Symphony (In One Movem Ent), Op

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-7-2018 12:30 PM Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse Renee MacKenzie The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nolan, Catherine The University of Western Ontario Sylvestre, Stéphan The University of Western Ontario Kinton, Leslie The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Musical Arts © Renee MacKenzie 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation MacKenzie, Renee, "Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5572. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5572 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This monograph examines the post-exile, multi-version works of Sergei Rachmaninoff with a view to unravelling the sophisticated web of meanings and values attached to them. Compositional revision is an important and complex aspect of creating musical meaning. Considering revision offers an important perspective on the construction and circulation of meanings and discourses attending Rachmaninoff’s music. While Rachmaninoff achieved international recognition during the 1890s as a distinctively Russian musician, I argue that Rachmaninoff’s return to certain compositions through revision played a crucial role in the creation of a narrative and set of tropes representing “Russian diaspora” following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 90, 1970-1971

v^ BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON THURSDAY B 2 FRIDAY -SATURDAY 16 1970-1971 NINETIETH ANNIVERSARY SEASON IP» STRADIVARI created for all time a perfect marriage of precision and beauty for both the eye and the ear. He had the unique genius to combine a thorough knowledge of the acoustical values of wood with a fine artist's sense of the good and the beautiful. Unexcelled by anything before or after, his violins have such purity of tone, they are said to speak with the voice of a lovely soul within. In business, as in the arts, experience and ability are invaluable. We suggest you take advantage of our extensive insurance background by letting us review your needs either business or personal and counsel you to an intelligent program. We respectfully invite your inquiry. CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO., INC Richard P. Nyquist, President Charles G. Carleton, Vice President 147 Milk Street Boston, Massachusetts 02109 542-1250 OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA WILLIAM STEINBERG Music Director MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS Associate Conductor NINETIETH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 1970-1971 THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. TALCOTT M. BANKS President FRANCIS W. HATCH PHILIP K. ALLEN Vice-President HAROLD D. HODGKINSON ROBERT H. GARDINER Vice-President E. MORTON JENNINGS JR JOHN L. THORNDIKE Treasurer EDWARD M. KENNEDY ALLEN G. BARRY HENRY A. LAUGHLIN RICHARD P. CHAPMAN EDWARD G. MURRAY ABRAM T. COLLIER JOHN T. NOONAN MRS HARRIS FAHNESTOCK MRS JAMES H. PERKINS THEODORE P. FERRIS IRVING W. RABB SIDNEY STONEMAN TRUSTEES EMERITUS HENRY B. -

The Phiiharmonic-Symphony Society 1842 of New York Consolidated 1928

THE PHIIHARMONIC-SYMPHONY SOCIETY 1842 OF NEW YORK CONSOLIDATED 1928 1952 ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH SEASON 1953 Musical Director: DIMITRI MITROPOULOS Guest Conductors: BRUNO WALTER, GEORGE SZELL, GUIDO CANTELLI Associate Conductor: FRANCO AUTORI For Young People’s Concerts: IGOR BUKETOFF CARNEGIE HALL 5176th Concert SUNDAY AFTERNOON, APRIL 19, 1953, at 2:30 Under the Direction of DIMITRI MITROPOULOS Assisting Artist: ARTUR RUBINSTEIN, Pianist FRANCK-PIERNE Prelude, Chorale and Fugue SCRIABIN The Poem of Ecstasy, Opus 54 Intermission SAINT-SAËNS Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 2, G minor, Opus 22 I. Andante sostenuto II. Allegretto scherzando III. Presto Artur Rubinstein FRANCK Symphonic Variations for Piano and Orchestra Artur Rubinstein (Mr. Rubinstein plays the Steinway Piano) ARTHUR JUDSON, BRUNO ZIRATO, Managers THE STEINWAY is the Official Piano of The Philharmonic-Symphony Society COLUMBIA AND VICTOR RECORDS THE PHILHARMONIC-SYMPHONY SOCIETY OF NEW YORK BOARD OF DIRECTORS •Floyd G. Blair........ ........President •Mrs. Lytle Hull... Vice-President •Mrs. John T. Pratt Vice-President ♦Ralph F. Colin Vice-President •Paul G. Pennoyer Vice-President ♦David M. Keiser Treasurer •William Rosenwald Assistant Treasurer •Parker McCollester Secretary •Arthur Judson Executive Secretary Arthur A. Ballantine Arthur A. Houghton, Jr. Mrs. William C. Breed Mrs. Arthur Lehman Chester Burden Mrs. Henry R. Luce •Mrs. Elbridge Gerry Chadwick David H. McAlpin Henry E. Coe Richard E. Myers Pierpont V. Davis William S. Paley Maitland A. Edey •Francis T. P. Plimpton Nevil Ford Mrs. David Rockefeller Mr. J. Peter Grace, Jr. Mrs. George H. Shaw G. Lauder Greenway Spyros P. Skouras •Mrs. Charles S. Guggenheimer •Mrs. Frederick T. Steinway •William R. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 75, 1955-1956, Trip

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN I88I BY HENRY LEE HI 1955 1956 SEASON Veterans Memorial Auditorium, Providence Boston Symphony Orchestra (Seventy-fifth Season, 1955-1956) CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director RICHARD BURGIN, Associate Conductor PERSONNEL Violins Violas Bassoons Richard Burgin Joseph de Pasquale Sherman Walt Concert-master Jean Cauhape Ernst Panenka Alfred Krips Eugen Lehner Theodore Brewster George Zazofsky Albert Bernard Contra-Bassoon Rolland Tapley George Humphrey Richard Plaster Norbert Lauga Jerome Lipson Robert Karol Vladimir Resnikoff Horns Harry Dickson Reuben Green James Stagliano Gottfried AVilfinger Bernard Kadinoff Charles Yancich Einar Hansen Vincent Mauricci Harry Shapiro Joseph Leibovici John Fiasca Harold Meek Emil Kornsand Violoncellos Paul Keaney Roger Shermont Osbourne McConathy Samuel Mayes Minot Beale Alfred Zighera Herman Silberman Trumpets Jacobus Langendoen Roger Voisin Stanley Benson Mischa Nieland Leo Panasevich Marcel Lafosse Karl Zeise Armando Ghitalla Sheldon Rotenberg Josef Zimbler Gerard Goguen Fredy Ostrovsky Bernard Parronchi Clarence Knudson Leon MarjoUet Trombones Pierre Mayer Martin Hoherman William Gibson Manuel Zung Louis Berger William Moyer Kauko Kabila Samuel Diamond Richard Kapuscinski Josef Orosz Victor Manusevitch Robert Ripley James Nagy Flutes Tuba Melvin Bryant Doriot Anthony Dwyer K. Vinal Smith Lloyd Stonestreet James Pappoutsakis Saverio Messina Phillip Kaplan Harps William Waterhouse Bernard Zighera Piccolo William Marshall Olivia Luetcke Leonard Moss George Madsen Jesse -

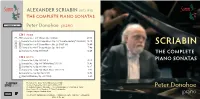

Scriabin (1872-1915) the Complete Piano Sonatas

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN (1872-1915) THE COMPLETE PIANO SONATAS SOMMCD 262-2 Peter Donohoe piano CD 1 [74:34] 1 – 4 Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 6 (1892) 23:58 5 – 6 Sonata No. 2 in G Sharp Minor, Op. 19, “Sonata-Fantasy” (1892-97) 12:10 7 – bl Sonata No. 3 in F Sharp Minor, Op. 23 (1897-98) 18:40 SCRIABIN bm – bn Sonata No. 4 in F Sharp Major, Op. 30 (1903) 7:40 bo Sonata No. 5, Op. 53 (1907) 12:05 THE COMPLETE CD 2 [65:51] 1 Sonata No. 6, Op. 62 (1911) 13:13 PIANO SONATAS 2 Sonata No. 7, Op. 64, “White Mass” (1911) 11:47 3 Sonata No. 8, Op. 66 (1912-13) 13:27 4 Sonata No. 9, Op. 68, “Black Mass” (1912-13) 7:52 5 Sonata No. 10, Op. 70 (1913) 12:59 6 Vers La Flamme, Op. 72 (1914) 6:29 TURNER Recorded live at the Turner Sims Concert Hall SIMS Southampton on 26-28 September 2014 and 2-4 May 2015 Recording Producer: Siva Oke ∙ Recording Engineer: Paul Arden-Taylor Peter Donohoe Front Cover: Peter Donohoe © Chris Cristodoulou Design & Layout: Andrew Giles piano DDD © & 2016 SOMM RECORDINGS · THAMES DITTON · SURREY · ENGLAND Made in the EU SCRIABIN PIANO SONATAS DISC 1 [74:34] SONATA NO. 5, Op. 53 (1907) bo Allegro. Impetuoso. Con stravaganza – Languido – 12:05 SONATA NO. 1 in F Minor, Op. 6 (1892) [23:58] Presto con allegrezza 1 I. Allegro Con Fuoco 9:13 2 II. Crotchet=40 (Lento) 5:01 3 III. -

Alexander Scriabin (1871-1915): Piano Miniature As Chronicle of His

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN (1871-1915): PIANO MINIATURE AS CHRONICLE OF HIS CREATIVE EVOLUTION; COMPLEXITY OF INTERPRETIVE APPROACH AND ITS IMPLICATIONS Nataliya Sukhina, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2008 APPROVED: Vladimir Viardo, Major Professor Elvia Puccinelli, Minor Professor Pamela Paul, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Sukhina, Nataliya. Alexander Scriabin (1871-1915): Piano miniature as chronicle of his creative evolution; Complexity of interpretive approach and its implications. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2008, 86 pp., 30 musical examples, 3 tables, 1 figure, references, 70 titles. Scriabin’s piano miniatures are ideal for the study of evolution of his style, which underwent an extreme transformation. They present heavily concentrated idioms and structural procedures within concise form, therefore making it more accessible to grasp the quintessence of the composer’s thought. A plethora of studies often reviews isolated genres or periods of Scriabin’s legacy, making it impossible to reveal important general tendencies and inner relationships between his pieces. While expanding the boundaries of tonality, Scriabin completed the expansion and universalization of the piano miniature genre. Starting from his middle years the ‘poem’ characteristics can be found in nearly every piece. The key to this process lies in Scriabin’s compilation of certain symbolical musical gestures. Separation between technical means and poetic intention of Scriabin’s works as well as rejection of his metaphysical thought evolution result in serious interpretive implications. -

Prometheus” and the Russian Symbolist Poetics of Light

The Poet of Fire: Aleksandr Skriabin’s Synaesthetic Symphony “Prometheus” and the Russian Symbolist Poetics of Light Polina D. Dimova Summer 2009 Polina D. Dimova is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Comparative Literature at the University of California, Berkeley Jean Delville, Cover Illustration for the Original Score of Aleksandr Skriabin’s “Prometheus: A Poem of Fire” Acknowledgements The writing of this essay on Aleksandr Skriabin and Russian Symbolism would not have been possible without the guidance, thought-provoking discussions, and meticulous readings of my dissertation committee—my advisor, Professor Eric Naiman; Professor Robert P. Hughes; Professor Barbara Spackman; and Professor Richard Taruskin. I was generously funded by a Graduate Division Summer Grant from UC Berkeley for my research trip to Moscow in 2006. I want to express my gratitude to the researchers and staff at The Aleksandr Skriabin State Museum, Moscow, for allowing me to access archival print and video materials, concerning Skriabin’s “Prometheus,” as well as for kindly offering their help and expertise. I have been fortunate to discuss specialized sections of my work with William Quillen, a Berkeley Ph.D. Candidate in Musicology and Donovan Lee, a Berkeley Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. Abstract: This paper discusses the synaesthetically informed metaphors of light, fire, and the Sun in Russian Symbolism and shows their scientific, technological, and cultural resonance in the novel experience of electric light in Russia. The essay studies the harmonic synaesthetics of Aleksandr Skriabin’s symphony “Prometheus, A Poem of Fire”—which also includes an enigmatic musically notated part for an electric organ of lights, along with Symbolist texts concerning light and electricity and the synaesthetic poetry of fire by Skriabin’s close associate Konstantin Bal’mont. -

RUSSIAN Symphonies TCHAIKOVSKY • BORODIN • PROKOFIEV • MYASKOVSKY • SHOSTAKOVICH RIMSKY-KORSAKOV • RACHMANINOV • SCRIABIN • GLAZUNOV • KALINNIKOV

GREAT RUSSIAN SYMPHONIES TCHAIKOVSKY • BORODIN • PROKOFIEV • MYASKOVSKY • SHOSTAKOVICH RIMSKY-KORSAKOV • RACHMANINOV • SCRIABIN • GLAZUNOV • KALINNIKOV 1 8.501059 Rimsky-Korsakov acquired a high degree of musical expertise, helped by leaving the GREAT RUSSIAN SYMPHONIES navy and taking up a position as inspector of naval bands. He remained the most fully professional of the Five, with particular skill in orchestration. In the nature of things TCHAIKOVSKY • BORODIN • PROKOFIEV • MYASKOVSKY Borodin, Mussorgsky and Cui had to combine their careers with composition. Cui, a SHOSTAKOVICH • RIMSKY-KORSAKOV harsh critic, excelled in shorter, genre pieces, while the first two left much unfinished at RACHMANINOV • SCRIABIN • GLAZUNOV • KALINNIKOV their deaths, works to be revised and completed by Rimsky-Korsakov. The Russian composers who followed were able to benefit both from the teaching INTRODUCTION of the Conservatories and from the ideals of the nationalists, but later generations were greatly affected by the course of Russian politics. The first Russian revolution of 1905 had found Rimsky-Korsakov siding with the students in a political disturbance that, for The mid-nineteenth century brought increasing awareness of national identities the time being, lost him his position at the St Petersburg Conservatory. The resulting throughout Europe and not least in Russia. Led by Balakirev, a group of five nationalist constitutional settlement lasted until the final victory of the Bolsheviks in the October Russian composers, described by the polymath Vladimir Stasov as Mogushka, the Revolution of 1917. The establishment of a socialist régime in Russia changed the Mighty Handful, and otherwise known as The Five, worked intermittently together course of Russian music and the lives of Russian musicians. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 51,1931

CARNEGIE HALL .... NEW YORK Friday Evening, February 5, at 8.45 Saturday Afternoon, February 6, at 2.30 PROGR7WVE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA: 188M931" By M. A. De WOLFE HOWE Semi'Centennial Edition It is seventeen years since M. A. De Wolfe Howe's history of the Boston Symphony Orchestra was published. The Fiftieth season of the Orches- tra seemed a fitting time to re-publish this prized narrative of its earlier days, and likewise to record, in additional chapters, the last years of Dr. Muck's conductorship, and the years of Henri Rabaud, Pierre Monteux, and Dr. Serge Koussevitzky. New appendices include a complete list of the music played at the regular concerts, giving the dates of performances. The soloists and the personnel through fifty years are also recorded, and the address on Henry Lee Higginson made by Bliss Perry at the Bach Festival, March 25, 1931. Now on sale at the Box Office, or by money order to Symphony Hall, Boston Price $1.50 (postage included) CARNEGIE HALL - - - NEW YORK Forty-sixth Season in New York FIFTY-FIRST SEASON, 1931-1932 INC. Di SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor FRIDAY EVENING, FEBRUARY 5, at 8.45 AND THE SATURDAY AFTERNOON, FEBRUARY 6, at 2.30 WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE COPYRIGHT, 1932, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. Dr. SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY Fifty-first Season, 1931-1932 Dr. SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor Violins. Burgin, R. Elcus, G. Gundersen, R. Sauvlet, H. Cherkassky, P. Concert-mastei Kassman, N. Hamilton, V. Eisler, D. Theodorowicz, ] Hansen, E. Lauga, N. Fedorovsky, P. Leibovici, J. Pinficld, C. -

The Composer's Approach to the Symphonic Poem

THE COMPOSER'S APPROACH TO THE SYMPHONIC POEM By ALEC PEMBERTON A THESIS Presented to the Department of Music And the Honors College of the University of Oregon In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Bachelor of Science November 2009 11 An Abstract of the Thesis of Alexander Pemberton for the degree of Bachelor of Science in the School of Music 1 November 17 \ 2009 Title: THE COMPOSER'S APPROACH TO THE SYMPHONIC POEM Approved: . The symphonic poem is a term we often apply quite liberally to orchestral works. Because of this, we have grouped together many very different pieces of music, each with extremely unique qualities. If we choose to study any of the many numerous symphonic poems, we find that each composer approaches the work with a specific purpose in mind and accomplishes his task with particular techniques. More importantly, we find that the composer's distinctive approach has significant consequences for the listener. My research compares two symphonic poems to prove these points, Sergei Rachmaninoffs The Isle of the Dead Op.29 and The Poem of Ecstasy Op.54 by Alexander Scriabin. In the first we find that Rachmaninoff creates the symphonic poem and all of its defining features using more traditional techniques. In the second composition, I will argue that Scriabin chooses to abandon convention and instead develops a product unlike any preceding programmatic work. My most 111 profound argument states that one of these approaches fulfils the common goal of a symphonic poem, that is to narrate a clear and complete story, while the other does not. -

Orchestra" Hall (Paradise Theatre) H&BS No

■Orchestra" Hall (Paradise Theatre) H&BS No. - MICH-271 3Tli.;'Woodward Avenue . Detroit WaynS.'-County; ' •Michigan .■/■•'"•■ O'^i PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AMD DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Buildings Survey Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation Department of the Interior Washington, D. C. 2O2U0 5, MICH ,*7-~ \y ^m HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY HABS No. MICH-271 ORCHESTRA EALL (Now Orchestra Hall - Paradise Theatre) Location: 3711 Woodward Avenue, at the northwest corner of Parsons Street, Detroit, Wayne County, Michigan. USGS Detroit Quadrangle, Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: If. 330360.1*690 3^0 Present Owner: The Save Orchestra Hall Committee, Inc., 3711 Wood- ward Avenue, Detroit, Michigan. Present Use: Performing arts and concert hall, now called Orchestra Hall - Paradise Theatre. Restoration is in progress. Statement of Orchestra Hall resembles the typical theatre of its Significance: day, with a restrained and elegant adaptation of Renaissance style that preceded the exhuberant eclecticism of the next decade. It was designed with emphasis on concert requirements, but was fully equipped also for use as a motion-picture theatre. Its appearance and superb acoustics re- 1% flect the ability of C. Howard Crane, a Detroit architect who became one of the most notable national and international architects of the "Movie Palace." Crane's Orchestra Hall, Detroit's first true concert hall, was considered to be one of the finest in the country. Built originally to obtain the services of Ossip Gabrilowitsch as permanent conductor of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, during his tenure the hall was the scene of performances by many renowned artists. Later, as the Paradise Theatre, it offered outstanding concert jazz. -

Season 2015-2016 the Philadelphia Orchestra

Season 2015-2016 The Philadelphia Orchestra Tuesday, May 24, at 7:30 National Centre for the Performing Arts, Beijing, China Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Lang Lang Piano Sibelius Finlandia, Op. 26 Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 1 in F-sharp minor, Op. 1 I. Vivace II. Andante III. Allegro vivace Intermission Rimsky-Korsakov Sheherazade, Op. 35 I. The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship (Largo e maestoso)—Allegro non troppo II. The Tale of the Kalander Prince (Lento— Allegro molto III. The Young Prince and the Young Princess (Andantino quasi allegretto) IV. Festival at Baghdad—The Sea—The Ship Is Wrecked—Conclusion (Allegro molto) The Philadelphia Orchestra The Philadelphia Orchestra is one of the preeminent orchestras in the world, renowned for its distinctive sound, desired for its keen ability to capture the hearts and imaginations of audiences, and admired for a legacy of imagination and innovation on and off the concert stage. The Orchestra is transforming its rich tradition of achievement, sustaining the highest level of artistic quality, but also challenging—and exceeding—that level by creating powerful musical experiences for audiences at home and around the world. Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s highly collaborative style, deeply-rooted musical curiosity, and boundless enthusiasm, paired with a fresh approach to orchestral programming, have been heralded by critics and audiences alike since his inaugural season in 2012. Under his leadership the Orchestra returned to recording, with two celebrated CDs on the prestigious Deutsche Grammophon label, continuing its history of recording success. The Orchestra also reaches thousands of listeners on the radio with weekly Sunday afternoon broadcasts on WRTI-FM.