FRAMING ISLAM AS a THREAT the Use of Islam by Some U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4 the Right-Wing Media Enablers of Anti-Islam Propaganda

Chapter 4 The right-wing media enablers of anti-Islam propaganda Spreading anti-Muslim hate in America depends on a well-developed right-wing media echo chamber to amplify a few marginal voices. The think tank misinforma- tion experts and grassroots and religious-right organizations profiled in this report boast a symbiotic relationship with a loosely aligned, ideologically-akin group of right-wing blogs, magazines, radio stations, newspapers, and television news shows to spread their anti-Islam messages and myths. The media outlets, in turn, give members of this network the exposure needed to amplify their message, reach larger audiences, drive fundraising numbers, and grow their membership base. Some well-established conservative media outlets are a key part of this echo cham- ber, mixing coverage of alarmist threats posed by the mere existence of Muslims in America with other news stories. Chief among the media partners are the Fox News empire,1 the influential conservative magazine National Review and its website,2 a host of right-wing radio hosts, The Washington Times newspaper and website,3 and the Christian Broadcasting Network and website.4 They tout Frank Gaffney, David Yerushalmi, Daniel Pipes, Robert Spencer, Steven Emerson, and others as experts, and invite supposedly moderate Muslim and Arabs to endorse bigoted views. In so doing, these media organizations amplify harm- ful, anti-Muslim views to wide audiences. (See box on page 86) In this chapter we profile some of the right-wing media enablers, beginning with the websites, then hate radio, then the television outlets. The websites A network of right-wing websites and blogs are frequently the primary movers of anti-Muslim messages and myths. -

Family Research Council As Amicus Curiae in Support of the Respondent ______

Nos. 18-1323 & 18-1460 In the Supreme Court of the United States _____________ JUNE MEDICAL SERVICES LLC, ET AL., Petitioners and Cross-Respondents, v. DR. REBEKAH GEE, SECRETARY, LOUISIANA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HOSPITALS, Respondent and Cross-Petitioner. _____________ ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT _____________ BRIEF OF FAMILY RESEARCH COUNCIL AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF THE RESPONDENT _____________ TRAVIS S. WEBER JONATHAN F. MITCHELL KATHERINE BECK JOHNSON Counsel of Record Family Research Council Mitchell Law PLLC 801 G Street NW 111 Congress Avenue Washington, DC 20001 Suite 400 (800) 225-4008 Austin, Texas 78701 [email protected] (512) 686-3940 [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae ! TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of contents ................................................................... i! Table of authorities ............................................................. iii! Interest of amicus curiae ...................................................... 1! Summary of argument .......................................................... 2! I.! The plaintiffs lack statutory standing to challenge Act 620 ....................................................... 5! A.! The plaintiffs must identify a cause of action that authorizes them to sue state officials who violate the constitutional rights of third parties ......................................... 6! B.! There is no cause of action that authorizes abortion providers to sue state officials who violate -

The Heritage Foundation and Family Research Council: Mirror Images of Hate

The Heritage Foundation and Family Research Council: Mirror Images of Hate The Heritage Foundation is fond of branding itself as a think tank of establishment conservatives. In reality, Heritage regularly spouts hateful ideas that are detrimental to LGBTQ individuals, women, people of color and low-income workers. Heritage’s policy positions are not dissimilar from those of peer organizations such as the Family Research Council (FRC) that have earned designation from the Southern Poverty Law Center as hate groups. More information on Heritage’s hateful policies and its influence on the Trump administration can be found in our report, “The Heritage Foundation’s Health Department: How an Increasingly Radical Right Wing Think Tank Is Controlling HHS — to the Detriment of Reproductive Health and Other Human Rights.” Policy Position Comparison Between The Heritage Foundation and the Family Research Council The Heritage Foundation Family Research Council Anti-Abortion Heritage Is Opposed to a Women's Right to FRC Believes Roe v. Wade Was Wrongly Obtain an Abortion and Works to Undermine Decided and Actively Works to Have the Women’s Access to Reproductive Healthcare Decision Reversed "Since Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton "Few things touch on the sanctity of effectively legalized abortion on demand, more human life more than the practice of than 58 million children have been denied the abortion. A pregnancy should not simply right to life. For over forty years the pro-life be 'terminated,' as if it were something community has worked to counter the impersonal and problematic and it cannot devastating impact abortion has had on be without physical and emotional mothers, fathers, and their unborn babies, consequences. -

The Lost Generation in American Foreign Policy How American Influence Has Declined, and What Can Be Done About It

September 2020 Perspective EXPERT INSIGHTS ON A TIMELY POLICY ISSUE JAMES DOBBINS, GABRIELLE TARINI, ALI WYNE The Lost Generation in American Foreign Policy How American Influence Has Declined, and What Can Be Done About It n the aftermath of World War II, the United States accepted the mantle of global leadership and worked to build a new global order based on the principles of nonaggression and open, nondiscriminatory trade. An early pillar of this new Iorder was the Marshall Plan for European reconstruction, which British histo- rian Norman Davies has called “an act of the most enlightened self-interest in his- tory.”1 America’s leaders didn’t regard this as charity. They recognized that a more peaceful and more prosperous world would be in America’s self-interest. American willingness to shoulder the burdens of world leadership survived a costly stalemate in the Korean War and a still more costly defeat in Vietnam. It even survived the end of the Cold War, the original impetus for America’s global activ- ism. But as a new century progressed, this support weakened, America’s influence slowly diminished, and eventually even the desire to exert global leadership waned. Over the past two decades, the United States experienced a dramatic drop-off in international achievement. A generation of Americans have come of age in an era in which foreign policy setbacks have been more frequent than advances. C O R P O R A T I O N Awareness of America’s declining influence became immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic and by Obama commonplace among observers during the Barack Obama with Ebola, has also been widely noted. -

In Their Own Words: Voices of Jihad

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as CHILD POLICY a public service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and PUBLIC SAFETY effective solutions that address the challenges facing SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY the public and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. in their own words Voices of Jihad compilation and commentary David Aaron Approved for public release; distribution unlimited C O R P O R A T I O N This book results from the RAND Corporation's continuing program of self-initiated research. -

Australia Muslim Advocacy Network

1. The Australian Muslim Advocacy Network (AMAN) welcomes the opportunity to input to the UN Special Rapporteur on the Freedom of Religion or Belief as he prepares this report on the Impact of Islamophobia/anti-Muslim hatred and discrimination on the right to freedom of thought, conscience religion or belief. 2. We also welcome the opportunity to participate in your Asia-Pacific Consultation and hear from the experiences of a variety of other Muslims organisations. 3. AMAN is a national body that works through law, policy, research and media, to secure the physical and psychological welfare of Australian Muslims. 4. Our objective to create conditions for the safe exercise of our faith and preservation of faith- based identity, both of which are under persistent pressure from vilification, discrimination and disinformation. 5. We are engaged in policy development across hate crime & vilification laws, online safety, disinformation and democracy. Through using a combination of media, law, research, and direct engagement with decision making parties such as government and digital platforms, we are in a constant process of generating and testing constructive proposals. We also test existing civil and criminal laws to push back against the mainstreaming of hate, and examine whether those laws are fit for purpose. Most recently, we are finalising significant research into how anti-Muslim dehumanising discourse operates on Facebook and Twitter, and the assessment framework that could be used to competently and consistently assess hate actors. A. Definitions What is your working definition of anti-Muslim hatred and/or Islamophobia? What are the advantages and potential pitfalls of such definitions? 6. -

Saudi Arabia's Curriculum of Intolerance

2008 Update Saudi Arabia’s Curriculum of Intolerance With Excerpts from Saudi Ministry of Education Textbooks for Islamic Studies Center for Religious Freedom of the Hudson Institute 2008 WITH THE INSTITUTE FOR GULF AFFAIRS 2008 Update: Saudi Arabia’s Curriculum of Intolerance Center for Religious Freedom of Hudson Institute With the Institute for Gulf Affairs 2 Copyright © 2008 by Center for Religious Freedom Published by the Center for Religious Freedom Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any manner without the written permission of the Center for Religious Freedom, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Center for Religious Freedom Hudson Institute 1015 15th Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20005 Phone: 202-974-2400 Fax: 202-974-2410 Website: http://crf.hudson.org 3 About the Center for Religious Freedom The Center for Religious Freedom promotes religious freedom as a component of U.S. foreign policy by working with a worldwide network of religious freedom experts to provide defenses against religious persecution and oppression. Since its inception in 1986, the Center has sponsored investigative field missions, reported on the religious persecution of individuals and groups abroad, and undertaken advocacy on their behalf in the media, Congress, State Department and White House. Religious freedom faces difficult new challenges. Recent decades have seen the rise of extreme interpretations of Islamist rule that are virulently intolerant of dissenting voices and other traditions within Islam, as well as other faiths. Many in the policy world still find religious freedom too "sensitive" to raise. -

Reporter Privilege: a Con Job Or an Essential Element of Democracy Maguire Center for Ethics and Public Responsibility Public Scholar Presentation November 14, 2007

Reporter Privilege: A Con Job or an Essential Element of Democracy Maguire Center for Ethics and Public Responsibility Public Scholar Presentation November 14, 2007 Two widely divergent cases in recent months have given the public some idea as to what exactly reporter privilege is and whether it may or may not be important in guaranteeing the free flow of information in society. Whether it’s important or not depends on point of view, and, sometimes, one’s political perspective. The case of San Francisco Giants baseball star Barry Bonds and the ongoing issues with steroid use fueled one case in which two San Francisco Chronicle reporters were held in contempt and sentenced to 18 months in jail for refusing to reveal the source of leaked grand jury testimony. According to the testimony, Bonds was among several star athletes who admitted using steroids in the past, although he claimed he did not know at the time the substance he was taking contained steroids. In the other, New York Times reporter Judith Miller served 85 days in jail over her refusal to disclose the source of information that identified a CIA employee, Valerie Plame. The case was complicated with political overtones dealing with the Bush Administration’s claims in early 2003 that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. A number of other reporter privilege cases were ongoing during the same time period as these two, but the newsworthiness and the subject matter elevated these two cases in terms of extensive news coverage.1 Particularly in the case of Miller, a high-profile reporter for what arguably is the most important news organization in the world, being jailed created a continuing story that was closely followed by journalists and the public. -

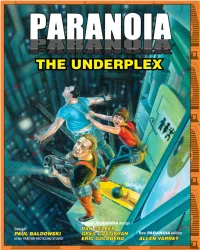

Communists (Common), Sierra Club (Uncommon) Directives—A Sequence of Directions and the Transtube Network Is the Lifeblood of Alpha Complex’S Economy

™ PARTheAN UnderplexOIA The abandoned tunnel network that interpenetrates Alpha Complex, and all the ways it can kill your PCs PAUL BALDOWSKI, Architect (www.omegacomplex.com) GREG INGBER DAN GELBER CONTENTS KARL LOW GREG COSTIKYAN Introduction 2 ERIC MINTON ERIC GOLDBERG 1. Under construction 4 Additional material and poorfreadnig/ Original game design & development/ 2. Under population 14 Contractors Building committee 3. Hook, line and sinkhole 38 4. Gear 31 BETH FISCHI IAN BELCHER Mission: ‘The One’ 35 ANDY FITZPATRICK Mongoose Publishing RPG manager/ Appendix 1: Random Underplex 46 ALLEN VARNEY Construction supervisor Appendix 2: Overfl ow 47 Editing, layout, graphics/Drillbots ALEXANDER FENNELL JIM HOLLOWAY Mongoose Publishing production director/ The ‘fortune cookies’ at the lower right of Cover and interior illustrations/Blueprints Struts around wearing fun yellow hardhat each two-page spread come from loyal citizens Paul Baldowski, Karl Low, Saul Resnikoff, Bart Savenije, Silent, and THE COMPUTER Tobias Svalborg, who answered the call on the PARANOIA development blog (www. Orders it built; seals it off; repeat costik.com/paranoia). Commendations! Security Clearance ULTRAVIOLET WARNING: Knowledge or possession of this information by any citizen of Security Clearance VIOLET or lower is treason, dark nasty skulking subterranean treason of the most deeply entrenched kind TM & Copyright © 1983, 1987, 2006 by Eric Goldberg & Greg Costikyan. All Rights Reserved. Mongoose Publishing Ltd., Authorized User. Based on material published in previous editions of PARANOIA. ILLUMINATI is a registered trademark of Steve Jackson Games, and is used by permission. The reproduction of material from this book for personal or corporate profi t, by photographic, electronic, or other means of storage and retrieval, is prohibited. -

SAY NO to the LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES and CRITICISM of the NEWS MEDIA in the 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the Faculty

SAY NO TO THE LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES AND CRITICISM OF THE NEWS MEDIA IN THE 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism, Indiana University June 2013 ii Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee David Paul Nord, Ph.D. Mike Conway, Ph.D. Tony Fargo, Ph.D. Khalil Muhammad, Ph.D. May 10, 2013 iii Copyright © 2013 William Gillis iv Acknowledgments I would like to thank the helpful staff members at the Brigham Young University Harold B. Lee Library, the Detroit Public Library, Indiana University Libraries, the University of Kansas Kenneth Spencer Research Library, the University of Louisville Archives and Records Center, the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, the Wayne State University Walter P. Reuther Library, and the West Virginia State Archives and History Library. Since 2010 I have been employed as an editorial assistant at the Journal of American History, and I want to thank everyone at the Journal and the Organization of American Historians. I thank the following friends and colleagues: Jacob Groshek, Andrew J. Huebner, Michael Kapellas, Gerry Lanosga, J. Michael Lyons, Beth Marsh, Kevin Marsh, Eric Petenbrink, Sarah Rowley, and Cynthia Yaudes. I also thank the members of my dissertation committee: Mike Conway, Tony Fargo, and Khalil Muhammad. Simply put, my adviser and dissertation chair David Paul Nord has been great. Thanks, Dave. I would also like to thank my family, especially my parents, who have provided me with so much support in so many ways over the years. -

White Male Heterosexist Norms in the Confirmation Process Theresa M

University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives Faculty Scholarship 2011 White Male Heterosexist Norms in the Confirmation Process Theresa M. Beiner University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lawrepository.ualr.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Judges Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Theresa M. Beiner, White Male Heterosexist Norms in the Confirmation Process, 32 Women's Rts. L. Rep. 105 (2011). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHITE MALE HETEROSEXIST NORMS IN THE CONFIRMATION PROCESS Theresa M Beiner* I. INTRODUCTION Justice Sonia Sotomayor's confirmation hearing took a controversial turn when commentators became aware of a reference in the New York Times to a portion of a speech she gave in 2001.1 In that speech, she candidly addressed how her background might influence her decision making opining, "I would hope that a wise Latina woman with the richness of her experiences would more often than not reach a better conclusion than a white male who hasn't lived that life." 2 Eight years later a minor . Nadine Baum Distinguished Professor of Law, Associate Dean for Faculty Development, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, William H. Bowen School of Law. -

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds an End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches