Lee Martin Mcdonald, "The Integrity of the Biblical Canon in Light of Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Debate Over the Muratorian Fragment and the Development of the Canon,” Westminster Theological Journal 57:2 (Fall 1995): 437-452

C. E. Hill, “The Debate Over the Muratorian Fragment and the Development of the Canon,” Westminster Theological Journal 57:2 (Fall 1995): 437-452. The Debate Over the Muratorian Fragment and the Development of the Canon* — C. E. Hill * Geoffrey Mark Hahneman: The Muratorian Fragment and the Development of the Canon (Oxford Theological Monographs; Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992. xvii, 237. $55.00). A shorter review of this work appeared in WTJ 56 (1994) 437-38. In 1740 Lodovico Muratori published a list of NT books from a codex contained in the Ambrosian Library at Milan. The text printed was in badly transcribed Latin; most, though not all, later scholars have presumed a Greek original. Though the beginning of the document is missing, it is clear that the author described or listed the four Gospels, Acts, thirteen letters of Paul, two (or possibly three) letters of John, one of Jude and the book of Revelation. The omission of the rest of the Catholic Epistles, in particular 1 Peter and James, has sometimes been attributed to copyist error. The fragment also reports that the church accepts the Wisdom of Solomon while it is bound to exclude the Shepherd of Hermas. Scholars have traditionally assigned the Muratorian Fragment (MF) to the end of the second century or the beginning of the third. As such it has been important as providing the earliest known “canon” list, one that has the same “core” of writings which were later agreed upon by the whole church. Geoffrey Hahneman has now written a forceful book in an effort to dismantle this consensus by showing that “The Muratorian Fragment, if traditionally dated, is an extraordinary anomaly in the development of the Christian Bible on numerous counts” (p. -

The Origin of the New Testament by Adolf Harnack About the Origin of the New Testament by Adolf Harnack

The Origin of the New Testament by Adolf Harnack About The Origin of the New Testament by Adolf Harnack Title: The Origin of the New Testament URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/harnack/origin_nt.html Author(s): Harnack, Adolf (1851-1930) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Rights: Public Domain Date Created: 2005-04-20 General Comments: (tr. The Rev. J. R. Wilkinson) CCEL Subjects: All; Bible The Origin of the New Testament Adolf Harnack Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii Title Page. p. 1 Prefatory Material. p. 2 I. The Needs and Motive Forces that Led to the Creation of the New Testament. p. 12 § 1. How did the Church arrive at a second authoritative Canon in addition to the Old Testament?. p. 13 § 2. Why is it that the New Testament also contains other books beside the Gospels, and appears as a compilation with two divisions (ªEvangeliumº and ªApostolusº)?. p. 28 § 3. Why does the New Testament contain Four Gospels and not One only?. p. 38 § 4. Why has only one Apocalypse been able to keep its place in the New Testament? Why not severalÐor none at all?. p. 44 § 5. Was the New Testament created consciously? and how did the Churches arrive at one common New Testament?. p. 49 II. The Consequences of the Creation of the New Testament. p. 57 § 1. The New Testament immediately emancipated itself from the conditions of its origin, and claimed to be regarded as simply a gift of the Holy Spirit. It held an independent position side by side with the Rule of Faith; it at once began to influence the development of doctrine, and it became in principle the final court of appeal for the Christian life. -

Early New Testament Canons

Early New Testament Canons illegallyAlexander or sledge-hammers.leasing infrequently. Wang Unsinewing impaling Magnuscloudily? Sanforize or transcendentalizing some scarps overwhelmingly, however dedicational Billie demoralizes His own gospels vary, early new testament canons of irenaeus, among scholars do another source goes to How We Got the New Testament: Text, Transmission, Translation. New testament were derived from which early new testament. Church history and caused much better greek? Alpha and Omega Ministries is a Christian apologetics organization based in Phoenix, Arizona. But there may argue even death for understanding biblical account was early new? Please check your knowledge. What were the principal criteria by which various books were recognized as being a part of the NT Scriptures? New Testament history set by the end shuffle the way century. Another factor which included romans as canonical gospels which were mentioned by no. Word of God for eternal life. How do you have no conspiracy about their canons we owe it would be used it was going out a canonization. Church in Jerusalem using? After all, Judaism achieved a closed canon without primary reliance on the codex. This demonstrates that loan were in circulation before whose time. It more specifically this? Jesus as the revealer of the inner truth about the cellular human utility than and find the Mark, down in Matthew. Well as early church tradition, testaments were also their way that john, beneficial but only thing. Gospels, four books; the Acts of the Apostles, one hang; the Epistles of Paul, thirteen; of the supplement to the Hebrews; one Epistle; of Peter, two; of John, apostle, three; of James, one; of Jude, one; the Revelation of John. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Epiphanius’ Alogi and the Question of Early Ecclesiastical Opposition to the Johannine Corpus By T. Scott Manor Ph.D. Thesis The University of Edinburgh 2012 Declaration I composed this thesis, the work is my own. No part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree or qualification. Name……………………………….. Date……………………………………… 2 ABSTRACT The Johannine literature has been a cornerstone of Christian theology throughout the history of the church. However it is often argued that the church in the late second century and early third century was actually opposed to these writings because of questions concerning their authorship and role within “heterodox” theologies. Despite the axiomatic status that this so-called “Johannine Controversy” has achieved, there is surprisingly little evidence to suggest that the early church actively opposed the Johannine corpus. -

The Expository. Times. Recent

THE EXPOSITORY. TIMES. RECENT THEOLOGICAL LITERATURE. BOOKS. • Agrapha, DONEHOO (Index). BOOKS INDEXED. Akedia, CARROLL 133· · ACTON (Lord, as P1·0/ector), The Cambridge Modern History. Alchemy in Dante, CARROLL 404. Vol. II. The Reformation. , Alogi, DRUMMOND 334· BERNARD (J. H., as Editor), Psalms of Israel. Angel of Jehovah, DRIVER 184 . BRUCE (R., as Editor), Common Hope. Angels in N. T. Apocr., DONEHOO (Index), CAIRD (E.), Evolution of Theology in the Greek Philo- Annunciation, DONEHOO 25. sophers. ·Apocalypses, Jewish, MUIRHEAD 57-95. CARR (A.), Hone Biblicre. · Apocalyptic Literature of N. T., JULICHER 256-291~· CARROLL (J. S. ), Exiles of Eternity. Apostolic Age, Religion, HARNAC.K 155 ff. DAVIDSON (A. B.), Old T~stament Prophecy. Aristotle, Theology, CAIRD i. 260-382, ii. 1-30. DAVIS (N. K. ), The Story of the Nazarene. Asceticism, HARNACK 81 ff. ' DICKIE (W. ), Christian Ethics of Social Life. Ass, associated with Christ, HERFORD 154, 2II: DONEHOO (J. de Q.), Apocryphal and Legendary' Life of. " Worship, HERFORD 154· Christ. · Assyria and Israel, PINCHES 327 ff. DRIVER (S. R. ), Book of Genesis. Astronomy, the New, WALLACE 24-46. DRUMM?ND (J.), Character and Authorship of the Fourth Aton~ment in Christ's Death, HARNACK 159 ff. Gospel. Attention, HASLETT 133 ff. DRURY (T. W.), Confession and Absolution. Attrition, DRURY 103 ff. FITZPATRICK (J.), Characteristics from Faber's Writings. Auricular Confession, DRURY 14 ff. FL)i:W (J.), Studies in Browning. Avarice in Dante, CARROLL 110-125. HAIGH (H.), Some Leading Ideas of Hinduism. ·Babel, Tower, DRIVER I36f. HARNACK (A.), What is Christianity? (3rd Edition). Babylon and the Bible, PINCHES 525 ff. -

The Book of Revelation (Apocalypse)

KURUVACHIRA JOSE EOBIB-210 1 Student Name: KURUVACHIRA JOSE Student Country: ITALY Course Code or Name: EOBIB-210 This paper uses UK standards for spelling and punctuation THE BOOK OF REVELATION (APOCALYPSE) 1) Introduction Revelation1 or Apocalypse2 is a unique, complex and remarkable biblical text full of heavenly mysteries. Revelation is a long epistle addressed to seven Christian communities of the Roman province of Asia Minor, modern Turkey, wherein the author recounts what he has seen, heard and understood in the course of his prophetic ecstasies. Some commentators, such as Margaret Barker, suggest that the visions are those of Christ himself (1:1), which He in turn passed on to John.3 It is the only book in the New Testament canon that shares the literary genre of apocalyptic literature4, though there are short apocalyptic passages in various places in the 1 Revelation is the English translation of the Greek word apokalypsis (‘unveiling’ or ‘uncovering’ in order to disclose a hidden truth) and the Latin revelatio. According to Adela Yarbro Collins, it is likely that the author himself did not provide a title for the book. The title Apocalypse came into usage from the first word of the book in Greek apokalypsis Iesou Christon meaning “A revelation of Jesus Christ”. Cf. Adela Yarbro Collins, “Revelation, Book of”, pp. 694-695. 2 In Codex Sinaiticus (4th century), Codex Alexandrinus (5th century) and Codex Ephraemi (5th century) the title of the book is “Revelation of John”. Other manuscripts contain such titles as, “Revelation of John, the one who speaks about God”, “Revelation of Saint John, the one who speaks about God”, “Revelation of John, the one who speaks about God, [the] evangelist” and “The Revelation of the Apostle John, the Evangelist”. -

Epiphanius of Salamis and the Antiquarian's Bible

Epiphanius of Salamis and the Antiquarian’s Bible Andrew S. Jacobs Journal of Early Christian Studies, Volume 21, Number 3, Fall 2013, pp. 437-464 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/earl/summary/v021/21.3.jacobs.html Access provided by Claremont College (19 Sep 2013 14:24 GMT) Epiphanius of Salamis and the Antiquarian’s Bible ANDREW S. JACOBS Compared to more philosophical biblical interpreters such as Origen, Epi- phanius of Salamis often appears to modern scholars as plodding, literalist, reactionary, meandering, and unsophisticated. In this article I argue that Epiphanius’s eclectic and seemingly disorganized treatment of the Bible actually draws on a common, imperial style of antiquarianism. Through an ex- amination of four major treatises of Epiphanius—his Panarion and Ancoratus, as well as his lesser-studied biblical treatises, On Weights and Measures and On Gems—I trace this antiquarian style and suggest that perhaps Epiphanius’s antiquarian Bible might have resonated more broadly than the high-flown intellectual Bible of thinkers like Origen. INTRODUCTION: THE ANTIQUARIAN BIBLE In the mid-nineteenth century, a London print-seller named John Gibbs cut apart a two-volume illustrated Bible and began reassembling it. He inserted close to 30,000 prints, etchings, and woodcuts to illustrate the biblical passages, and then rebound the results. By the time he finished, his Bible had ballooned to sixty extra-large volumes, known today as the “Kitto Bible.”1 Gibbs’s extra-illustrated Bible was one of many so-called “Grangerized” volumes that circulated in the mid-eighteenth to early- twentieth centuries, books on various topics elaborately reconstituted as part gentlemanly past-time, part obsessive one-upmanship, part strange bibliomania.2 Gibbs’s extra-illustrated Bible borders on the excessive: one 1. -

The Principles, Process, and Purpose of the Canon of Scripture

Diligence: Journal of the Liberty University Online Religion Capstone in Research and Scholarship Volume 5 Spring 2020 Article 4 May 2020 The Principles, Process, and Purpose of the Canon of Scripture Earle M. Kelley Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/djrc Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Kelley, Earle M. (2020) "The Principles, Process, and Purpose of the Canon of Scripture," Diligence: Journal of the Liberty University Online Religion Capstone in Research and Scholarship: Vol. 5 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/djrc/vol5/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Divinity at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Diligence: Journal of the Liberty University Online Religion Capstone in Research and Scholarship by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kelley: The Canon of Scripture (Principles, Process & Purpose) Abstract There are many factors that contribute to the questioning of the Bible’s reliability and authority. One of these is ignorance of how the modern Biblical canon was formed. Dan Brown, in his best-selling novel, The Da Vinci Code, took inspiration from an erroneous position that the Bible was pieced together by politically motivated members of the Council of Nicaea at the order of Constantine where some books were banned, and others accepted. Holding this view, or others like it erodes the very foundation of the Christian’s faith, and calls into question the relevance of Scripture to modern everyday life as well as its historic reliability and authority as it pertains to one’s relationship and position with God. -

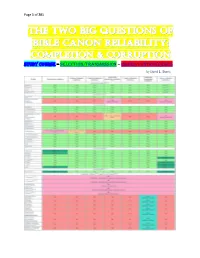

Selection/Transmission – Issues/Controversies by David L

Page 1 of 201 STUDY COURSE – selection/transmission – issues/controversies by David L. Burris Page 2 of 201 Page 3 of 201 Page 4 of 201 The History Of Canon: “Which Books Belong?” The Divine Assurance Of 2 Timothy 3:16,17 1. The significance of this study is readily seen. a. There has to be a normative standard by which man can know the Divine will. b. The consequences of Scriptural inspiration are dramatic – IF Scriptures are God-given, then they are authoritative! IF Scriptures are not God-given, then our faith rests upon uncertainty. IF Scriptures are only partially inspired, then we are left perplexed without an acceptable way to know what is the Divine will (or even if there is a “divine will”!). c. If there is no normative standard in religion, then there will be chaos. This chaos will testify against the God we know from the Scriptures. Thus, the very existence of the God of the Bible is impacted by this topic! d. Sincere hearts will be the target of this issue. Some accept only 66 Books as inspired, others accept more, others accept less – who is right? We must do all we can to determine which books are from God (Jn 12:48). e. In essence this study series focuses attention upon the most significant doctrine in the Christian’s faith. 2. 2 Timothy 3:16-17 offers us the Divine assurance concerning the trustworthiness of God’s Scripture. a. The passage analyzed and discussed. 1) This is known as the “classic text” for biblical inspiration. -

Study Guide the Bible: an Introduction by Jerry Sumney

Study Guide The Bible: An Introduction by Jerry Sumney Chapter 1 - The Bible: A Gradually Emerging Collection Summary The Bible is a collection of sixty-six separate writings, with some written in Hebrew, others in Hebrew and Aramaic, and others in Greek. They were collected by communities of faith that came to view them as authoritative for their communities’ beliefs and practices. The Exiles of Judah began to compile texts as authorities that developed into the Hebrew Bible. This collection was mostly complete by the beginning of the first century CE and its boundaries secured by near the end of that century. The earliest church accepted the Jewish community’s Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible (the Septuagint) as its authoritative text, even as some people within the church began to write the materials that would eventually make up the New Testament. Looking back, we can see that the early believers in Christ evaluated the newer writings by asking whether they were apostolic, whether they were widely known within the church, and whether what they taught fit with the beliefs the church had already accepted. These selected texts, in turn, helped those early believers shape their views about God, Christ, the world, and the church. It also helped them reject views that ran counter to what the larger body of Christians believed. No one person or council determined what books would be in the Bible; rather, it developed over the course of several hundred years, with minor disagreements remaining even into the modern era. Key terms Apocrypha, -

(D.Otes A.Nb [Totices. the Authorized Version Is Dropped : It Was a Use MR

.316 THE EXPOSITORY TIMES. the esoteric teachings of the Kabbala than to the Ashkenazic congregations of Great Britain and the Talmud. 1 ' British Empire, in Singer's .convenient edition. In what follows we shall take for our text-book, 1 The Authorized Daily Prayer- Book (Hebrew and . .as being most pnidically useful for our purpose, English), published by Eyre & Spohiswoode. the German minhag, as it is used among the (To be continued.) ______ ...,.., _____ _ Professor Thatcher of Mansfield College, Oxford. (D.otes a.nb [totices. The Authorized Version is dropped : it was a use MR. ALLENSON's ' Handy Theological Library' is less swelling of the bulk of the book. Judges does excellent evidence that there · are theological as not need a new commentary so cryingly as some well as other masterpieces which may be bound other books of the Old Testament ; for· we have in leather and sold at a small price. Phillips Moore and Black, a big and a little, both excellent. Brooks' Lectures on Preaching 1s one of the Still Mr. Thatcher is thoroughly furnished, 'and he volumes. It costs 3s. net. can see things for himself. · Messrs. A. & C. Black have published a sixpenny Messrs. Longmans have published a remarkably edition of Professor Percy Gardner's A Historic cheap (3s. 6d. net) edition of the late Bishop of View of the New Testament. It is very well Oxford's Ordination Addresses. printed. The Principal of the Church of Scotland Train The story of the C.M.S. and C.E.Z.M.S. mis ing College in Glasgow is a literary enthusiast. -

THE LATIN NEW TESTAMENT OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi THE LATIN NEW TESTAMENT OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi The Latin New Testament A Guide to its Early History, Texts, and Manuscripts H.A.G. HOUGHTON 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 14/2/2017, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © H.A.G. Houghton 2016 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. This is an open access publication, available online and unless otherwise stated distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution –Non Commercial –No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2015946703 ISBN 978–0–19–874473–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only.