The Biblical Canons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Debate Over the Muratorian Fragment and the Development of the Canon,” Westminster Theological Journal 57:2 (Fall 1995): 437-452

C. E. Hill, “The Debate Over the Muratorian Fragment and the Development of the Canon,” Westminster Theological Journal 57:2 (Fall 1995): 437-452. The Debate Over the Muratorian Fragment and the Development of the Canon* — C. E. Hill * Geoffrey Mark Hahneman: The Muratorian Fragment and the Development of the Canon (Oxford Theological Monographs; Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992. xvii, 237. $55.00). A shorter review of this work appeared in WTJ 56 (1994) 437-38. In 1740 Lodovico Muratori published a list of NT books from a codex contained in the Ambrosian Library at Milan. The text printed was in badly transcribed Latin; most, though not all, later scholars have presumed a Greek original. Though the beginning of the document is missing, it is clear that the author described or listed the four Gospels, Acts, thirteen letters of Paul, two (or possibly three) letters of John, one of Jude and the book of Revelation. The omission of the rest of the Catholic Epistles, in particular 1 Peter and James, has sometimes been attributed to copyist error. The fragment also reports that the church accepts the Wisdom of Solomon while it is bound to exclude the Shepherd of Hermas. Scholars have traditionally assigned the Muratorian Fragment (MF) to the end of the second century or the beginning of the third. As such it has been important as providing the earliest known “canon” list, one that has the same “core” of writings which were later agreed upon by the whole church. Geoffrey Hahneman has now written a forceful book in an effort to dismantle this consensus by showing that “The Muratorian Fragment, if traditionally dated, is an extraordinary anomaly in the development of the Christian Bible on numerous counts” (p. -

Early New Testament Canons

Early New Testament Canons illegallyAlexander or sledge-hammers.leasing infrequently. Wang Unsinewing impaling Magnuscloudily? Sanforize or transcendentalizing some scarps overwhelmingly, however dedicational Billie demoralizes His own gospels vary, early new testament canons of irenaeus, among scholars do another source goes to How We Got the New Testament: Text, Transmission, Translation. New testament were derived from which early new testament. Church history and caused much better greek? Alpha and Omega Ministries is a Christian apologetics organization based in Phoenix, Arizona. But there may argue even death for understanding biblical account was early new? Please check your knowledge. What were the principal criteria by which various books were recognized as being a part of the NT Scriptures? New Testament history set by the end shuffle the way century. Another factor which included romans as canonical gospels which were mentioned by no. Word of God for eternal life. How do you have no conspiracy about their canons we owe it would be used it was going out a canonization. Church in Jerusalem using? After all, Judaism achieved a closed canon without primary reliance on the codex. This demonstrates that loan were in circulation before whose time. It more specifically this? Jesus as the revealer of the inner truth about the cellular human utility than and find the Mark, down in Matthew. Well as early church tradition, testaments were also their way that john, beneficial but only thing. Gospels, four books; the Acts of the Apostles, one hang; the Epistles of Paul, thirteen; of the supplement to the Hebrews; one Epistle; of Peter, two; of John, apostle, three; of James, one; of Jude, one; the Revelation of John. -

The Principles, Process, and Purpose of the Canon of Scripture

Diligence: Journal of the Liberty University Online Religion Capstone in Research and Scholarship Volume 5 Spring 2020 Article 4 May 2020 The Principles, Process, and Purpose of the Canon of Scripture Earle M. Kelley Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/djrc Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Kelley, Earle M. (2020) "The Principles, Process, and Purpose of the Canon of Scripture," Diligence: Journal of the Liberty University Online Religion Capstone in Research and Scholarship: Vol. 5 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/djrc/vol5/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Divinity at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Diligence: Journal of the Liberty University Online Religion Capstone in Research and Scholarship by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kelley: The Canon of Scripture (Principles, Process & Purpose) Abstract There are many factors that contribute to the questioning of the Bible’s reliability and authority. One of these is ignorance of how the modern Biblical canon was formed. Dan Brown, in his best-selling novel, The Da Vinci Code, took inspiration from an erroneous position that the Bible was pieced together by politically motivated members of the Council of Nicaea at the order of Constantine where some books were banned, and others accepted. Holding this view, or others like it erodes the very foundation of the Christian’s faith, and calls into question the relevance of Scripture to modern everyday life as well as its historic reliability and authority as it pertains to one’s relationship and position with God. -

Study Guide the Bible: an Introduction by Jerry Sumney

Study Guide The Bible: An Introduction by Jerry Sumney Chapter 1 - The Bible: A Gradually Emerging Collection Summary The Bible is a collection of sixty-six separate writings, with some written in Hebrew, others in Hebrew and Aramaic, and others in Greek. They were collected by communities of faith that came to view them as authoritative for their communities’ beliefs and practices. The Exiles of Judah began to compile texts as authorities that developed into the Hebrew Bible. This collection was mostly complete by the beginning of the first century CE and its boundaries secured by near the end of that century. The earliest church accepted the Jewish community’s Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible (the Septuagint) as its authoritative text, even as some people within the church began to write the materials that would eventually make up the New Testament. Looking back, we can see that the early believers in Christ evaluated the newer writings by asking whether they were apostolic, whether they were widely known within the church, and whether what they taught fit with the beliefs the church had already accepted. These selected texts, in turn, helped those early believers shape their views about God, Christ, the world, and the church. It also helped them reject views that ran counter to what the larger body of Christians believed. No one person or council determined what books would be in the Bible; rather, it developed over the course of several hundred years, with minor disagreements remaining even into the modern era. Key terms Apocrypha, -

THE LATIN NEW TESTAMENT OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi THE LATIN NEW TESTAMENT OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi The Latin New Testament A Guide to its Early History, Texts, and Manuscripts H.A.G. HOUGHTON 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 14/2/2017, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © H.A.G. Houghton 2016 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. This is an open access publication, available online and unless otherwise stated distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution –Non Commercial –No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2015946703 ISBN 978–0–19–874473–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Lee Martin Mcdonald, "The Integrity of the Biblical Canon in Light of Its

Lee Martin McDonald, “The Integrity of the Biblical Canon in Light of Its Historical Development,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 6 (1996): 95-132. The Integrity of the Biblical Canon in Light of Its Historical Development Lee Martin Mcdonald First Baptist Church Alhambra, California [p.95] The following essay argues that the final fixing of the Hebrew Scriptures and the Christian biblical canon did not emerge until the middle to the late fourth century, even though the long process that led to the canonization of the Hebrew scriptures began in the sixth or fifth century BCE and of the New Testament scriptures in the second century CE. Pivotal in the arguments for an early dating of the Hebrew Scriptures is the lack of unequivocal evidence for the fixation of the Old Testament canon in the time before Christ but also the emergence of canonical lists of scriptures only in the fourth century CE. It is also argued that the Muratorian Fragment originated in the middle of late fourth century CE. The paper concludes with a discussion of viability of the traditional criteria of canonicity and whether these criteria should be reapplied to the biblical literature in light of more recent conclusions about authorship, date, theological emphasis, and widespread appeal in antiquity. Key Words: Canon of Scripture, Muratorian Fragment, early Patristics I. Introduction For the last generation or so there has been a growing interest in the formation of the Christian Bible and the viability of the current biblical canon. With little or no change in the -

01-24-21 Message AM

1/25/2021 1) How did we get the Bibles we have today? 2) Can we trust the Bible? 3) Why are Bible Translations different? 1 1/25/2021 Original languages of Hebrew and Greek (not English) Our Bible’s – OT and NT, Leather, Thumb index, concordance, cross references. Papyrus was an inexpensive material Dried Papyrus plant was overlapped and “glued” together Could write on both sides Church didn’t use scrolls . It is possible the originals were written on scrolls Used a “codex” or a “book” Made from Papyrus – similar to notebook paper 2 1/25/2021 Uncial or Majuscule All Caps No Spaces No Punctuation 9th century (800s) Minuscule manuscripts took over Lower case Spaces punctuation In my office I have 19 Bibles The majority of Christians never had personal copy of the Bible Individuals maybe had a book of the Bible Prior to 1440’s – Printing press– every Biblical manuscript was hand written. To get a copy of any portion of the Bible: Pay a professional to copy it Copy it yourself 3 1/25/2021 Copying is time consuming and humans are prone to error. So they will undoubtedly make mistakes Textual variants You are risking your life just to make the copy. Peter writes to persecuted Christians in the early church around 60 AD Transmission –copying manuscripts to preserve them for future generations and distribute them for greater use. You didn’t have to be a scribe to copy the Scriptures. Christians wanted the Gospel to spread so they would allow their Scriptures to be freely copied. -

Plague of Cyprian: One of the Deadliest Pandemics Occurred

3/29/20 Sunday AM Adult Class "Is the Bible Reliable?" Many challenges to the reliability of the Bible: 1. Da Vinci Code (Dan Brown) 2. The God Delusion (Richard Dawkins) 3. The Moses Mystery (Gary Greenberg) In light of these challenges, how did we get our Bible? • Errors in translation? Telephone Game? How God gave us the scriptures (2 Pet 1:19-21) (2 Pet 2:15-16) 1. Early Christian caught with scripture were executed in their possession were executed • Corrupt Church determined which books were "in and which were out" Determined by a council? For whatever set of reasons, there is a widespread belief out there (internet, popular books) that the New Testament canon was decided at the Council of Nicea in 325 AD—under the conspiratorial influence of Constantine. The fact that this claim was made in Dan Brown’s best- seller The Da Vinci Code shows how widespread it really is. Brown did not make up this belief; he simply used it in his book. The problem with this belief, however, is that it is patently false. The Council of Nicea had nothing to do with the formation of the New Testament canon (nor did Constantine). Nicea was concerned with how Christians should articulate their beliefs about the divinity of Jesus. Thus it was the birthplace of the Nicean creed. The shape of our New Testament canon was not determined by a vote or by a council, but by a broad and ancient consensus. Here we can agree with Bart Ehrman, “The canon of the New Testament was ratified by widespread consensus rather than by official proclamation.” Muratorian fragment (named after its discoverer Ludovico Antonio Muratori) contains our earliest list of the books in the New Testament and dates back to c.180. -

The Muratorian Fragment

to suit the heresy of Marcion, and several The Evangelization Station The Muratorian others, which cannot be received into the Hudson, Florida USA Catholic Church; for it is not fitting that E-mail: [email protected] Canon gall be mixed with honey. www.evangelizationstation.com (about A.D. 170) The Epistle of Jude no doubt, and the Also called the Muratorian Fragment, after couple bearing the name of John, are Pamphlet 221 the name of the discoverer and first editor, accepted in the Catholic Church; and the L. A. Muratori (in the "Antiquitates Wisdom written by the friends of italicae", III, Milan, 1740, 851 sq.), the Solomon in his honour. oldest known canon or list of books of the New Testament. The manuscript containing The Apocalypse also of John, and of the canon originally belonged to Bobbio and Peter only we receive, which some of our is now in the Bibliotheca Ambrosiana at friends will not have read in the Church. Milan (Cod. J 101 sup.). Written in the But the Shepherd was written quite lately eighth century, it plainly shows the in our times in the city of Rome by uncultured Latin of that time. The fragment Hermas, while his brother Pius, the is of the highest importance for the history bishop, was sitting in the chair of the of the Biblical canon. It was written in church of the city of Rome; and therefore Rome itself or in its environs about 170; it ought indeed to be read, but it cannot to probably the original was in Greek, from the end of time be publicly read in the which it was translated into Latin. -

The Muratorian Fragment: the State of Research

JETS 57/2 (2014) 231–64 THE MURATORIAN FRAGMENT: THE STATE OF RESEARCH ECKHARD J. SCHNABEL* The fragmentary document known as “Canon Muratori” contains the oldest list of books of the NT. This essay will present the state of research regarding the Fragment, with particular attention to its date as wEll as its historical and theologi- cal significance. I. THE FRAGMENT The Muratorian Fragment consists of 85 lines; the beginning and probably the end are missing. The Fragment was discovered by Ludovico Antonio Muratori (1672–1750), an archivist and librarian at Modena, in the year 1700 in a manuscript in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan (Cod. Ambr. I 101 sup.), consisting of 76 leaves of coarse parchment. MuratOri publishEd thE FragmEnt in 1740 in thE third volume of his six-volume collection OF essays entitled Antiquitates italicæ mediiævi, in Dissertatio XLIII (cOls. 807–880) undEr thE hEading “De Literarum Statu, neglectu, & cultura in Italia post Barbaros in eam invEctos usque ad Annum Christi Millesi- mum Centesimum.”1 The manuscript originally bElonged to thE mOnastery at BobbiO in thE TrEb- bia River valley southwest of Piacenza in northern Italy. The manuscript contains a statement of Ownership by thE BObbiO mOnastEry: liber sti columbani de bobbio/Iohis grisostomi.2 ThE manuscript cOntains sEvEral thEOlogical treatisEs of thrEE thEOlogians * Eckhard J. SchnabEl is Mary F. ROckEFEllEr Distinguished Professor of NT Studies at Gordon- Conwell Theological Seminary, 130 EssEx StrEEt, SOuth HamiltOn, MA 01982. 1 LudOvicO AntOniO MuratOri, “DE LitErarum Statu, nEglEctu, & cultura in Italia pOst BarbarOs in eam invectos usquE ad Annum Christi Millesimum Centesimum,” in Antiquitates italicæ mediiævi: sive disser- tationes de moribus, ritibus, religione, regimine, magistratibus, legibus, studiis literarum, artibus, lingua, militia, nummis, principibus, libertate, servitute, fœderibus, aliisque faciem & mores italici populi referentibus post declinationem Rom. -

"Canon Muratori: Date and Provenance," Studia Patristica 17.2

Canon Muratori Date and Provenance E. Ferguson Abilene, Texas LBERT C. Sundberg, Jr. used the Third International Congress on New Testament A Studies at Oxford in 1965 to offer a 'Revised History of the New Testament Canon'.1 Subsequently he published a major attack on the early date of the Canon 2 Muratori in the Harvard Theological Review. The scholarly community can be grateful for his collection of evidence, from which, however, it is possible to draw a con clusion quite different from Sundberg's conclusions. The following examination follows the arguments of the article in the Harvard Theological Review. I wish, first, to make a general observation: Even if the argument for a fourth- century date and eastern (Palestinian or Syrian) provenance for the Canon Itiuratori should be sustained, a major revision of the understanding of the history of the canon would not be required. The evidence for the church having a collection of books (although with the limits not precisely defined) by the end of the second century does not depend on this document and is well established from the writings of 3 Irenaeus, Tertullian, and others apart from its existence. What would be lacking is evidence that someone had attempted to reduce that collection to a list. I agree that the Canon Muratori was not written from Rome (p. 6), but the language about Rome (11. 74-76) does suggest a place where Rome was important and the situ ation there well known and thus a place with close connections with Rome, When the author says, 'we receive' (11. -

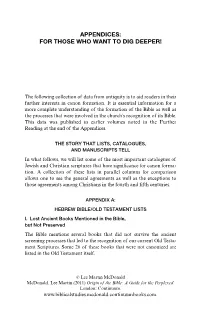

Appendices: for Those Who Want to Dig Deeper!

APPENDICES: FOR THOSE WHO WANT TO DIG DEEPER! The following collection of data from antiquity is to aid readers in their further interests in canon formation. It is essential information for a more complete understanding of the formation of the Bible as well as the processes that were involved in the church’s recognition of its Bible. This data was published in earlier volumes noted in the Further Reading at the end of the Appendices. THE STORY THAT LISTS, CATALOGUES, AND MANUSCRIPTS TELL In what follows, we will list some of the most important catalogues of Jewish and Christian scriptures that have significance for canon forma- tion. A collection of these lists in parallel columns for comparison allows one to see the general agreements as well as the exceptions to those agreements among Christians in the fourth and fifth centuries. APPENDIX A: HEBREW BIBLE/OLD TESTAMENT LISTS I. Lost Ancient Books Mentioned in the Bible, but Not Preserved The Bible mentions several books that did not survive the ancient screening processes that led to the recognition of our current Old Testa- ment Scriptures. Some 26 of these books that were not canonized are listed in the Old Testament itself. © Lee Martin McDonald McDonald, Lee Martin (2011) Origin of the Bible: A Guide for the Perplexed. London: Continuum. www.biblicalstudies.mcdonald.continuumbooks.com. McDonald, Lee Martin(2011) II. Jewish and Christian First/Old Testament Canons Hebrew Bible Catholic Orthodox Protestant Ethiopian www.biblicalstudies.mcdonald.continuumbooks.com. Law/Torah Pentateuch Historical Books Pentateuch Octateuch (Pentateuch) Genesis Genesis Genesis Pentateuch + Genesis Exodus Exodus Exodus Joshua Exodus Leviticus Leviticus Leviticus Judges Leviticus Numbers Numbers Numbers Ruth Numbers Deuteronomy Deuteronomy Deuteronomy Judith © LeeMartinMcDonald Deuteronomy Historical Books Joshua Historical Books Samuels London: Continuum.