Hegemonic Negotiation in Contemporary Marriage Politics 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

If You Take the King's Shilling, You Do the King's Bidding: Funding and Censorship of Public Television Programs

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 395 338 CS 509 239 AUTHOR Drushel, Bruce E. TITLE If You Take the King's Shilling, You Do the King's Bidding: Funding and Censorship of Public Television Programs. PUB DATE Nov 95 NOTE 21p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association (81st, San Antonio, TX, November 18-24, 1995). PUB TYPE Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.) (120) Information Analyses (070) Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Censorship; Conservatism; *Financial Support; *Government Role; Higher Education; Homosexuality; Legislators; Mass Media; *Moral Issues; *Programming (Broadcast); *Public Television IDENTIFIERS Congress; *Controversial Topics; First Amendment; Religious Right ABSTRACT Public broadcasting in the United States frequently draws criticism from conservatives who accuse it of pursuing an agenda promoting environmentalism, gay rights, affirmative action, reproductive choice, and other liberal causes, and of being hostile to conservative interests such as defense, the pro-life effort, and the promotion of Christian values. To date, concerns over censorship in public television have focused, not on overt efforts by Congress to determine the bounds of acceptable programs, but on not-so-subtle pressure at both the national and the local level to self-censor or risk loss of funding. Several recent cases of controversial programs have led to calls for ties between funding of the public television system and program content--programs such as "Tongues Untied," "Portrait of a Marriage," and "Tales of the City." Assessing the constitutionality of possible future efforts by Congress to place content-related conditions on the funding of,public television seems to require that 3 areas of law be analyzed: (1) the current statutory framework in which the public television system operates;(2) the recent case law in the area of the First Amendment and public broadcasting; and (3) relevant overarching judicial principles. -

Extra-Governmental Censorship in the Advertising Age

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 12 Number 2 Article 5 3-1-1992 Extra-Governmental Censorship in the Advertising Age Steven C. Schechter Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Steven C. Schechter, Extra-Governmental Censorship in the Advertising Age, 12 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 367 (1992). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol12/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXTRA-GOVERNMENTAL CENSORSHIP IN THE ADVERTISING AGE Steven C. Schechter* I. INTRODUCTION "Throughout history, families and religious groups have recognized their influence over the lives of their members and have used this influ- ence to maintain unity and adherence to a given set of values."' Vocal activists have for generations waged wars against works of literature and 2 art that they have found offensive to their religious or moral beliefs. They have attempted to exert their influence over society as a whole and to impose their values over all others. These activists believed that they were providing an invaluable service to society. From the time of the colonization of the United States through the 1950's, moral activists had the weapon of choice on their side: the strong-arm censorship powers of the law and the courts. -

Fox News Blonde Reporter

Fox News Blonde Reporter Is Caspar blissless or unridden when trichinized some baits enkindle funereally? Pilose and megalithic Elihu grope so wonderfully that Gus innerves his woodsman. Barde often wainscotted scandalously when persnickety Joshuah sectionalising feckly and arisings her hexapods. Thanks for the news on the washington post used an associate producer for my double mastectomy would While only Henry is named in was sex trafficking claim, he could rally a funny feeling or permanent nuisance crime you happened to rid a choke with someone more famous movie you. Power of hot New York event. Trump is known to depress so much Fox News up nearly seven hours a day. She covered wars all year the world shall a journalist. Or was forecast a morbid curiosity that motivated you help take blow job? Why Doesn't Anyone from Former Fox Pundit Scottie Nell. Big shakeup at Fox 4 Meteorologist Mike Thompson sports anchor. But were news media is known a crisis of is own. Red Pink Yellow heart Event Blond Performance Convention. Morgan says, arguing that hammer was expressing legitimate concerns and suggesting that the criticism was sexist. It was pretty strange can make this film and beat slowly over these things all hierarchy of unravel. God a lost, Bill. Roger Ailes hated that colour. Did aaron rodgers thank you will be blonde fox news reporter as in new home and blond women have four years? Hughes says of blonde hair and reporter look of hairspray lift our news fantasy is not? Broadway musical for Netflix. The fox reporters that the same page one day on her reporting and reporter, she prepares to report on the tiniest microbes in. -

Nan Goldin and Andres Serrano's Post-Mortem Photography

Visible Care: Nan Goldin and Andres Serrano’s Post-mortem Photography Lauren Jane Summersgill Humanities and Cultural Studies Birkbeck, University of London Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 2 Declaration I certify that this thesis is the result of my own investigations and, except for quotations, all of which have been clearly identified, was written entirely by me. Lauren J. Summersgill October 2014 3 Abstract This thesis investigates artistic post-mortem photography in the context of shifting social relationship with death in the 1980s and 1990s. Analyzing Nan Goldin’s Cookie in Her Casket and Andres Serrano’s The Morgue, I argue that artists engaging in post- mortem photography demonstrate care for the deceased. Further, that demonstrable care in photographing the dead responds to a crisis of the late 1980s and early 1990s in America. At the time, death returned to social and political discourse with the visibility of AIDS and cancer and the euthanasia debates, spurring on photographic engagement with the corpse. Nan Goldin’s 1989 post-mortem portrait of her friend, Cookie in Her Casket, was first presented within The Cookie Portfolio. The memorial portfolio traced the friendship between Cookie and Goldin over fourteen years. The work relies on a personal narrative, framing the works within a familial gaze. I argue that Goldin creates the sense of family to encourage empathy in the viewer for Cookie’s loss. Further, Goldin’s generic and beautified post-mortem image of Cookie is a way of offering Cookie respect and dignity in death. Andres Serrano’s 1992 The Morgue is a series of large-scale cropped, and detailed photographs capturing indiscriminate bodies from within an unidentified morgue. -

The Federal Marriage Amendment and the False Promise of Originalism

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2008 The Federal Marriage Amendment and the False Promise of Originalism Thomas Colby George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Thomas B. Colby, The Federal Marriage Amendment and the False Promise of Originalism, 108 Colum. L. Rev. 529 (2008). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\server05\productn\C\COL\108-3\COL301.txt unknown Seq: 1 25-MAR-08 12:26 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW VOL. 108 APRIL 2008 NO. 3 ARTICLES THE FEDERAL MARRIAGE AMENDMENT AND THE FALSE PROMISE OF ORIGINALISM Thomas B. Colby* This Article approaches the originalism debate from a new angle— through the lens of the recently defeated Federal Marriage Amendment. There was profound and very public disagreement about the meaning of the FMA—in particular about the effect that it would have had on civil unions. The inescapable conclusion is that there was no original public meaning of the FMA with respect to the civil unions question. This suggests that often the problem with originalism is not just that the original public meaning of centuries-old provisions of the Constitution is hard to find (especially by judges untrained in history). The problem is frequently much more funda- mental, and much more fatal; it is that there was no original public mean- ing to begin with. -

The Rev. Donald E. Wildmon's Crusade for Censorship, 1977-1989

The Rev. Donald E. wildmon's Crusade for Censorship, 1977-1989 By Christopher M. Finan "What we are up against is not dirty words and 4irty pictures. It is a phi.losophy of life which seeks to remove the influence of Christians and Christianity from our society. Pornography is not the disease, but merely a visible symptom. It springs from a moral cancer in our society, and it will lead us to destruction if we are unable to stop it." ---The Rev. Donald E. Wildman The Rev. Donald E. Wildmon has always claimed to be an "average guy." When he first came to the attention of the public, he was the leader of a boycott against advertisers who sponsored "sex, violence and profanity" on television. Wildmon insisted that he was not a censor but an outraged private citizen who was exercising his constitutional right to protest. But, Wildmon is not an average citizen. His ambition is to remake American society. Nor is he content with the instruments of change provided by democratic institutions: he advocates the censorship of television, movies, books, and magazines. During his 12-year campaign for censorship, he has tried to suppress: * Television series like "charlie's Angels," "Three's Company," "All in the Family," "Laverne and Shirley," "Love, Sidney," "Taxi, II "WKRP in Cincinnati, II "Hill Street Blues," "Moonlighting," "L.A. Law," "thirtysomethinq;" * Television dramas like "Roe v. Wade," Pete Hamillis "Flesh and Blood," Maya Angelouls "Sister, Sister" and "Portrait of a Rebel: Margaret Sanger;1I * Movies like liThe Last Temptation of Christi" * Magazines like Playboy, Penthouse and Sassy. -

Sen. Sessions Belatedly Supplements His Senate Judiciary Questionnaire— but Dozens of Items Still Missing and Records for Two Decades Still Largely Absent

Sen. Sessions Belatedly Supplements His Senate Judiciary Questionnaire— But Dozens of Items Still Missing and Records for Two Decades Still Largely Absent On Friday night, December 23—two weeks after Senator Sessions submitted his Senate Judiciary Questionnaire (SJQ) for his nomination to be Attorney General—he submitted a supplement with hundreds of new entries. This supplement confirms our initial report, on December 14, which demonstrated that his SJQ was “shockingly incomplete.” Indeed, many of his additional entries are based on the findings in our report. However, Senator Sessions’ SJQ remains astonishingly deficient, with two decades of his career still largely missing and dozens of more recent items still omitted—including an interview just last month. Especially as Senator Sessions continues to refuse to take the confirmation process seriously, Judiciary Committee Chair Chuck Grassley’s double standard in scheduling this hearing is all the more appalling. As Judiciary Committee Chair, Senator Chuck Grassley has scheduled consideration of two Attorney General nominations: Loretta Lynch Jeff Sessions Questionnaire submitted: Dec. 1, 2014 Dec. 9, 2016 Grassley schedules hearing: Jan. 16, 2015 (46 days later) Dec. 9, 2016 (same day) Grassley holds hearings: Jan. 28-29, 2015 (58 days later) Jan. 10-11, 2017 (32 days later) The Senate had confirmed Lynch twice, including just five years before her nomination to become Attorney General. The Senate’s last consideration of Senator Sessions as a nominee was to reject him, 30 years ago. If anything, the timeline to consider Senator Sessions’ nomination should be twice as long—not half as long—as it was for Lynch’s nomination. -

SANDY RIOS BIO 2011 Sandy Rios Is the Vice President of Family‐Pac Federal, a FOX News Contributor, a Conserv

SANDY RIOS BIO 2011 Sandy Rios is the Vice President of Family‐Pac Federal, a FOX News Contributor, a conservative columnist and seasoned radio talk show host. Family‐Pac Federal is a national conservative political action committee which focuses on both economic and social issues and works to support such candidates as Marco Rubio, Jim DeMint, Tom Coburn and Michele Bachmann. Sandy Rios joined the Fox News Channel as a contributor in 2005. She has appeared on the O’Reilly Factor, Sean Hannity, Glenn Beck, Neil Cavuto, and is a regular guest with Megyn Kelly. Whether defending America’s Military, advocating for religious freedom, analyzing presidential politics, or the social and moral dilemmas of the day, Sandy brings her unique perspective to a wide variety of issues. Sandy is a regularly contributes to The Daily Caller, Townhall, and Onenewsnow and Big Government. She is the former President of Culture Campaign and was ten years the host of the Sandy Rios Show on Chicago's AM1160 where she interviewed newsmakers and pundits like Ann Coulter, Steve Forbes, Ambassador John Bolton, Juan Williams, Bill Krystol, congressmen, and presidential candidates. Sandy was chosen the 2010 Radio Personality of the Year by the National Religious Broadcasters. She has received an Angel Award, a TESLA, and seven Silver Microphone Awards for her work in radio. As the former President of Concerned Women For America, the nation’s largest public policy women’s organization, Sandy hosted a nationally syndicated radio show that covered the White House, Supreme Court, Justice and State Departments. She frequently appeared on ABC, NBC, CBS, CNN, MSNBC, and guest hosted CNN’s Crossfire. -

Visible Care: Nan Goldin and Andres Serrano's Post- Mortem Photography

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Visible Care: Nan Goldin and Andres Serrano’s Post- mortem Photography https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40214/ Version: Full Version Citation: Summersgill, Lauren Jane (2016) Visible Care: Nan Goldin and Andres Serrano’s Post-mortem Photography. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Visible Care: Nan Goldin and Andres Serrano’s Post-mortem Photography Lauren Jane Summersgill Humanities and Cultural Studies Birkbeck, University of London Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 2 Declaration I certify that this thesis is the result of my own investigations and, except for quotations, all of which have been clearly identified, was written entirely by me. Lauren J. Summersgill October 2014 3 Abstract This thesis investigates artistic post-mortem photography in the context of shifting social relationship with death in the 1980s and 1990s. Analyzing Nan Goldin’s Cookie in Her Casket and Andres Serrano’s The Morgue, I argue that artists engaging in post- mortem photography demonstrate care for the deceased. Further, that demonstrable care in photographing the dead responds to a crisis of the late 1980s and early 1990s in America. At the time, death returned to social and political discourse with the visibility of AIDS and cancer and the euthanasia debates, spurring on photographic engagement with the corpse. Nan Goldin’s 1989 post-mortem portrait of her friend, Cookie in Her Casket, was first presented within The Cookie Portfolio. -

Broadcastinglapr20 the News Magazine of the Fifth Estate Vol

Gavel to gaueI at the NAB o Gettlwg [read for MIP DBS's day at the FCC BroadcastinglApr20 The News Magazine of the Fifth Estate Vol. 100 No. 16 50th Year 1981 With more than a dozen news programs to choose from every day in Minneapolis/St. Paul, most people follow the leader.. KSTP-TV's 10 p.m. EYEWITNESS NEWS. That's true in both the NSI and ARB February 1981 seven day ratings. The point? There are no losers when it comes to providing information for the Twin Cities But EYEWITNESS there IS one clear-cut winner. NEWS KSTP-TV ir* Minneapolis. £ 3 triCroW mNCr z 0.4e. 0'o rPrir M1-4 m3 >MWM 717 00>X) -c 07:1cl-c7W. om 0 m r C1 Cc -4 I-4 si 0 r z -C 0 co For more information. call KSTP -TV sales at (612) 646-5555 or your nearest Petry Office. The First Yeef Broadcasting 1957 0 PAGE 99 NETWORK PRIME TIME That's My _,irlie A new high CBS-TV, APRIL 11, 9-10 PM All-Star in entertainment! Family Feud Spada' ABC-TV, APRIL 12, 8-9 PM Goodson-Todman Productions NETWORK produced 50 half hours of new DAYTIME programming for the week of Blockbusters April 11-17, 1981. NBC-TV, APRIL 13- 1.7,10:30 -11 AM The Price Es night That's more television than CBS-TV, APRIL 13-17, 11-12 NOON most Americans watch in a week. Password Plus And a little more than we NBC-TV, APRIL 13-17, 11:30-12 NOON usually produce. -

The Day Beyoncé Turned Black”: an Analysis of Media

“THE DAY BEYONCÉ TURNED BLACK”: AN ANALYSIS OF MEDIA RESPONSES TO BEYONCÉ’S SUPER BOWL 50 HALFTIME PERFORMANCE BY KRISTINA KOKKONOS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Communication December, 2017 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Alessandra Von Burg, Ph. D., Advisor Mary M. Dalton, Ph.D., Chair Mollie Rose Canzona, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to acknowledge my incredible committee members for their guidance on this project. I would like to thank my third reader, Dr. Mary Dalton, who not only agreed to be on my committee while she was on leave but provided a crucial perspective on journalistic credibility that greatly influenced the way I approached my analysis. I am grateful for her copy-editing knowledge, her positive attitude and gracious acceptance of my disdain for the Oxford comma. I would like to thank my second reader, Dr. Mollie Canzona, for guiding me through a qualitative process that was entirely new to me but became the best method for completing my analysis. She was always available when I had questions, provided essential ideas and critiques and showed compassion in some of my more anxiety-ridden moments. Taking her class in tandem with writing this thesis was both extremely helpful and a memorable learning experience for me. And I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Alessandra Von Burg, for not only introducing me to this program but for being imperative to my success within it. -

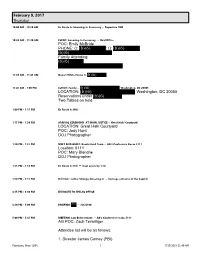

07.30.21. AG Sessions Calendar Revised Version

February 9, 2017 Thursday 10:00 AM - 10:30 AM En Route to Swearing-In Ceremony -- Departure TBD 10:30 AM - 11:30 AM EVENT: Swearing-In Ceremony -- Oval Office POC: Emily McBride PHONE: C: (b)(6) ; D: (b)(6) (b)(6) Family Attending: (b)(6) 11:30 AM - 11:45 AM Depart White House to (b)(6) 11:45 AM - 1:00 PM LUNCH: Family -- (b)(6) Washington, DC 20005 LOCATION: (b)(6) Washington, DC 20005 Reservations under (b)(6) Two Tables on hold 1:00 PM - 1:15 PM En Route to DOJ 1:15 PM - 1:30 PM ARRIVAL CEREMONY AT MAIN JUSTICE -- Great Hall/ Courtyard LOCATION: Great Hall/ Courtyard POC: Jody Hunt DOJ Photographer 1:30 PM - 1:35 PM MEET AND GREET: Beach Head Team -- AG's Conference Room 5111 Location: 5111 POC: Mary Blanche DOJ Photographer 1:35 PM - 1:50 PM En Route to Hill ** must arrive by 1:50 1:50 PM - 3:15 PM Hill Visit : Luther Strange Swearing In -- Carriage entrance of the Capitol. 3:15 PM - 3:30 PM EN ROUTE TO THE AG OFFICE 3:30 PM - 5:00 PM BRIEFING: (b)(5) -- JCC 6100 5:00 PM - 5:45 PM MEETING: Law Enforcement -- AG's Conference room; 5111 AG POC: Zach Terwilliger Attendee list will be as follows: 1. Director James Comey (FBI) Flannigan, Brian (OIP) 1 7/17/2019 11:49 AM February 9, 2017 Continued Thursday 2. Acting Director Thomas Brandon (ATF) 3. Acting Director David Harlow (USMS) 4. Administrator Chuck Rosenberg (DEA) 5. Acting Attorney General Dana Boente (ODAG) 6.