Marcion, Papias, and 'The Elders'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adult Sunday School Lesson Nassau Bay Baptist Church December 6, 2020

Adult Sunday School Lesson Nassau Bay Baptist Church December 6, 2020 In this beginning of the Gospel According to Luke, we learn why Luke wrote this account and to whom it was written. Then we learn about the birth of John the Baptist and the experience of his parents, Zacharias and Elizabeth. Read Luke 1:1-4 Luke tells us that many have tried to write a narrative of Jesus’ redemptive life, called a gospel. Attached to these notes is a list of gospels written.1 The dates of these gospels span from ancient to modern, and this list only includes those about which we know or which have survived the millennia. Canon The Canon of Scripture is the list of books that have been received as the text that was inspired by the Holy Spirit and given to the church by God. The New Testament canon was not “closed” officially until about A.D. 400, but the churches already long had focused on books that are now included in our New Testament. Time has proven the value of the Canon. Only four gospels made it into the New Testament Canon, but as Luke tells us, many others were written. Twenty-seven books total were “canonized” and became “canonical” in the New Testament. In the Old Testament, thirty-nine books are included as canonical. Canonical Standards Generally, three standards were held up for inclusion in the Canon. • Apostolicity—Written by an Apostle or very close associate to an Apostle. Luke was a close associate of Paul. • Orthodoxy—Does not contradict previously revealed Scripture, such as the Old Testament. -

Church History Literacy Martyrs

CHURCH HISTORY LITERACY HERESIES – PART ONE The Gnostics #1 Lesson 8 Biblical-Literacy.com © Copyright 2006 by W. Mark Lanier. Permission hereby granted to reprint this document in its entirety without change, with reference given, and not for financial profit. We are told: We are told: • 14 Year old Joseph Smith We are told: • 14 Year old Joseph Smith • “all the religious denominations were believing in false doctrines We are told: We are told: • 17 Year old Joseph Smith We are told: • 17 Year old Joseph Smith • Angel Moroni appears We are told: • 17 Year old Joseph Smith • Angel Moroni appears We are told: We are told: We are told: • September 1827 gets gold plates We are told: • September 1827 gets gold plates We are told: We are told: • “Reformed Egyptian” We are told: • “Reformed Egyptian” •The “Secrets” are revealed! Solomon said: Solomon said: There is nothing new under the sun. Is there anything of which one can say, ‘Look! This is something new?’ (Ec. 1:9) Mormonism Teaches “Heresy” Mormonism Teaches “Heresy” Heresy: Teaching claiming to be Christian that is contrary to Orthodoxy Mormonism Teaches “Heresy” Heresy: Teaching claiming to be Christian that is contrary to Orthodoxy Mormonism Teaches “Heresy” Heresy: Teaching claiming to be Christian that is contrary to Orthodoxy Lessons Today • Truth Matters Lessons Today • Road to heresy not always a U- turn Lessons Today • Core understanding vs. complete understanding Lessons Today • Be wary of goofy interpretations Major Heresy: Gnosticism Major Heresy: Gnosticism Major Heresy: -

The Origin of the New Testament by Adolf Harnack About the Origin of the New Testament by Adolf Harnack

The Origin of the New Testament by Adolf Harnack About The Origin of the New Testament by Adolf Harnack Title: The Origin of the New Testament URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/harnack/origin_nt.html Author(s): Harnack, Adolf (1851-1930) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Rights: Public Domain Date Created: 2005-04-20 General Comments: (tr. The Rev. J. R. Wilkinson) CCEL Subjects: All; Bible The Origin of the New Testament Adolf Harnack Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii Title Page. p. 1 Prefatory Material. p. 2 I. The Needs and Motive Forces that Led to the Creation of the New Testament. p. 12 § 1. How did the Church arrive at a second authoritative Canon in addition to the Old Testament?. p. 13 § 2. Why is it that the New Testament also contains other books beside the Gospels, and appears as a compilation with two divisions (ªEvangeliumº and ªApostolusº)?. p. 28 § 3. Why does the New Testament contain Four Gospels and not One only?. p. 38 § 4. Why has only one Apocalypse been able to keep its place in the New Testament? Why not severalÐor none at all?. p. 44 § 5. Was the New Testament created consciously? and how did the Churches arrive at one common New Testament?. p. 49 II. The Consequences of the Creation of the New Testament. p. 57 § 1. The New Testament immediately emancipated itself from the conditions of its origin, and claimed to be regarded as simply a gift of the Holy Spirit. It held an independent position side by side with the Rule of Faith; it at once began to influence the development of doctrine, and it became in principle the final court of appeal for the Christian life. -

The Apocryphal Gospels

A NOW YOU KNOW MEDIA W R I T T E N GUID E The Apocryphal Gospels: Exploring the Lost Books of the Bible by Fr. Bertrand Buby, S.M., S.T.D. LEARN WHILE LISTENING ANYTIME. ANYWHERE. THE APOCRYPHAL GOSPELS: EXPLORING THE LOST BOOKS OF THE BIBLE WRITTEN G U I D E Now You Know Media Copyright Notice: This document is protected by copyright law. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. You are permitted to view, copy, print and distribute this document (up to seven copies), subject to your agreement that: Your use of the information is for informational, personal and noncommercial purposes only. You will not modify the documents or graphics. You will not copy or distribute graphics separate from their accompanying text and you will not quote materials out of their context. You agree that Now You Know Media may revoke this permission at any time and you shall immediately stop your activities related to this permission upon notice from Now You Know Media. WWW.NOWYOUKNOWMEDIA.COM / 1 - 800- 955- 3904 / © 2010 2 THE APOCRYPHAL GOSPELS: EXPLORING THE LOST BOOKS OF THE BIBLE WRITTEN G U I D E Table of Contents Topic 1: An Introduction to the Apocryphal Gospels ...................................................7 Topic 2: The Protogospel of James (Protoevangelium of Jacobi)...............................10 Topic 3: The Sayings Gospel of Didymus Judas Thomas...........................................13 Topic 4: Apocryphal Infancy Gospels of Pseudo-Thomas and Others .......................16 Topic 5: Jewish Christian Apocryphal Gospels ..........................................................19 -

When Did the Old Testament Become Insufficient?

When did the Old Testament become insufficient? Yes, of course, we do need the New Testament, but why? Why is the Old Testament not enough? By asking that question, I am reversing the one Christians ask under their breath, the question whether we need the Old Testament, or whether the New Testament isn’t enough. Two bishops once met in a bar (I expect it wasn’t actually a bar, but it makes for a better story). The bishops were called Polycarp and Marcion. When Marcion asked Polycarp if he knew who he was, Polycarp replied, “I know you, the firstborn of Satan!” We know about Do We Need the New their meeting from the writings of another bishop, Irenaeus; all three lived in the second Testament?: Letting the Old century A.D. and were originally from Turkey. Marcion had come to some beliefs that were Testament Speak for Itself rather different from those of “orthodox” bishops such as Irenaeus and Polycarp. Among Available June 2015 other things, he believed that the teachings of Jesus clashed irreconcilably with the picture of $22, 184 pages, paperback God conveyed by the Jewish Scriptures—what we call “the Old Testament,” but that title 978-0-8308-2469-4 hadn’t yet come into use (neither was there yet a “New Testament”). While Polycarp likely had in mind Marcion’s more general beliefs, someone like me who is passionate about the Old Testament may be forgiven for a high five in response to this greeting. Indeed, I am “Reflecting on new perspectives tempted to sympathize with the views of Cerinthus, another Turkish theologian about whom Polycarp himself passes on a story. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Epiphanius’ Alogi and the Question of Early Ecclesiastical Opposition to the Johannine Corpus By T. Scott Manor Ph.D. Thesis The University of Edinburgh 2012 Declaration I composed this thesis, the work is my own. No part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree or qualification. Name……………………………….. Date……………………………………… 2 ABSTRACT The Johannine literature has been a cornerstone of Christian theology throughout the history of the church. However it is often argued that the church in the late second century and early third century was actually opposed to these writings because of questions concerning their authorship and role within “heterodox” theologies. Despite the axiomatic status that this so-called “Johannine Controversy” has achieved, there is surprisingly little evidence to suggest that the early church actively opposed the Johannine corpus. -

Download Ancient Apocryphal Gospels

MARKus BOcKMuEhL Ancient Apocryphal Gospels Interpretation Resources for the Use of Scripture in the Church BrockMuehl_Pages.indd 3 11/11/16 9:39 AM © 2017 Markus Bockmuehl First edition Published by Westminster John Knox Press Louisville, Kentucky 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26—10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the pub- lisher. For information, address Westminster John Knox Press, 100 Witherspoon Street, Louisville, Kentucky 40202- 1396. Or contact us online at www.wjkbooks.com. Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. and are used by permission. Map of Oxyrhynchus is printed with permission by Biblical Archaeology Review. Book design by Drew Stevens Cover design by designpointinc.com Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Bockmuehl, Markus N. A., author. Title: Ancient apocryphal gospels / Markus Bockmuehl. Description: Louisville, KY : Westminster John Knox Press, 2017. | Series: Interpretation: resources for the use of scripture in the church | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016032962 (print) | LCCN 2016044809 (ebook) | ISBN 9780664235895 (hbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781611646801 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Apocryphal Gospels—Criticism, interpretation, etc. | Apocryphal books (New Testament)—Criticism, interpretation, etc. Classification: LCC BS2851 .B63 2017 (print) | LCC BS2851 (ebook) | DDC 229/.8—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016032962 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48- 1992. -

The Expository. Times. Recent

THE EXPOSITORY. TIMES. RECENT THEOLOGICAL LITERATURE. BOOKS. • Agrapha, DONEHOO (Index). BOOKS INDEXED. Akedia, CARROLL 133· · ACTON (Lord, as P1·0/ector), The Cambridge Modern History. Alchemy in Dante, CARROLL 404. Vol. II. The Reformation. , Alogi, DRUMMOND 334· BERNARD (J. H., as Editor), Psalms of Israel. Angel of Jehovah, DRIVER 184 . BRUCE (R., as Editor), Common Hope. Angels in N. T. Apocr., DONEHOO (Index), CAIRD (E.), Evolution of Theology in the Greek Philo- Annunciation, DONEHOO 25. sophers. ·Apocalypses, Jewish, MUIRHEAD 57-95. CARR (A.), Hone Biblicre. · Apocalyptic Literature of N. T., JULICHER 256-291~· CARROLL (J. S. ), Exiles of Eternity. Apostolic Age, Religion, HARNAC.K 155 ff. DAVIDSON (A. B.), Old T~stament Prophecy. Aristotle, Theology, CAIRD i. 260-382, ii. 1-30. DAVIS (N. K. ), The Story of the Nazarene. Asceticism, HARNACK 81 ff. ' DICKIE (W. ), Christian Ethics of Social Life. Ass, associated with Christ, HERFORD 154, 2II: DONEHOO (J. de Q.), Apocryphal and Legendary' Life of. " Worship, HERFORD 154· Christ. · Assyria and Israel, PINCHES 327 ff. DRIVER (S. R. ), Book of Genesis. Astronomy, the New, WALLACE 24-46. DRUMM?ND (J.), Character and Authorship of the Fourth Aton~ment in Christ's Death, HARNACK 159 ff. Gospel. Attention, HASLETT 133 ff. DRURY (T. W.), Confession and Absolution. Attrition, DRURY 103 ff. FITZPATRICK (J.), Characteristics from Faber's Writings. Auricular Confession, DRURY 14 ff. FL)i:W (J.), Studies in Browning. Avarice in Dante, CARROLL 110-125. HAIGH (H.), Some Leading Ideas of Hinduism. ·Babel, Tower, DRIVER I36f. HARNACK (A.), What is Christianity? (3rd Edition). Babylon and the Bible, PINCHES 525 ff. -

The Book of Revelation (Apocalypse)

KURUVACHIRA JOSE EOBIB-210 1 Student Name: KURUVACHIRA JOSE Student Country: ITALY Course Code or Name: EOBIB-210 This paper uses UK standards for spelling and punctuation THE BOOK OF REVELATION (APOCALYPSE) 1) Introduction Revelation1 or Apocalypse2 is a unique, complex and remarkable biblical text full of heavenly mysteries. Revelation is a long epistle addressed to seven Christian communities of the Roman province of Asia Minor, modern Turkey, wherein the author recounts what he has seen, heard and understood in the course of his prophetic ecstasies. Some commentators, such as Margaret Barker, suggest that the visions are those of Christ himself (1:1), which He in turn passed on to John.3 It is the only book in the New Testament canon that shares the literary genre of apocalyptic literature4, though there are short apocalyptic passages in various places in the 1 Revelation is the English translation of the Greek word apokalypsis (‘unveiling’ or ‘uncovering’ in order to disclose a hidden truth) and the Latin revelatio. According to Adela Yarbro Collins, it is likely that the author himself did not provide a title for the book. The title Apocalypse came into usage from the first word of the book in Greek apokalypsis Iesou Christon meaning “A revelation of Jesus Christ”. Cf. Adela Yarbro Collins, “Revelation, Book of”, pp. 694-695. 2 In Codex Sinaiticus (4th century), Codex Alexandrinus (5th century) and Codex Ephraemi (5th century) the title of the book is “Revelation of John”. Other manuscripts contain such titles as, “Revelation of John, the one who speaks about God”, “Revelation of Saint John, the one who speaks about God”, “Revelation of John, the one who speaks about God, [the] evangelist” and “The Revelation of the Apostle John, the Evangelist”. -

Ebionites. Cerinthus ( Fl. C.100)

Ebionites. An ascetic sect of Jewish Christians which flourished on the E. of the R. Jordan in the early years of the Christian era. Their main tenets seem to have been: 1. 1 a ‘reduced’ doctrine of the Person of Christ, to the effect, e.g., that Jesus was the human son of Joseph and Mary and that the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove alighted on Him at His Baptism, and 2. 2 overemphasis on the binding character of the Mosaic Law. They are said to have rejected the Pauline Epistles and to have used only one Gospel. Cerinthus ( fl. c.100), Gnostic. He is said to have taught that the world was created, not by the supreme God, but either by a Demiurge (a less exalted being) or by angels. Jesus, he held, began His earthly life as a mere man, though at His Baptism ‘the Christ’, a higher Divine power, descended upon Him, but departed before the crucifixion. Jerome, St (c.345–420), biblical scholar. He was born near Aquileia. About 374 he set off for Palestine. He spent some time in Antioch and then lived for four or five years as a hermit in the Syrian desert; here he learnt Hebrew. From 382 to 385 he was in Rome, where he acted as secretary to Pope Damasus and successfully preached asceticism (see Melania; paula). In 386 he settled in Bethlehem, where he ruled over a newly-founded monastery. Jerome's scholarship was unsurpassed in the early Church. His greatest achievement was his translation of most of the Bible into Latin from the original languages (see Vulgate). -

Epiphanius of Salamis and the Antiquarian's Bible

Epiphanius of Salamis and the Antiquarian’s Bible Andrew S. Jacobs Journal of Early Christian Studies, Volume 21, Number 3, Fall 2013, pp. 437-464 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/earl/summary/v021/21.3.jacobs.html Access provided by Claremont College (19 Sep 2013 14:24 GMT) Epiphanius of Salamis and the Antiquarian’s Bible ANDREW S. JACOBS Compared to more philosophical biblical interpreters such as Origen, Epi- phanius of Salamis often appears to modern scholars as plodding, literalist, reactionary, meandering, and unsophisticated. In this article I argue that Epiphanius’s eclectic and seemingly disorganized treatment of the Bible actually draws on a common, imperial style of antiquarianism. Through an ex- amination of four major treatises of Epiphanius—his Panarion and Ancoratus, as well as his lesser-studied biblical treatises, On Weights and Measures and On Gems—I trace this antiquarian style and suggest that perhaps Epiphanius’s antiquarian Bible might have resonated more broadly than the high-flown intellectual Bible of thinkers like Origen. INTRODUCTION: THE ANTIQUARIAN BIBLE In the mid-nineteenth century, a London print-seller named John Gibbs cut apart a two-volume illustrated Bible and began reassembling it. He inserted close to 30,000 prints, etchings, and woodcuts to illustrate the biblical passages, and then rebound the results. By the time he finished, his Bible had ballooned to sixty extra-large volumes, known today as the “Kitto Bible.”1 Gibbs’s extra-illustrated Bible was one of many so-called “Grangerized” volumes that circulated in the mid-eighteenth to early- twentieth centuries, books on various topics elaborately reconstituted as part gentlemanly past-time, part obsessive one-upmanship, part strange bibliomania.2 Gibbs’s extra-illustrated Bible borders on the excessive: one 1. -

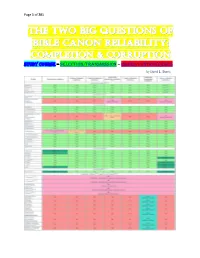

Selection/Transmission – Issues/Controversies by David L

Page 1 of 201 STUDY COURSE – selection/transmission – issues/controversies by David L. Burris Page 2 of 201 Page 3 of 201 Page 4 of 201 The History Of Canon: “Which Books Belong?” The Divine Assurance Of 2 Timothy 3:16,17 1. The significance of this study is readily seen. a. There has to be a normative standard by which man can know the Divine will. b. The consequences of Scriptural inspiration are dramatic – IF Scriptures are God-given, then they are authoritative! IF Scriptures are not God-given, then our faith rests upon uncertainty. IF Scriptures are only partially inspired, then we are left perplexed without an acceptable way to know what is the Divine will (or even if there is a “divine will”!). c. If there is no normative standard in religion, then there will be chaos. This chaos will testify against the God we know from the Scriptures. Thus, the very existence of the God of the Bible is impacted by this topic! d. Sincere hearts will be the target of this issue. Some accept only 66 Books as inspired, others accept more, others accept less – who is right? We must do all we can to determine which books are from God (Jn 12:48). e. In essence this study series focuses attention upon the most significant doctrine in the Christian’s faith. 2. 2 Timothy 3:16-17 offers us the Divine assurance concerning the trustworthiness of God’s Scripture. a. The passage analyzed and discussed. 1) This is known as the “classic text” for biblical inspiration.