Scriabin in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RICHARD STRAUSS Composer Biography

RICHARD STRAUSS Composer Biography Richard Strauss (June 11, 1864–September 8, 1949) was a German composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras. Born into a family of musicians, he received a formal music education from his father and wrote his first composition at the age of six. He heard his first Wagner operas in 1874; the composer would go on to hugely influence Strauss’s style. He became the Music Director in Meiningen at the age of 21 and, a year later, the Musical Director at the Munich Court Opera. 1886 saw the peak of his skill at orchestration. In 1889, he moved to Weimar and became 2nd Kappelmeister. He married soprano Pauline de Ahna in 1894. Salome premiered in 1905, and Strauss became known as the father of modern opera music. His operas during this time were met with extremely mixed reactions. Elektra, like Salome, was considered extremely risqué by critics. After World War I, Strauss’s fortune was confiscated as “enemy assets”. He began to compose Lieder again during this time. In 1919, he was appointed Vienna State Opera Music Director and fought against its image as an outdated institution that produced only traditional operas by bringing new productions to the opera house. Wishing to confront the bleakness of the post-war era with cultural beauty, he helped to co-found the Salzburg Festival in 1920. He also toured in the USA and South America during this time. The interwar period saw the production of more light-hearted tunes and musical comedies. This is a stark contrast to the following period in which he was made President of the German State Music Bureau “Reichsmusikkammer” in 1933. -

Kostka, Stefan

TEN Classical Serialism INTRODUCTION When Schoenberg composed the first twelve-tone piece in the summer of 192 1, I the "Pre- lude" to what would eventually become his Suite, Op. 25 (1923), he carried to a conclusion the developments in chromaticism that had begun many decades earlier. The assault of chromaticism on the tonal system had led to the nonsystem of free atonality, and now Schoenberg had developed a "method [he insisted it was not a "system"] of composing with twelve tones that are related only with one another." Free atonality achieved some of its effect through the use of aggregates, as we have seen, and many atonal composers seemed to have been convinced that atonality could best be achieved through some sort of regular recycling of the twelve pitch class- es. But it was Schoenberg who came up with the idea of arranging the twelve pitch classes into a particular series, or row, th at would remain essentially constant through- out a composition. Various twelve-tone melodies that predate 1921 are often cited as precursors of Schoenberg's tone row, a famous example being the fugue theme from Richard Strauss's Thus Spake Zararhustra (1895). A less famous example, but one closer than Strauss's theme to Schoenberg'S method, is seen in Example IO-\. Notice that Ives holds off the last pitch class, C, for measures until its dramatic entrance in m. 68. Tn the music of Strauss and rves th e twelve-note theme is a curiosity, but in the mu sic of Schoenberg and his fo ll owers the twelve-note row is a basic shape that can be presented in four well-defined ways, thereby assuring a certain unity in the pitch domain of a composition. -

An Examination of Stylistic Elements in Richard Strauss's Wind Chamber Music Works and Selected Tone Poems Galit Kaunitz

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 An Examination of Stylistic Elements in Richard Strauss's Wind Chamber Music Works and Selected Tone Poems Galit Kaunitz Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC AN EXAMINATION OF STYLISTIC ELEMENTS IN RICHARD STRAUSS’S WIND CHAMBER MUSIC WORKS AND SELECTED TONE POEMS By GALIT KAUNITZ A treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Galit Kaunitz defended this treatise on March 12, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Eric Ohlsson Professor Directing Treatise Richard Clary University Representative Jeffrey Keesecker Committee Member Deborah Bish Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii This treatise is dedicated to my parents, who have given me unlimited love and support. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee members for their patience and guidance throughout this process, and Eric Ohlsson for being my mentor and teacher for the past three years. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ vi Abstract -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 © Copyright by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age by Ryan Isao Rowen Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Mitchell Bryan Morris, Chair The Silver Age has long been considered one of the most vibrant artistic movements in Russian history. Due to sweeping changes that were occurring across Russia, culminating in the 1917 Revolution, the apocalyptic sentiments of the general populace caused many intellectuals and artists to turn towards esotericism and occult thought. With this, there was an increased interest in transcendentalism, and art was becoming much more abstract. The tenets of the Russian Symbolist movement epitomized this trend. Poets and philosophers, such as Vladimir Solovyov, Andrei Bely, and Vyacheslav Ivanov, theorized about the spiritual aspects of words and music. It was music, however, that was singled out as possessing transcendental properties. In recent decades, there has been a surge in scholarly work devoted to the transcendent strain in Russian Symbolism. The end of the Cold War has brought renewed interest in trying to understand such an enigmatic period in Russian culture. While much scholarship has been ii devoted to Symbolist poetry, there has been surprisingly very little work devoted to understanding how the soundscape of music works within the sphere of Symbolism. -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2015-2016 Mellon Grand Classics Season June 10 and 12, 2016 GIANCARLO GUERRERO, CONDUCTOR SERGEI PROKOFIEV Suite from Lieutenant Kijé, Opus 60 I. The Birth of Kijé II. Romance III. Kijé’s Wedding IV. Troika V. The Burial of Kijé AARON COPLAND El Salón México Intermission THE EARTH – AN HD ODYSSEY RICHARD STRAUSS Also sprach Zarathustra, Opus 30 JOHN ADAMS Short Ride in a Fast Machine June 10-12, 2016, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA SERGEI PROKOFIEV Born 23 April 1891 in Sontsovka, Russia; died 4 March 1953 in Moscow Suite from Lieutenant Kijé, Opus 60 (1933-1934) PREMIERE OF WORK: Moscow, 21 December 1934; Soviet State Radio Orchestra; Sergei Prokofiev, conductor PSO PREMIERE: 7 January 1944; Syria Mosque; Fritz Reiner, conductor APPROXIMATE DURATION: 19 minutes INSTRUMENTATION: woodwinds in pairs plus piccolo, tenor saxophone, four horns, cornet, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, percussion, harp, celesta, piano and strings Lieutenant Kijé, directed by Alexander Feinzimmer, was a portrait of early-19th-century Russia and a satire on government bungling and militarism. Russian-born American scholar Nicholas Slonimsky described the plot: “The subject of the film is based on an anecdote about Czar Nicholas I, who misread the report of his military aid so that the last syllable of the name of a Russian officer which ended ki and the Russian expletive jé formed a non-existent name, Kijé. The obsequious courtiers, fearful of pointing out to the Czar the mistake he had made, decided to invent an officer of that name. Hence all kinds of comical adventures and fictitious occurrences.” The mythical soldier was really a blessing in disguise, since the blame for any bureaucratic bungling could be dumped on his head. -

Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin

Analysis of Scriabin’s Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) was a Russian composer and pianist. An early modern composer, Scriabin’s inventiveness and controversial techniques, inspired by mysticism, synesthesia, and theology, contributed greatly to redefining Russian piano music and the modern musical era as a whole. Scriabin studied at the Moscow Conservatory with peers Anton Arensky, Sergei Taneyev, and Vasily Safonov. His ten piano sonatas are considered some of his greatest masterpieces; the first, Piano Sonata No. 1 In F Minor, was composed during his conservatory years. His Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 was composed in 1912-13 and, more than any other sonata, encapsulates Scriabin’s philosophical and mystical related influences. Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 is a single movement and lasts about 8-10 minutes. Despite the one movement structure, there are eight large tempo markings throughout the piece that imply a sense of slight division. They are: Moderato Quasi Andante (pg. 1), Molto Meno Vivo (pg. 7), Allegro (pg. 10), Allegro Molto (pg. 13), Alla Marcia (pg. 14), Allegro (p. 15), Presto (pg. 16), and Tempo I (pg. 16). As was common in Scriabin’s later works, the piece is extremely chromatic and atonal. Many of its recurring themes center around the extremely dissonant interval of a minor ninth1, and features several transformations of its opening theme, usually increasing in complexity in each of its restatements. Further, a common Scriabin quality involves his use of 1 Wise, H. Harold, “The relationship of pitch sets to formal structure in the last six piano sonatas of Scriabin," UR Research 1987, p. -

Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations In

MYSTIC CHORD HARMONIC AND LIGHT TRANSFORMATIONS IN ALEXANDER SCRIABIN’S PROMETHEUS by TYLER MATTHEW SECOR A THESIS Presented to the School of Music and Dance and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2013 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Tyler Matthew Secor Title: Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance by: Dr. Jack Boss Chair Dr. Stephen Rodgers Member Dr. Frank Diaz Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2013 ii © 2013 Tyler Matthew Secor iii THESIS ABSTRACT Tyler Matthew Secor Master of Arts School of Music and Dance September 2013 Title: Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus This thesis seeks to explore the voice leading parsimony, bass motion, and chromatic extensions present in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus. Voice leading will be explored using Neo-Riemannian type transformations followed by network diagrams to track the mystic chord movement throughout the symphony. Bass motion and chromatic extensions are explored by expanding the current notion of how the luce voices function in outlining and dictating the harmonic motion. Syneathesia -

Ballet Notes the Seagull March 21 – 25, 2012

Ballet Notes The SeagUll March 21 – 25, 2012 Aleksandar Antonijevic and Sonia Rodriguez as Trigorin and Nina. Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann. Orchestra Violins Trumpets Benjamin Bowman Richard Sandals, Principal Concertmaster Mark Dharmaratnam Lynn KUo, Robert WeymoUth Assistant Concertmaster Trombones DominiqUe Laplante, David Archer, Principal Principal Second Violin Robert FergUson James Aylesworth David Pell, Bass Trombone Jennie Baccante Csaba Ko czó Tuba Sheldon Grabke Sasha Johnson, Principal Xiao Grabke • Nancy Kershaw Harp Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk LUcie Parent, Principal Celia Franca, C.C., FoUnder Yakov Lerner Timpany George Crum, MUsic Director EmeritUs Jayne Maddison Michael Perry, Principal Ron Mah Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Aya Miyagawa Percussion Mark MazUr, Acting Artistic Director ExecUtive Director Wendy Rogers Filip Tomov Principal David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. Joanna Zabrowarna Kristofer Maddigan MUsic Director and Artist-in-Residence PaUl ZevenhUizen Orchestra Personnel Principal CondUctor Violas Manager and Music Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer Angela RUdden, Principal Administrator Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, • Theresa RUdolph Koczó, Jean Verch YOU dance / Ballet Master Assistant Principal Assistant Orchestra Valerie KUinka Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne Personnel Manager Johann Lotter Raymond Tizzard Senior Ballet Master Richardson Beverley Spotton Senior Ballet Mistress • Larry Toman Librarian LUcie Parent Aleksandar Antonijevic, GUillaUme Côté, Cellos Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, Zdenek Konvalina*, -

The Phiiharmonic-Symphony Society 1842 of New York Consolidated 1928

THE PHIIHARMONIC-SYMPHONY SOCIETY 1842 OF NEW YORK CONSOLIDATED 1928 1952 ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH SEASON 1953 Musical Director: DIMITRI MITROPOULOS Guest Conductors: BRUNO WALTER, GEORGE SZELL, GUIDO CANTELLI Associate Conductor: FRANCO AUTORI For Young People’s Concerts: IGOR BUKETOFF CARNEGIE HALL 5176th Concert SUNDAY AFTERNOON, APRIL 19, 1953, at 2:30 Under the Direction of DIMITRI MITROPOULOS Assisting Artist: ARTUR RUBINSTEIN, Pianist FRANCK-PIERNE Prelude, Chorale and Fugue SCRIABIN The Poem of Ecstasy, Opus 54 Intermission SAINT-SAËNS Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 2, G minor, Opus 22 I. Andante sostenuto II. Allegretto scherzando III. Presto Artur Rubinstein FRANCK Symphonic Variations for Piano and Orchestra Artur Rubinstein (Mr. Rubinstein plays the Steinway Piano) ARTHUR JUDSON, BRUNO ZIRATO, Managers THE STEINWAY is the Official Piano of The Philharmonic-Symphony Society COLUMBIA AND VICTOR RECORDS THE PHILHARMONIC-SYMPHONY SOCIETY OF NEW YORK BOARD OF DIRECTORS •Floyd G. Blair........ ........President •Mrs. Lytle Hull... Vice-President •Mrs. John T. Pratt Vice-President ♦Ralph F. Colin Vice-President •Paul G. Pennoyer Vice-President ♦David M. Keiser Treasurer •William Rosenwald Assistant Treasurer •Parker McCollester Secretary •Arthur Judson Executive Secretary Arthur A. Ballantine Arthur A. Houghton, Jr. Mrs. William C. Breed Mrs. Arthur Lehman Chester Burden Mrs. Henry R. Luce •Mrs. Elbridge Gerry Chadwick David H. McAlpin Henry E. Coe Richard E. Myers Pierpont V. Davis William S. Paley Maitland A. Edey •Francis T. P. Plimpton Nevil Ford Mrs. David Rockefeller Mr. J. Peter Grace, Jr. Mrs. George H. Shaw G. Lauder Greenway Spyros P. Skouras •Mrs. Charles S. Guggenheimer •Mrs. Frederick T. Steinway •William R. -

Symphony (In One Movem Ent), Op

ONE MOVEMENT SYMPHONIES BARBER SIBELIUS SCRIABIN MICHAEL STERN KANSAS CITY SYMPH ONY A ‘PROF’ JOHNSON RECORDING SAMUEL BARBER First Symphony (In One Movem ent), Op. 9 (1936) Samuel Barber was born on March 9, 1910 in West Chester, Pennsylvania. His father was a physician and his mother a sister of the famous American contralto, Louise Homer. From the time he was six years old, Barber’s musical gifts were apparent, and at the age of 13 he was accepted as one of the first students to attend the newly established Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. There he studied with Rosario Scalero (composition), Isabelle Vengerova (piano), and Emilio de Gogorza (voice). Although he began composing at the age of seven, he undertook it seriously at 18. Recognition of his gifts as a composer came quickly. In 1933 the Philadelphia Orchestra played his Overture to The School for Scandal and in 1935 the New York Philharmonic presented his Music for a Scene from Shelley . Both early compositions won considerable acclaim. Between 1935 and 1937 Barber was awarded the Prix de Rome and the Pulitzer Prize. He achieved overnight fame on November 5, 1938 when Arturo Toscanini conducted the NBC Symphony Orchestra in Barber’s Essay for Orchestra No. 1 and Adagio for Strings . The Adagio became one of the most popular American works of serious music, and through some lurid aberration of circumstance, it also became a favorite selection at state funerals and as background for death scenes in movies. During World War II, Barber served in the Army Air Corps. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 75, 1955-1956, Trip

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN I88I BY HENRY LEE HI 1955 1956 SEASON Veterans Memorial Auditorium, Providence Boston Symphony Orchestra (Seventy-fifth Season, 1955-1956) CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director RICHARD BURGIN, Associate Conductor PERSONNEL Violins Violas Bassoons Richard Burgin Joseph de Pasquale Sherman Walt Concert-master Jean Cauhape Ernst Panenka Alfred Krips Eugen Lehner Theodore Brewster George Zazofsky Albert Bernard Contra-Bassoon Rolland Tapley George Humphrey Richard Plaster Norbert Lauga Jerome Lipson Robert Karol Vladimir Resnikoff Horns Harry Dickson Reuben Green James Stagliano Gottfried AVilfinger Bernard Kadinoff Charles Yancich Einar Hansen Vincent Mauricci Harry Shapiro Joseph Leibovici John Fiasca Harold Meek Emil Kornsand Violoncellos Paul Keaney Roger Shermont Osbourne McConathy Samuel Mayes Minot Beale Alfred Zighera Herman Silberman Trumpets Jacobus Langendoen Roger Voisin Stanley Benson Mischa Nieland Leo Panasevich Marcel Lafosse Karl Zeise Armando Ghitalla Sheldon Rotenberg Josef Zimbler Gerard Goguen Fredy Ostrovsky Bernard Parronchi Clarence Knudson Leon MarjoUet Trombones Pierre Mayer Martin Hoherman William Gibson Manuel Zung Louis Berger William Moyer Kauko Kabila Samuel Diamond Richard Kapuscinski Josef Orosz Victor Manusevitch Robert Ripley James Nagy Flutes Tuba Melvin Bryant Doriot Anthony Dwyer K. Vinal Smith Lloyd Stonestreet James Pappoutsakis Saverio Messina Phillip Kaplan Harps William Waterhouse Bernard Zighera Piccolo William Marshall Olivia Luetcke Leonard Moss George Madsen Jesse -

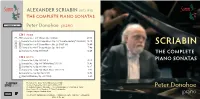

Scriabin (1872-1915) the Complete Piano Sonatas

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN (1872-1915) THE COMPLETE PIANO SONATAS SOMMCD 262-2 Peter Donohoe piano CD 1 [74:34] 1 – 4 Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 6 (1892) 23:58 5 – 6 Sonata No. 2 in G Sharp Minor, Op. 19, “Sonata-Fantasy” (1892-97) 12:10 7 – bl Sonata No. 3 in F Sharp Minor, Op. 23 (1897-98) 18:40 SCRIABIN bm – bn Sonata No. 4 in F Sharp Major, Op. 30 (1903) 7:40 bo Sonata No. 5, Op. 53 (1907) 12:05 THE COMPLETE CD 2 [65:51] 1 Sonata No. 6, Op. 62 (1911) 13:13 PIANO SONATAS 2 Sonata No. 7, Op. 64, “White Mass” (1911) 11:47 3 Sonata No. 8, Op. 66 (1912-13) 13:27 4 Sonata No. 9, Op. 68, “Black Mass” (1912-13) 7:52 5 Sonata No. 10, Op. 70 (1913) 12:59 6 Vers La Flamme, Op. 72 (1914) 6:29 TURNER Recorded live at the Turner Sims Concert Hall SIMS Southampton on 26-28 September 2014 and 2-4 May 2015 Recording Producer: Siva Oke ∙ Recording Engineer: Paul Arden-Taylor Peter Donohoe Front Cover: Peter Donohoe © Chris Cristodoulou Design & Layout: Andrew Giles piano DDD © & 2016 SOMM RECORDINGS · THAMES DITTON · SURREY · ENGLAND Made in the EU SCRIABIN PIANO SONATAS DISC 1 [74:34] SONATA NO. 5, Op. 53 (1907) bo Allegro. Impetuoso. Con stravaganza – Languido – 12:05 SONATA NO. 1 in F Minor, Op. 6 (1892) [23:58] Presto con allegrezza 1 I. Allegro Con Fuoco 9:13 2 II. Crotchet=40 (Lento) 5:01 3 III.