Visible Care: Nan Goldin and Andres Serrano's Post- Mortem Photography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pressemappe American Photography

Exhibition Facts Duration 24 August – 28 November 2021 Virtual Opening 23. August 2021 | 6.30 PM | on Facebook-Live & YouTube Venue Bastion Hall Curator Walter Moser Co-Curator Anna Hanreich Works ca. 180 Catalogue Available for EUR EUR 29,90 (English & German) onsite at the Museum Shop as well as via www.albertina.at Contact Albertinaplatz 1 | 1010 Vienna T +43 (01) 534 83 0 [email protected] www.albertina.at Opening Hours Daily 10 am – 6 pm Press contact Daniel Benyes T +43 (01) 534 83 511 | M +43 (0)699 12178720 [email protected] Sarah Wulbrandt T +43 (01) 534 83 512 | M +43 (0)699 10981743 [email protected] 2 American Photography 24 August - 28 November 2021 The exhibition American Photography presents an overview of the development of US American photography between the 1930s and the 2000s. With works by 33 artists on display, it introduces the essential currents that once revolutionized the canon of classic motifs and photographic practices. The effects of this have reached far beyond the country’s borders to the present day. The main focus of the works is on offering a visual survey of the United States by depicting its people and their living environments. A microcosm frequently viewed through the lens of everyday occurrences permits us to draw conclusions about the prevalent political circumstances and social conditions in the United States, capturing the country and its inhabitants in their idiosyncrasies and contradictions. In several instances, artists having immigrated from Europe successfully perceived hitherto unknown aspects through their eyes as outsiders, thus providing new impulses. -

If You Take the King's Shilling, You Do the King's Bidding: Funding and Censorship of Public Television Programs

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 395 338 CS 509 239 AUTHOR Drushel, Bruce E. TITLE If You Take the King's Shilling, You Do the King's Bidding: Funding and Censorship of Public Television Programs. PUB DATE Nov 95 NOTE 21p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association (81st, San Antonio, TX, November 18-24, 1995). PUB TYPE Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.) (120) Information Analyses (070) Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Censorship; Conservatism; *Financial Support; *Government Role; Higher Education; Homosexuality; Legislators; Mass Media; *Moral Issues; *Programming (Broadcast); *Public Television IDENTIFIERS Congress; *Controversial Topics; First Amendment; Religious Right ABSTRACT Public broadcasting in the United States frequently draws criticism from conservatives who accuse it of pursuing an agenda promoting environmentalism, gay rights, affirmative action, reproductive choice, and other liberal causes, and of being hostile to conservative interests such as defense, the pro-life effort, and the promotion of Christian values. To date, concerns over censorship in public television have focused, not on overt efforts by Congress to determine the bounds of acceptable programs, but on not-so-subtle pressure at both the national and the local level to self-censor or risk loss of funding. Several recent cases of controversial programs have led to calls for ties between funding of the public television system and program content--programs such as "Tongues Untied," "Portrait of a Marriage," and "Tales of the City." Assessing the constitutionality of possible future efforts by Congress to place content-related conditions on the funding of,public television seems to require that 3 areas of law be analyzed: (1) the current statutory framework in which the public television system operates;(2) the recent case law in the area of the First Amendment and public broadcasting; and (3) relevant overarching judicial principles. -

Extra-Governmental Censorship in the Advertising Age

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 12 Number 2 Article 5 3-1-1992 Extra-Governmental Censorship in the Advertising Age Steven C. Schechter Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Steven C. Schechter, Extra-Governmental Censorship in the Advertising Age, 12 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 367 (1992). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol12/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXTRA-GOVERNMENTAL CENSORSHIP IN THE ADVERTISING AGE Steven C. Schechter* I. INTRODUCTION "Throughout history, families and religious groups have recognized their influence over the lives of their members and have used this influ- ence to maintain unity and adherence to a given set of values."' Vocal activists have for generations waged wars against works of literature and 2 art that they have found offensive to their religious or moral beliefs. They have attempted to exert their influence over society as a whole and to impose their values over all others. These activists believed that they were providing an invaluable service to society. From the time of the colonization of the United States through the 1950's, moral activists had the weapon of choice on their side: the strong-arm censorship powers of the law and the courts. -

A Southern California Visionary with Northern Michigan Sensibilities

John Lautner By Melissa Matuscak A SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA VISIONARY WITH NORTHERN MICHIGAN SENSIBILITIES 32 | MICHIGAN HISTORY Architect John Lautner would have turned 100 years old on July 16, 2011. Two museums in his hometown of Marquette recently celebrated this milestone with concurrent exhibits. The DeVos Art Museum at Northern Michigan University focused on a professional career that spanned over 50 years and the Marquette Regional History Center told the story of the Lautner family. Combined, they demonstrated how in!uential his family and his U.P. upbringing were to Lautner’s abilities and his eye for design. nyone who has lived in the Upper Peninsula tends to develop a deeper awareness of nature, if only to anticipate the constantly changing weather. !e natural landscapes, and especially Lake Superior, are integral to the way of life in the region in both work and leisure. John Lautner’s idyllic childhood in Marquette stirred what By Melissa Matuscak would become an ongoing quest to create unity between nature and architecture. !e story of what made John Lautner a visionary architect begins with his parents. His father, John Lautner Sr., was born in 1865 near Traverse City, the son of German immigrants. !ough he began school late—at age 15—by age 32 John Sr. had received bachelor’s and master’s degrees in German literature from the University of Michigan. His studies took him to the East Coast and to Europe, but he eventually returned to Michigan to accept a position at Northern State Normal School (now Northern Michigan University) in Marquette in 1903. -

The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art Volume Author/Editor: David W. Galenson Volume Publisher: Cambridge University Press Volume ISBN: 978-0-521-11232-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/gale08-1 Publication Date: October 2009 Title: The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century Author: David W. Galenson URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5785 Chapter 2: The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century Introduction The masters, truth to tell, are judged as much by their influence as by their works. Emile Zola, 18841 Important artists are innovators: they are important because they change the way their successors work. The more widespread, and the more profound, the changes due to the work of any artist, the greater is the importance of that artist. Recognizing the source of artistic importance points to a method of measuring it. Surveys of art history are narratives of the contributions of individual artists. These narratives describe and explain the changes that have occurred over time in artists’ practices. It follows that the importance of an artist can be measured by the attention devoted to his work in these narratives. The most important artists, whose contributions fundamentally change the course of their discipline, cannot be omitted from any such narrative, and their innovations must be analyzed at length; less important artists can either be included or excluded, depending on the length of the specific narrative treatment and the tastes of the author, and if they are included their contributions can be treated more summarily. -

Hegemonic Negotiation in Contemporary Marriage Politics 1

HEGEMONIC NEGOTIATION IN CONTEMPORARY MARRIAGE POLITICS 1 Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non- exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Signature: ________________________________________ __________________ Alysia M.B. Davis Date HEGEMONIC NEGOTIATION IN CONTEMPORARY MARRIAGE POLITICS 2 To Honor and Obey: Hegemonic Negotiation in Contemporary Marriage Politics By Alysia M.B. Davis Doctor of Philosophy Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality __________________________________________ Beth Reingold, Ph.D. Advisor __________________________________________ Martha Albertson Fineman, J.D. Committee Member __________________________________________ Holloway Sparks, Ph.D. Committee Member __________________________________________ Regina Werum, Ph.D. Committee Member Accepted: __________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies ________________ Date HEGEMONIC NEGOTIATION IN CONTEMPORARY MARRIAGE POLITICS 3 To Honor and Obey: Hegemonic Negotiation in Contemporary Marriage Politics By Alysia M.B. Davis M.S., University of Rochester, 2000 Advisor: Beth Reingold Ph.D., University of California at Berkeley An abstract of A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the James T. -

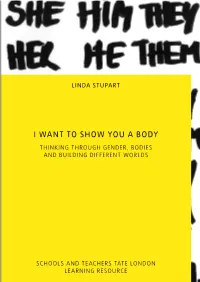

I Want to Show You a Body Thinking Through Gender, Bodies and Building Different Worlds

LINDA STUPART I WANT TO SHOW YOU A BODY THINKING THROUGH GENDER, BODIES AND BUILDING DIFFERENT WORLDS SCHOOLS AND TEACHERS TATE LONDON LEARNING RESOURCE INTRODUCTION Growing up as a gender non-conforming adults) we learn that 53% of respondents child, it was art and being in the art room had self-harmed at some point, of which that was my safe haven. Like other gender 31% had self-harmed weekly and 23% daily. and sexually diverse people, such as lesbian, These and other surveys show that many gay, bisexual and queer people, trans and trans people experience mental distress, gender-questioning people can be made and we know that there is a direct correlation to feel ashamed of who we are, and we between this and our experiences of have to become more resilient to prejudice discrimination and poor understandings in society. Art can help with this. There is of gender diversity. As trans people, we no right and wrong when it comes to art. need to be able to develop resilience and There’s space to experiment. to manage the setbacks that we might Art is where I found my politics; where experience. We need safe spaces to explore I became a feminist. Doing art and learning our feelings about our gender. about art was where I knew that there was Over recent years at Gendered Intelligence another world out there; a more liberal one; we have delivered a range of art-making more radical perhaps; it offered me hope projects for young trans and gender- of a world where I would belong. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE PHILLIPS de PURY & COMPANY ANNOUCES AN EXHIBITION AND BOOK LAUNCH FOR PHOTOGRAPHER GUY BOURDIN IN NEW YORK MARCH 11-25, 2006 New York, February 22, 2006 -- Phillips de Pury & Company is pleased to announce a unique collaboration with Samuel Bourdin, the sole owner of the Guy Bourdin Estate, to represent and exclusively sell photographic prints. Guy Bourdin is considered to be one of the most daring and innovative artists in the world of 20th Century visual culture. A singular artist with the eye of a painter, Bourdin’s compelling and unique body of work has become an inspiration across many creative fields. His groundbreaking legacy represents a turning point in the history of fashion imagery. Simon de Pury, joined by Gerhard Steidl and Pascal Dangin of Steidldangin, is honored to host the launch of the newly published book, Guy Bourdin, A MESSAGE FOR YOU, published by Steidldangin. This two-volume edition was curated and written by Nicolle Meyer, edited by Shelly Verthime and introduced by Alber Elbaz. It focuses on Guy Bourdin's unique collaboration with Nicolle, one of his "mannequins fétiche". All of Volume I images will be exhibited as a series of 75 beautiful color prints, printed and produced by Pascal Dangin. In addition, Volume II images will be presented in the form of a slide projection. The exhibition will open with a book launch and private viewing on March 11th and will be open to the public through March 25th. These works will be shown in the second floor gallery at Phillips de Pury and Company in New York. -

TASCHEN Publishing House Bundles Logistics at Arvato

TASCHEN Publishing House implements new logistics concept together with VVA TASCHEN Publishing House bundles logistics at Sonja Groß Arvato Head of Marketing & Communications Arvato Supply Chain Solutions August 12, 2020 Phone: +49 5241 80-41897 Gütersloh - VVA has won TASCHEN Verlag as a new customer at its [email protected] Gütersloh location. The publishing house is combining the move to the Arvato subsidiary, which began on July 1, 2020, with a reorganization of its international logistics concept. TASCHEN and the VVA are jointly optimizing the international supply chain. The core of the new concept is centralization at a European central warehouse at the Gütersloh location, which will gradually replace the regional warehouses existing in several countries. In the future, all customers in the European markets will be served directly from there. In addition, the publishing house's international sales partners will be linked to the European central warehouse. Until further notice, „KNV Zeitfracht“ will continue to supply the German-speaking book market. "I am very pleased that TASCHEN Publishing House has chosen us for this demanding project," says Stephan Schierke, President VVA. "Outside the usual VVA industry solution, we have worked with TASCHEN to develop tailor-made logistics for the world market. Arvato's cross-industry know-how will be of benefit to us in overcoming the special challenges in terms of logistics and IT". "The new solution will reduce our complexity, lower costs through synergy and economies of scale, and improve our service," said TASCHEN-COO Hans-Peter Kübler. "The prerequisite for such a challenging project is a strong and reliable partner, which we have found in the VVA. -

Nan Goldin and Andres Serrano's Post-Mortem Photography

Visible Care: Nan Goldin and Andres Serrano’s Post-mortem Photography Lauren Jane Summersgill Humanities and Cultural Studies Birkbeck, University of London Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 2 Declaration I certify that this thesis is the result of my own investigations and, except for quotations, all of which have been clearly identified, was written entirely by me. Lauren J. Summersgill October 2014 3 Abstract This thesis investigates artistic post-mortem photography in the context of shifting social relationship with death in the 1980s and 1990s. Analyzing Nan Goldin’s Cookie in Her Casket and Andres Serrano’s The Morgue, I argue that artists engaging in post- mortem photography demonstrate care for the deceased. Further, that demonstrable care in photographing the dead responds to a crisis of the late 1980s and early 1990s in America. At the time, death returned to social and political discourse with the visibility of AIDS and cancer and the euthanasia debates, spurring on photographic engagement with the corpse. Nan Goldin’s 1989 post-mortem portrait of her friend, Cookie in Her Casket, was first presented within The Cookie Portfolio. The memorial portfolio traced the friendship between Cookie and Goldin over fourteen years. The work relies on a personal narrative, framing the works within a familial gaze. I argue that Goldin creates the sense of family to encourage empathy in the viewer for Cookie’s loss. Further, Goldin’s generic and beautified post-mortem image of Cookie is a way of offering Cookie respect and dignity in death. Andres Serrano’s 1992 The Morgue is a series of large-scale cropped, and detailed photographs capturing indiscriminate bodies from within an unidentified morgue. -

NAN GOLDIN Sirens 14 November 2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NAN GOLDIN Sirens 14 November 2019 – 11 January 2020 Marian Goodman Gallery is delighted to announce its first exhibition with Nan Goldin, who joined the gallery in September 2018. This major exhibition – the first solo presentation by the artist in London since the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 2002 – presents an important range of historical works together with three new video works exhibited for the first time. Over the past year Goldin has been working on a significant new digital slideshow titled Memory Lost (2019), recounting a life lived through a lens of drug addiction. This captivating, beautiful and haunting journey unfolds through an assemblage of intimate and personal imagery to offer a poignant reflection on memory and the darkness of addiction. It is one of the most moving, personal and visually arresting narratives of Goldin’s career to date, and is accompanied by an emotionally charged new score commissioned from composer and instrumentalist Mica Levi. Documenting a life at once familiar yet reframed, new archival imagery is cast to portray memory as lived and witnessed experience, yet altered and lost through the effects of drugs. Bearing thematic connections to Memory Lost, another new video work, Sirens (2019), is presented in the same space. This is the first work by Goldin exclusively made from found video footage and is also accompanied by a new score by Mica Levi. Echoing the enchanting call of the Sirens from Greek mythology, who lured sailors to their untimely deaths on rocky shores, this hypnotic work visually and acoustically entrances the viewer into the experience of being high. -

NAN GOLDIN Sirens 14 November 2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NAN GOLDIN Sirens 14 November 2019 – 11 January 2020 Opening reception, Thursday 14 November, 6-8 pm Marian Goodman Gallery is delighted to announce its first exhibition with Nan Goldin, who joined the gallery in September 2018. This major exhibition – the first solo presentation by the artist in London since the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 2002 – will present an important range of historical works together with three new video works exhibited for the first time. Over the past year Goldin has been working on a significant new digital slideshow titled Memory Lost (2019), recounting a life lived through a lens of drug addiction. This captivating, beautiful and haunting journey unfolds through an assemblage of intimate and personal imagery to offer a poignant reflection on memory and the darkness of addiction. It is one of the most moving, personal and visually arresting narratives of Goldin’s career to date, and is accompanied by an emotionally charged new score commissioned from composer and instrumentalist Mica Levi. Documenting a life at once familiar and reframed, new archival imagery is cast to portray memory as lived and witnessed experience, yet altered and lost through the effects of drugs. Bearing thematic connections to Memory Lost, another new video work, Sirens (2019), will be presented in the same space. This is the first work by Goldin exclusively made from found video footage and it will also be accompanied by a new score by Mica Levi. Echoing the enchanting call of the Sirens from Greek mythology, who lured sailors to their untimely deaths on rocky shores, this hypnotic work visually and acoustically entrances the viewer into the experience of being high.