Programnotes Tchaikovsky Sy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-7-2018 12:30 PM Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse Renee MacKenzie The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nolan, Catherine The University of Western Ontario Sylvestre, Stéphan The University of Western Ontario Kinton, Leslie The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Musical Arts © Renee MacKenzie 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation MacKenzie, Renee, "Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5572. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5572 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This monograph examines the post-exile, multi-version works of Sergei Rachmaninoff with a view to unravelling the sophisticated web of meanings and values attached to them. Compositional revision is an important and complex aspect of creating musical meaning. Considering revision offers an important perspective on the construction and circulation of meanings and discourses attending Rachmaninoff’s music. While Rachmaninoff achieved international recognition during the 1890s as a distinctively Russian musician, I argue that Rachmaninoff’s return to certain compositions through revision played a crucial role in the creation of a narrative and set of tropes representing “Russian diaspora” following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. -

Troika.Pdf (128.9

TROIKA ALEKO, MISERLY KNIGHT, FRANCESCA DA RIMINI Composer: SERGEI RACHMANINOV ALEKO Librettist: VLADIMIR NEMIROVICH DANCHENKO, AFTER THE GYPSIES, ALEXANDER PUSHKIN Musical version: BOLSHOI THEATER, MOSKVA, 27/4/1893 Piano Score: BOOSEY & HAWKES Orchestra Score: BOOSEY & HAWKES THE MISERLY KNIGHT Librettist: ALEXANDER PUSHKIN Musical version: BOLSHOI THEATER, MOSKVA, 11/1/1906 Piano score: EDITION RUSSE DE MUSIQUE VIA B & H Orchestra score: EDITION RUSSE DE MUSIQUE VIA B & H FRANCESCA DA RIMINI Librettist: MODEST TCHAIKOVSKY AFTER DANTE Musical version: BOLSHOI THEATER, MOSKVA, 11/1/1906 Piano score: BOOSEY & HAWKES Orchestra score: BOOSEY & HAWKES Timing: 1H/50MIN/1H – 3H40 INCLUDING 2 INTERMISSIONS Production by: THÉÂTRE ROYAL DE LAMONNAIE-DEMUNT Season: 2014/2015 Storage: BRUSSELS Premièred at Théâtre National for LaMonnaie-DeMunt on 16 June 2015 sets destroyed ; costumes and video available for rent and sale ARTISTIC TEAM Conductor: MIKHAIL TATARNIKOV Stage director: KIRSTEN DEHLHOLM (Hotel pro Forma) Co-director: JON R. SKULBERG Sets: MAJA ZISKA Costumes: MANON KÜNDIG Lighting: JESPER KONGSHAUG Video: MAGNUS PIND BJERRE Dramaturg: KRYSTIAN LADA CAST Aleko Principals: ♂:3 ♀:2 Chorus: ♂:22 ♀:18 The Miserly knight Principals: ♂:5 Chorus: 0 Francesca da Rimini Principals: ♂:4 ♀:1 Chorus: ♂:22 ♀:18 SCENERY/PROPS Number oF containers: 1 For costumes ORCHESTRA COSTUMES & MAKE UP Violin I: 12 Aleko Violin II: 11 Aleko: 1 Alto: 8 Young gipsy: 1 Cello: 7 Old gipsy: 1 Contrabass: 5 ZemFira: 1 Flute: 3 Gipsy woman: 1 Oboe: 3 Chorus: ♂:22 ♀:18 -

The Phiiharmonic-Symphony Society 1842 of New York Consolidated 1928

THE PHIIHARMONIC-SYMPHONY SOCIETY 1842 OF NEW YORK CONSOLIDATED 1928 1952 ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH SEASON 1953 Musical Director: DIMITRI MITROPOULOS Guest Conductors: BRUNO WALTER, GEORGE SZELL, GUIDO CANTELLI Associate Conductor: FRANCO AUTORI For Young People’s Concerts: IGOR BUKETOFF CARNEGIE HALL 5176th Concert SUNDAY AFTERNOON, APRIL 19, 1953, at 2:30 Under the Direction of DIMITRI MITROPOULOS Assisting Artist: ARTUR RUBINSTEIN, Pianist FRANCK-PIERNE Prelude, Chorale and Fugue SCRIABIN The Poem of Ecstasy, Opus 54 Intermission SAINT-SAËNS Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 2, G minor, Opus 22 I. Andante sostenuto II. Allegretto scherzando III. Presto Artur Rubinstein FRANCK Symphonic Variations for Piano and Orchestra Artur Rubinstein (Mr. Rubinstein plays the Steinway Piano) ARTHUR JUDSON, BRUNO ZIRATO, Managers THE STEINWAY is the Official Piano of The Philharmonic-Symphony Society COLUMBIA AND VICTOR RECORDS THE PHILHARMONIC-SYMPHONY SOCIETY OF NEW YORK BOARD OF DIRECTORS •Floyd G. Blair........ ........President •Mrs. Lytle Hull... Vice-President •Mrs. John T. Pratt Vice-President ♦Ralph F. Colin Vice-President •Paul G. Pennoyer Vice-President ♦David M. Keiser Treasurer •William Rosenwald Assistant Treasurer •Parker McCollester Secretary •Arthur Judson Executive Secretary Arthur A. Ballantine Arthur A. Houghton, Jr. Mrs. William C. Breed Mrs. Arthur Lehman Chester Burden Mrs. Henry R. Luce •Mrs. Elbridge Gerry Chadwick David H. McAlpin Henry E. Coe Richard E. Myers Pierpont V. Davis William S. Paley Maitland A. Edey •Francis T. P. Plimpton Nevil Ford Mrs. David Rockefeller Mr. J. Peter Grace, Jr. Mrs. George H. Shaw G. Lauder Greenway Spyros P. Skouras •Mrs. Charles S. Guggenheimer •Mrs. Frederick T. Steinway •William R. -

Order Form Package Pricing*

NEW YORK 2016 2017 SEASON PACKAGE ORDER FORM NUMBER 1ST CHOICE 1ST CHOICE 2ND CHOICE 2ND CHOICE SUB * OF SEATS LOCATION PRICE LOCATION PRICE PRICING TOTAL ALEKO/PAGLIACCI Rose Theater, Jazz at Lincoln Center ON SALE NOW! * Does not apply to multiple dates September 8 at 7:30pm of same production. September 10 at 7:30pm September 11 at 4:00pm CREATE YOUR OWN September 13 at 7:30pm SEASON PACKAGE NEW YORK CITY OPERA CONCERTS “PASIÓN LATINA” The Appel Room, Jazz at Lincoln Center 10% of when you buy 3 Events* October 26 at 7:30pm 15% of when you buy 4 Events* CANDIDE Rose Theater, Jazz at Lincoln Center 20% of when you buy 6 Events* January 6 at 7:30pm January 7 at 2:00pm January 7 at 8:00pm EARLY BIRD SPECIAL January 8 at 4:00pm Order by September 14, 2016 and get an early January 11 at 7:30pm bird discount on Create Your Own Packages January 12 at 7:30pm 20% of when you buy 3 Events* NEW YORK CITY OPERA CONCERTS “VALENTINE’S CONCERT” The Appel Room, Jazz at Lincoln Center 25% of when you buy 4 Events* February 14 at 7:00pm 30% of when you buy 6 Events* LA CAMPANA SOMMERSA Rose Theater, Jazz at Lincoln Center March 31 at 7:30pm Single Ticket Pricing on reverse side. April 1 at 8:00pm April 4 at 7:30pm April 5 at 7:30pm ROSE THEATER ANGELS in AMERICA Rose Theater, Jazz at Lincoln Center JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER June 10 at 8:00pm Orchestra Prime $150 / $125 June 12 at 7:30pm June 14 at 7:30pm Orchestra Rear $95 / $75 June 16 at 7:30pm Orchestra Boxes $150 / $95 Mezzanine Boxes $125 / $95 / $75 SUB-TOTAL Mezzanine $75 / $55 EARLY BIRD DISCOUNT by 9/14/2016: 20% of 3 Events, 25% of 4 Events, 30% of 6 Events Balcony Boxes $55 / $20 PACKAGE DISCOUNT after 9/14/2016: 10% of 3 Events, $15% of 4 Events, 20% of 6 Events Balcony $25 / $20 FACILITY FEE: $3.50 x number of tickets HANDLING FEE $10 THE APPEL ROOM CONTRIBUTION to The People’s Fund ** JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER TOTAL Orchestra Prime $95 / $65 Orchestra Rear $35 ** The People’s Fund enables City Opera to ensure that every production will have tickets starting at $20 or $25. -

Symphony (In One Movem Ent), Op

ONE MOVEMENT SYMPHONIES BARBER SIBELIUS SCRIABIN MICHAEL STERN KANSAS CITY SYMPH ONY A ‘PROF’ JOHNSON RECORDING SAMUEL BARBER First Symphony (In One Movem ent), Op. 9 (1936) Samuel Barber was born on March 9, 1910 in West Chester, Pennsylvania. His father was a physician and his mother a sister of the famous American contralto, Louise Homer. From the time he was six years old, Barber’s musical gifts were apparent, and at the age of 13 he was accepted as one of the first students to attend the newly established Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. There he studied with Rosario Scalero (composition), Isabelle Vengerova (piano), and Emilio de Gogorza (voice). Although he began composing at the age of seven, he undertook it seriously at 18. Recognition of his gifts as a composer came quickly. In 1933 the Philadelphia Orchestra played his Overture to The School for Scandal and in 1935 the New York Philharmonic presented his Music for a Scene from Shelley . Both early compositions won considerable acclaim. Between 1935 and 1937 Barber was awarded the Prix de Rome and the Pulitzer Prize. He achieved overnight fame on November 5, 1938 when Arturo Toscanini conducted the NBC Symphony Orchestra in Barber’s Essay for Orchestra No. 1 and Adagio for Strings . The Adagio became one of the most popular American works of serious music, and through some lurid aberration of circumstance, it also became a favorite selection at state funerals and as background for death scenes in movies. During World War II, Barber served in the Army Air Corps. -

Rachmaninoff and the Flexibility of the Score: Issues Regarding Performance Practice

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Rachmaninoff and the Flexibility of the Score: Issues Regarding Performance Practice Tanya Gabrielian The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2762 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] RACHMANINOFF AND THE FLEXIBILITY OF THE SCORE: ISSUES REGARDING PERFORMANCE PRACTICE by TANYA GABRIELIAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2018 Ó 2018 TANYA GABRIELIAN All Rights Reserved ii Rachmaninoff and the Flexibility of the Score: Issues Regarding Performance Practice by Tanya Gabrielian This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Date Anne Swartz Chair of Examining Committee Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Geoffrey Burleson Sylvia Kahan Ursula Oppens THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Rachmaninoff and the Flexibility of the Score: Issues Regarding Performance Practice by Tanya Gabrielian Advisor: Geoffrey Burleson Sergei Rachmaninoff’s piano music is a staple of piano literature, but academia has been slower to embrace his works. Because he continued to compose firmly in the Romantic tradition at a time when Debussy, Stravinsky, and Schoenberg variously represented the vanguard of composition, Rachmaninoff’s popularity has consequently not been as robust in the musicological community. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 75, 1955-1956, Trip

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN I88I BY HENRY LEE HI 1955 1956 SEASON Veterans Memorial Auditorium, Providence Boston Symphony Orchestra (Seventy-fifth Season, 1955-1956) CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director RICHARD BURGIN, Associate Conductor PERSONNEL Violins Violas Bassoons Richard Burgin Joseph de Pasquale Sherman Walt Concert-master Jean Cauhape Ernst Panenka Alfred Krips Eugen Lehner Theodore Brewster George Zazofsky Albert Bernard Contra-Bassoon Rolland Tapley George Humphrey Richard Plaster Norbert Lauga Jerome Lipson Robert Karol Vladimir Resnikoff Horns Harry Dickson Reuben Green James Stagliano Gottfried AVilfinger Bernard Kadinoff Charles Yancich Einar Hansen Vincent Mauricci Harry Shapiro Joseph Leibovici John Fiasca Harold Meek Emil Kornsand Violoncellos Paul Keaney Roger Shermont Osbourne McConathy Samuel Mayes Minot Beale Alfred Zighera Herman Silberman Trumpets Jacobus Langendoen Roger Voisin Stanley Benson Mischa Nieland Leo Panasevich Marcel Lafosse Karl Zeise Armando Ghitalla Sheldon Rotenberg Josef Zimbler Gerard Goguen Fredy Ostrovsky Bernard Parronchi Clarence Knudson Leon MarjoUet Trombones Pierre Mayer Martin Hoherman William Gibson Manuel Zung Louis Berger William Moyer Kauko Kabila Samuel Diamond Richard Kapuscinski Josef Orosz Victor Manusevitch Robert Ripley James Nagy Flutes Tuba Melvin Bryant Doriot Anthony Dwyer K. Vinal Smith Lloyd Stonestreet James Pappoutsakis Saverio Messina Phillip Kaplan Harps William Waterhouse Bernard Zighera Piccolo William Marshall Olivia Luetcke Leonard Moss George Madsen Jesse -

GULF COAST REGION AUDITIONS SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 2021 the 2020 National Council Finalists Photo: Fay Fox / Met Opera

NATIONAL COUNCIL 2020–21 SEASON GULF COAST REGION AUDITIONS SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 2021 The 2020 National Council Finalists photo: fay fox / met opera CAMILLE LABARRE NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS chairman The Metropolitan Opera National Council AuDitions program cultivates young opera CAROL E. DOMINA singers and assists in the development of their careers. The AuDitions are held annually president in 39 districts and 12 regions of the United States, CanaDa, and Mexico—all aDministered MELISSA WEGNER by deDicated National Council members and volunteers. Winners of the region auDitions executive director advance to compete in the national semifnals. National fnalists are then selected and BRADY WALSH compete in the Grand Finals Concert. During the 2020–21 season, the auDitions are being administrator held virtually via livestream. Singers compete for prize money and receive feeDback from LISETTE OROPESA juDges at all levels of the competition. national advisor Many of the worlD’s greatest singers, among them Lawrence Brownlee, Anthony Roth Costanzo, Renée Fleming, Lisette Oropesa, Eric Owens, anD FreDerica von StaDe, have won National Semifnals the AuDitions. More than 100 former auDitioners appear appear on the Met roster each season. SunDay, May 9, 2021 The National Council is grateful to its donors for prizes at the national level and to the Tobin Grand Finals Concert Endowment for the Mrs. Edgar Tobin Award, given to each frst-place region winner. SunDay, May 16, 2021 Support for this program is generously proviDed by the Charles H. Dyson National Council For up to date auDitions results, alumni AuDition Program EnDowment Fund at the Metropolitan Opera. news, and other general information, follow @MONCAuDitions on Facebook and Instagram. -

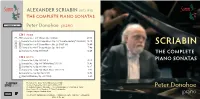

Scriabin (1872-1915) the Complete Piano Sonatas

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN (1872-1915) THE COMPLETE PIANO SONATAS SOMMCD 262-2 Peter Donohoe piano CD 1 [74:34] 1 – 4 Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 6 (1892) 23:58 5 – 6 Sonata No. 2 in G Sharp Minor, Op. 19, “Sonata-Fantasy” (1892-97) 12:10 7 – bl Sonata No. 3 in F Sharp Minor, Op. 23 (1897-98) 18:40 SCRIABIN bm – bn Sonata No. 4 in F Sharp Major, Op. 30 (1903) 7:40 bo Sonata No. 5, Op. 53 (1907) 12:05 THE COMPLETE CD 2 [65:51] 1 Sonata No. 6, Op. 62 (1911) 13:13 PIANO SONATAS 2 Sonata No. 7, Op. 64, “White Mass” (1911) 11:47 3 Sonata No. 8, Op. 66 (1912-13) 13:27 4 Sonata No. 9, Op. 68, “Black Mass” (1912-13) 7:52 5 Sonata No. 10, Op. 70 (1913) 12:59 6 Vers La Flamme, Op. 72 (1914) 6:29 TURNER Recorded live at the Turner Sims Concert Hall SIMS Southampton on 26-28 September 2014 and 2-4 May 2015 Recording Producer: Siva Oke ∙ Recording Engineer: Paul Arden-Taylor Peter Donohoe Front Cover: Peter Donohoe © Chris Cristodoulou Design & Layout: Andrew Giles piano DDD © & 2016 SOMM RECORDINGS · THAMES DITTON · SURREY · ENGLAND Made in the EU SCRIABIN PIANO SONATAS DISC 1 [74:34] SONATA NO. 5, Op. 53 (1907) bo Allegro. Impetuoso. Con stravaganza – Languido – 12:05 SONATA NO. 1 in F Minor, Op. 6 (1892) [23:58] Presto con allegrezza 1 I. Allegro Con Fuoco 9:13 2 II. Crotchet=40 (Lento) 5:01 3 III. -

Alexander Scriabin (1871-1915): Piano Miniature As Chronicle of His

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN (1871-1915): PIANO MINIATURE AS CHRONICLE OF HIS CREATIVE EVOLUTION; COMPLEXITY OF INTERPRETIVE APPROACH AND ITS IMPLICATIONS Nataliya Sukhina, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2008 APPROVED: Vladimir Viardo, Major Professor Elvia Puccinelli, Minor Professor Pamela Paul, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Sukhina, Nataliya. Alexander Scriabin (1871-1915): Piano miniature as chronicle of his creative evolution; Complexity of interpretive approach and its implications. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2008, 86 pp., 30 musical examples, 3 tables, 1 figure, references, 70 titles. Scriabin’s piano miniatures are ideal for the study of evolution of his style, which underwent an extreme transformation. They present heavily concentrated idioms and structural procedures within concise form, therefore making it more accessible to grasp the quintessence of the composer’s thought. A plethora of studies often reviews isolated genres or periods of Scriabin’s legacy, making it impossible to reveal important general tendencies and inner relationships between his pieces. While expanding the boundaries of tonality, Scriabin completed the expansion and universalization of the piano miniature genre. Starting from his middle years the ‘poem’ characteristics can be found in nearly every piece. The key to this process lies in Scriabin’s compilation of certain symbolical musical gestures. Separation between technical means and poetic intention of Scriabin’s works as well as rejection of his metaphysical thought evolution result in serious interpretive implications. -

Prometheus” and the Russian Symbolist Poetics of Light

The Poet of Fire: Aleksandr Skriabin’s Synaesthetic Symphony “Prometheus” and the Russian Symbolist Poetics of Light Polina D. Dimova Summer 2009 Polina D. Dimova is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Comparative Literature at the University of California, Berkeley Jean Delville, Cover Illustration for the Original Score of Aleksandr Skriabin’s “Prometheus: A Poem of Fire” Acknowledgements The writing of this essay on Aleksandr Skriabin and Russian Symbolism would not have been possible without the guidance, thought-provoking discussions, and meticulous readings of my dissertation committee—my advisor, Professor Eric Naiman; Professor Robert P. Hughes; Professor Barbara Spackman; and Professor Richard Taruskin. I was generously funded by a Graduate Division Summer Grant from UC Berkeley for my research trip to Moscow in 2006. I want to express my gratitude to the researchers and staff at The Aleksandr Skriabin State Museum, Moscow, for allowing me to access archival print and video materials, concerning Skriabin’s “Prometheus,” as well as for kindly offering their help and expertise. I have been fortunate to discuss specialized sections of my work with William Quillen, a Berkeley Ph.D. Candidate in Musicology and Donovan Lee, a Berkeley Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. Abstract: This paper discusses the synaesthetically informed metaphors of light, fire, and the Sun in Russian Symbolism and shows their scientific, technological, and cultural resonance in the novel experience of electric light in Russia. The essay studies the harmonic synaesthetics of Aleksandr Skriabin’s symphony “Prometheus, A Poem of Fire”—which also includes an enigmatic musically notated part for an electric organ of lights, along with Symbolist texts concerning light and electricity and the synaesthetic poetry of fire by Skriabin’s close associate Konstantin Bal’mont. -

RUSSIAN Symphonies TCHAIKOVSKY • BORODIN • PROKOFIEV • MYASKOVSKY • SHOSTAKOVICH RIMSKY-KORSAKOV • RACHMANINOV • SCRIABIN • GLAZUNOV • KALINNIKOV

GREAT RUSSIAN SYMPHONIES TCHAIKOVSKY • BORODIN • PROKOFIEV • MYASKOVSKY • SHOSTAKOVICH RIMSKY-KORSAKOV • RACHMANINOV • SCRIABIN • GLAZUNOV • KALINNIKOV 1 8.501059 Rimsky-Korsakov acquired a high degree of musical expertise, helped by leaving the GREAT RUSSIAN SYMPHONIES navy and taking up a position as inspector of naval bands. He remained the most fully professional of the Five, with particular skill in orchestration. In the nature of things TCHAIKOVSKY • BORODIN • PROKOFIEV • MYASKOVSKY Borodin, Mussorgsky and Cui had to combine their careers with composition. Cui, a SHOSTAKOVICH • RIMSKY-KORSAKOV harsh critic, excelled in shorter, genre pieces, while the first two left much unfinished at RACHMANINOV • SCRIABIN • GLAZUNOV • KALINNIKOV their deaths, works to be revised and completed by Rimsky-Korsakov. The Russian composers who followed were able to benefit both from the teaching INTRODUCTION of the Conservatories and from the ideals of the nationalists, but later generations were greatly affected by the course of Russian politics. The first Russian revolution of 1905 had found Rimsky-Korsakov siding with the students in a political disturbance that, for The mid-nineteenth century brought increasing awareness of national identities the time being, lost him his position at the St Petersburg Conservatory. The resulting throughout Europe and not least in Russia. Led by Balakirev, a group of five nationalist constitutional settlement lasted until the final victory of the Bolsheviks in the October Russian composers, described by the polymath Vladimir Stasov as Mogushka, the Revolution of 1917. The establishment of a socialist régime in Russia changed the Mighty Handful, and otherwise known as The Five, worked intermittently together course of Russian music and the lives of Russian musicians.