City of Toronto Customized Global Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Corps of Drums Society Newsletter – July 2019

The Corps of Drums Society - Registered Charity No. 1073106 The Corps of Drums Society Registered Charity No. 1073106 Newsletter – July 2019 Committee Contact Information Listed below are the current positions held within the Society, I have also added the relevant email addresses, so if there are specific Areas of concern or information required it will reach the correct person and therefore can be answered in a timely manner Chairman: Roger Davenport [email protected] Hon. Secretary: David Lear MBE [email protected] Hon. Treasurer: Graham (Jake) Thackery [email protected] Drum Major: John Richardson [email protected] Music & Training: Peter Foss [email protected] Training and Development: Iian Pattinson [email protected] Picture archivist: David Lear MBE [email protected] Other Officers Editor, Drummers Call: Geoff Fairfax MBE [email protected] Northern Ireland Rep William Mullen [email protected] Australian Rep Martin Hartley [email protected] Regular Army Liaison Senior DMaj Simon Towe …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. ANNOUNCEMENT – LORD MAYORS SHOW I will require numbers and a breakdown of instrument for all those wishing to take part in this years LMS, I will be sending emails and forms which are to be completed so these can be returned to the pageant master’s PA. Current participants are - Cinque Ports RV COD / St Phillips School COD / Syston Scout & Guide Band / Cheshire Drums & Bugles / Staffordshire ACF COD / Chesham All girls Band / ITC Catterick Drums Course and some individual Society members …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. The Corps of Drums Society - Registered Charity No. 1073106 ANNOUNCEMENT 1 – I have been asked for assistance with s bugler for Remembrance Sunday at St Mary in the Marsh near Dymchurch. -

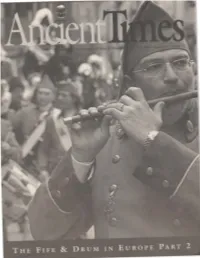

Issue 121 Continues \\~Th Fife .\ Tarry Samp-,On, Wel.T Cojst Editor in Spnill and Drum in Europe, Part 2

PERSONAL • Bus1NESS • TRUST • INVESTMENT SERVICES Offices: Essex, 35 Plains Road. 7o!-2573 • Essex, 9 Main Street, 7o/-&38 Old Saybrook, 15.5 Main Street, 388-3543 • Old Lyme, 101 Halls Road. 434-1646 Member FDIC • Equal Housing Lender www.essexsavings.com 41 EssexFmancialServires Member NA.SD, SIPC Subsidiary of Essex Savings Bank Essex: 176 Westbrook Road (860) 767-4300 • 35 Plains Road (860) 767-2573 Call Toll-Free: 800-900-5972 www.essexfinancialservices.com fNVESTMENTS IN STOCKS. BONDS. MtrT'UAL RJNDS & ANNUITIES: INOT A DEPOSIT INOT FDIC INSURED INOT BANK GUARA,'fl'EED IMAY LOSE VALUE I INOT INSURED BY ANY FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AGENCY I .2 AncientTunes 111t Fifi· rmd Dr11111 l"uc 121 Jul) lXli From the 1 111 Denmark Publt Jied bi Editor The Company of s we're all aware, the 2007 Fifers &Dnmimers 5 muster season is well under http://compan)c1tlifeanddlllm.oii; 111,; Fife n11d tht Dmm A way, fun for all who thrive on Editor: Dan Movbn, Pro Tern in lta(v parades, outdoor music, and fife and Art & ~ign D~ctor. Da,·e Jon~ Advertising Manager: Betty .Moylan drum camaraderie. Please ensure Contributing Editor.Bill .\Wing 7 that there is someone to write up Associate Edi tors: your corps' muster, and that there is Dominkk Cu'-ia, Music Editor Chuck Rik)", Website and Cylx~acc Edimr someone with picrures and captions, .-\m.111dJ Goodheart, Junior XC\1s Editor hoc co submit them co the Ancient ,\I.irk Log.-.don, .\lid,mt Editor Times. Da,c !\ocll, Online Chat Intmicw~ 8 Ed Olsen, .\lo Schoo~. -

Vol-21-Issue-3-Fall-1994.Pdf

... Vol. XXI, No. 3 Fall 1994 $2.50 The Ancient Times P.O. Box 525. Nonprofit Organization U.S. Postage Ivoryton, CT 06442-0525 PAID lvoryton, CT 06442-9998 Permit No. 16 Corps of · chi an on the r uster Field · DATED MATERIAL i mes Fall, 1994 Published by The Company of Fifers & Drummers, Inc. Fort Ticonderoga Musical Weeked by Dan Moylan FORT TICONDEROGA, NY - The Fort Ticonderoga Corps of Drums hosted its third annual "Martial Music Weekend" on July 23rd and 24th. The French built Fort Ticonderoga at the southern end of Lake Champlain in the days of the French and Indian War and called it Fort Carillon. Later taken over by the British, it was captured in May ·or 1775 by Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys and Benedict Arnold leading members of the Connecticut Militia. General Washington sent General Knox to bring the captured artillery pieces by ox train 300 miles to Boston, where they were emplaced on Dorchester Heights and after a short bombardment persuaded the Fifers of the Swiss Colonials of Switzerland and the Kentish Guards of Rhode Island British to evacuate Boston. Though The Ancient Times join in musical .friendship to conclude the Museum's first concert program of the in South Boston the Irish celebrate season on July 5 in Ivoryton, Cf. the 17th of March as St. Patrick's Earns Graphic.Award Day, the local Yankees still celebrate DEEP RIVER, CT - "For Evacuation Day. outstanding achievement in the The Tittabawasse Valley Fife and graphic arts" The Ancient Times has Fusileers May Muster Success Drum Corps of Midland, Michigan won its first professional recognition interludes as passers-by tripped. -

The Ancient Times

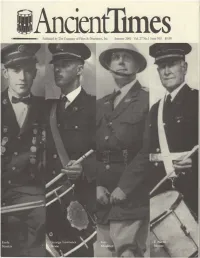

' The Ancient Times < +WIBHM Published by The Company of Filers & Drummers! Inc. Mi 1- Vol. XII No. One Dollar and Twenty-Five Cents Summer/985 Frank Orsini Installed As Sixth President Frank Orsini of Rahway, New Jersey, noly, The Windsor Fife and Drum Art Auction To Benefit Ancients Fund a member of the New Jersey Colonial Corps of Windsor, CT directed by Fran Militia Fife and Drum Corps, was Dillon, formerly with the Sgt. Bissell A Success elected and installed as the sixth Presi- Corps, The Connecticut Colonials of dent of The Company of Fifers and Hebron under the direction of Bill The Art Auction for the benefit o( of Richmond Hill, New York and Gus Drummers at the Annual Meeting held Ryan, and the 8th CT Volunteers of Ancients' Fund, held at The Company's Cuccia of the Young Colonials of in The Company's headquarters in Manchester. Headquarters on May 4, was termed a Carmel, New York travelled the greatest Ivoryton, April 13. Before relinquishing the Chair, outgo- success by both Marlin Art, Inc. who of- distance to attend. The ladies of the Jr. Other Administrative Officers elected ing President Eldrick Arsenault, on feredthepiecesofart,andtheCommit- ·colonialsofWestbrookdidyeomandu- are Roger Clark of the Deep River behalf of The Company, presented a tee from The Company of Fifers and ty handling "the bank" and serving the Drum Corps, First Vice President; Moe plaque with a clock to Registrar Drummers who did all the necessary wine and cheese all evening. The door Schoos of the Kentish Guards Fife and Emeritus Foxee Carlson in appreciation work before, during and after the auc- prize, a winter farm scene was won by Drum Corps, Second Vice President; of his twenty year term as the Registrar Phil Truitt of the New Jersey Colonial of The Company. -

Collection P18 Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry Band Photograph Collection

Collection P18 Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry Band photograph collection. – 1914-[ca. 1990]. – Ca. 120 photographs. P18.1(5)-1 PPCLI Pipe Band at Bruay, France, prior to Battle of Vimy Ridge. Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry had two bands during the First World War. The Edmonton Pipe Band joined as a unit in August 1914. Pipers played men over the top and then followed as stretcher-bearers. The core of the PPCLI Brass and Reed Band was formed when eligible members of The St. Mary’s Boys Brigade Band joined the 140th New Brunswick Battalion in January 1916. When the 140th was broken up in November 1917, the entire Band joined PPCLI in the field. Bandmaster (Lance Sergeant) Charles H. Williams was wounded in the front lines near Tilloy, France 28 September 1918 and later died. His brother, Sergeant Harold H. (Pete) Williams took over as Bandmaster for the duration of the war. Both bands provided music during route marches, burials and rest periods. The PPCLI Band performed one of its last official duties on 27 February 1919 when it played at Princess Patricia’s wedding. When the Permanent Force was established in 1919, the PPCLI Military Band was reformed. Under the guidance of Captain Tommy James, it was stationed at Fort Osborne Barracks in Winnipeg during the 1920s and 1930s. It played as many as 50 free concerts a year and was broadcast across Canada. Around 1935 the PPCLI Bugle Band was formed and then a Dance Band was formed ca.1937. When James retired in 1939, Warrant Officer I Al Streeter took over as Director of Music. -

006-013, Chapter 1

trumpeteers or buglers, were never called bandsmen. They had the military rank, uniform and insignia of a fifer, a drummer, a d trumpeteer or a bugler. d Collectively, they could be called the fifes l l & drums, the trumpets & drums, the drum & bugle corps, the corps of drums, the drum e e corps, or they could be referred to simply as i the drums in regiments of foot or the i trumpets in mounted units. f f Since the 19th century, the United States military has termed these soldier musicians e the “Field Music.” This was to distinguish e them from the non-combatant professional l l musicians of the Band of Music. The Field Music’s primary purpose was t t one of communication and command, t whether on the battlefield, in camp, in t garrison or on the march. To honor the combat importance of the Field Music, or a a drum corps, many armies would place their regimental insignia and battle honors on the b drums, drum banners and sashes of their b drum majors. The roots of martial field music go back to ancient times. The Greeks were known to e have used long, straight trumpets for calling e Chapter 1 commands (Fig. 1) and groups of flute players by Ronald Da Silva when marching into battle. h h The Romans (Fig. 2 -- note the soldier When one sees a field performance by a with cornu or buccina horn) used various t t modern drum and bugle corps, even a unit as metal horns for different commands and military as the United States Marine Drum & duties. -

The Corps of Drums Society Newsletter – June 2019

The Corps of Drums Society - Registered Charity No. 1073106 The Corps of Drums Society Registered Charity No. 1073106 Newsletter – June 2019 Committee Contact Information Listed below are the current positions held within the Society, I have also added the relevant email addresses, so if there are specific Areas of concern or information required it will reach the correct person and therefore can be answered in a timely manner Chairman: Roger Davenport [email protected] Hon. Secretary: David Lear MBE [email protected] Hon. Treasurer: Graham (Jake) Thackery [email protected] Drum Major: John Richardson [email protected] Music & Training: Peter Foss [email protected] Training and Development: Iian Pattinson [email protected] Picture archivist: David Lear MBE [email protected] Other Officers Editor, Drummers Call: Geoff Fairfax MBE [email protected] Northern Ireland Rep William Mullen [email protected] Australian Rep Martin Hartley [email protected] Regular Army Liaison Senior DMaj Simon Towe …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. ANNOUNCMENT - 10th Leicester (1st SYSTON) Scout & Guide Band COD Received from Pam Hales - I write with great sadness to say we have lost a 'brother', Scout Leader, and Bugle Instructor in excess of 25yrs for 10th Leicester, (1st Syston) Scout & Guide Band, Group, and always as part of our yearly contingent of members who have proudly taken part with the massed band of the 'Corps of Drums Society' every year, for 20 years, in the annual London, Lord Mayors Parade. David Andrew Lucas aged 39yrs passed away on Saturday 25th May 2019. The Corps of Drums Society - Registered Charity No. 1073106 David progressed through all units of Syston Scouts, attaining the 'Queens Scout Award' and eventually trained to become a Beaver Scout Leader, teaching the youngest boys and girls to 'join up' and learn all the best 'lessons in life', by a volunteered, time served, loyal Scout Leader. -

E Household Division Presents E Sword & E Crown a Military Musical

!e Household Division Presents !e Sword & !e Crown A Military Musical Spectacular Horse Guards Parade London 20!ff - 22#$ July 2021 Foreword Major General C J Ghika CBE %e Sword & %e Crown is a musical spectacular, showcasing some of the most talented military musicians in the British Army. We are extremely pleased to welcome back the Bands of the Grenadier, Coldstream, Scots, Irish & Welsh Guards with the Corps of Drums of the 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards to Horse Guards for the &rst time since %e Queen’s Birthday Parade in 2019. %e Massed Bands of the Household Division are also joined by the Band of the Honourable Artillery Company, the Band of %e Royal Yeomanry, %e Pipes & Drums of the London Scottish Regiment, the Corps of Drums of the Honourable Artillery Company and the Combined Universities’ O'cer Training Corps Pipes and Drums. We hope %e Sword & %e Crown will bring a much-needed lift to the country’s spirits after a challenging year and a half, endured by all. %ose that you see on parade today not only represent the musician talent of the British Army but also the breadth of roles the military provides; in the last sixteen months the British Army has been focused on supporting the National Health Service in the &ght against COVID-19 and some of those on parade today will have been involved in that &ght. We have all learnt to adapt recently to changing rules and regulations, and the British Army is no di(erent, in particular when it comes to State Ceremonial events. -

1 Army Policy & Secretariat Army Headquarters IDL 24 Blenheim

Army Policy & Secretariat Army Headquarters IDL 24 Blenheim Building Marlborough Lines Andover Hampshire, SP11 8HJ United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] Ref: Army/Sec/Infra/FOI2021/03746 Website: www.army.mod.uk Mr J Zacchi request-744978- 28 April 2021 [email protected] Dear Mr Zacchi, Thank you for your email of 07 April 2021 in which you requested the following: Could you provide: A) List of the current Army Reserve bands. B) Role of Army Reserve bands (if available to release) C) Do the Army Reserve bands report to CAMUS for administration, or do they only report to the RHQ/Battalion HQ? I am treating your correspondence as a request for information under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (the Act). I have addressed each of your three requests individually, below: A) List of current Army Reserve bands The Band of 150 Regiment Royal Logistics Corps The Band of The Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment Army Medical Services Band The Band of The Royal Yeomanry (Inns of Court & City Yeomanry) The Honourable Artillery Company Regimental Band The Lancashire Artillery Band The Band of the Mercian Regiment Nottinghamshire Band of the Royal Engineers The Band of The Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment The Band of the Royal Anglian Regiment The Band of the Royal Irish Regiment The Royal Signals (Northern) Band The Regimental Band & Corps of Drums of The Royal Welsh The Salamanca Band and Bugles of The Rifles The Waterloo Band and Bugles of The Rifles The Band of the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers The Highland Band of The Royal Regiment of Scotland The Lowland Band of The Royal Regiment of Scotland The Band of the Yorkshire Regiment B) Role of the Army Reserve bands Army Reserve Bands provide musical support to Defence tasks. -

Published by the Company of Fifers & Drummers, Inc. October 2005 Issue

• aen Published by The Company of Fifers & Drummers, Inc. October 2005 Issue 116 $5.00 PERSONAL • BUSINESS • TRUST • INVESTMENT SERVICES Offices: Essex, 35 Plains Road, 7o7-2573 • Essex, 9 Main Street, 7o7-S238 Old Saybrook, 155 Main Street, 388-3543 • Old Lyme, 101 Halls Road, 434-1646 Member FDIC • Equal Housing Lender www.essexsavings.com 41 EssexFmancialServices Member NA.SD, SIPC Subsidiary of Essex Savings Bank Essex: 176 Westbrook Road (860) 767-4300 • 35 Plains Road (860) 767-2573 Call Toll-Free: 800-900-5972 www.essexfinancialservices.com INVESTMENTS IN STOCKS. BONDS. '\.iUTIJAL Fl.NOS & ANNUITrES: Ir-or A DEPOSIT jr-or ro1c 1ssLRED! r-oT BA:-IK GuARA;\;TEED !MAY LOSE VALuEj jsor ,~sL'RED sv ~" FEDERALGOVER~\1C~T AGE.'\CY I Ancienffimes 2 From the Editor 1 Im~ I U,, 0,1,i«r !005 THE PERFECTIONISTS· Published by The History ofRudi mental Snare he theme of this issue is the 40th Anniversary The Company of Drnmming: Part 2 Year of The Company ofFifers & Drummers. It's been a great 40 yean., and we've come a Fifers & D rummers 6 long way. I'm sure you will all enjoy the arti hup/k'ompanyoffire.wklnim.org Dmms Along the Maumee cle presenting the minutes of our founding f.dllor: Editor: Dan JfQJlan, Pro Tm, Tmeeting in I 965. Which of us knew that the original name An & Design Dirtctor: Da\t Jone,; 8 of the organization had been decided as "The Committee of Ad1erming Managtt: uoBrtnnan Roy! Fifers & Drummers''? According to Pace ·s minutes, there A$!illdalt Edltorl: Dormnicl Cuccia. -

Issue 103 SS.00 40TH ANNIVERSARY

Published by The Company ofFifers & Drummers, Inc. Summer 2001 Vol. 27 No.l Issue 103 SS.00 40TH ANNIVERSARY HanJcrafteJ Cooperman rope lerMion f ie!J drurn1. Fulldervice drum dhop for repair, r&Jtoration, par&,anJ duppUM. T HE C OOPERi\llAN C OMPANY A <1eco11d-ge1uration family 6uc1uu4J commilteiJ lo traoilionnf cm/t.mznn,1hip and tiuwvative Je.,ign &,1e.:1: I11iJwtrial Park, P.O. &.i: 276, Ce11ter6r"ok1 CT 06409-0276 USA Tel: 860-767-1779 Fa..i:: 860-767-70/7 Email: [email protected] On the We6: 11•u•w.cooperma11.co111 2 Ancienffimes The Drum From the 1 :--o. 1o3- Sunm>tf 2001 l'ublt1hrJ bv 3 Publisher/Editor The Co_mpany of Fifers fsDrummers This is.sue of the Ancient Times features "The 4 Drum" -some makers, some players, some Editor: Bob Lynch. cnw. [email protected] The Fife and Drum in the teachers and some history. As a boy 1 was fas Senior Editor: Robin N1rnuti, Netherlands muil: RN1muu'aprodifl> .nn cinated by the sounds of the drum. There was nothing more thrilling than the rhythmic drum Assoc:ia~ E.diton: T Mllt}· Smipion, Wt1t ~ Aoocutc F..htor beats in the pit of my stomach when a drum line of a S!l"\·r :--."ICIIUCZ, CiJmd.r marching band ~ by. What the drum was then, it is EJ Obm, Mo Sd,oo,, ObmmttS 6 for me today -a fascinating instrument with a long history George i.Awrence Stone Art a Desig,, Director: 0.1\'r )Oll<S in many ancient and modem civilization around the world. -

BLUE PLUME the Music of the Irish Guards

BLUE PLUME The Music of the Irish Guards BAND OF THE IRISH GUARDS Director of Music: Major Bruce Miller BMus (Hons) LLCM (TD) LRSM ARCM psm FOREWORD COLONEL OF THE REGIMENT HRH PRINCE WILLIAM, DUKE OF CAMBRIDGE KG KT ADC THE DIRECTOR OF MUSIC: BANDMASTER: MAJOR BRUCE MILLER BMus (Hons) LLCM (TD) LRSM ARCM psm WARRANT OFFICER CLASS ONE ANDREW WILLIAM PORTER BMus (Hons) FTCL Major Bruce Miller began his military career in 1989 as a clarinettist in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps. Upon successful completion of the three-year Bandmaster Course Andrew Porter was born in Belfast enlisting into the Army in 2003 as a euphonium he was appointed Bandmaster of the Band of The Dragoon Guards followed by Staff player, serving with the REME Band. He was invited to Washington DC in 2006 to perform Bandmaster at Headquarters Corps of Army Music. He was commissioned in 2002 recitals at the United States Army Band Tuba and Euphonium Conference, returning in and appointed Director of Music of the Band of the Hussars and Light Dragoons, 2007 to perform a concerto in the presence of the composer, Neal Corwell, with the which upon amalgamation became the Light Cavalry Band before taking up his next United States Army Orchestra. appointment as Director of Music, Band of the Corps of Royal Engineers. His first assignment as a Bandmaster was to the Band of The King’s Appointments at Headquarters Corps of Army Music along with Chief Division from where he deployed on Op HERRICK 18 in 2013 and Instructor of the Royal Military School of Music combined with a tour at was assigned to the Afghan National Army Officers Academy the Minden Band of the Queen’s Division before taking up his current (ANAOA) in Qargha, Kabul.