Systematics and Polyploid Evolution in Potentilleae (Rosaceae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pharmacognostical Identification of Alchemilla Japonica Nakai Et Hara

© 2015 Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmacognosy Research, 3 (3), 59-68 ISSN 0719-4250 http://jppres.com/jppres Original Article | Artículo Original Pharmacognostical identification of Alchemilla japonica Nakai et Hara [Identificación farmacognóstica de Alchemilla japonica Nakai et Hara] Yun Zhu, Ningjing Zhang, Peng Li* School of Pharmacy, Shihezi University/Key Laboratory of Phytomedicine Resources & Modernization of TCM, Shihezi Xinjiang 832002, PR China. * E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Resumen Context: Alchemilla japonica is a therapeutically important medicinal Contexto: Alchemilla japonica es una planta medicinal, terapéutica- plant, which is widely used in traditional medicine external application mente importante, que se utiliza ampliamente en la medicina tradicional for injuries as well as orally for acute diarrhea, dysmenorrhea, and por aplicación externa en lesiones, así como por vía oral para la diarrea menorrhagia, among others. However, there is not a correct identification aguda, dismenorrea y menorragia, entre otras. Sin embargo, no hay una of this species and is of prime importance differentiate it from commonly correcta identificación de la especie y es de primordial importancia available adulterants or substitutes, in fresh, dried or powdered state. diferenciar esta de adulterantes comúnmente disponibles o sustitutos, en There is only a small number of data of pharmacological standards for estado fresco, seco o en polvo. Sólo hay un pequeño número de datos de identification and authentication of A. japonica. patrones farmacológicos para la identificación y autenticación de A. Aims: To characterize morpho-anatomically the roots, leaves and stems japonica. of Alchemilla japonica Nakai et Hara (Rosaceae), explore and establish the Objetivos: Caracterizar desde el punto de vista morfo-anatómico las micromorphology and quality control method for this plant. -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Region 4 Threatened, Endangered and Sensitive Species List

INTERMOUNTAIN REGION (R4) THREATENED, ENDANGERED, PROPOSED, AND, SENSITIVE SPECIES June 2016 KNOWN / SUSPECTED DISTRIBUTION BY FOREST STATUS FOREST ENDANGERED ASH BOI B-T CAR CHA DIX FIS HUM M-L PAY SAL SAW TAR TOI UIN W-C MAMMALS Black-footed ferret 3/11/67 o o Mustela nigripes Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep Ovis canadensis X sierra January 3, 2000 BIRDS Southwestern willow flycatcher 2/27/95 X ? Empidonax traillii extimus ED 3/29/95 Whooping crane 3/11/67 X ? Grus americana REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS Sierra Nevada Yellow-legged Frog 06/30/2014 X Rana sierrae INSECTS Mt. Charleston Blue Butterfly 10/21/2013 X Icaricia shasta charlestonensis FISH June sucker 3/31/86 o o Chasmistes liorus Bonytail chub 4/23/80 o o o o o o o Gila elegans Humpback chub 3/11/67 o o o o o o o Gila cypha Colorado pike minnow 3/11/67 o o o o o o o Ptychocheilus lucius Kendall Warm Springs dace 10/13/70 X Rhinichthys osculus Proposed, Endangered, Threatened, and Sensitive Species List, R4 Page 2 of 19 ENDANGERED ASH BOI B-T CAR CHA DIX FIS HUM M-L PAY SAL SAW TAR TOI UIN W-C Sockeye salmon, (Snake River0 11/20/91 + + + X Oncorhynchus nerka (CH 12/28/98) Razorback sucker 10/23/91 o o o o o o o Xyrauchen texanus (ED 11/22/91) Sturgeon, pallid o Scaphirhynchus albus PLANTS San Rafael cactus X Pediocactus despainii Clay phacelia 09/28/78 ? X Phacelia argillacea THREATENED ASH BOI B-T CAR CHA DIX FIS HUM M-L PAY SAL SAW TAR TOI UIN W-C MAMMALS Canada lynx 4/15/00 X X X X X X ? ? Lynx canadensis Grizzly bear 9/21/2009 X X Ursus arctos horribilis Gray wolf (Wyoming Rocky -

Analysis of Paralogs in Target Enrichment Data Pinpoints Multiple Ancient Polyploidy Events

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.261925; this version posted August 23, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 1 Analysis of paralogs in target enrichment data pinpoints multiple ancient polyploidy events 2 in Alchemilla s.l. (Rosaceae). 3 4 Diego F. Morales-Briones1.2,*, Berit Gehrke3, Chien-Hsun Huang4, Aaron Liston5, Hong Ma6, 5 Hannah E. Marx7, David C. Tank2, Ya Yang1 6 7 1Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, 1445 Gortner 8 Avenue, St. Paul, MN 55108, USA 9 2Department of Biological Sciences and Institute for Bioinformatics and Evolutionary Studies, 10 University of Idaho, 875 Perimeter Drive MS 3051, Moscow, ID 83844, USA 11 3University Gardens, University Museum, University of Bergen, Mildeveien 240, 5259 12 Hjellestad, Norway 13 4State Key Laboratory of Genetic Engineering and Collaborative Innovation Center of Genetics 14 and Development, Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Biodiversity and Ecological 15 Engineering, Institute of Plant Biology, Center of Evolutionary Biology, School of Life Sciences, 16 Fudan University, Shanghai 200433, China 17 5Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University, 2082 Cordley Hall, 18 Corvallis, OR 97331, USA 19 6Department of Biology, the Huck Institute of the Life Sciences, the Pennsylvania State 20 University, 510D Mueller Laboratory, University Park, PA 16802 USA 21 7Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 22 48109-1048, USA 23 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.261925; this version posted August 23, 2020. -

ED45E Rare and Scarce Species Hierarchy.Pdf

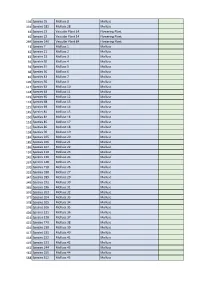

104 Species 55 Mollusc 8 Mollusc 334 Species 181 Mollusc 28 Mollusc 44 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 45 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 269 Species 149 Vascular Plant 84 Flowering Plant 13 Species 7 Mollusc 1 Mollusc 42 Species 21 Mollusc 2 Mollusc 43 Species 22 Mollusc 3 Mollusc 59 Species 30 Mollusc 4 Mollusc 59 Species 31 Mollusc 5 Mollusc 68 Species 36 Mollusc 6 Mollusc 81 Species 43 Mollusc 7 Mollusc 105 Species 56 Mollusc 9 Mollusc 117 Species 63 Mollusc 10 Mollusc 118 Species 64 Mollusc 11 Mollusc 119 Species 65 Mollusc 12 Mollusc 124 Species 68 Mollusc 13 Mollusc 125 Species 69 Mollusc 14 Mollusc 145 Species 81 Mollusc 15 Mollusc 150 Species 84 Mollusc 16 Mollusc 151 Species 85 Mollusc 17 Mollusc 152 Species 86 Mollusc 18 Mollusc 158 Species 90 Mollusc 19 Mollusc 184 Species 105 Mollusc 20 Mollusc 185 Species 106 Mollusc 21 Mollusc 186 Species 107 Mollusc 22 Mollusc 191 Species 110 Mollusc 23 Mollusc 245 Species 136 Mollusc 24 Mollusc 267 Species 148 Mollusc 25 Mollusc 270 Species 150 Mollusc 26 Mollusc 333 Species 180 Mollusc 27 Mollusc 347 Species 189 Mollusc 29 Mollusc 349 Species 191 Mollusc 30 Mollusc 365 Species 196 Mollusc 31 Mollusc 376 Species 203 Mollusc 32 Mollusc 377 Species 204 Mollusc 33 Mollusc 378 Species 205 Mollusc 34 Mollusc 379 Species 206 Mollusc 35 Mollusc 404 Species 221 Mollusc 36 Mollusc 414 Species 228 Mollusc 37 Mollusc 415 Species 229 Mollusc 38 Mollusc 416 Species 230 Mollusc 39 Mollusc 417 Species 231 Mollusc 40 Mollusc 418 Species 232 Mollusc 41 Mollusc 419 Species 233 -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Introduction to Common Native & Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska

Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska Cover photographs by (top to bottom, left to right): Tara Chestnut/Hannah E. Anderson, Jamie Fenneman, Vanessa Morgan, Dana Visalli, Jamie Fenneman, Lynda K. Moore and Denny Lassuy. Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska This document is based on An Aquatic Plant Identification Manual for Washington’s Freshwater Plants, which was modified with permission from the Washington State Department of Ecology, by the Center for Lakes and Reservoirs at Portland State University for Alaska Department of Fish and Game US Fish & Wildlife Service - Coastal Program US Fish & Wildlife Service - Aquatic Invasive Species Program December 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ............................................................................ x Introduction Overview ............................................................................. xvi How to Use This Manual .................................................... xvi Categories of Special Interest Imperiled, Rare and Uncommon Aquatic Species ..................... xx Indigenous Peoples Use of Aquatic Plants .............................. xxi Invasive Aquatic Plants Impacts ................................................................................. xxi Vectors ................................................................................. xxii Prevention Tips .................................................... xxii Early Detection and Reporting -

Conserving Europe's Threatened Plants

Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation By Suzanne Sharrock and Meirion Jones May 2009 Recommended citation: Sharrock, S. and Jones, M., 2009. Conserving Europe’s threatened plants: Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Botanic Gardens Conservation International, Richmond, UK ISBN 978-1-905164-30-1 Published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3BW, UK Design: John Morgan, [email protected] Acknowledgements The work of establishing a consolidated list of threatened Photo credits European plants was first initiated by Hugh Synge who developed the original database on which this report is based. All images are credited to BGCI with the exceptions of: We are most grateful to Hugh for providing this database to page 5, Nikos Krigas; page 8. Christophe Libert; page 10, BGCI and advising on further development of the list. The Pawel Kos; page 12 (upper), Nikos Krigas; page 14: James exacting task of inputting data from national Red Lists was Hitchmough; page 16 (lower), Jože Bavcon; page 17 (upper), carried out by Chris Cockel and without his dedicated work, the Nkos Krigas; page 20 (upper), Anca Sarbu; page 21, Nikos list would not have been completed. Thank you for your efforts Krigas; page 22 (upper) Simon Williams; page 22 (lower), RBG Chris. We are grateful to all the members of the European Kew; page 23 (upper), Jo Packet; page 23 (lower), Sandrine Botanic Gardens Consortium and other colleagues from Europe Godefroid; page 24 (upper) Jože Bavcon; page 24 (lower), Frank who provided essential advice, guidance and supplementary Scumacher; page 25 (upper) Michael Burkart; page 25, (lower) information on the species included in the database. -

Pala Park Habitat Assessment

Pala Park Bank Stabilization Project: Geotechnical Exploration TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1.0 COUNTY OF RIVERSIDE ATTACHMENTS Biological Report Summary Report (Attachment E-3) Level of Significance Checklist (Attachment E-4) Biological Resources Map (Attachment E-5) Site Photographs (Attachment E-6) SECTION 2.0 HABITAT ASSESSMENT General Site Information ............................................................................................................... 1 Methods ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Existing Conditions ....................................................................................................................... 4 Special Status Resources ............................................................................................................. 8 Other Issues ................................................................................................................................ 14 Recommendations ...................................................................................................................... 14 References .................................................................................................................................. 16 LIST OF TABLES Page 1 Special Status Plant Species Known to Occur in the Vicinity of the Survey Area ........... 10 2 Chaparral Sand-Verbena Populations Observed in the Survey Area ............................. 12 3 Paniculate Tarplant -

San Bruno Mountain Habitat Conservation Plan Year

SAN BRUNO MOUNTAIN HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN YEAR 2019-20 ACTIVITIES REPORT FOR FEDERALLY LISTED SPECIES Endangered Species 10(a)(1)(B) Permit TE215574-6 Prepared By: Evan Cole San Mateo County Parks Department 455 County Center, 4th Floor Redwood City, CA 94063 December 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................7 A. Covered Species Population Status ................................................................................... 7 2019 MISSION BLUE STATUS ......................................................................................................................... 8 2020 CALLIPPE SILVERSPOT STATUS.............................................................................................................. 8 2020 SAN BRUNO ELFIN STATUS ................................................................................................................... 9 RARE PLANT STATUS ..................................................................................................................................... 9 II. STATUS OF SPECIES OF CONCERN .........................................................................9 A. Mission Blue Butterfly (Icaricia icarioides missionensis) .............................................. 9 METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................................................................... 10 RESULTS ..................................................................................................................................................... -

ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names 7Th Edition

ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names th 7 Edition ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. M. Schori Published by All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be The Internation Seed Testing Association (ISTA) reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted Zürichstr. 50, CH-8303 Bassersdorf, Switzerland in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior ©2020 International Seed Testing Association (ISTA) permission in writing from ISTA. ISBN 978-3-906549-77-4 ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names 1st Edition 1966 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Prof P. A. Linehan 2nd Edition 1983 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. H. Pirson 3rd Edition 1988 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. W. A. Brandenburg 4th Edition 2001 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 5th Edition 2007 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 6th Edition 2013 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 7th Edition 2019 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. M. Schori 2 7th Edition ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names Content Preface .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Symbols and Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... -

CHANGES in the DISTRIBUTION RANGE of POTENTILLA TUCUMANENS/S (ROSACEAE), an ENDANGERED CRYPTIC Speciesi

ISSN 0373-580 X Bol. Soc. Argent. Bot. 36 (1-2): 151 - 157. 2001 CHANGES IN THE DISTRIBUTION RANGE OF POTENTILLA TUCUMANENS/S (ROSACEAE), AN ENDANGERED CRYPTIC SPECIESi MARTA ARIAS23, JUAN DIAZ RICCI4 and ATILIO CASTAGNARO4 Summary: A correct taxonomic identification is essential for the preservation of biodiversity. In this paper we present simple morphological characters for the identification of the new species recently described, Potentilla tucumanensis. The reproductive period of this species occupies about 10% of the last part of its lifecycle, is considered cryptic because in the vegetative stage it has many morphological similarities with other cohabiting related species; it can be easily confused with them and it is reproductively isolated. Our study also revealed that for the last hundred years P. tucumanensis has suffered a dramatic habitat retraction. Possible causes of this area retraction are discussed. If P tucumanensis had not been recognized asa new species, it would have most likely disappeared without being noticed. Key words: Potentilla tucumanensis, Duchesnea indica, Fragaria vesca, endangered species, cryptic species, anthropogenic changes. Resumen: Cambios en el rango de distribución de Potentilla tucumanensis (Rosaceae), una especie críptica en peligro de extinción. Una correcta identificación taxonómica es esencial para la preservación de la biodiversidad. En este trabajo se presentan caracteres morfológicos sencillos para diferenciar la nueva especip, Potentilla tucumanensis recientemente descripta. Esta especie, cuyo período reproductivo ocupa el 10% final de su ciclo de vida, es considerada críptica debido a que puede ser confundida por su similitud en estado vegetativo, con especies con las cuales cohabita y está aislada reproductivamente. Además, se muestra que en los últimos cien años, P.