | Wolfville | NS | B4P 1A1 | t 902-542-5767 | f 902-542-4789 Wolfville.ca Art in Public Spaces for Wolfville. A proposal to Council by Robert Stead; immediate past mayor Purpose The purpose of this presentation is to: 1. Convince Council of the benefits of a regular program of installing juried art in public places in Wolfville, 2. Urge Council to develop a policy to govern a program of art in public places with a view of placing a first installation in 2016. -

FMC History Fr 1971 (Cover)

Fort Massey United Church Entering a Second Century of Witness 1971-2011 Ruth MacKenzie, M.D ©2011 by Fort Massey United Church www.fortmasseychurch.com 5303 Tobin Street, Halifax, NS B3H 1S3 902-423-4294 [email protected] Cover: Watercolour by J. Mont, living on-the-street Given in appreciation to Fort Massey For being there for him. FORT MASSEY UNITED CHURCH ENTERING A SECOND CENTURY OF WITNESS FORT MASSEY UNITED CHURCH 1971-2011 CONTENTS Introduction .….…………………….…..…..…2 Clergy .….………….…………..………..3 Spiritual .…………………………………..5 Outreach …………………………………...9 Communication …….....…………………………..9 Music at The Fort ………………...………………..10 The Fort Massey Family ……………...…………………..12 The Youth ……………...…………………..12 Special People ……………...…………………..13 Building ...………………………………..15 Annexes: A.1 Elders and clerks of Kirk Session ……………...…………………18 A.2 Directors of Music ...……...………………………19 A.3 Secretaries ..……...…………………………………19 A.4 Fort Massey Ordinands …...……...……………………………20 A.5 Anniversary preachers/speakers ..……...………………………20 A.6 Presidents of the UCW …...……...…………..………24 A.7 Presidents of the UC Men …...……...…………………..24 A.8 Wm S Fong Volunteer of the Year recipients …...……...……..24 A.9 Chairs of Board of Management ...……...…………………..25 A.10 Scout/Cubmasters — 18th Boy Scout/Cub Troop ...……...……...26 A.11 Sunday School Superintendents .……...……………………...26 A.12 Trustees ...……...……………………..27 A.13 Gifts and memorials ...……...……………………...27 A.14 Use of the building .……...……………………...31 A.15 Order of Fort Massey Recipients ...……...……………………...32 A.16 Junior Choir picture — 1984 ...……...………………………32 B. Historical Data ..……...………………………………..33 INTRODUCTION In 1971, Fort Massey United Church, under the auspices of the Centenary Committee1, celebrated her Centennial in the following manner: 1. an Anniversary Dinner on December 10; 2. a 100th Anniversary service (Centennial) on December 12 with Rev.