Download The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Naked Bike Ride : Chicago

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE WORLD NAKED BIKE RIDE In the paramount clothes-free event since the dawn of the textile industry, on June 12th Chicagoans will be riding their bikes with the rest of the cycling-world as bare as they dare! This safe, free, natural & non-sexual ride will be leaving at 9 PM from Wicker Park. It will move peacefully through the neighborhoods of Chicago spreading fun, trust and love. Hundreds of people have already signed up for the ride, butt other rides hosted simultaneously in 22 other cities worldwide (including Vancouver, London, San Francisco, & Montreal) will make this event the worlds largest naked bike ride in history. The message we are bringing is one of simplification and respect. The naked body is the common experience of all people, all of the time. It is the page we use to write our stories of life and death with. For a future to exist for tomorrow’s generations, we pledge to stop wasting the energy of the Earth, stop fighting wars in the name of that waste, and come to love all of humanity as one. The World Naked Bike Ride is being organized democratically through on-line discussion groups. It is operated locally through the grassroots work of regular people who believe in changing the world through peace, love and conviction for a sustainable world. The World Naked Bike Ride is endorsed by the following groups: Artists For Peace Body Freedom Collaboration. The Work Less Party The Nude Garden Party Car Busters International Naturist Association Shake Chicago D&D Mugs Chicago Bicycle Federation & Chicago’s Critical Mass! For more information on the background leading up to this event and for contact information of local participants, please visit www.WorldNakedBikeRide.org and www.WorldNakedBikeRide.org/chicago . -

GLOSSÁRIO DO NATURISMO (Atualização Permanente)

GLOSSÁRIO DO NATURISMO (Atualização Permanente) A AANR-(American Association for Nude Recreation) Associação Americana para Recreação Nudista). Entidade norte-americana de Naturismo. AAPP-Associação de Amigos da Praia do Pinho. Pioneira, fundada em 1986. Federada da FBrN, possui um sítio eletrônico para divulgação de suas atividades. Ver PINHO. ABRICÓ-Praia de Naturismo do Rio de Janeiro, mantida pela ANA, considerada um dos principais redutos do Naturismo no Brasil. ADAMISMO-No Dicionário Houaiss da língua portuguesa consta como “seita herética cujos adeptos compareciam nus às assembléias, para imitar a inocência de Adão antes do pecado original, e que, depois de seu surgimento, no séc. II ressurgiu na Boêmia no séc. XV. No Aurélio não se encontra menção à palavra Adamismo, mas só Adamita: membro de uma seita religiosa herética do séc. II, cujos adeptos compareciam às assembléias despidos para imitar o estado de inocência de Adão antes do pecado, e que ressuscitou no séc. XV entre os tchecos. Sinônimo romântico para os termos Naturismo/Nudismo. (RF/JB) ADAMITAS DE PRODICUS-Seita cujos membros eram acusados de viverem nus e que designou durante toda a Idade Média os partidários do retorno ao estado original do homem antes do “pecado”. ADÃO-Andava nu no Paraíso, até ser expulso... ADEGAS, Praia das- Praia de Naturismo oficializada de Portugal. ADOLF HITLER-Ditador na Alemanha. Ilegalizou e mandou fechar os inúmeros centros naturistas alemães durante o regime nazista. ADRIANO JORGE-Famoso médico amazonense da primeira metade do século XX. Simpático às causas do nudismo/naturismo, segundo informações do poeta Luis Bacellar chegava a atender nu aos seus pacientes. -

BBC Learning English Weekender World Naked Bike Ride

BBC Learning English Weekender World Naked Bike Ride Jackie: Hello, I'm Jackie Dalton and you're listening to Weekender with bbclearningenglish.com. Do you enjoy cycling, taking your bike out and getting some exercise or fresh air? What about cycling with absolutely no clothes on? Well, I've never tried it myself, but hundreds of people all over the world have, and they think it's lots of fun. This weekend, the World Naked Bike Ride takes place. People in cities from Vancouver to London will be getting out their bicycles and taking off their clothes. The question is: why? Conrad Schmidt is the man who's linking up cyclist groups from around the World for this event. He spoke to me over the telephone from Vancouver and he's going to give us some answers. What reasons does he give for the naked bike ride? Conrad It's about getting a message out there that cycling is good for people and it's good for the planet and that if we're going to be sustainable, we've got to think about other things besides car culture. And just making a happier, healthier planet. Jackie: Well, Conrad said cycling is good for people and good for the planet. He uses the word sustainable – a word we often hear in connection with the environment. It means to do things without causing damage to the environment. A nice phrase he also used was 'getting the message out there', which means making sure people know, or you could also say 'making people more aware' – Weekender © BBC Learning English Page 1 of 3 bbclearningenglish.com 'aware' – a word that Conrad will use next when talking about climate change. -

Photos: As Temperatures Heat Up, Tripadvisor Bares All Revealing Top 5 Naked Events and Top 5 Nude Beaches

Photos: As Temperatures Heat Up, TripAdvisor Bares All Revealing Top 5 Naked Events and Top 5 Nude Beaches NEWTON, Mass., July 23 /PRNewswire/ -- In honor of the recent Nude Recreation Week, TripAdvisor is bringing opportunities to go "au naturel" out into the light, from a massive skinny-dip to relaxing sans suit on sunny shores. TripAdvisor®, the world's most popular and largest travel community, today announced the top 5 naked events and top 5 nude beaches according to TripAdvisor editors and travelers. To view the Multimedia News Release, go to: http://www.prnewswire.com/mnr/tripadvisor/37969/ (Photo: http://www.newscom.com/cgi-bin/prnh/20090723/NY50768 ) (Logo: http://www.newscom.com/cgi-bin/prnh/20080902/TRIPADVISORLOGO ) Top 5 Naked Events: As these five events prove, nudity is truly a way to express oneself. Biking in the Buff: World Naked Bike Ride - Worldwide, June and July Each year since 2004, bike riders have joined to celebrate cycling and protest a culture where cars are king. This year, in 20 countries around the world, participants advocated freedom from oil. .and fabric. Nude cyclists bared their bods to stand (or rather sit) for what they believe in, with messages painted on their backs, fronts, and rears. If you plan to participate next year, one TripAdvisor traveler advises, "Remember the sunscreen. .those saddles will be hot, hot, hot, so cover them up before alighting, people!" Daring Dip: AANR World Record Skinny Dip - Across North America, July 2009 Put more than 12,000 people shoulder deep in pools across North America without a stitch of clothing in sight, and what do you get? The "largest number of people skinny dipping at once," now a category in the Guinness Book of World Records thanks to the American Association for Nude Recreation. -

Diary of a Nudist: the Daily Newds 1/10/08 Page 1 of 10

Diary of a Nudist: The Daily Newds 1/10/08 Page 1 of 10 SEARCH BLOG FLAG BLOG Next Blog» Create Blog | Sign In Diary of a Nudist Nude, we resemble one another... THURSDAY, JANUARY 10, 2008 E-Mail Nudiarist The Daily Newds 1/10/08 Got a tip or a comment? Please send e-mail to [email protected]. About Me Nudiarist View my complete profile Advertisement Search Amazon.… z Hookers for Jesus are bringing Christianity to the Adult Entertainment Expo in Las Vegas this week. [The Christian Post] z The new Canadian television drama MVP is drawing complaints for being too "smutty'. http://nudiarist.blogspot.com/2008/01/daily-newds-11008.html 1/10/2008 Diary of a Nudist: The Daily Newds 1/10/08 Page 2 of 10 Eat, Pray, Lov… "When it's appropriate to the story, you will see bare Elizabeth Gilbert (… $8.25 bums and you . may see the odd nipple, but it's not gratuitous." [The London Free Press] Noel z A new bill being introduced in Florida attempts to Josh Groban (Aud… redefine "indecent exposure". $9.99 Senator Gary Siplin's bill calls for a warning and phone call Kingston 2GB … to parents the first time a student exposes his or her Kingston H. Corp… sexual organs, even if covered by underwear, in a vulgar $14.99 or indecent manner. [cbs4.com] z "Naked News" can now be seen in 172 nations. [Broadcaster] Planet Earth - … David Attenborou… z Peek a Boob is not the the name of some adult game, it's a $54.99 breastfeeding solution for shy nursing mothers. -

Administering Justice Beyond Cinderella

THE GRISTLE, P.06 + FILM SHORTS, P.23 + BY THE SHORE,,P.30 c a s c a d i a PICKFORD CALENDAR INSIDE REPORTING FROM THE HEART OF CASCADIA WHATCOM SKAGIT ISLAND COUNTIES 05-30-2018* • ISSUE:*22 • V.13 Hiking Washington's Fire Lookouts, TRAIL TIME P.14 ADMINISTERING JUSTICE Inside the prosecutors race P.08 FIREFLY LOUNGE: BEYOND Opening up our entertainment CINDERELLA vistas, P.18 Fun with fairy tales P.15 A brief overview of this 30 FOOD THISWEEK week’s happenings 24 WEDNESDAY [05.30.18] DANCE Bellingham Scottish Gathering: 9am-6pm, Hov- ONSTAGE ander Homestead Park, Ferndale B-BOARD Junie B. Jones: 6:30pm, Lincoln Theatre, Mount Capstone Concert: 2pm and 7:30pm, Performing Vernon Arts Center, WWU Way North Comedy: 7pm, Culture Cafe Cinderella: 7:30pm, Mount Baker Theatre 23 MUSIC MUSIC FILM Classical on Tap: 7pm, Chuckanut Brewery Fidalgo Youth Symphony: 1pm, McIntyre Hall Brad Shigeta Quartet: 7pm, Sylvia Center for the Arts Traditional Jazz: 2-5pm, VFW Hall Bayshore Symphony: 7:30pm, St. Paul’s Episcopal 18 THURSDAY [05.31.18] Church, Mount Vernon MUSIC ONSTAGE COMMUNITY Junie B. Jones: 6:30pm, Lincoln Theatre, Mount Blast from the Past: Through Sunday, throughout 16 Vernon Sedro-Woolley The Wolves: 7:30pm, Firehouse Performing Arts Center Farmers’ Day Parade: 10:30am, downtown Lynden ART The Aliens: 7:30pm, Lucas Hicks Theater Skits and Sketches: 7:30pm, Black Box Theatre, WCC GET OUT 15 Good, Bad, Ugly: 8pm, Upfront Theatre Girls on the Run: 9am, Lake Padden The Project: 10pm, Upfront Theatre Doxie Walk: 10am, Fairhaven Train Station STAGE Splash Dash Color Run: 10am, Little Mountain MUSIC Elementary, Mount Vernon MVHS Finale Concert: 7pm, McIntyre Hall, Mount Beach Fest & Feast: 11am-3pm, Birch Bay State Park 14 Vernon Ride to the Border: 11am-5pm, downtown Blaine Zombies Versus Survivors: 12pm, Maritime Heri- WORDS tage Park GET OUT The Green Reaper: 7pm, Village Books FOOD [06. -

World Naked Bike Ride Day a Seasonal Lesson Plan by Shannon Felt

A Wild Ride in Portland: World Naked Bike Ride Day A Seasonal Lesson Plan by Shannon Felt www.TeachingHouse.com Teacher’s Notes & Answer Key Level Upper Intermediate + Lesson Aims Learners will practice reading for gist and detail and will practice discerning the meaning of new vocab from context. Approximate 45-60 minutes Timing Notes to the World Naked Bike Ride (WNBR) Day is really more of an event than a holiday. teacher The official date varies as different rides take place on different days around the world, but it generally occurs in June or July. This lesson focuses on the event in Portland as it claims to be the largest. It supposedly began in 2004 and has been growing each year. The official motto is “bare as you dare,” which means that while nudity is encouraged, it is not mandatory. The goal of the holiday also varies slightly according to the event, but the Portland maintains that it’s mainly to raise awareness about dependence on fossil fuels and encourage positive body image. The article used in this lesson focuses partially on the Portland World Naked Bike Ride overall and also on the author’s feelings about participating for the first time. The article is from The Atlantic so the language is a bit advanced. I’ve adapted it slightly, though mainly just by cutting out a few paragraphs for the sake of length. A caution: since this lesson does center around the idea of public nudity, some students could be uncomfortable/offended (there are a few bare backsides in the picture connected to the article which could be removed or covered). -

Dsr-Newsletter-11-23-2020-Sfw.Pdf

September 28, 2020 Volume 20, Issue 14 Weekly Newsletter WE WISH YOU COVID-19 Update A HAPPY We are now well into fall and with that we are seeing much cooler temperatures. As it AND SAFE gets cooler the Coronavirus numbers have been rising in San Diego. Due to this in- crease the governor of California has adjusted our restriction level to purple. How is THANKSGIVING this effecting business here at DeAnza Springs Resort, you ask? In an effort to do our part as a business to protect our residents, members and guests we must return to take out orders only from the café and lounge, we will continue to require the use of a face covering while in the clubhouse and we will not be hosting any organized group Inside this issue activities. COVID-19 Update ....................... 2 We are very thankful that we are still open. There is still plenty for you to do if you Clothes free creatives guild ........ 2 wish to pay us a visit. Nude relaxation and recreation are what we are here for and with the temps in the 70’s during the day you can always find a great spot to relax Recreational Naturism ............... 3 naturally. Though the recreation in groups is limited we still have some of the best Nudism vs Naturism.................... 3 hiking in southern California and the best part is you will be able to hike without en- Writing from Naturist Life ........... 4 countering very many other people. We do look forward to seeing you very soon. Grin and bare it .......................... -

Do Bom Uso Do Mau Gênero

cadernos pagu (44), janeiro-junho de 2015:171-198. ISSN 1809-4449 DOSSIER: DIGITAL PATHS: BODIES, DESIRES, VISIBILITIES Self-exposed nudity on the net: Displacements of obscenity and beauty?* Paula Sibilia** Resumo This article focuses on images of nude female bodies that circulate today within the media, and on the internet in particular. Prime attention is given to the images that women publish as self portraits. From a genealogical perspective, we examine the politicization involved in a new set of practices, diverse but recent, and how they impact on current redefinitions of beauty standards and criteria defining what is considered to be obscene. Palavras-chave: Body, Subjectivity, Nudity, Obscenity, Internet. * Received January 31, 2015, approved March 24, 2015. Translated by Miriam Adelman. Reviewed by Richard Miskolci. ** Professor in the Graduate Program in Communication (PPGCOM) and the Department of Media and Cultural Studies of the UFF, Niteroi, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. [email protected] http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1809-4449201500440171 172 Self-exposed nudity on the net Over the last few decades, the boundaries around what kinds of images can be legitimately shown in public have been redrawn, particularly where sexuality and women’s naked bodies are concerned (Sibilia, 2008). Increasingly distant from the typical 19th and 20th centuries forms of modesty and including fields that range from advertising and video clips to the visual and performing arts and the self-portraits that multiply through the social networks of the web, showing naked bodies seems to be the latest fashion. Furthermore, a wide range of women are taking up a certain kind of activism spurred by the younger generations, exhibiting their nudity in the name of a multiplicity of “noble” causes, whether ecology, reproductive rights, freedom of expression or respect for cultural difference. -

AANR-West Hosts Annual Summer Festival at Glen Eden

June 2021 Vol 5 No 6 between clubs, and the calendar for future nude 5K running Western Region News events. It was a diverse collection of interests! From our table, we handed out iron-on patches, temp tattoos, and commemorative pins to celebrate AANR’s 90th Anniversary. We also handed out some free writing pens, emery boards, SPF lip balm, and wrist bands that turn blue if one is in the sun too long. Those people who had not heard of the AANR-West Passport program said they were eager to visit many of the clubs in the region as soon as the pandemic restrictions were lifted. We also handed out copies of our monthly Western Sun newsletter. Last, we also sold several of our GPS T-Shirts. In the afternoon, GE opened a beer and wine bar near our booth and that helped attract more visitors our way. They also had Gary Mussell, Judy T, and Larry Gould share the AANR-West information booth Broadway Joe & Anita provide background music in the pool at Glen Eden. area. AANR-West Hosts Annual Games and the Raffle In the late morning, we organized a couple of competitive Summer Festival at Glen Eden games on the lawn above the pool. The most popular was the By Gary Mussell “Frisbee toss for Accuracy” when contestants had to fling a Frisbee across the lawn to try to land it inside a hula hoop. It The annual Summer Festival, held this year at the Glen Eden was much harder and than it sounds! The top three winners won Sun Club in California, was held in conjunction with the club’s AANR towels. -

Nudist Groups to Support Nude Bike Ride Through L.A

AFFILIATED NATIONALLY WITH JUNE 2012 SERVING THE NATURIST COMMINUTY FOR OVER TEN YEARS VOL. 11 NO 6 NUDIST GROUPS TO SUPPORT NUDE BIKE RIDE THROUGH L.A. ON JUNE 16 SCNA EVENTS IN JUNE 2012 SCNA is joining forces with the local YNA (Youth Naturists of Saturday, June 9 America) club and also with ANFA (American Naturist Families Pool Party, Brentwood Association, based in Long Beach) to support and help organize Friday-Sunday, June 8-10 the World Naked Bike Ride event schedule for downtown Los Angeles on June 16. AANR Summer Festival Glen Eden, Corona Saturday, June 16 Last year, the event was hosted by couple of non-nudists who Nude Bike Ride thru LA wanted to promote bike safety. They decided not to be the organizers this year, so our 3 groups have stepped in. Saturday-Sunday, June 23-24 Deep Creek Hike San Bernardino Mtns (3-club event) The police permit is for a bike Saturday June 30 ride starting in Silverlake, Independence Day Parade/ $2 Bill Day Carpinteria snaking through downtown Los Angeles and back again. Monthly Meet-up Dinner Meetings Tuesday, June 12, 6:45 – 8:30 PM, Van Nuys Last year, over 250 riders Thursday, June 21, 6:45 – 8:30 PM, West LA participated in the event on the same route. Because it was a Friday, June 8, 6:45 – 8:30 PM, Ventura “freedom of speech protest” Monday, June 18, 6:45 – 8:30 PM, Pasadena against the U.S. dependency Wednesday, June 27, 6:45 – 8:30 PM, Torrance on oil and also to promote Naked Yoga bicycle safety, LAPD allowed Indefinitely postponed, Culver City the riders to be nude and, in SCNA EVENTS IN JULY 2012 fact, they gave the riders an Saturday, July 7, Noon-8pm escort through downtown! SCNA joins Olympian Club at GE for picnic If you do not want to go nude Saturday , July 14, Noon – whenever or top-free, another idea is to Deer Park Olympics, Body Painting Contest, Toga! apply body paint before the Sunday July 22, Noon – 7pm race to cover "private" areas. -

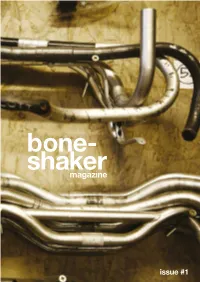

Bone- Shakermagazine

bone- shakermagazine issue #1 Boneshaker: Real Cycling Except this isn’t real, of course, it’s digital. To get your hands on a real Boneshaker, to feel it and smell it and hide it in your pannier, go here. We make other great bike stuff too, especially bicycle art prints. Check them out here. And to let your ears take your mind on a journey, there’s our new podcast series. boneshakermag.wordpress.com [email protected] © Adam Faraday © Adam Since helping to set up and run Bristol, UK – where there is a a community bike project here steady-growing, vibrant bicycle in Bristol, my eyes have been culture – to further afield and opened to the breadth of people around the globe. It is my hope and projects around the world that the following pages will doing great great things with both inspire and entertain, raise bicycles. And what impresses awareness and bring a smile to me most about the vast majority your face... and appeal to both of these is the humanity and bike-heads and to those who may desire to do things for the greater not yet even have experienced good that almost always seem to the true joy and freedom that can be an integral part of them. be found from our two-wheeled friends. Thanks for reading. Boneshaker is an attempt to bring together some of these people and projects, both on a local level James Lucas starting with my hometown of www.thebristolbikeproject.org Contents Contents Puncture Kit 4 My Beautiful Bike 8 Mini Bike Winter Olympics VII 10 Jake’s Bikes 12 Serai 20 Spoke‘n’chain 22 ‘Tunnel’ 30 Slowcoast Soundslides 32 Tour of Switzerland 1966 36 The Bicycle Quick Release: Let ‘em have it 38 Bicycology My Beautiful Bike.