Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WESTMOUNT HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION the Improvement of the St

NEW ACQUISITIONS The WestmountNEWSLETTEROFTHE WESTMOUNT HISTORICAL HistorianASSOCIATION VOLUME 8 NUMBER 2 FEBRUARY 2008 GUIDO NINCHERI: A FLORENTINE ARTIST IN NORTH ᮣ AMERICA. Montreal: Hochelaga-Maisonneuve Historical Society, 2001. (Catalogue of the exhibition presented at the Chateau Dufresne) WHA looks at some Prominent Westmounters ᮤ LOST MONTREAL, by Luc d’Iberville-Moreau. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1975. THE MIND OF NORMAN BETHUNE, by Roderick Stewart. ᮣ Don Mills, ON: Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 1977. ᮤ REFLECTIONS AND RECOLLECTIONS: ESSAYS, SHORT STORIES, SHORT NOVEL, PLAY, POEMS, WITH AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL NOTES & ARTICLES ON MANY COUNTRIES, by Gerald Glass. Montreal: Self-published, 1996. Donated by the author. TITANIC: THE CANADIAN STORY, by Alan Hustak. ᮣ Montreal: Véhicule Press, 1998. Alice Lighthall (1891-1991) George Hogg (1865-1948) Hon. John Young (1811-1878) One of the founders of WHA in 1944 Founder of Guaranteed Pure Milk Co. Chairman of Montreal Harbour Commission Order of Canada (1973) for work Mayor of Westmount from 1927 to 1932 Owner of Rosemount Estate in Westmount ᮤ ESSAYS ON VARIOUS SUBJECTS: A SHORT STORY: with Indian and Inuit Art A SHORT PLAY: SHORT POEMS (WITH TRANSLATIONS) AND PART II OF THE HISTORY OF THE ACADEMIC AND GENERAL BOOK SHOP (1963) MONTREAL, WITH AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL NOTES, by Gerald Glass. Montreal: Self-published, 1991. (Donated by the author) DONATIONS ᮤ , film by Megan Durnford. Iridescent Film, RT “Just a Lawn” 13 mins 11 sec. Donated by Megan Durnford. “Vieux Temps Stories – Lac-Tremblant-Nord -

Titanic! Photocopiable

LEVEL 3 Activity worksheets Teacher Support Programme Titanic! Photocopiable Chapter 1 f The officers had to …………… people away 1 Put the underlined letters in the right place to from the lifeboats. make a word. 4 Put a word on the left with a word on the a The Titanic was famous because it was the right. world’s bksniuanel ……………… ship. ahead lower b The first, second and third class passengers float quiet slept on tefdirnfe ……………… decks. higher small c The second class passengers had a bliryar large sink ……………… and some bars. loud behind In the 1900s the tallest gdlbiniu d Chapter 3 ……………… in the world was only 5 Answer these questions. 229 meters tall. a Why didn’t many of the third class passengers e Many nszieamga ……………… and understand the danger? newspapers wrote stories about the movie ……………………………………………… Titanic. b How did Officer Lightoller stop some people Titanic f The almost had an caedinct getting into a lifeboat? ……………… at the start of its journey. ……………………………………………… 2 Write the names to finish the sentences. c How long did Harold Bride stay under a James Cameron Mrs. Blanche Marshall lifeboat? Kate Winslet Leonardo DiCaprio ……………………………………………… E.J. Smith Jack Dawson d When the back part of the ship fell back into a ……………………… didn’t want small parts the water, what did the passengers there in Hollywood movies. think? b ……………………… was Rose’s lover in the ……………………………………………… movie Titanic. e How many musicians were in the band? c ……………………… had to go down in a ……………………………………………… submarine. f What did the musicians do just before the d ……………………… was the name of the Titanic sank? Titanic captain of the . -

Westenderwestender

NEWSLETTER of the WEST END LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY WESTENDERWESTENDER MARCH - APRIL 2013 ( PUBLISHED SINCE 1999 ) VOLUME 8 NUMBER 10 THEN AND NOW CHAIRMAN Neville Dickinson VICE-CHAIRMAN Bill White SECRETARY Lin Dowdell MINUTES SECRETARY Vera Dickinson TREASURER Peter Wallace MUSEUM CURATOR Nigel Wood PUBLICITY Ray Upson MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Delphine Kinley RESEARCHER WEST END HIGH STREET LOOKING TOWARDS SHOTTERS HILL c. 1910 Pauline Berry Our feature photograph this edition shows West End High Street around WELHS... preserving our past 1910. The road is compacted dirt, as for your future…. was usual before roads were VISIT OUR tarmacadamed. Shotters Hill is quite clearly seen and the old National WEBSITE! School, latterly the Parish Hall on the left. Our current picture shows the same scene today, albeit with somewhat less Website: traffic than is usual. Gone is the school www.westendlhs.hampshire.org.uk and most of the buildings in the original photograph. THE SAME SCENE TODAY E-mail address: [email protected] West End Local History Society is sponsored by West End Local History Society & Westender is sponsored by EDITOR Nigel.G.Wood EDITORIAL AND PRODUCTION ADDRESS WEST END 40 Hatch Mead West End PARISH Southampton, Hants SO30 3NE COUNCIL Telephone: 023 8047 1886 E-mail: [email protected] WESTENDER - PAGE 2 - VOL 8 NO 10 SARAH SIDDONS … actress A Review by Stan Waight SARAH SIDDONS BY GAINSBOROUGH 1785 THE THEATRE IN FRENCH STREET, SOUTHAMPTON The speaker at our February meeting was our old friend Geoff Watts. I must admit that, before the meeting, I wondered what the link between the famous actress and Southampton might be. -

Men's Fashion in 1912 24

Life in 1912 by ALookThruTime Table of Content Enjoying Life and the Arts in 1912 4 Transportation in 1912 6 Answering the Call of Nature in 1912 9 What did they use for Toilet Paper in 1912 11 Facts about life in 1912 and 2012 13 Schools in 1912 14 Roads in 1912 15 Life Events in 1912 17 Communication in 1912 19 Prices in 1912 21 Women's Fashion in 1912 24 Men's Fashion in 1912 26 Hats and Hairstyles in 1912 28 Life Events in 1912 30 Jobs and Careers in 1912 32 Sports in 1912 34 Women's Roles in 1912 36 Medical and Health Issues in 1912 38 Companies Established In 1912 41 1912 at a Glance 43 Miscellaneous Facts about 1912 44 Headlines of 1912 46 Celebrities in 1912 49 Popular Music of 1912 53 1912--The Year of the Presidents 56 1912 At A Glance 59 Titanic Special: Titanic Is Born 62 Titanic Is Launched 64 Titanic Leaves On Her Maiden Voyage 67 Music on the Titanic 69 First Class Life on the Titanic 72 Second Class Life on the Titanic 78 Third Class Life on the Titanic 81 Alexander's Ragtime Band 85 The Officers and Crew of the Titanic 86 Heroes: The Titanic Band 91 Songs Heard on the Titanic 94 Iceberg, Right Ahead! 96 Autumn, heard the night of Titanic's Sinking 102 Nearer, My God, To Thee, Last Song Played As the Titanic Sinks 104 Carpathia Arrives….Titanic Survivors Are Rescued 106 Carpathia Arrives in New York 110 The Recovery Effort 112 The Titanic Hearings and Aftermath 115 What Happened to the White Star and Cunard Ships? 120 Bonus Article: Remembering Those that Perished At Sea 123 Enjoying Life and the Arts in 1912 Have you ever thought about what life was like 100 years ago? Life has changed considerably in the last 100 years! Today we have numerous forms of entertainment from television, radio, internet, MP3 players, Wii’s, Blackberry’s, Kindles, and a number of other gadgets that keep us entertained. -

DNA Testing Solves Mystery of Titanic Survivor Claim 22 January 2014, by Bob Yirka

DNA testing solves mystery of Titanic survivor claim 22 January 2014, by Bob Yirka liner. Loraine Allison and her mother were both believed lost when the ship sank though neither body was ever recovered. The child's father also died when the ship sank but his body was eventually found. Kramer insisted that she'd been taken in and raised by a man, a fellow passenger in the lifeboat, who explained to her sometime later that she was the missing child. Adding to the sensationalism of the story was Debrina Woods, Helen Kramer's granddaughter who claimed to have physical evidence that her grandmother was who she claimed to be and more recently said she was writing a book about the whole story. That was enough apparently for a group of Titanic aficionados to get together and create what they called the "Loraine Allison Identification Project." That resulted in funding to undertake DNA testing of members of both of the involved families—a great niece of Loraine's mother and Woods' half-sister—the results show absolutely no connection between the two families. The story of the missing toddler took on more Brave Nurse and the Babe She Saved: Alice Cleaver drama when it was revealed that she was believed with Trevor Allison, survivors of the sinking of the RMS to be the only non-adult housed in the first class Titanic after disembarking from the RMS Carpathia section of the boat to have died when the ship sank. Various reports from survivors suggest the family remained on the ship looking for little Loraine's younger brother, who unbeknownst to (Phys.org) —DNA testing has proven that Helen them, had been placed in a lifeboat by a servant. -

Background Data Methods Results Methodological Peer-Review And

A finely stratified log-rank test with effectively-infinite-size comparison groups [ How long did their hearts go on? Survival analysis of the Titanic Survivors ] Background Erroneous analyses in longevity comparisons [Jazz Musicians, Oscar winners] Beyond "who survived": longterm effects Data Passengers ; Comparison Groups Methods Passengers: K-M curves Comparison Groups: "Cohort from Current" (U.S.) & Cohort(Sweden) Lifetables Results Overall; By Gender and Class Methodological Stratified log-rank test: each passenger versus effectively infinite comparison group Peer-review and beyond BMJ ; Media [email protected] http://www.epi.mcgill.ca CASI, May 17-19, 2006 Natural Sciences & Engineering Fonds Québécois de la recherche Research Council of Canada sur la nature et les technologies. Premature Death in Jazz Musicians: Fact or Fiction? commonly held view: More Statistical Study: 70 (82%) of 85 liable than other professions to US-born jazz musicians listed in die early from drink, drugs, university syllabus exceeded women, or overwork. their life expectancy Spencer FJ. Am J Public Health. 1991 81(6):804-5: Am J Public Health. 1992 82(5):761. Longevity of popes and artists between 13th & 19th century Likely, in past centuries, to be Longevity significantly longer better fed, clothed & sheltered, than that of artists (P = 0.02); ... and to had better medical care & artists had 1.5-fold higher risk of to survive longer than most of death before age 70 years than their contemporary people. Popes (95% CI: 1.08–2.16) Serraino D, Carrieri M-P: International Journal of Epidemiology 2005; 34: 1435–1436 Survival in Academy Award–Winning Actors and Actresses Social status is an important Life expectancy 3.9 years longer predictor of poor health. -

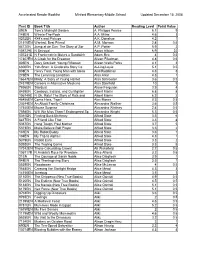

Accelerated Reader Booklist Minford Elementary-Middle School Updated December 15, 2008

Accelerated Reader Booklist Minford Elementary-Middle School Updated December 15, 2008 Test ID Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value 89EN Tom's Midnight Garden A. Philippa Pearce 6.1 9 148EN Winnie-The-Pooh A.A. Milne 4.6 3 8252EN 4X4's and Pickups A.K. Donahue 4.2 1 21516EN Wanted: Best Friend A.M. Monson 2.4 0.5 8472EN Jump at de Sun: The Story of Zor A.P. Porter 5.9 2 108729E N Betrayal Aaron Allston 6.9 22 107241E N Frankenstein Makes a Sandwich Adam Rex 4 0.5 17307EN A Cloak for the Dreamer Aileen Friedman 4.8 0.5 805EN Davy Crockett: Young Rifleman Aileen Wells Parks 4.1 3 6300EN Yeh-Shen: A Cinderella Story fro Ai-Ling Louie 5.1 0.5 808EN Henry Ford: Young Man with Ideas Aird/Ruddiman 4.3 3 276EN The Lemming Condition Alan Arkin 4.3 1 16647EN Minty: A Story of Young Harriet Alan Schroeder 3.6 0.5 24319EN Careers in Alternative Medicine Alan Steinfeld 10 5 7896EN Stardust Alane Ferguson 3.9 4 8459EN Cowboys, Indians, and Gunfighter Albert Marrin 6.8 8 106749E N Oh, Rats! The Story of Rats and Albert Marrin 6.2 2 46456EN Come Here, Tiger! Alex Moran 0.3 0.5 20344EN An Alcott Family Christmas Alexandra Wallner 3.6 0.5 17540EN Mouse Surprise Alexandra Whitney 2.4 0.5 7598EN Will We Miss Them? Endangered Sp Alexandra Wright 5.3 0.5 5361EN Finding Buck McHenry Alfred Slote 3.5 6 5417EN A Friend Like That Alfred Slote 3.3 4 5367EN Hang Tough, Paul Mather Alfred Slote 3.7 5 5373EN Make-Believe Ball Player Alfred Slote 3.3 2 183EN My Robot Buddy Alfred Slote 3.6 1 184EN My Trip to Alpha I Alfred Slote 4.3 1 5379EN Rabbit Ears Alfred -

Hubert Laws Nea Jazz Master (2011)

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. HUBERT LAWS NEA JAZZ MASTER (2011) Interviewee: Hubert Laws (November 10, 1939 - ) Interviewer: Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: March 4-5, 2011 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 134 pp. Brown: Today is March 4th, 2011. This is the Smithsonian NEA Jazz Masters oral history interview with Hubert Laws in his home in Los Angeles, California, conducted by Anthony Brown and Ken Kimery. Good afternoon, Hubert. How are you doing? Laws: I’m fine, man. Brown: The last time I saw you was at the NEA Jazz Masters awards in January. You provided the first musical number, a duet with Kenny Barron, playing Stella by Starlight. I have to say, that was the high point of the evening. It could have stopped after that. That was, oh, incredible. Laws: It’s kind of you to say that, because I felt very good about that collaboration with Kenny. It’s so interesting, because we were supposed to have had a rehearsal that morning. We met in this little room on the side and we ended up – I said, “You know what? Let’s do – let’s just play for a while, and then we’ll lead on into Stella.” I said, “We may do that, or I may do another tune.” He said okay. That’s what I love about professional guys like him. They’re so flexible. We didn’t know what we were going to play in the beginning. -

Titanic Tribute 1912-2012 My Name Is Thomas Mccormack

Mrs. Moore Titanic Tribute 1912- 2012 My name is Margaret Fleming. At the Titanic Tribute st 1912-2012 age of 42, I was a 1 class passenger aboard the Titanic. I was traveling to Haverford, Pennsylvania with my employer, Mrs. Marian Thayer, her husband, Mr. John Thayer, and their son, Mr. John Thayer, Jr. We had spent a long time in Europe and were headed home to Haverford. I boarded Lifeboat 4. Titanic Tribute 1912-2012 My name is Thomas McCormack. When I was 19, I was a 3rd class passenger aboard the Titanic. I was traveling home to New Jersey after visiting my mum back in Ireland. I wasn’t allowed to board a lifeboat so I jumped and swam to one because many were launched half empty. I was traveling with a couple of cousins and was asleep when the accident happened. My name is Captain Edward John Smith. At Titanic Tribute the age of 62, I was the captain of the Titanic. 1912-2012 I was traveling from Southhampton, England without my family. The sailing of the Titanic was going to be my last trip before retiring. Sailing the Titanic and the passengers aside the ocean was suppose to be the greatest adventure of my life. I will always be known as the Captain of the Titanic that lost so many lives when it sank. I did not board a lifeboat and they never found my body. That’s my life as the Captain of the Titanic. Titanic Tribute My name is Annie Sage. I was born in 1867. -

El Barco Fantasma Del 14 De Abril 1912

El barco fantasma del 14 de Abril 1912. Una novela de ficción basada en hechos reales con los detectives Flynn y O’Malley en una de sus últimas aventuras. Javier Torres Landa V. 2015. 1 Advertencia. Flynn y O'Malley son personajes ficticios, y Yo, es el autor de este escrito quien ha decidido utilizar el recurso que ofrecen los relatos de ficción utilizando indistintamente estas denominaciones en el transcurso del relato. Quizá esto cree algunas confusiones y/o problemas de redacción, de ortografía y/o de gramática o hasta de comprensión pero recuerden que nadie es perfecto, ningún escrito es perfecto. Por lo mismo siempre habrá algún aspecto, algún párrafo, alguna referencia que de una forma u otra no se llega a aclarar pero que constituye parte de las intenciones del autor. Las que expresadas en pocas palabras significa el tratar de involucrar al lector de manera que asimile el relato, reflexione sobre sus inconsistencias o defectos pero que en general disfrute de uno de los placeres que nuestra 'era cibernética' amenaza con terminar y que simplemente es que todavía tenemos la oportunidad de leer y hacer uso de nuestra imaginación. 2 1 Uno de los grandes misterios que aún permanecen como incógnita de aquella fatídica noche del 14 al 15 de Abril de 1912 es el reporte de un barco misterioso que los tripulantes del TITÁNIC vieron en las cercanías del trasatlántico una vez que hubieron colisionado con un iceberg, una aparición fantasmagórica (que pudo ser real y a la que no se dio la importancia que debería). -

A Musical Analysis of the Improvisational Bebop Style of Nat Adderley (1955-1964)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music Music, School of 12-2020 A Musical Analysis of the Improvisational Bebop Style of Nat Adderley (1955-1964) Kyle Granville University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Commons Granville, Kyle, "A Musical Analysis of the Improvisational Bebop Style of Nat Adderley (1955-1964)" (2020). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 152. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/152 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A MUSICAL ANALYSIS OF THE IMPROVISATIONAL BEBOP STYLE OF NAT ADDERLEY (1955-1964) by Kyle M. Granville A DOCTORAL DOCUMENT Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor Darryl White Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2020 A MUSICAL ANALYSIS OF THE IMPROVISATIONAL BEBOP STYLE OF NAT ADDERLEY (1955-1964) Kyle M. Granville, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2020 Advisor: Darryl White Nathaniel Carlyle Adderley was an American jazz artist active in New York City, Florida and Europe throughout his extensive musical career. A prominent cornet player and composer, Adderley was highly respected by many of his peers in New York City, Florida, as well as all over Europe. -

And Work Song

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE NAT ADDERLEY (1931-2000) AND WORK SONG: AN ANALYSIS OF IMPROVISATIONAL STYLE AND EVOLUTION A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By MARTIN W. SAUNDERS Norman, Oklahoma 2008 NAT ADDERLEY (1931-2000) AND WORK SONG: AN ANALYSIS OF IMPROVISATIONAL STYLE AND EVOLUTION A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY ___________________________ Dr. Irvin Wagner ___________________________ Dr. Karl Sievers ___________________________ Dr. Eugene Enrico ___________________________ Dr. Eldon Matlick ___________________________ Dr. Alfred Striz © Copyright by MARTIN W. SAUNDERS 2008 All Rights Reserved. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES. vi LIST OF EXAMPLES. vii Chapter I. INTRODUCTION. 1 II. CAREER BIOGRAPHY AND IMPROVISATIONAL STYLE 8 III. TRANSCRIPTION #1 Background. 17 Analysis. 18 Summary. 31 IV. TRANSCRIPTION #2 Background. 35 Analysis. 37 Summary. 49 V. TRANSCRIPTION #3 Background. 55 Analysis. 56 Summary. 67 VI. TRANSCRIPTION #4 Background. 71 Analysis. 72 Summary. 83 VII. TRANSCRIPTION #5 Background. 88 Analysis. 89 Summary. 97 v VIII. COMPARISON/CONTRAST AND SUMMARY OF ANALYZED TRANSCRIPTIONS Evolution of theoretical concepts, improvisatory language, and organizational thought. 102 Conclusions. 111 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY. 113 WORKS CITED. 116 APPENDICES Nat Adderley Biography. 121 Work Song Discography. 123 Discography. 124 Transcription #1. 126 Transcription #2. 128 Transcription #3. 131 Transcription #4. 133 Transcription #5. 135 vi TABLES Table Page 1A - Analyzed 1960 Solo Transcription, p. 1. 33 1B - Analyzed 1960 Solo Transcription, p. 2. 34 2A - Analyzed 1968 Solo Transcription, p. 1. 52 2B - Analyzed 1968 Solo Transcription, p. 2. 53 2C - Analyzed 1968 Solo Transcription, p.