Classification of the Grasslands, Shrublands, Woodlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 2000 Volume 19, No. 1

March 2000 Volume 19, No. 1 In this issue: WNPS News . 2 Botany Briefs Arabis pusilla Dropped from Candidate List . 2 C.L. Porter . 2 New Research Natural Areas . 3 Revolutionary New Taxonomy . 3 On the Germination and Viability of Yermo xanthocephalus akenes . 4 Noteworthy Discoveries . 7 Quotes (John C. Fremont) . 8 Bighorn Native Plant Society . 8 Moonwort (Botrychium lunaria) is one of nearly a dozen species of Botrychium known or reported for Wyoming. It can be recognized by its overlapping, fan-shaped fleshy leaflets and bead- like fertile leaf segments. In Wyoming, moonwort is uncommonly seen in moist meadows forest edges, and alpine scree slopes in the Absaroka, Gros Ventre, Wind River, Bighorn, and Medicine Bow ranges. Moonworts were a specialty of the late Dr. Warren “Herb” Wagner of the University of Michigan, who described 13 of the 30 taxa recognized in the 1993 treatment of the genus in the Flora of North America. Wagner was also famous for unraveling many of the intricacies of hybridization and reticulate evolution in Asplenium and other plants and for conceptual advances in systematics, such as the “Wagner Groundplan- Divergence” method of assessing phylogenetic relationships. Wagner passed away in January at the age of 79. Illustration by Walter Fertig. WNPS NEWS We’re looking for new members: Do you know someone who would be interested in joining WNPS? Scholarship Winners: The WNPS Board is pleased to Send their name or encourage them to contact the announce that three University of Wyoming botany Society for a complimentary newsletter. graduate students have been awarded scholarships for the 1999-2000 academic year. -

Lundberg Et Al. 2009

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 51 (2009) 269–280 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Allopolyploidy in Fragariinae (Rosaceae): Comparing four DNA sequence regions, with comments on classification Magnus Lundberg a,*, Mats Töpel b, Bente Eriksen b, Johan A.A. Nylander a, Torsten Eriksson a,c a Department of Botany, Stockholm University, SE-10691, Stockholm, Sweden b Department of Environmental Sciences, Gothenburg University, Box 461, SE-40530, Göteborg, Sweden c Bergius Foundation, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, SE-10405, Stockholm, Sweden article info abstract Article history: Potential events of allopolyploidy may be indicated by incongruences between separate phylogenies Received 23 June 2008 based on plastid and nuclear gene sequences. We sequenced two plastid regions and two nuclear ribo- Revised 25 February 2009 somal regions for 34 ingroup taxa in Fragariinae (Rosaceae), and six outgroup taxa. We found five well Accepted 26 February 2009 supported incongruences that might indicate allopolyploidy events. The incongruences involved Aphanes Available online 5 March 2009 arvensis, Potentilla miyabei, Potentilla cuneata, Fragaria vesca/moschata, and the Drymocallis clade. We eval- uated the strength of conflict and conclude that allopolyploidy may be hypothesised in the four first Keywords: cases. Phylogenies were estimated using Bayesian inference and analyses were evaluated using conver- Allopolyploidy gence diagnostics. Taxonomic implications are discussed for genera such as Alchemilla, Sibbaldianthe, Cha- Fragariinae Incongruence maerhodos, Drymocallis and Fragaria, and for the monospecific Sibbaldiopsis and Potaninia that are nested Molecular phylogeny inside other genera. Two orphan Potentilla species, P. miyabei and P. cuneata are placed in Fragariinae. -

Vascular Plants and a Brief History of the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands

United States Department of Agriculture Vascular Plants and a Brief Forest Service Rocky Mountain History of the Kiowa and Rita Research Station General Technical Report Blanca National Grasslands RMRS-GTR-233 December 2009 Donald L. Hazlett, Michael H. Schiebout, and Paulette L. Ford Hazlett, Donald L.; Schiebout, Michael H.; and Ford, Paulette L. 2009. Vascular plants and a brief history of the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS- GTR-233. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 44 p. Abstract Administered by the USDA Forest Service, the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands occupy 230,000 acres of public land extending from northeastern New Mexico into the panhandles of Oklahoma and Texas. A mosaic of topographic features including canyons, plateaus, rolling grasslands and outcrops supports a diverse flora. Eight hundred twenty six (826) species of vascular plant species representing 81 plant families are known to occur on or near these public lands. This report includes a history of the area; ethnobotanical information; an introductory overview of the area including its climate, geology, vegetation, habitats, fauna, and ecological history; and a plant survey and information about the rare, poisonous, and exotic species from the area. A vascular plant checklist of 816 vascular plant taxa in the appendix includes scientific and common names, habitat types, and general distribution data for each species. This list is based on extensive plant collections and available herbarium collections. Authors Donald L. Hazlett is an ethnobotanist, Director of New World Plants and People consulting, and a research associate at the Denver Botanic Gardens, Denver, CO. -

Mountain Plants of Northeastern Utah

MOUNTAIN PLANTS OF NORTHEASTERN UTAH Original booklet and drawings by Berniece A. Andersen and Arthur H. Holmgren Revised May 1996 HG 506 FOREWORD In the original printing, the purpose of this manual was to serve as a guide for students, amateur botanists and anyone interested in the wildflowers of a rather limited geographic area. The intent was to depict and describe over 400 common, conspicuous or beautiful species. In this revision we have tried to maintain the intent and integrity of the original. Scientific names have been updated in accordance with changes in taxonomic thought since the time of the first printing. Some changes have been incorporated in order to make the manual more user-friendly for the beginner. The species are now organized primarily by floral color. We hope that these changes serve to enhance the enjoyment and usefulness of this long-popular manual. We would also like to thank Larry A. Rupp, Extension Horticulture Specialist, for critical review of the draft and for the cover photo. Linda Allen, Assistant Curator, Intermountain Herbarium Donna H. Falkenborg, Extension Editor Utah State University Extension is an affirmative action/equal employment opportunity employer and educational organization. We offer our programs to persons regardless of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age or disability. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Robert L. Gilliland, Vice-President and Director, Cooperative Extension -

Shoshonea Pulvinata Evert & Constance (Shoshone Carrot): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Shoshonea pulvinata Evert & Constance (Shoshone carrot): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project January 28, 2005 Jennifer C. Lyman, Ph.D. Garcia and Associates 7550 Shedhorn Drive Bozeman, MT 59718 Peer Review Administered by Center for Plant Conservation Lyman, J.C. (2005, January 28). Shoshonea pulvinata Evert & Constance (Shoshone carrot): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/ projects/scp/assessments/shoshoneapulvinata.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people helped with the preparation of this technical conservation assessment. Kent Houston, Shoshone National Forest, provided historical information about species surveys and about individuals who contributed to our knowledge of Shoshonea pulvinata. Tessa Dutcher and Bonnie Heidel of the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database both helped to make files and reports available. Erwin Evert and Robert Dorn also discussed their considerable field and herbarium studies, as well as their ideas about future conservation needs. Laura Bell of The Nature Conservancy’s Heart Mountain Reserve also shared her knowledge about S. pulvinata at that site, and discussed future conservation needs there. AUTHOR’S BIOGRAPHY Jennifer C. Lyman received her Ph.D. in Plant Ecology and Genetics from the University of California, Riverside. Her thesis focused on an ecological and genetic comparison of the endemic plant Oxytheca emarginata (Polygonaceae), restricted to the San Jacinto Mountains of California, with a few of its widespread congeners. After completion of her doctorate, she became a biology professor at Rocky Mountain College in Billings, MT in 1989. In 1991, Dr. -

Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora, Bryce

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora Bryce Canyon National Park Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR–2009/153 ON THE COVER Matted prickly-phlox (Leptodactylon caespitosum), Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah. Photograph by Walter Fertig. Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora Bryce Canyon National Park Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR–2009/153 Author Walter Fertig Moenave Botanical Consulting 1117 W. Grand Canyon Dr. Kanab, UT 84741 Sarah Topp Northern Colorado Plateau Network P.O. Box 848 Moab, UT 84532 Editing and Design Alice Wondrak Biel Northern Colorado Plateau Network P.O. Box 848 Moab, UT 84532 January 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientifi c community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifi cally credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. The Natural Resource Technical Report series is used to disseminate the peer-reviewed results of scientifi c studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service’s mission. The reports provide contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. -

Summer 2009 33(2).Qxd

Aquilegia Newsletter of the Colorado Native Plant Society “. dedicated to the appreciation and conservation of the Colorado native flora” Carex Workshop and Field Trip with Dr. Tony Reznicek by Pamela Smith (President), Northern Chapter separating Colorado carices into groupings that greatly simplifies field identification. The handout is available from Leo P. Last summer, Dr. Anton A. (Tony) Reznicek led two days of Bruederle, who organized this event. This information also helps workshops which, coupled with a daylong field trip, provided tips one to focus on particular characteristics of each species. In the for field identification of sedges, specifically those in the oft- field, we learned additional pointers and characters for identifying intimidating genus Carex. Dr. Reznicek serves as the Assistant over 20 species of Colorado sedges that are included in this report. Director, Research Scientist, and Curator of the University of A highlight of the field trip was finding a species that is new Michigan Herbarium in Ann Arbor. to Colorado. Carex conoidea is largely an eastern species, extend- The workshops, which were presented on consecutive days at ing west to Minnesota, Iowa, and Missouri, with disjunct popula- the UC Denver Downtown Campus, included a slide presentation tions in Arizona, New Mexico, and now Colorado. However, it is on the sedge family (Cyperaceae), including the evolutionary his- never common and is listed as state threatened or endangered in tory of the perigynium, a distinctive and unusual structure that is five eastern states (USDA PLANTS Database). diagnostic for the genus Carex (Note: Kobresia in our flora has a With approximately 2,000 species of Carex in the world, this similar structure.). -

List of Plants for Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve Plant Checklist DRAFT as of 29 November 2005 FERNS AND FERN ALLIES Equisetaceae (Horsetail Family) Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum arvense Present in Park Rare Native Field horsetail Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum laevigatum Present in Park Unknown Native Scouring-rush Polypodiaceae (Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Cystopteris fragilis Present in Park Uncommon Native Brittle bladderfern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Woodsia oregana Present in Park Uncommon Native Oregon woodsia Pteridaceae (Maidenhair Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Argyrochosma fendleri Present in Park Unknown Native Zigzag fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cheilanthes feei Present in Park Uncommon Native Slender lip fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cryptogramma acrostichoides Present in Park Unknown Native American rockbrake Selaginellaceae (Spikemoss Family) Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella densa Present in Park Rare Native Lesser spikemoss Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella weatherbiana Present in Park Unknown Native Weatherby's clubmoss CONIFERS Cupressaceae (Cypress family) Vascular Plant Pinales Cupressaceae Juniperus scopulorum Present in Park Unknown Native Rocky Mountain juniper Pinaceae (Pine Family) Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies concolor var. concolor Present in Park Rare Native White fir Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies lasiocarpa Present -

Hare-Footed Locoweed,Oxytropis Lagopus

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Hare-footed Locoweed Oxytropis lagopus in Canada THREATENED 2014 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2014. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Hare-footed Locoweed Oxytropis lagopus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xi + 61 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 1995. COSEWIC status report on the Hare-footed Locoweed Oxytropis lagopus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 24 pp. Smith, Bonnie. 1995. COSEWIC status report on the Hare-footed Locoweed Oxytropis lagopus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 24 pp. Production note: C COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Juanita Ladyman for writing the status report on the Hare-footed Locoweed (Oxytropis lagopus) in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Bruce Bennett, Co-chair of the Vascular Plant Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur L’oxytrope patte-de-lièvre (Oxytropis lagopus) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Hare-footed Locoweed — Photo credit: Cheryl Bradley (with permission). Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2014. -

Nectar Flower Use and Electivity by Butterflies in Sub-Alpine Meadows

138138 JOURNAL OF THE LEPIDOPTERISTS’ SOCIETY Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 62(3), 2008, 138–142 NECTAR FLOWER USE AND ELECTIVITY BY BUTTERFLIES IN SUB-ALPINE MEADOWS MAYA EZZEDDINE AND STEPHEN F. M ATTER Department of Biological Sciences and Center for Environmental Studies, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati OH 45221-0006; email: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Nectar flowers are an important resource for most adult butterflies. Nectar flower electivity was evaluated for the pierid butterflies Pontia occidentalis (Reak.), Colias nastes Bdv., Colias christina Edw., Colias meadii Edw., Colias philodice Godt., and Pieris rapae (L.), and the nymphalid Nymphalis milberti (Godt.). Butterflies were observed in a series of sub-alpine meadows in Kananaskis Country, Alberta, Canada. A total of 214 observations of nectar feeding were made over four years. The butterflies were found to nectar on a range of species of flowering plants. Despite the variety of flower species used, there was relative consis- tency in use among butterfly species. Tufted fleabane (Erigeron caespitosus Nutt.) and false dandelion (Agoseris glauca (Pursh) Raf.) were the flowers most frequently elected by these butterflies. Additional key words: Alpine, habitat quality, preference, Pieridae, Nymphalidae, host plants, Kananaskis Country, Alberta INTRODUCTION resource is particularly valuable having appropriate For most species of butterflies, nectar is the main viscosity, sugar content, amino acids or other nutrients. source of food energy in the adult stage. Access to Alternatively, an elected resource may simply be nectar resources can affect many aspects of the ecology enticing without offering any substantial or consistent of butterflies. For example, flowers have been shown to benefit. -

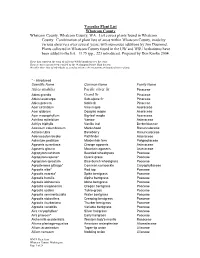

Vascular Plant List Whatcom County Whatcom County. Whatcom County, WA

Vascular Plant List Whatcom County Whatcom County. Whatcom County, WA. List covers plants found in Whatcom County. Combination of plant lists of areas within Whatcom County, made by various observers over several years, with numerous additions by Jim Duemmel. Plants collected in Whatcom County found in the UW and WSU herbariums have been added to the list. 1175 spp., 223 introduced. Prepared by Don Knoke 2004. These lists represent the work of different WNPS members over the years. Their accuracy has not been verified by the Washington Native Plant Society. We offer these lists to individuals as a tool to enhance the enjoyment and study of native plants. * - Introduced Scientific Name Common Name Family Name Abies amabilis Pacific silver fir Pinaceae Abies grandis Grand fir Pinaceae Abies lasiocarpa Sub-alpine fir Pinaceae Abies procera Noble fir Pinaceae Acer circinatum Vine maple Aceraceae Acer glabrum Douglas maple Aceraceae Acer macrophyllum Big-leaf maple Aceraceae Achillea millefolium Yarrow Asteraceae Achlys triphylla Vanilla leaf Berberidaceae Aconitum columbianum Monkshood Ranunculaceae Actaea rubra Baneberry Ranunculaceae Adenocaulon bicolor Pathfinder Asteraceae Adiantum pedatum Maidenhair fern Polypodiaceae Agoseris aurantiaca Orange agoseris Asteraceae Agoseris glauca Mountain agoseris Asteraceae Agropyron caninum Bearded wheatgrass Poaceae Agropyron repens* Quack grass Poaceae Agropyron spicatum Blue-bunch wheatgrass Poaceae Agrostemma githago* Common corncockle Caryophyllaceae Agrostis alba* Red top Poaceae Agrostis exarata* -

Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora, Cedar Breaks National

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora Cedar Breaks National Monument Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR—2009/173 ON THE COVER Peterson’s campion (Silene petersonii), Cedar Breaks National Monument, Utah. Photograph by Walter Fertig. Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora Cedar Breaks National Monument Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR—2009/173 Author Walter Fertig Moenave Botanical Consulting 1117 W. Grand Canyon Dr. Kanab, UT 84741 Editing and Design Alice Wondrak Biel Northern Colorado Plateau Network P.O. Box 848 Moab, UT 84532 February 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientifi c community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifi cally credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. The Natural Resource Technical Report series is used to disseminate the peer-reviewed results of scientifi c studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service’s mission. The reports provide contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. Current examples of such reports include the results of research that addresses natural resource management issues; natural resource inventory and monitoring activities; resource assessment reports; scientifi c literature reviews; and peer- reviewed proceedings of technical workshops, conferences, or symposia.