Hello and Welcome Back to the Third Episode of Good Ancestor Podcast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards Hope

A SEA OF WORDS 4TH YEAR Towards Hope Alaa Almalfouth. Palestine The wide-brimmed hat he was wearing could The news was more painful than a dagger not stop him sweating from his forehead and stabbing his chest. He walked towards the offi- cheeks, just as his sunglasses could not con- cer through the crowd of travellers, who raised ceal his obvious watchful gaze. He was hold- their angry furious voices, and tried to question ing luggage laden with clothes and personal the closure. The officer interrupted, telling him things, as his heart was loaded with endless that the Palestinian side is powerless. troubles and immense pain. The long wait Samy dragged his feet as depression since the early morning made him lose all his and grief added twenty years to his twenty- energy, despite the fatty breakfast he had eat- five year old face. He took a bus home, leav- en, which was prepared for him by his mother ing the crossing and abandoning his dreams. while she bid him a farewell and murmured: It did not take long for him to reach home; he “Samy, this is the last breakfast for you rushed to his bed and drifted into deep sleep. in Gaza and, God willing, your breakfast to- The sunrays infiltrating the window morrow will be in Manchester.” burned his face, and an intruding fly buzzed He smiled as he recalled this situation. around him. He tried to continue sleeping The growing fatigue made him unashamed but the heat of the sun and the buzzing fly to sit on his suitcase, and he started to scan prevented him. -

Pressed on 180 Gram HQ, This Specially Packaged Release Includes New Artwork and a Full CD of the Album

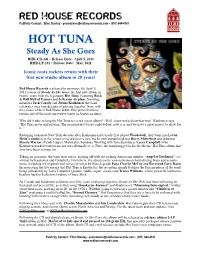

RED HOUSE RECORDS Publicity Contact: Ellen Stanley • [email protected] • (651) 644-4161 HOT TUNA Steady As She Goes RHR-CD-241 • Release Date: April 5, 2011 RHR-LP-241 • Release Date: May, 2011 Iconic roots rockers return with their first new studio album in 20 years! Red House Records is pleased to announce the April 5, 2011 release of Steady As She Goes, the first new album in twenty years from the legendary Hot Tuna. Featuring Rock & Roll Hall of Famers and Jefferson Airplane founding members Jack Casady and Jorma Kaukonen, the band celebrates over four decades of playing together. Now, with the release of their Red House debut, they prove that they remain one of the most innovative bands in American music. Why did it take so long for Hot Tuna to record a new album? “Well, it just worked out that way,” Kaukonen says. “Hot Tuna never quit playing. The moment just wasn’t right before; now it is, and we have a great project to show for it.” Returning to upstate New York decades after Kaukonen and Casady first played Woodstock, they went into Levon Helm’s studio over the winter to record twelve new tracks with mandolin player Barry Mitterhoff and drummer Skoota Warner (Cyndi Lauper, Matisyahu, Santana). Working with famed producer Larry Campbell (who Kaukonen worked with on his last solo album River of Time) the band plugged in for the electric Hot Tuna album that fans have been waiting for. Taking no prisoners, the band tears into it, kicking off with the rocking Americana number “Angel of Darkness” (co- written by Kaukonen and Campbell). -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

VIBE ACTIVITIES Issueyears 198 K-1

Years K-1 Y E A R Name: K-1 VIBE ACTIVITIES IssueYears 198 K-1 Female Artist of the Year – Jessica Mauboy page 7 Shellie Morris DeGeneres Show. In April, she was ranked at number 16 on FEMALE ARTIST Contemporary folk musician Shellie Morris the Herald-Sun’s list of the ‘100 was raised in Sydney and began singing at a Greatest Australian Singers of All Time’. young age. As a young woman she moved Mauboy has been in the US working OF THE YEAR to Darwin to find her Indigenous family and on her upcoming third studio album, also found her musical legacy. That connection which is due for release in late 2013. and knowledge has helped her become a talented and popular singer/songwriter with musicals, Hollywood blockbusters and a voice that has been described as “soaring”. Casey Donovan collaborations with showbiz and musical At the age of 16, Casey Donovan became luminaries, such as Baz Luhrmann, Paul Kelly Shellie has played with artists such as Sinead and David Atkins. O’Connor, Gurrumul and Ricki-Lee Jones and the youngest ever winner of Australian featured as a singer with the Black Arm Band. Idol, and has since made her mark on Anu began her performing career as both the Australian music and theatre a dancer, but quickly moved on to singing Ngambala Wiji Li-Wunungu (Together We are scene. After releasing her debut EP, Eye back-up vocals for The Rainmakers and Strong) is Shellie’s latest release; recorded 2 Eye, Casey was encouraged to try her eventually releasing her own solo material, with family members from her grandmother’s hand at theatre where she received which has produced platinum- and country in Borroloola, the album is sung critical acclaim for her roles in the 2010 gold-selling albums and singles, including entirely in several Indigenous languages. -

2012 Publication

Editor’s Note Dear Artists and Authors, Works of literature, whether whimsical or profound, arise from inspiration, consideration, observation and craft. At times the words flow effortlessly from the pen; occasionally the grip becomes worn and the ink nearly dries before producing works of merit. We call this creative writing. It is a highly coveted skill that makes this journal possible. Clearly, as one can see from perusing page-to-page, the end justifies the means. However, it has occurred to me in a powerful epiphany as I began reading and editing that the true art does not come to completion with publication or press release. No, the true art comes to fruition perennially via you, the reader. We call the process creative writing but the purpose is realized through a creative understanding, a creative interpretation formed from experience and phenomenology. In many ways, much like a piece of paper is a canvas for the writer, the literature itself is a canvas for the readers, on which they plant their own perception and unearth a work of art no other reader can harvest. On each page, a multiplicity of stories thrive, far more than the pages of this journal are capable of containing. Your distinct reading will find something different, an exclusive reflection of yourself both fertilized by and budding from the words in a circular and mutual appreciation. This is the very essence of creative understanding. Now turn the page and begin— reap what you will, experience each story in every way you know how and sow a parcel of yourself in our journal. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Waiting Time and Elective Surgery Policy

Policy Directive Waiting Time and Elective Surgery Policy Summary The Waiting Time and Elective Surgery Policy is the reference guide for facilities to manage elective surgery and medical waiting lists. The policy covers the procedures that facilities are required to follow to adequately manage waiting lists to ensure that patients are treated within their clinical priority timeframe. Document type Policy Directive Document number PD2012_011 Publication date 01 February 2012 Author branch System Relationships and Frameworks Branch contact 9391 9324 Review date 20 October 2021 Policy manual Patient Matters File number 11/5771 Previous reference N/A Status Review Functional group Clinical/Patient Services - Medical Treatment, Information and Data, Surgical Applies to Local Health Districts, Specialty Network Governed Statutory Health Corporations, Affiliated Health Organisations, Dental Schools and Clinics, Public Hospitals Distributed to Public Health System, Divisions of General Practice, NSW Ambulance Service, Ministry of Health Audience Local Health Districts & Network Executives;Hospital General Managers;Admission/Booking Staff Secretary, NSW Health This Policy Directive may be varied, withdrawn or replaced at any time. Compliance with this directive is mandatory for NSW Health and is a condition of subsidy for public health organisations. POLICY STATEMENT WAITING TIME AND ELECTIVE SURGERY POLICY PURPOSE The Waiting Time and Elective Surgery Policy is the reference guide for facilities to manage elective surgical waiting lists. The policy covers the procedures that facilities are required to follow and adequately manage waiting lists. MANDATORY REQUIREMENTS This policy has been developed to promote clinically appropriate, consistent and equitable management of elective surgery patients and waiting lists in public hospitals across NSW. -

Brian Mcknight Evolution of a Man Album Download Better

brian mcknight evolution of a man album download Better. After the release of More Than Words, Brian McKnight established his own label, Brian McKnight Music, through the artist-friendly Kobalt Label Services, and went about making his third proper studio album outside the major-label system. Even more organic than what immediately preceded it, Better is filled with lively songs that are well crafted but don't seem the least bit fussed over. McKnight sounds like he's having as much fun as ever, gleefully flitting from falsetto disco-funk jams to lonesome, modern country-flavored ballads. It's all free and easy and allows for some whimsical moves, like the reggae backing on "Goodbye" and the tricky prog/pop-funk hybrid "Key 2 My Heart," the latter cut being where his love for Swedish trio Dirty Loops is most evident. There are occasional odd quirks, like the winking manner in which he slips "bitch" into the chorus of "Strut," and the way he throws a sharp curve, the tipsy newfound-love rocker "Just Enough," so early in the sequence. Several tracks do keep it simple and heartfelt, the qualities for which McKnight is most known, heard best on the humble title track, "Uh Oh Feeling," and "Like I Do." Mercifully, this material is a lot less erratic than the back cover typography (which displays McKnight's name as "B. McKnight," "B. Mcknight," "brian mcknight," "Brian McKnight," and "BRIAN MCKNIGHT"). Brian mcknight evolution of a man album download. It won't be long now until Brian McKnight unleashes his new album Evolution Of A Man (October 27th). -

You Are the One You’Ve Been Waiting For

You Are the One You’ve Been Waiting For bringing courageous love to intimate relationships Richard C. Schwartz Lovingly dedicated to my parents Gen and Ted Schwartz my biggest mentors and tor-mentors Copyright © 2008 by Richard C. Schwartz Trailheads Publications™ Publishing Division of The Center for Self Leadership, P.C. Without prejudice, all rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the author. Published by Trailheads Publications, The Center for Self Leadership, P.C., Post Office Box 3969, Oak P ark, Illinois 60303. ISBN: 978-0-615-24932-2 Acknowledgments The words in this book are well earned. I have had relationships with many people that could be considered intimate, and I have learned from all of them. Some of my best teachers have been the clients who have allowed me to experiment with their internal and external families and who have challenged my parts. I’m grateful to them all. Nancy Schwartz is the non-client who taught me the most about intimate partnerships, and suffered the most while I was learning. I’m also extremely grateful to the many other people who have helped me grow personally in this area and who have been patient with my delicate exiles and tiresome protectors. In terms of the production of this book, I am very grateful to Kira Freed for her wonderful and painstaking copyediting and for her generosity with her time. -

DUDE, YOU HEAR WHAT I HEAR? a Christmas Musical for Kids Created by Steve Moore • Rob Howard • David Guthrie

READ THIS SCRIPT ONLINE, BUT PLEASE DON’T PRINT OR COPY IT! DUDE, YOU HEAR WHAT I HEAR? A Christmas Musical for Kids Created by Steve Moore • Rob Howard • David Guthrie (As music begins, lights up on the interior store set, a large superstore named Mondo-Mart. Our Campers are playing “hide-and-seek” in the middle of the crowded store. Our mannequin characters are scattered around the set. Mr. Ebenezer and Mrs. Jones are doing their regular work. Christmas shoppers are frantically working on completing their Christmas lists.) SONG: “DUDE, YOU HEAR WHAT I HEAR?” DUDE, YOU HEAR WHAT I HEAR? Words and Music by Rob Howard chorus Dude, you hear what I hear? Christmas is near This is my favorite season Dude, you hear what I hear? It’s the best time of year And there is a really good reason Hear the story loud and clear It’s everywhere Dude, you hear what I hear? verse 1 Hark the herald angels sing Oh, oh, oh, oh Glory to the newborn King Oh, oh, oh, oh Peace on earth and mercy mild Oh, oh, oh, oh God and sinners reconciled Oh, oh, oh, oh The good news is ringing out If you can hear it let me hear you shout chorus Dude, you hear what I hear? Christmas is near This is my favorite season Dude, you hear what I hear? It’s the best time of year And there is a really good reason Hear the story loud and clear It’s everywhere READ THIS SCRIPT ONLINE, BUT PLEASE DON’T PRINT OR COPY IT! 2 READ THIS SCRIPT ONLINE , BUT PLEASE DON’T PRINT OR COPY IT! Dude, you hear what I hear? verse 2 Joyful all ye nations rise Oh, oh, oh, oh Join the triumph of the skies -

A Guide to Your Stay at Sydney and Sydney Eye Hospital 2021 Please Leave This for the Next Patient (Do Not Remove)

A guide to your stay at Sydney and Sydney Eye Hospital 2021 Please leave this for the next patient (do not remove) For your own copy of this guide, please scan the code with your smartphone camera and a digital download will begin. Scan Me Need an interpreter? Ask the staff ?আপনার কি এিজন দ াভাষীর প্রয় াজন اذا كنت بحاجة الى مترجم আমায় র িমচম ারীয় র কজজ্ঞাসা ি쇁ন اسال موظفي المستشفى Arabic Bengali 需要翻譯員嗎? Treba li Vam tumač? Zamolite osoblje 要的話, 請向職員查詢 Croatian Chinese Χρειάζεστε διερμηνέα; Butuh seorang juru bahasa? Ρωτήστε το προσωπικό Tanyakanlah pada pegawai Greek Indonesian Hai bisogno di un interprete? 通訳が必要ですか? Chiedilo al personale スタッフに申し出て下さい Italian Japanese 통역을 원하십니까? Potrzebujesz tłumacza? 직원에게 문의 하세요 Zwróć się do naszych pracowników Polish Korean Precisa de intérprete? Нужен вам переводчик? Pergunte aos funcionários Обратитесь к нашим сотрудникам Portuguese Russian Да ли вам треба тумач? ¿Necesita un intérprete? Питајте особље Pregúntele al personal Serbian Spanish . Tercümana ıntıyacınız mı var? Personele söyleyın Turkish Thai Quý vị cần thông ngôn viên? Xin hỏi nhân viên Vietnamese FREE 24 hours 7 days DHPOWH2013 2 Contents Welcome 4 Paperwork 16 A message from the General X-rays and scans 16 Manager 4 While you are in hospital 16 Acknowledgement of Country 6 Are you worried about your About Sydney and Sydney Eye loved one in hospital? 18 Hospital 6 Services available on the ward 20 Finding your way at Sydney and In the event of a fire or an Sydney Eye Hospital 7 emergency 20 Privacy and confidentiality 7 Facilities