Smuggling of Migrants a Global Review and Annotated Bibliography of Recent Publications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Submitted for the Phd Degree at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London

THE CHINESE SHORT STORY IN 1979: AN INTERPRETATION BASED ON OFFICIAL AND NONOFFICIAL LITERARY JOURNALS DESMOND A. SKEEL Submitted for the PhD degree at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 1995 ProQuest Number: 10731694 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731694 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 A b s t ra c t The short story has been an important genre in 20th century Chinese literature. By its very nature the short story affords the writer the opportunity to introduce swiftly any developments in ideology, theme or style. Scholars have interpreted Chinese fiction published during 1979 as indicative of a "change" in the development of 20th century Chinese literature. This study examines a number of short stories from 1979 in order to determine the extent of that "change". The first two chapters concern the establishment of a representative database and the adoption of viable methods of interpretation. An important, although much neglected, phenomenon in the make-up of 1979 literature are the works which appeared in so-called "nonofficial" journals. -

China Assessment October 2001

CHINA COUNTRY ASSESSMENT October 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit CONTENTS 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 2. GEOGRAPHY 2.1 - 2.26 Geographical area 2.1 - Jiangxi province 2.2 - 2.16 Population 2.17 Names / Surnames / clan names 2.18 - 2.20 Language 2.21 - 2.26 3. HISTORY 3.1 –3.54 pre-1993: 3.1 - 3.2 1966-76 Cultural Revolution 3.3 - 3.5 1978-89 and economic reform 3.6 - 3.9 1989 Tiananmen Square 3.10 - 3.12 Post-Tiananmen 3.13 -3.14 1993-present: 3.15 - 3.33 Crime and corruption 3.15 - 3.24 Criminal activity 3.25 - 3.28 Government leadership 3.29 Economic reform 3.30 - 3.34 Currency 3.35 1999: Anniversaries 3.36 - 3.37 International relations 3.38 - 3.39 "One country, two systems" issues 3.40 - 3.54 Relations with Taiwan 3.40 - 3.43 Hong Kong: 3.44 - 3.46 Elections 3.47 Dissidence 3.48 -3.50 Mainland born children 3.51 Vietnamese boat people 3.52 Macao 3.53 - 3.54 IV: INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE 4.1 - 4.49 Government and the Constitution 4.1 - 4.20 Political structure 4.4 General overview 4.6 - 4.10 Village committees 4.11 - 4.19 Neighbourhood committees 4.20 Legal framework 4.21 Criminal Law 4.23 Criminal Procedure Law 4.25 State Compensation Law 4.25 Regulation changes 4.28 Appeals 4.29 Land law 4.34 Security situation 4.37 - 4.33 Shelter and investigation 4.38 Re-education through labour 4.39 Police 4.40 - 4.46 Armed Forces, Military conscription and desertion 4.47 - 4.49 5. -

Characteristics of Chinese Human Smugglers: a Cross-National Study, Final Report

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Characteristics of Chinese Human Smugglers: A Cross-National Study, Final Report Author(s): Sheldon Zhang ; Ko-lin Chin Document No.: 200607 Date Received: 06/24/2003 Award Number: 99-IJ-CX-0028 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. THE CHARACTERISTICS OF CHINESE HUMAN SMUGGLERS ---A CROSS-NATIONAL STUDY to the United States Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice Grant # 1999-IJ-CX-0028 Principal Investigator: Dr. Sheldon Zhang San Diego State University Department of Sociology 5500 Campanile Drive San Diego, CA 92 182-4423 Tel: (619) 594-5449; Fax: (619) 594-1325 Email: [email protected] Co-Principal Investigator: Dr. Ko-lin Chin School of Criminal Justice Rutgers University Newark, NJ 07650 Tel: (973) 353-1488 (Office) FAX: (973) 353-5896 (Fa) Email: kochinfGl,andronieda.rutgers.edu- This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

China, Country Information

China, Country Information CHINA COUNTRY ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VIA HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB HUMAN RIGHTS: SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC HUMAN RIGHTS: OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX D: GLOSSARIES ANNEX E: CHECKLIST OF CHINA INFORMATION PRODUCED BY CIPU ANNEX F: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. GEOGRAPHY file:///V|/vll/country/uk_cntry_assess/apr2003/0403_China.htm[10/21/2014 9:56:46 AM] China, Country Information Geographical Area 2.1. The People's Republic of China (PRC) covers 9,571,300 sq km of eastern Asia, with Mongolia and Russia to the north; Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakstan to the north-west; Afghanistan and Pakistan to the west; India, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam to the south; and Korea in the north-east. -

Why Immigrants Benefit the United States Economy and the Legal and Tax Issues Chinese, Filipinos and Vietnamese Face When Immigrating to the U.S

Golden Gate University School of Law GGU Law Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 4-14-2016 Why Immigrants Benefit the nitU ed States Economy and the Legal and Tax Issues Chinese, Filipinos and Vietnamese Face When Immigrating to the U.S. Marc Santamaria Golden Gate University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/theses Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Immigration Law Commons Recommended Citation Santamaria, Marc, "Why Immigrants Benefit the nitU ed States Economy and the Legal and Tax Issues Chinese, Filipinos and Vietnamese Face When Immigrating to the U.S." (2016). Theses and Dissertations. Paper 67. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOLDEN GATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW ÈÈÈÈÈ Why Immigrants Benefit the United States Economy and the Legal and Tax Issues Chinese, Filipinos and Vietnamese Face When Immigrating to the U.S. Attorney Marc Santamaria, J.D., LL.M. S.J.D. Candidate ÈÈÈÈÈ SUBMITTED TO THE GOLDEN GATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW, DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL LEGAL STUDIES, IN FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE CONFERMENT OF THE DEGREE OF SCIENTIAE JURIDICAE DOCTOR (SJD). Professor Dr. Christian Nwachukwu Okeke Professor Dr. Remigius Chibueze Professor Dr. Gustave Lele SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA April 14, 2016 Acknowledgments To our God and Father be glory for ever and ever. -

Gender and Organized Crime

UNIVERSITY MODULE SERIES MODULE 15 GENDER AND ORGANIZED CRIME UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME EDUCATION FOR JUSTICE UNIVERSITY MODULE SERIES Organized Crime Module 15 GENDER AND ORGANIZED CRIME UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2019 This Module is a resource for lecturers. Developed under the Education for Justice (E4J) initiative of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), a component of the Global Programme for the Implementation of the Doha Declaration, this Module forms part of the E4J University Module Series on Organized Crime and is accompanied by a Teaching Guide. The full range of E4J materials includes university modules on integrity and ethics, crime prevention and criminal justice, anti-corruption, trafficking in persons / smuggling of migrants, firearms, cybercrime, wildlife, forest and fisheries crime, counter-terrorism as well as organized crime. All the modules in the E4J University Module Series provide suggestions for in-class exercises, student assessments, slides and other teaching tools that lecturers can adapt to their contexts, and integrate into existing university courses and programmes. The Module provides an outline for a three-hour class, but can be used for shorter or longer sessions. All E4J university modules engage with existing academic research and debates, and may contain information, opinions and statements from a variety of sources, including press reports and independent experts. Terms and conditions of use of the Module can be found on the E4J website. © United Nations, April 2019. All rights reserved, worldwide. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Country of Origin Information Report: China October 2003

China, Country Information Page 1 of 148 CHINA COUNTRY REPORT OCTOBER 2003 COUNTRY INFORMATION & POLICY UNIT I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VIA HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB HUMAN RIGHTS: SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC HUMAN RIGHTS: OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX D: GLOSSARIES ANNEX E: CHECKLIST OF CHINA INFORMATION PRODUCED BY CIPU ANNEX F: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1. This report has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2. The report has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3. The report is referenced throughout. It is intended for use by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. http://www.ind.homeoffice.gov.uk/ppage.asp?section=168&title=China%2C%20Country%20Information 11/17/2003 China, Country Information Page 2 of 148 1.4. It is intended to revise the reports on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. -

Migrant Smuggling in Asia

Migrant Smuggling in Asia An Annotated Bibliography April 2012 2 Knowledge Product: MIGRANT SMUGGLING IN ASIA An Annotated Bibliography Printed: Bangkok, April 2012 Authorship: United Nations O!ce on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Copyright © 2012, UNODC e-ISBN: 978-974-680-330-4 "is publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-pro#t purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNODC would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations O!ce on Drugs and Crime. Applications for such permission, with a statement of purpose and intent of the reproduction, should be addressed to UNODC, Regional Centre for East Asia and the Paci#c. Cover photo: Courtesy of OCRIEST Product Feedback: Comments on the report are welcome and can be sent to: Coordination and Analysis Unit (CAU) Regional Centre for East Asia and the Paci#c United Nations Building, 3 rd Floor Rajdamnern Nok Avenue Bangkok 10200, "ailand Fax: +66 2 281 2129 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.unodc.org/eastasiaandpaci#c/ UNODC gratefully acknowledges the #nancial contribution of the Government of Australia that enabled the research for and the production of this publication. Disclaimers: "is report has not been formally edited. "e contents of this publication do not necessarily re$ect the views or policies of UNODC and neither do they imply any endorsement. -

Transnational Migration Brokerage in Southern China

> underworlds & borderlands brokering migration from southern china The income gap between rich and developing countries is still the most influential factor driving transnational migration. Although strict border controls and selection criteria have erected barriers, thousands of people who do not meet the requirements have reached their destinations, while even greater numbers would like to do so. As individual effort cannot ensure successful cross-border migration, its brokerage has become a profitable business. Li Minghuan obtain permanent residency upon arriv- for her assistance, she received rewards snakeheads’: small groups (like Sister Most difficult, and thus most expen- al based on family ties or were granted of appreciation, but soon it became an Ping’s) who legally live abroad and use sive, is acquiring official immigra- y research focuses on Tingjiang, work permits and settled down; others open secret that ‘it takes money to buy large sums of money to ‘pave the way tion status, but if the applicant agrees Ma rural region along the south- went to Hong Kong where opportuni- every step of emigration’. In Tingjiang out’ of China and into the destination to go abroad as a contract worker to east coast of China known for decades ties were plentiful and wages much in the mid-1980s, the quoted price for country. They organise and expand tran- countries such as Israel or Kuwait, the as a source area of transnational migra- higher than in the PRC. News from the helping a person emigrate to the U.S. snational migration networks, take care charge will be lower. Third, it depends tion. -

Interdependency and Commitment Escalation As Mechanisms of Illicit Network Failure

Global Crime ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fglc20 Cumulative disruptions: interdependency and commitment escalation as mechanisms of illicit network failure Michelle D. Fabiani & Brandon Behlendorf To cite this article: Michelle D. Fabiani & Brandon Behlendorf (2020): Cumulative disruptions: interdependency and commitment escalation as mechanisms of illicit network failure, Global Crime, DOI: 10.1080/17440572.2020.1806825 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17440572.2020.1806825 View supplementary material Published online: 01 Sep 2020. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fglc20 GLOBAL CRIME https://doi.org/10.1080/17440572.2020.1806825 ARTICLE Cumulative disruptions: interdependency and commitment escalation as mechanisms of illicit network failure Michelle D. Fabiani a and Brandon Behlendorfb aDepartment of Social Sciences, Homeland Security Program,DeSales University, Center Valley, PA, USA; bCollege of Emergency Preparedness, Homeland Security, and Cybersecurity, University at Albany (State University of New York), Albany, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Disruptions can take many forms resulting from both internal and Received Rxx xxxx xxxx external tensions. How illicit networks fail to adapt to a wide range Accepted Axx xxxx xxxx of disruptions is an important but understudied area of network KEYWORDS analysis. Moreover, disruptions can be cumulative, constraining the Criminal networks; network possible set of subsequent adaptations for a network given pre failure; escalation of vious investments. Drawing from a multi-national/multi-year inves commitment; tigation of a prominent Chinese human smuggling network interdependency; human operated by Cheng Chui Ping (‘Sister Ping’), we find that the net smuggling; cumulative work’s failure was a product of two interrelated factors. -

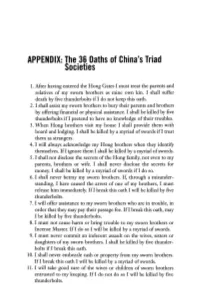

APPENDIX: the 36 Oaths of China's Triad Societies

APPENDIX: The 36 Oaths of China's Triad Societies 1. Mter having entered the Hong Gates I must treat the parents and relatives of my sworn brothers as mine own kin. I shall suffer death by five thunderbolts if I do not keep this oath. 2. I shall assist my sworn brothers to bury their parents and brothers by offering financial or physical assistance. I shall be killed by five thunderbolts if I pretend to have no knowledge of their troubles. 3. When Hong brothers visit my house I shall provide them with board and lodging. I shall be killed by a myriad of swords if I treat them as strangers. 4. I will always acknowledge my Hong brothers when they identify themselves. If I ignore them I shall be killed by a myriad of swords. 5. I shall not disclose the secrets of the Hong family, not even to my parents, brothers or wife. I shall never disclose the secrets for money. I shall be killed by a myriad of swords if I do so. 6. I shall never betray my sworn brothers. If, through a misunder standing, I have caused the arrest of one of my brothers, I must release him immediately. If I break this oath I will be killed by five thunderbolts. 7. I will offer assistance to my sworn brothers who are in trouble, in order that they may pay their passage fee. If I break this oath, may I be killed by five thunderbolts. 8. I must not cause harm or bring trouble to my sworn brothers or Incense Master. -

China – PLA – Conscription – Dissidents – Taiwan – Passports

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: CHN17423 Country: China Date: 8 July 2005 Keywords: China – PLA – Conscription – Dissidents – Taiwan – Passports This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Can you provide information on the PLA – are you conscripted, do you volunteer, and how do you leave the PLA, etc? 2. Please provide any information on treatment of dissidents in the Army. 3. Please provide any information on Taiwanese passports and the availability of false Taiwan passports. List of Sources Consulted Internet Sources: Government Information & Reports Bureau of Consular Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Taiwan http://www.boca.gov.tw/english/index.htm Criminal Investigation Bureau, Taiwan http://www.cib.gov.tw/english/index.aspx Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the United States of America http://www.china-embassy.org/eng/ Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada http://www.irb.gc.ca/cgi- bin/foliocgi.exe/refinfo_e UK Home Office http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk US Department of State http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk United Nations (UN) UNHCR http://www.unhcr.ch/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/home Non-Government Organisations Amnesty International http://www.amnesty.org/ Global Security http://www.globalsecurity.org/