Gawboy and Townsend, Scriabin and the Possible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 © Copyright by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age by Ryan Isao Rowen Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Mitchell Bryan Morris, Chair The Silver Age has long been considered one of the most vibrant artistic movements in Russian history. Due to sweeping changes that were occurring across Russia, culminating in the 1917 Revolution, the apocalyptic sentiments of the general populace caused many intellectuals and artists to turn towards esotericism and occult thought. With this, there was an increased interest in transcendentalism, and art was becoming much more abstract. The tenets of the Russian Symbolist movement epitomized this trend. Poets and philosophers, such as Vladimir Solovyov, Andrei Bely, and Vyacheslav Ivanov, theorized about the spiritual aspects of words and music. It was music, however, that was singled out as possessing transcendental properties. In recent decades, there has been a surge in scholarly work devoted to the transcendent strain in Russian Symbolism. The end of the Cold War has brought renewed interest in trying to understand such an enigmatic period in Russian culture. While much scholarship has been ii devoted to Symbolist poetry, there has been surprisingly very little work devoted to understanding how the soundscape of music works within the sphere of Symbolism. -

Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin

Analysis of Scriabin’s Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) was a Russian composer and pianist. An early modern composer, Scriabin’s inventiveness and controversial techniques, inspired by mysticism, synesthesia, and theology, contributed greatly to redefining Russian piano music and the modern musical era as a whole. Scriabin studied at the Moscow Conservatory with peers Anton Arensky, Sergei Taneyev, and Vasily Safonov. His ten piano sonatas are considered some of his greatest masterpieces; the first, Piano Sonata No. 1 In F Minor, was composed during his conservatory years. His Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 was composed in 1912-13 and, more than any other sonata, encapsulates Scriabin’s philosophical and mystical related influences. Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 is a single movement and lasts about 8-10 minutes. Despite the one movement structure, there are eight large tempo markings throughout the piece that imply a sense of slight division. They are: Moderato Quasi Andante (pg. 1), Molto Meno Vivo (pg. 7), Allegro (pg. 10), Allegro Molto (pg. 13), Alla Marcia (pg. 14), Allegro (p. 15), Presto (pg. 16), and Tempo I (pg. 16). As was common in Scriabin’s later works, the piece is extremely chromatic and atonal. Many of its recurring themes center around the extremely dissonant interval of a minor ninth1, and features several transformations of its opening theme, usually increasing in complexity in each of its restatements. Further, a common Scriabin quality involves his use of 1 Wise, H. Harold, “The relationship of pitch sets to formal structure in the last six piano sonatas of Scriabin," UR Research 1987, p. -

Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations In

MYSTIC CHORD HARMONIC AND LIGHT TRANSFORMATIONS IN ALEXANDER SCRIABIN’S PROMETHEUS by TYLER MATTHEW SECOR A THESIS Presented to the School of Music and Dance and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2013 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Tyler Matthew Secor Title: Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance by: Dr. Jack Boss Chair Dr. Stephen Rodgers Member Dr. Frank Diaz Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2013 ii © 2013 Tyler Matthew Secor iii THESIS ABSTRACT Tyler Matthew Secor Master of Arts School of Music and Dance September 2013 Title: Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus This thesis seeks to explore the voice leading parsimony, bass motion, and chromatic extensions present in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus. Voice leading will be explored using Neo-Riemannian type transformations followed by network diagrams to track the mystic chord movement throughout the symphony. Bass motion and chromatic extensions are explored by expanding the current notion of how the luce voices function in outlining and dictating the harmonic motion. Syneathesia -

Ballet Notes the Seagull March 21 – 25, 2012

Ballet Notes The SeagUll March 21 – 25, 2012 Aleksandar Antonijevic and Sonia Rodriguez as Trigorin and Nina. Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann. Orchestra Violins Trumpets Benjamin Bowman Richard Sandals, Principal Concertmaster Mark Dharmaratnam Lynn KUo, Robert WeymoUth Assistant Concertmaster Trombones DominiqUe Laplante, David Archer, Principal Principal Second Violin Robert FergUson James Aylesworth David Pell, Bass Trombone Jennie Baccante Csaba Ko czó Tuba Sheldon Grabke Sasha Johnson, Principal Xiao Grabke • Nancy Kershaw Harp Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk LUcie Parent, Principal Celia Franca, C.C., FoUnder Yakov Lerner Timpany George Crum, MUsic Director EmeritUs Jayne Maddison Michael Perry, Principal Ron Mah Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Aya Miyagawa Percussion Mark MazUr, Acting Artistic Director ExecUtive Director Wendy Rogers Filip Tomov Principal David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. Joanna Zabrowarna Kristofer Maddigan MUsic Director and Artist-in-Residence PaUl ZevenhUizen Orchestra Personnel Principal CondUctor Violas Manager and Music Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer Angela RUdden, Principal Administrator Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, • Theresa RUdolph Koczó, Jean Verch YOU dance / Ballet Master Assistant Principal Assistant Orchestra Valerie KUinka Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne Personnel Manager Johann Lotter Raymond Tizzard Senior Ballet Master Richardson Beverley Spotton Senior Ballet Mistress • Larry Toman Librarian LUcie Parent Aleksandar Antonijevic, GUillaUme Côté, Cellos Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, Zdenek Konvalina*, -

MARC-ANDRÉ HAMELIN Plays the Composer-Pianists Alkan

MARC-ANDRÉ HAMELIN plays The Composer-Pianists Alkan . Busoni Feinberg . Godowsky Hamelin . Medtner Rachmaninov Scriabin Sorabji HE RELATION between musical effect and the technical ‘encore’ repertoire; less convincingly as regards the latter half means necessary for its creation or recreation is apt to of a recital, which at one time might have been entirely Tbe one of opposites. The ‘Representation of Chaos’ with devoted to the type of confection indicated above. However, it which Haydn embarked on The Creation, for example, could can be said that the present offers the best of all liberal worlds, not have succeeded without a conspicuously well ordered in which deeply serious artists may leaven but not demean the compositional technique, nor could the percussion- and intellectual and spiritual weight of their mainstream reper- timpani-based anarchy of Nielsen’s Fourth and Fifth toire by restoring to public attention the full variety and zest of Symphonies or, indeed, the ‘controlled chance’ of more a once discredited milieu. In this connection the abstract recent, aleatory trends. A true chaos of means leads only to nature and importance of ‘pianism’ itself should be empha- incoherence, whereas an intended one of expressive ends may sized: for the serious performing artist the purely physical, be likened to the birth of a universe: explosive, precipitate, callisthenic dimension in Tausig, Rosenthal, Schulz-Evler, seemingly beyond all elemental control, and yet achieved with Scharwenka, Hoffman, Godowsky and others illumines the the pinprick accuracy of some infinitely magnified snowflake, nature of the instrument, and of the art itself, in myriad and defying our later scrutiny to find in it mere accident rather idiosyncratic ways. -

The Phiiharmonic-Symphony Society 1842 of New York Consolidated 1928

THE PHIIHARMONIC-SYMPHONY SOCIETY 1842 OF NEW YORK CONSOLIDATED 1928 1952 ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH SEASON 1953 Musical Director: DIMITRI MITROPOULOS Guest Conductors: BRUNO WALTER, GEORGE SZELL, GUIDO CANTELLI Associate Conductor: FRANCO AUTORI For Young People’s Concerts: IGOR BUKETOFF CARNEGIE HALL 5176th Concert SUNDAY AFTERNOON, APRIL 19, 1953, at 2:30 Under the Direction of DIMITRI MITROPOULOS Assisting Artist: ARTUR RUBINSTEIN, Pianist FRANCK-PIERNE Prelude, Chorale and Fugue SCRIABIN The Poem of Ecstasy, Opus 54 Intermission SAINT-SAËNS Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 2, G minor, Opus 22 I. Andante sostenuto II. Allegretto scherzando III. Presto Artur Rubinstein FRANCK Symphonic Variations for Piano and Orchestra Artur Rubinstein (Mr. Rubinstein plays the Steinway Piano) ARTHUR JUDSON, BRUNO ZIRATO, Managers THE STEINWAY is the Official Piano of The Philharmonic-Symphony Society COLUMBIA AND VICTOR RECORDS THE PHILHARMONIC-SYMPHONY SOCIETY OF NEW YORK BOARD OF DIRECTORS •Floyd G. Blair........ ........President •Mrs. Lytle Hull... Vice-President •Mrs. John T. Pratt Vice-President ♦Ralph F. Colin Vice-President •Paul G. Pennoyer Vice-President ♦David M. Keiser Treasurer •William Rosenwald Assistant Treasurer •Parker McCollester Secretary •Arthur Judson Executive Secretary Arthur A. Ballantine Arthur A. Houghton, Jr. Mrs. William C. Breed Mrs. Arthur Lehman Chester Burden Mrs. Henry R. Luce •Mrs. Elbridge Gerry Chadwick David H. McAlpin Henry E. Coe Richard E. Myers Pierpont V. Davis William S. Paley Maitland A. Edey •Francis T. P. Plimpton Nevil Ford Mrs. David Rockefeller Mr. J. Peter Grace, Jr. Mrs. George H. Shaw G. Lauder Greenway Spyros P. Skouras •Mrs. Charles S. Guggenheimer •Mrs. Frederick T. Steinway •William R. -

Symphony (In One Movem Ent), Op

ONE MOVEMENT SYMPHONIES BARBER SIBELIUS SCRIABIN MICHAEL STERN KANSAS CITY SYMPH ONY A ‘PROF’ JOHNSON RECORDING SAMUEL BARBER First Symphony (In One Movem ent), Op. 9 (1936) Samuel Barber was born on March 9, 1910 in West Chester, Pennsylvania. His father was a physician and his mother a sister of the famous American contralto, Louise Homer. From the time he was six years old, Barber’s musical gifts were apparent, and at the age of 13 he was accepted as one of the first students to attend the newly established Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. There he studied with Rosario Scalero (composition), Isabelle Vengerova (piano), and Emilio de Gogorza (voice). Although he began composing at the age of seven, he undertook it seriously at 18. Recognition of his gifts as a composer came quickly. In 1933 the Philadelphia Orchestra played his Overture to The School for Scandal and in 1935 the New York Philharmonic presented his Music for a Scene from Shelley . Both early compositions won considerable acclaim. Between 1935 and 1937 Barber was awarded the Prix de Rome and the Pulitzer Prize. He achieved overnight fame on November 5, 1938 when Arturo Toscanini conducted the NBC Symphony Orchestra in Barber’s Essay for Orchestra No. 1 and Adagio for Strings . The Adagio became one of the most popular American works of serious music, and through some lurid aberration of circumstance, it also became a favorite selection at state funerals and as background for death scenes in movies. During World War II, Barber served in the Army Air Corps. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 75, 1955-1956, Trip

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN I88I BY HENRY LEE HI 1955 1956 SEASON Veterans Memorial Auditorium, Providence Boston Symphony Orchestra (Seventy-fifth Season, 1955-1956) CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director RICHARD BURGIN, Associate Conductor PERSONNEL Violins Violas Bassoons Richard Burgin Joseph de Pasquale Sherman Walt Concert-master Jean Cauhape Ernst Panenka Alfred Krips Eugen Lehner Theodore Brewster George Zazofsky Albert Bernard Contra-Bassoon Rolland Tapley George Humphrey Richard Plaster Norbert Lauga Jerome Lipson Robert Karol Vladimir Resnikoff Horns Harry Dickson Reuben Green James Stagliano Gottfried AVilfinger Bernard Kadinoff Charles Yancich Einar Hansen Vincent Mauricci Harry Shapiro Joseph Leibovici John Fiasca Harold Meek Emil Kornsand Violoncellos Paul Keaney Roger Shermont Osbourne McConathy Samuel Mayes Minot Beale Alfred Zighera Herman Silberman Trumpets Jacobus Langendoen Roger Voisin Stanley Benson Mischa Nieland Leo Panasevich Marcel Lafosse Karl Zeise Armando Ghitalla Sheldon Rotenberg Josef Zimbler Gerard Goguen Fredy Ostrovsky Bernard Parronchi Clarence Knudson Leon MarjoUet Trombones Pierre Mayer Martin Hoherman William Gibson Manuel Zung Louis Berger William Moyer Kauko Kabila Samuel Diamond Richard Kapuscinski Josef Orosz Victor Manusevitch Robert Ripley James Nagy Flutes Tuba Melvin Bryant Doriot Anthony Dwyer K. Vinal Smith Lloyd Stonestreet James Pappoutsakis Saverio Messina Phillip Kaplan Harps William Waterhouse Bernard Zighera Piccolo William Marshall Olivia Luetcke Leonard Moss George Madsen Jesse -

Mengjiao Yan Phd Thesis.Pdf

The University of Sheffield Stravinsky’s piano works from three distinct periods: aspects of performance and latitude of interpretation Mengjiao Yan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music The University of Sheffield Jessop Building, Sheffield, S3 7RD, UK September 2019 1 Abstract This research project focuses on the piano works of Igor Stravinsky. This performance- orientated approach and analysis aims to offer useful insights into how to interpret and make informed decisions regarding his piano music. The focus is on three piano works: Piano Sonata in F-Sharp Minor (1904), Serenade in A (1925), Movements for Piano and Orchestra (1958–59). It identifies the key factors which influenced his works and his compositional process. The aims are to provide an informed approach to his piano works, which are generally considered difficult and challenging pieces to perform convincingly. In this way, it is possible to offer insights which could help performers fully understand his works and apply this knowledge to performance. The study also explores aspects of latitude in interpreting his works and how to approach the notated scores. The methods used in the study include document analysis, analysis of music score, recording and interview data. The interview participants were carefully selected professional pianists who are considered experts in their field and, therefore, authorities on Stravinsky's piano works. The findings of the results reveal the complex and multi-faceted nature of Stravinsky’s piano music. The research highlights both the intrinsic differences in the stylistic features of the three pieces, as well as similarities and differences regarding Stravinsky’s compositional approach. -

Summary of Dissertation Recitals by Zixiang Wang

Summary of Dissertation Recitals by Zixiang Wang A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Arthur Greene, Chair Professor James Borders Lecturer Amy I-Lin Cheng Professor Logan Skelton Associate Professor Gregory Wakefield Zixiang Wang [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2601-5804 © Zixiang Wang 2020 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of my grandmother. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my teacher, Professor Arthur Greene, for his tremendous support and excellent guidance in this journey. I also want to thank my dissertation committee for their generous help and encouragement. Finally, I want to thank my parents for their selfless love. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii LIST OF EXAMPLES v ABSTRACT vi RECITAL 1 1 Recital 1 Program 1 Recital 1 Program Notes 2 RECITAL 2 5 Recital 2 Program 5 Recital 2 Program Notes 6 RECITAL 3 9 Recital 3 Program 9 Recital 3 Lecture Script 10 Biography 21 iv LIST OF EXAMPLES EXAMPLE 1.a Scriabin Sonata No. 1 1st movement, m. 1 Three-Note-Scale Motif 14 1.b Scriabin Sonata No. 1 4th movement, mm. 1-2 Funeral March Motif 14 2 Scriabin Sonata No. 1 1st movement, mm. 1-2 15 3.a Chopin Scherzo No. 2 in B-flat Minor, Op. 31, mm. 1-9 17 3.b Scriabin Sonata No. 1, 3rd movement, m. 13 17 4 Scriabin Sonata No. 1, 3rd movement, mm. 77-86 18 5 Scriabin Sonata No. -

The Performing Style of Alexander Scriabin

Performance Practice Review Volume 18 | Number 1 Article 4 "The eP rforming Style of Alexander Scriabin" by Anatole Leikin Lincoln M. Ballard Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Ballard, Lincoln M. (2013) ""The eP rforming Style of Alexander Scriabin" by Anatole Leikin," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 18: No. 1, Article 4. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.201318.01.04 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol18/iss1/4 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book review: Leikin, Anatole. The Performing Style of Alexander Scriabin. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2011. ISBN 978-0-7546-6021-7. Lincoln M. Ballard Nearly a century after the death of Russian pianist-composer Alexander Scriabin (1872–1915), his music remains as enigmatic as it was during his lifetime. His output is dominated by solo piano music that surpasses most amateurs’ capabilities, yet even among concert artists his works languish on the fringes of the standard repertory. Since the 1980s, Scriabin has enjoyed renewed attention from scholars who have contributed two types of studies aside from examinations of his cultural context: theoretical analyses and performance guides. The former group considers Scriabin as an innovative harmoni- cist who paralleled the Second Viennese School’s development of post-tonal procedures, while the latter elucidates the interpretive and technical demands required to deliver compelling performances of his music. -

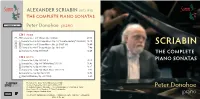

Scriabin (1872-1915) the Complete Piano Sonatas

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN (1872-1915) THE COMPLETE PIANO SONATAS SOMMCD 262-2 Peter Donohoe piano CD 1 [74:34] 1 – 4 Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 6 (1892) 23:58 5 – 6 Sonata No. 2 in G Sharp Minor, Op. 19, “Sonata-Fantasy” (1892-97) 12:10 7 – bl Sonata No. 3 in F Sharp Minor, Op. 23 (1897-98) 18:40 SCRIABIN bm – bn Sonata No. 4 in F Sharp Major, Op. 30 (1903) 7:40 bo Sonata No. 5, Op. 53 (1907) 12:05 THE COMPLETE CD 2 [65:51] 1 Sonata No. 6, Op. 62 (1911) 13:13 PIANO SONATAS 2 Sonata No. 7, Op. 64, “White Mass” (1911) 11:47 3 Sonata No. 8, Op. 66 (1912-13) 13:27 4 Sonata No. 9, Op. 68, “Black Mass” (1912-13) 7:52 5 Sonata No. 10, Op. 70 (1913) 12:59 6 Vers La Flamme, Op. 72 (1914) 6:29 TURNER Recorded live at the Turner Sims Concert Hall SIMS Southampton on 26-28 September 2014 and 2-4 May 2015 Recording Producer: Siva Oke ∙ Recording Engineer: Paul Arden-Taylor Peter Donohoe Front Cover: Peter Donohoe © Chris Cristodoulou Design & Layout: Andrew Giles piano DDD © & 2016 SOMM RECORDINGS · THAMES DITTON · SURREY · ENGLAND Made in the EU SCRIABIN PIANO SONATAS DISC 1 [74:34] SONATA NO. 5, Op. 53 (1907) bo Allegro. Impetuoso. Con stravaganza – Languido – 12:05 SONATA NO. 1 in F Minor, Op. 6 (1892) [23:58] Presto con allegrezza 1 I. Allegro Con Fuoco 9:13 2 II. Crotchet=40 (Lento) 5:01 3 III.