The Composer's Approach to the Symphonic Poem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Phiiharmonic-Symphony Society 1842 of New York Consolidated 1928

THE PHIIHARMONIC-SYMPHONY SOCIETY 1842 OF NEW YORK CONSOLIDATED 1928 1952 ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH SEASON 1953 Musical Director: DIMITRI MITROPOULOS Guest Conductors: BRUNO WALTER, GEORGE SZELL, GUIDO CANTELLI Associate Conductor: FRANCO AUTORI For Young People’s Concerts: IGOR BUKETOFF CARNEGIE HALL 5176th Concert SUNDAY AFTERNOON, APRIL 19, 1953, at 2:30 Under the Direction of DIMITRI MITROPOULOS Assisting Artist: ARTUR RUBINSTEIN, Pianist FRANCK-PIERNE Prelude, Chorale and Fugue SCRIABIN The Poem of Ecstasy, Opus 54 Intermission SAINT-SAËNS Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 2, G minor, Opus 22 I. Andante sostenuto II. Allegretto scherzando III. Presto Artur Rubinstein FRANCK Symphonic Variations for Piano and Orchestra Artur Rubinstein (Mr. Rubinstein plays the Steinway Piano) ARTHUR JUDSON, BRUNO ZIRATO, Managers THE STEINWAY is the Official Piano of The Philharmonic-Symphony Society COLUMBIA AND VICTOR RECORDS THE PHILHARMONIC-SYMPHONY SOCIETY OF NEW YORK BOARD OF DIRECTORS •Floyd G. Blair........ ........President •Mrs. Lytle Hull... Vice-President •Mrs. John T. Pratt Vice-President ♦Ralph F. Colin Vice-President •Paul G. Pennoyer Vice-President ♦David M. Keiser Treasurer •William Rosenwald Assistant Treasurer •Parker McCollester Secretary •Arthur Judson Executive Secretary Arthur A. Ballantine Arthur A. Houghton, Jr. Mrs. William C. Breed Mrs. Arthur Lehman Chester Burden Mrs. Henry R. Luce •Mrs. Elbridge Gerry Chadwick David H. McAlpin Henry E. Coe Richard E. Myers Pierpont V. Davis William S. Paley Maitland A. Edey •Francis T. P. Plimpton Nevil Ford Mrs. David Rockefeller Mr. J. Peter Grace, Jr. Mrs. George H. Shaw G. Lauder Greenway Spyros P. Skouras •Mrs. Charles S. Guggenheimer •Mrs. Frederick T. Steinway •William R. -

Symphony (In One Movem Ent), Op

ONE MOVEMENT SYMPHONIES BARBER SIBELIUS SCRIABIN MICHAEL STERN KANSAS CITY SYMPH ONY A ‘PROF’ JOHNSON RECORDING SAMUEL BARBER First Symphony (In One Movem ent), Op. 9 (1936) Samuel Barber was born on March 9, 1910 in West Chester, Pennsylvania. His father was a physician and his mother a sister of the famous American contralto, Louise Homer. From the time he was six years old, Barber’s musical gifts were apparent, and at the age of 13 he was accepted as one of the first students to attend the newly established Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. There he studied with Rosario Scalero (composition), Isabelle Vengerova (piano), and Emilio de Gogorza (voice). Although he began composing at the age of seven, he undertook it seriously at 18. Recognition of his gifts as a composer came quickly. In 1933 the Philadelphia Orchestra played his Overture to The School for Scandal and in 1935 the New York Philharmonic presented his Music for a Scene from Shelley . Both early compositions won considerable acclaim. Between 1935 and 1937 Barber was awarded the Prix de Rome and the Pulitzer Prize. He achieved overnight fame on November 5, 1938 when Arturo Toscanini conducted the NBC Symphony Orchestra in Barber’s Essay for Orchestra No. 1 and Adagio for Strings . The Adagio became one of the most popular American works of serious music, and through some lurid aberration of circumstance, it also became a favorite selection at state funerals and as background for death scenes in movies. During World War II, Barber served in the Army Air Corps. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 75, 1955-1956, Trip

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN I88I BY HENRY LEE HI 1955 1956 SEASON Veterans Memorial Auditorium, Providence Boston Symphony Orchestra (Seventy-fifth Season, 1955-1956) CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director RICHARD BURGIN, Associate Conductor PERSONNEL Violins Violas Bassoons Richard Burgin Joseph de Pasquale Sherman Walt Concert-master Jean Cauhape Ernst Panenka Alfred Krips Eugen Lehner Theodore Brewster George Zazofsky Albert Bernard Contra-Bassoon Rolland Tapley George Humphrey Richard Plaster Norbert Lauga Jerome Lipson Robert Karol Vladimir Resnikoff Horns Harry Dickson Reuben Green James Stagliano Gottfried AVilfinger Bernard Kadinoff Charles Yancich Einar Hansen Vincent Mauricci Harry Shapiro Joseph Leibovici John Fiasca Harold Meek Emil Kornsand Violoncellos Paul Keaney Roger Shermont Osbourne McConathy Samuel Mayes Minot Beale Alfred Zighera Herman Silberman Trumpets Jacobus Langendoen Roger Voisin Stanley Benson Mischa Nieland Leo Panasevich Marcel Lafosse Karl Zeise Armando Ghitalla Sheldon Rotenberg Josef Zimbler Gerard Goguen Fredy Ostrovsky Bernard Parronchi Clarence Knudson Leon MarjoUet Trombones Pierre Mayer Martin Hoherman William Gibson Manuel Zung Louis Berger William Moyer Kauko Kabila Samuel Diamond Richard Kapuscinski Josef Orosz Victor Manusevitch Robert Ripley James Nagy Flutes Tuba Melvin Bryant Doriot Anthony Dwyer K. Vinal Smith Lloyd Stonestreet James Pappoutsakis Saverio Messina Phillip Kaplan Harps William Waterhouse Bernard Zighera Piccolo William Marshall Olivia Luetcke Leonard Moss George Madsen Jesse -

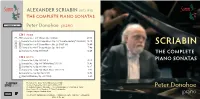

Scriabin (1872-1915) the Complete Piano Sonatas

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN (1872-1915) THE COMPLETE PIANO SONATAS SOMMCD 262-2 Peter Donohoe piano CD 1 [74:34] 1 – 4 Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 6 (1892) 23:58 5 – 6 Sonata No. 2 in G Sharp Minor, Op. 19, “Sonata-Fantasy” (1892-97) 12:10 7 – bl Sonata No. 3 in F Sharp Minor, Op. 23 (1897-98) 18:40 SCRIABIN bm – bn Sonata No. 4 in F Sharp Major, Op. 30 (1903) 7:40 bo Sonata No. 5, Op. 53 (1907) 12:05 THE COMPLETE CD 2 [65:51] 1 Sonata No. 6, Op. 62 (1911) 13:13 PIANO SONATAS 2 Sonata No. 7, Op. 64, “White Mass” (1911) 11:47 3 Sonata No. 8, Op. 66 (1912-13) 13:27 4 Sonata No. 9, Op. 68, “Black Mass” (1912-13) 7:52 5 Sonata No. 10, Op. 70 (1913) 12:59 6 Vers La Flamme, Op. 72 (1914) 6:29 TURNER Recorded live at the Turner Sims Concert Hall SIMS Southampton on 26-28 September 2014 and 2-4 May 2015 Recording Producer: Siva Oke ∙ Recording Engineer: Paul Arden-Taylor Peter Donohoe Front Cover: Peter Donohoe © Chris Cristodoulou Design & Layout: Andrew Giles piano DDD © & 2016 SOMM RECORDINGS · THAMES DITTON · SURREY · ENGLAND Made in the EU SCRIABIN PIANO SONATAS DISC 1 [74:34] SONATA NO. 5, Op. 53 (1907) bo Allegro. Impetuoso. Con stravaganza – Languido – 12:05 SONATA NO. 1 in F Minor, Op. 6 (1892) [23:58] Presto con allegrezza 1 I. Allegro Con Fuoco 9:13 2 II. Crotchet=40 (Lento) 5:01 3 III. -

Alexander Scriabin (1871-1915): Piano Miniature As Chronicle of His

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN (1871-1915): PIANO MINIATURE AS CHRONICLE OF HIS CREATIVE EVOLUTION; COMPLEXITY OF INTERPRETIVE APPROACH AND ITS IMPLICATIONS Nataliya Sukhina, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2008 APPROVED: Vladimir Viardo, Major Professor Elvia Puccinelli, Minor Professor Pamela Paul, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Sukhina, Nataliya. Alexander Scriabin (1871-1915): Piano miniature as chronicle of his creative evolution; Complexity of interpretive approach and its implications. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2008, 86 pp., 30 musical examples, 3 tables, 1 figure, references, 70 titles. Scriabin’s piano miniatures are ideal for the study of evolution of his style, which underwent an extreme transformation. They present heavily concentrated idioms and structural procedures within concise form, therefore making it more accessible to grasp the quintessence of the composer’s thought. A plethora of studies often reviews isolated genres or periods of Scriabin’s legacy, making it impossible to reveal important general tendencies and inner relationships between his pieces. While expanding the boundaries of tonality, Scriabin completed the expansion and universalization of the piano miniature genre. Starting from his middle years the ‘poem’ characteristics can be found in nearly every piece. The key to this process lies in Scriabin’s compilation of certain symbolical musical gestures. Separation between technical means and poetic intention of Scriabin’s works as well as rejection of his metaphysical thought evolution result in serious interpretive implications. -

Prometheus” and the Russian Symbolist Poetics of Light

The Poet of Fire: Aleksandr Skriabin’s Synaesthetic Symphony “Prometheus” and the Russian Symbolist Poetics of Light Polina D. Dimova Summer 2009 Polina D. Dimova is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Comparative Literature at the University of California, Berkeley Jean Delville, Cover Illustration for the Original Score of Aleksandr Skriabin’s “Prometheus: A Poem of Fire” Acknowledgements The writing of this essay on Aleksandr Skriabin and Russian Symbolism would not have been possible without the guidance, thought-provoking discussions, and meticulous readings of my dissertation committee—my advisor, Professor Eric Naiman; Professor Robert P. Hughes; Professor Barbara Spackman; and Professor Richard Taruskin. I was generously funded by a Graduate Division Summer Grant from UC Berkeley for my research trip to Moscow in 2006. I want to express my gratitude to the researchers and staff at The Aleksandr Skriabin State Museum, Moscow, for allowing me to access archival print and video materials, concerning Skriabin’s “Prometheus,” as well as for kindly offering their help and expertise. I have been fortunate to discuss specialized sections of my work with William Quillen, a Berkeley Ph.D. Candidate in Musicology and Donovan Lee, a Berkeley Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. Abstract: This paper discusses the synaesthetically informed metaphors of light, fire, and the Sun in Russian Symbolism and shows their scientific, technological, and cultural resonance in the novel experience of electric light in Russia. The essay studies the harmonic synaesthetics of Aleksandr Skriabin’s symphony “Prometheus, A Poem of Fire”—which also includes an enigmatic musically notated part for an electric organ of lights, along with Symbolist texts concerning light and electricity and the synaesthetic poetry of fire by Skriabin’s close associate Konstantin Bal’mont. -

RUSSIAN Symphonies TCHAIKOVSKY • BORODIN • PROKOFIEV • MYASKOVSKY • SHOSTAKOVICH RIMSKY-KORSAKOV • RACHMANINOV • SCRIABIN • GLAZUNOV • KALINNIKOV

GREAT RUSSIAN SYMPHONIES TCHAIKOVSKY • BORODIN • PROKOFIEV • MYASKOVSKY • SHOSTAKOVICH RIMSKY-KORSAKOV • RACHMANINOV • SCRIABIN • GLAZUNOV • KALINNIKOV 1 8.501059 Rimsky-Korsakov acquired a high degree of musical expertise, helped by leaving the GREAT RUSSIAN SYMPHONIES navy and taking up a position as inspector of naval bands. He remained the most fully professional of the Five, with particular skill in orchestration. In the nature of things TCHAIKOVSKY • BORODIN • PROKOFIEV • MYASKOVSKY Borodin, Mussorgsky and Cui had to combine their careers with composition. Cui, a SHOSTAKOVICH • RIMSKY-KORSAKOV harsh critic, excelled in shorter, genre pieces, while the first two left much unfinished at RACHMANINOV • SCRIABIN • GLAZUNOV • KALINNIKOV their deaths, works to be revised and completed by Rimsky-Korsakov. The Russian composers who followed were able to benefit both from the teaching INTRODUCTION of the Conservatories and from the ideals of the nationalists, but later generations were greatly affected by the course of Russian politics. The first Russian revolution of 1905 had found Rimsky-Korsakov siding with the students in a political disturbance that, for The mid-nineteenth century brought increasing awareness of national identities the time being, lost him his position at the St Petersburg Conservatory. The resulting throughout Europe and not least in Russia. Led by Balakirev, a group of five nationalist constitutional settlement lasted until the final victory of the Bolsheviks in the October Russian composers, described by the polymath Vladimir Stasov as Mogushka, the Revolution of 1917. The establishment of a socialist régime in Russia changed the Mighty Handful, and otherwise known as The Five, worked intermittently together course of Russian music and the lives of Russian musicians. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 53,1933-1934, Trip

ACADEMY OF MUSIC . BROOKLYN Friday Evening, March 2, at 8.15 Under the auspices of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences and the Philharmonio Society of Brooklyn V} m I 3T '£ BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. FIFTY-THIRD SEASON 1933-1934 Bostoe Symphony Orchestra Fifty-third Season, 1933-1934 Dr. SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY. Conductor Violins. Burgin, R. Elcus, G. Lauga, N. Sauvlet, H. Resnikoff, V. Concert-master Gundersen, R. Kassman, N. Cherkassky, P. Eisler, D. Theodorowicz, J. Tapley, R. Mariotti, V. Fedorovsky, P. Knudson, C. Leibovici, J. Pinfield, C. Leveen, P. Hansen, E. Zung, M. Del Sordo, R. Gorodetzky, L Mayer, P. Diamond, S. Bryant, M. Fiedler, B. Zide, L. Beale, M. Stonestreet, L. Messina, S. Murray, J. Erkelens, H. Seiniger, S. Violas. Lefranc, J. Fourel, G. Bernard, A. Grover, H. Artieres, L. Cauhape, J. Van Wynbergen C. Werner, H. Avierino, N. Deane, C. Gerhardt, S. Jacob, R. Violoncellos. Bedetti, J. Langendoen, Chardon, Y. Stockbridge, C. Fabrizio, E. Zighera, A. Barth, C. Droeghmans, H. Warnke, J. Marjollet, L Basses. Kunze, M. Lemaire, J. Ludwig, O. Girard, H. Vondrak, A. Moleux, G. Frankel, I. Dufresne, G. Flutes. Oboes. Clarinets. Bassoons. Laurent, G. Gillet, F. Polatschek, V. Laus, A. Bladet, G. Devergie, J. Valerio, M. Allard, R. Amerena, P. Stanislaus, H. Mazzeo, R. Panenka, E. Arcieri, E. Piccolo. English Horn. Bass Clarinet. Contra-Bassoon Battles, A. Speyer, L. Mimart, P. Piller, B. Horns. Horns. Trumpets. Trombones. Boettcher, G. Valkenier, W. Mager, G. Raichman, J. Macdonald, W. Lannoye, M. Lafosse, M. Hansotte, L. Valkenier, W. Singer, J. Grundey, T. Kenfield, L. Lorbe:r, H. -

Scriabin: Towards the Flame Professor Marina Frolova-Walker 20 May 2021 the Philosophy Those Who Know Scriabin's Music Well Pu

Scriabin: Towards the Flame Professor Marina Frolova-Walker 20 May 2021 The Philosophy Those who know Scriabin’s music well puzzle over his lack of wider recognition, especially in the West. One of the obstacles is to be found in Scriabin’s mystical thinking, which seems impenetrable, irrational, or even repugnant, and yet Scriabin insisted that his music was simply the artistic expression of this mysticism and the two could not be separated. Let us confront this obstacle first. Scriabin was not a scholar. His library was small, and he was easily influenced by acquaintances who would pull him in different directions, towards Theosophy, Hinduism, yoga or various other systems of thought that the composer found attractively exotic. This strange brew of ideas never coalesced into anything that could be called a philosophical system, and he merely drew on ideas that were popular in artistic circles at the time without trying to reconcile them. This was a period in Russia when revolutionary ideas were mixed with apocalyptic presentiments, and when a crisis of institutionalised religion led to the mushrooming of mysticism, and explorations of Buddhism and Hinduism fuelled the search for a universal religion. One strain was even called “God–building”. The Symbolist movement that encompassed all the arts drew from the notion that the visible, material world contains only the symbols of a more real world beyond. The chart shows the main sources of Scriabin’s mystical ideas and their disparate nature. The Piano Sonatas Scriabin’s ten piano sonatas span his entire artistic career, although the last five are clustered towards the end, in the period from 1911 to 1913. -

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2018-2019 Mellon Grand Classics Season

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2018-2019 Mellon Grand Classics Season January 11, 12 and 13, 2019 MARKUS STENZ, CONDUCTOR BEHZOD ABDURAIMOV, PIANO CLAUDE DEBUSSY La cathédrale engloutie (arr. Matthews) SERGEI RACHMANINOFF Concerto No. 2 in C minor for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 18 I. Moderato II. Adagio sostenuto III. Allegro scherzando Mr. Abduraimov Intermission FERRUCCIO BUSONI Berceuse élégiaque, Poem for Orchestra, Opus 42 ALEXANDER SCRIABIN The Poem of Ecstasy (Symphony No. 4), Opus 54 Jan. 11-13, 2019, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA CLAUDE DEBUSSY La cathédrale engloutie, Arranged for Orchestra by Colin Matthews Claude Debussy was born in St. Germain-en-Laye (near Paris) on August 2, 1862, and died in Paris on March 25, 1918. He composed La cathédrale engloutie (“The Sunken Cathedral”) in 1910, which is part of the first book of his Préludes for Piano, and it was premiered by Debussy at the Société Musicale Indépendente in Paris on May 25, 1910. The arrangement heard this weekend was premiered in Manchester by the Hallé Orchestra with conductor Sir Mark Elder on May 6, 2007. These performances mark the Pittsburgh Symphony premiere of the work. The score calls for two piccolos, two flutes, alto flute, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, bass clarinet, contra bass clarinet, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, two harps, celesta and strings. Performance time: approximately 6 minutes. “The sound of the sea, the curve of the horizon, the wind in the leaves, the cry of a bird enregister complex impressions within us,” Debussy told an interviewer when he was at work on his Préludes. -

Programnotes Tchaikovsky Sy

PROGRAM ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FOURTH SEASON Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, February 26, 2015, at 8:00 Friday, February 27, 2015, at 1:30 Saturday, February 28, 2015, at 8:00 Tuesday, March 3, 2015, at 7:30 Riccardo Muti Conductor Scriabin Symphony No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 29 Andante Allegro Andante Tempestoso Maestoso INTERMISSION Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 6 in B Minor, Op. 74 (Pathétique) Adagio—Allegro non troppo Allegro con grazia Allegro molto vivace Finale: Adagio lamentoso This concert series is made possible by the Juli Grainger Endowment. CSO Tuesday series concerts are sponsored by United Airlines. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. COMMENTS by Phillip Huscher Alexander Scriabin Born January 6, 1872 [December 25, 1871, old style], Moscow, Russia. Died April 27, 1915, Moscow, Russia. Symphony No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 29 From his youth, when he etudes, and even Polish mazurkas. To study the interpreted the signifi- first nineteen opus numbers in Scriabin’s catalog, cance of his birth on all pieces for piano solo, one would never pre- Christmas Day as a sign dict the important orchestral music that would that he should do great quickly follow. things, Scriabin believed he would play a decisive he move away from writing solo piano role in the history of music was a tough and decisive step for all music. -

Alexander Scriabin: Aesthetic Development Through Selected Piano Works by Nuno Cernadas

Alexander Scriabin: Aesthetic Development through Selected Piano Works By Nuno Cernadas Master Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music Hochschule für Musik Freiburg March 2013 2 I give full flowering to each feeling, each search, each thirst. I raise you up, legions of feelings, pure activity, my children. I raise you, my complicated, unified feelings, and embrace all of you as my one activity, my one ecstasy, bliss, my last moment. I am God. I raise you up, and I am resurrected, and then I kiss you and lacerate you. I am spent and weary, and then I take you. In this divine act I know you to be one with me. I give you to know this bliss, too. You will be resurrected in me, the more I am incomprehensible to you. I will ignite your imagination with the delight of my promise. I will bedeck you in the excellence of my dreams. I will veil the sky of your wishes with the sparkling stars of my creation. I bring not truth, but freedom.1 Alexander Scriabin 1 Scriabin’s Notebooks, quoted in: Bowers, Faubion. The New Scriabin: Enigma and Answers. Newton Abbot London: David & Charles, 1974, p.115-116. 3 4 5 Acknowledgements I would like to express my profound gratitude to the Coordinator of the present Thesis, Prof. Dr. Ludwig Holtmeier, for all his support and scientific advice. I would also like to convey my appreciation to Prof. Hans Fuhlbom and Prof. Gilead Mishory of the Hochschule für Musik Freiburg, and to Prof.