West Ready for KC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

17-Chapter-16-Versewise.Pdf

BHAGAVAD GITA Chapter 16 Daivasura-Sampad-Vibhaga Yoga (The Divine and Demoniac Natures Defined) 1 Chapter 16 Introduction : 1) Of vain hopes, of vain actions, of vain knowledge and senseless (devoid of discrimination), they verily are possessed of the delusive nature of raksasas and asuras. [Chapter 9 – Verse 12] Asura / Raksasa Sampad : • Moghasah, Mogha Karmanah – false hopes from improper actions. Vicetasah : • Lack of discrimination. • Binds you to samsara. 2) But the Mahatmas (great souls), O Partha, partaking of My divine nature, worship Me with a single mind (with a mind devoted to nothing else), knowing Me as the imperishable source of all beings. [Chapter 9 – Verse 13] Daivi Sampad : • Seek Bagawan. • Helps to gain freedom from Samsara. 2 • What values of the mind constitute spiritual disposition and demonic disposition? Asura – Sampad Daivi Sampad - Finds enjoyment only in - Make choice as per value sense objects. structure, not as per - Will compromise to gain convenience. the end. • Fields of experiences - Kshetram change but the subject Kshetrajna, knower is one in all fields. • Field is under influence of different temperaments – gunas and hence experiences vary from individual to individual. • Infinite is nature of the subject, transcendental state of perfection and pure knowledge (Purushottama). • This chapter describes how the knower pulsates through disciplined or undisciplined field of experience. • Field is the 3 gunas operative in the minds of individuals. • Veda is a pramana only for prepared mind. Values are necessary to gain knowledge – chapter 13, 14, 15 are direct means to liberation through Jnana yoga. Chapter 16, 17 are values to gain knowledge. 3 Chapter 16 - Summary Verse 1 - 3 Verse 4 - 21 Verse 22 Daivi Sampat (Spiritual) – 18 Values Asuri Sampat (Materialistic) – 18 Values - Avoid 3 traits and adopt daivi sampat and get qualifications 1. -

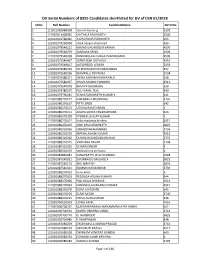

DV Sl No.S of 8255 Cen 01 2018.Xlsx

DV Serial Numbers of 8255 Candidates shortlisted for DV of CEN 01/2018 Sl No. Roll Number CandidateName DV Sl No. 1 111021092980008 ramesh kumar g 2592 2 121001013400035 CHITYALA RAVIKANTH 4506 3 121001022780082 JUJJAVARAPU SRIMANTH 635 4 121001079230008 shaik naseer ahammad 636 5 121001079540221 KAMADI JAGADEESH VARMA 4507 6 121001079540279 SANDAKA SRINU 4508 7 121001079540338 KANDREGULA DURGA PHANIKUMAR 4509 8 121001079540407 VENKATESH GUTHULA 4510 9 121001079540817 KATIKIREDDI LOKESH 2593 10 121001079580229 DILEEPKUMAR DEVARAKONDA 637 11 121001079580296 MAMPALLI PRIYANKA 3734 12 121001079580321 CHINA AKKAIAH KANKANALA 638 13 121001079580337 NAGALAKSHMI PONNURI 4511 14 121001079640078 BHUKYA DASARADH 639 15 121001079780207 PULI VIMAL TEJA 640 16 121001079790242 VENKATABHARATH KUMAR Y 641 17 121001080270122 KALLAPALLI ARUNBABU 3735 18 121001080270167 PITTA BABJI 642 19 121001080270174 UDDISA RAMCHARAN 1 20 121001080270211 ADAPA SURYA CHAKRADHARA 643 21 121001080270328 PYDIMALLA AJAY KUMAR 2 22 121001080270412 Kalla chaitanya krishna 4512 23 121001080270493 JAMI KASI VISWANATH 6822 24 121001080310065 DARABOINA RAMBABU 3736 25 121001080310176 SEPENA ASHOK KUMAR 4513 26 121001080310262 DUNNA HEMASUNDARA RAO 3737 27 121001080310275 VANDANA PAVAN 3738 28 121001080310395 DUNNA DINESH 3 29 121001080310479 vattikuti siva srinivasu 4 30 121001083840041 KANAPARTHI JAYA CHANDRA 2594 31 121001087540021 SIVUNNAIDU MUDADLA 6823 32 121001087540116 ARJI MAHESH 6824 33 121001087540321 KOMMA RAVISANKAR 3739 34 121001088270010 kona kiran 5 35 121001088270019 -

The Sanskrit Epics

The Sanskrit Epics The Sanskrit Epics, J. L. Brockington, BRILL, 1998, 1998, 9004102604, 9789004102606, 596 pages, Mah bh rata (including Harivam a) and R m yan a, the two great Sanskrit Epics central to the whole of Indian Culture, form the subject of this new work.The book begins by examining the relationship of the epics to the Vedas and the role of the bards who produced them. The core of the work, a study of the linguistic and stylistic features of the epics, precedes the examination of the material culture, the social, economic and political aspects, and the religious aspects. The final chapter presents the wider picture and in conclusion even looks into the future of epic studies.In this long overdue survey work the author synthesizes the results of previous scholarship in the field. Herewith a coherent view is built up of the nature and the significance of these two central epics, both in themselves, and in relation to Indian culture as a whole. file download hehezu.pdf Danielle Feller, This is an introduction to philosophy but with a difference. Through out the book metaphysical issues are shown to be rooted in the history of philosophy. At the same time the, ISBN:8120820088, 369 pages, Jan 1, 2004, Gods, Hindu, in literature, Sanskrit Epics Sanskrit pdf file This volume brings together John Brockington's articles on the Ramayana and Mahabharata, relating them to wider issues in the study of the Sanskrit epics, Epic poetry, Sanskrit, Epic Threads, John Brockington on the Sanskrit Epics, 366 pages, J. L. Brockington, Mary Brockington, Greg Bailey, 2000, IND:30000087943290 Anna S. -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA PARVA translated by Kesari Mohan Ganguli In parentheses Publications Sanskrit Series Cambridge, Ontario 2002 Salya Parva Section I Om! Having bowed down unto Narayana and Nara, the most exalted of male beings, and the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. Janamejaya said, “After Karna had thus been slain in battle by Savyasachin, what did the small (unslaughtered) remnant of the Kauravas do, O regenerate one? Beholding the army of the Pandavas swelling with might and energy, what behaviour did the Kuru prince Suyodhana adopt towards the Pandavas, thinking it suitable to the hour? I desire to hear all this. Tell me, O foremost of regenerate ones, I am never satiated with listening to the grand feats of my ancestors.” Vaisampayana said, “After the fall of Karna, O king, Dhritarashtra’s son Suyodhana was plunged deep into an ocean of grief and saw despair on every side. Indulging in incessant lamentations, saying, ‘Alas, oh Karna! Alas, oh Karna!’ he proceeded with great difficulty to his camp, accompanied by the unslaughtered remnant of the kings on his side. Thinking of the slaughter of the Suta’s son, he could not obtain peace of mind, though comforted by those kings with excellent reasons inculcated by the scriptures. Regarding destiny and necessity to be all- powerful, the Kuru king firmly resolved on battle. Having duly made Salya the generalissimo of his forces, that bull among kings, O monarch, proceeded for battle, accompanied by that unslaughtered remnant of his forces. Then, O chief of Bharata’s race, a terrible battle took place between the troops of the Kurus and those of the Pandavas, resembling that between the gods and the Asuras. -

Towards a Critical Edition of Śaṅkara's 'Longer' Aitareyopaniṣadbhāṣya: a Preliminary Report Based on Two Cambridg

Hugo David Towards a Critical Edition of Śaṅkara’s ‘Longer’ Aitareyopaniṣadbhāṣya: a Preliminary Report based on two Cambridge Manuscripts Abstract: This article presents a fresh assessment of evidence for the existence of Śaṅkara’s ‘longer’ commentary on the Aitareyopaniṣad, a sub-section of the Aitar- eyāraṇyaka (AiĀ). While most printed editions of the Bhāṣya consider that it covers only three adhyāyas of the Āraṇyaka (AiĀ 2.4-6/7), a much more comprehensive work, bearing on the whole of AiĀ 2 and 3, is preserved in manuscripts. In the first part of the article, I argue that the ascription of this ‘longer’ gloss to Śaṅkara is likely to be justified, building on previous scholarship (A.B. Keith, S.K. Belvalkar) as well as on my own inspection of two manuscripts of the work, newly identified in the Cambridge University Library. Questions are also raised as to the constitution of the Upaniṣadic canon(s) and the role of commentaries in that process. The second part of the essay provides a comprehensive survey of the material (manuscript and print) available for a first critical edition of this important, though mostly neglected work by the great Vedāntin. || Research for the present study was started during my stint in Cambridge in 2013–14, for which I benefitted of the generous support of the British Royal Society (Newton International Fellow- ship), and during which I had the privilege to participate as a regular external collaborator in the Sanskrit Manuscripts Project. I thank the three editors of this volume for facilitating me access to the Cambridge collection in innumerable ways, for sharing their knowledge and expertise of Sanskrit manuscripts, and for allowing me to take part in their endeavour. -

The Atharvaveda and Its Paippalādaśākhā Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen

The Atharvaveda and its Paippalādaśākhā Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen To cite this version: Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen. The Atharvaveda and its Paippalādaśākhā: Historical and philological papers on a Vedic tradition. Arlo Griffiths; Annette Schmiedchen. 11, Shaker, 2007, Indologica Halensis, 978-3-8322-6255-6. halshs-01929253 HAL Id: halshs-01929253 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01929253 Submitted on 5 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Griffiths, Arlo, and Annette Schmiedchen, eds. 2007. The Atharvaveda and Its Paippalādaśākhā: Historical and Philological Papers on a Vedic Tradition. Indologica Halensis 11. Aachen: Shaker. Contents Arlo Griffiths Prefatory Remarks . III Philipp Kubisch The Metrical and Prosodical Structures of Books I–VII of the Vulgate Atharvavedasam. hita¯ .....................................................1 Alexander Lubotsky PS 8.15. Offense against a Brahmin . 23 Werner Knobl Zwei Studien zum Wortschatz der Paippalada-Sam¯ . hita¯ ..................35 Yasuhiro Tsuchiyama On the meaning of the word r¯as..tr´a: PS 10.4 . 71 Timothy Lubin The N¯ılarudropanis.ad and the Paippal¯adasam. hit¯a: A Critical Edition with Trans- lation of the Upanis.ad and Nar¯ ayan¯ . a’s D¯ıpik¯a ............................81 Arlo Griffiths The Ancillary Literature of the Paippalada¯ School: A Preliminary Survey with an Edition of the Caran. -

Cyavana Helps Ashvins, Prometheus Helps Humans

Nick Allen: Cyavana Helps Aśvins, Prometheus Helps Humans 13 Cyavana Helps Ashvins, Prometheus Helps Humans: A Myth About Sacrifice NICK ALLEN University of Oxford Though founded by linguists, the field of Indo-European Studies has developed two offshoots or annexes – the archaeological and the socio-cultural. The sociocultural can be subdivided in various ways, for instance into domains (social structure, pantheon, myth/epic and ritual, legal systems, and so on), and/or by regions – which is to say, by branches of the language family. One tempting regional comparison is between India and Greece. This too can be subdivided, for instance on the basis of the texts used for the comparison. As regards India, much work has focused on the Vedas, especially the Rig Veda, on the grounds that ‘earlier’ texts are more likely to contain Indo-European heritage than ‘later’ ones.1 However, contrary to this reasonable expectation, the allusive, elusive – even cryptic – Rig Veda offers less narrative material suitable for comparison with Greece than does the copious epic tradition, especially the vast Mahābhārata. A certain amount has been done on Homer-Mahābhārata comparison (e.g., Allen 2010), and another paper from the same point of view (Allen 2005) presented a Hesiod-Mahābhārata comparison. The present paper continues the latter direction of study, though by no means exhausting its possibilities. The comparison concerns the myth of origin of a ritual. The Greek myth concerns animal sacrifice in general, while the Sanskrit is more specialised in that it concerns only soma sacrifices. The first tasks are to introduce the helpers who appear in my title and whom I call ‘the protagonists’, and to contextualise the stories about them. -

Vidura Speaks: a Study of the Viduranīti and Its Reception History

Vidura Speaks: A Study of the Viduranīti and its Reception History Sravani Kanamarlapudi A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2019 Committee: Richard Salomon Heidi Pauwels Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2019 Sravani Kanamarlapudi University of Washington Abstract Vidura Speaks: A Study of the Viduranīti and its Reception History Sravani Kanamarlapudi Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Richard Salomon Department of Asian Languages and Literature This thesis offers a close reading of an important yet neglected didactic text from the Indian epic Mahābhārata, namely the Viduranīti, which is a nocturnal politico-moral counsel of Vidura to Dhr̥ tarāṣṭra. Adopting the currently prevalent trend in Mahābhārata scholarship, the received epic is approached as a work of literature by treating its didactic segments as constitutive parts of the unfolding narrative, rather than simply viewing the received epic as an outcome of later didactic accretions on a supposed earlier core narrative. As such, the Viduranīti is juxtaposed thematically with the epic’s story, particularly with the epic’s portrayal of Vidura, and structurally with other didactic portions of the epic and the entire epic as a whole. The former analysis reveals that both Vidura and the Viduranīti are centered around the categories of dharma and artha, while the latter exposes similarities in the literary architectonics of the Viduranīti and other didactic tracts. Finally, a case study investigates why the Viduranīti was canonized in a modern Hindu community. Situating this textual reframing in the modern socio-historical context, I argue for the need to focus on reception histories of early South Asian texts. -

The Sama Veda

TRANSLATION"~ or THE SAMHITA' or TJIE SA'MA VEDA. BY THE REV. J. STEVENSON, . - · · /i~i\ _N_j_Nff;··~ 1.~· ~\ 1~ LIBRARY ~\ --..: O' -~' OR.FI.I.RIOB.&.RAN ....,·, '~,. '~~:~~'.~, ~'ffeJ: LONDOrl, 'f,;, '_0

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings & Speeches Vol. 4

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) BLANK DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 4 Compiled by VASANT MOON Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches Vol. 4 First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : October 1987 Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014 ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9 Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead. © Secretary Education Department Government of Maharashtra Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/- Publisher: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India 15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001 Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589 Fax : 011-23320582 Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032 for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee Printer M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. Ltd., N. H. 10, Village-Rohad, Distt. Jhajjar, Haryana Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment & Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Kumari Selja MESSAGE Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chief Architect of Indian Constitution was a scholar par excellence, a philosopher, a visionary, an emancipator and a true nationalist. He led a number of social movements to secure human rights to the oppressed and depressed sections of the society. He stands as a symbol of struggle for social justice. The Government of Maharashtra has done a highly commendable work of publication of volumes of unpublished works of Dr. Ambedkar, which have brought out his ideology and philosophy before the Nation and the world. In pursuance of the recommendations of the Centenary Celebrations Committee of Dr. -

Hymns to the Mystic Fire

16 Hymns to the Mystic Fire VOLUME 16 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO © Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust 2013 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA Hymns To The Mystic Fire Publisher’s Note The present volume comprises Sri Aurobindo’s translations of and commentaries on hymns to Agni in the Rig Veda. It is divided into three parts: Hymns to the Mystic Fire: The entire contents of a book of this name that was published by Sri Aurobindo in 1946, consisting of selected hymns to Agni with a Fore- word and extracts from the essay “The Doctrine of the Mystics”. Other Hymns to Agni: Translations of hymns to Agni that Sri Aurobindo did not include in the edition of Hymns to the Mystic Fire published during his lifetime. An appendix to this part contains his complete transla- tions of the first hymn of the Rig Veda, showing how his approach to translating the Veda changed over the years. Commentaries and Annotated Translations: Pieces from Sri Aurobindo’s manuscripts in which he commented on hymns to Agni or provided annotated translations of them. Some translations of hymns addressed to Agni are included in The Secret of the Veda, volume 15 of THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO. That volume consists of all Sri Aurobindo’s essays on and translations of Vedic hymns that appeared first in the monthly review Arya between 1914 and 1920. His writings on the Veda that do not deal primarily with Agni and that were not published in the Arya are collected in Vedic and Philological Studies, volume 14 of THE COMPLETE WORKS. -

JAY MANGALAMURTI (Aarti to Shri Ganesha)

Aartis 1 JAY MANGALAMURTI (Aarti to Shri Ganesha) Sukha Karta Dukha Harta Varta Vighnachi You are the One who offers happiness and removes sorrows at the time of danger. Nurvi Purvi Prem Krupa Jayachi You offer tender lots of love and blessings Sarvangi Sunder Uti Shendurachi You have red paste on Your body Kanthi Jhalke Mal Mukta Falanchi and wear a pearl necklace. Chorus: Jai Dev., Jai Dev., Jai Mangalamurti Victory to You, most auspicious One! Darshan Matre Mana Kamana Purti Even by Your glance You fulfill the desires in our minds. Jai Dev., Jai Dev. Victory, O God! Ratna Khachita Fara Tuza Gauri Kumara The Goddess Gauri is present by Your side Chandanachi Uti Kumkum Keshara Bedecked with gems and jewellery. Hire Jadita Muguta Shobhato Bara The diamond studded crown on Your head adds to Your gracefulness, Runjhunti Nupure Charni Ghagariya The anklets on Your feet make heavenly music. Lambodar Pitambar Fanivar Bandhana I always have in mind Your long belly, Your pitambar (silk dhoti), Kundalini on Your stomach Saral Sonda Vakratunda Trinayana Your straight trunk, Your innocent face with its three eyes. Das. Ramacha Vat. Pahe Sadana The servant of Shri Rama is waiting for You in this house (body). Sankashti Pavave Nirvani Rakshave Please protect us from calamities and sorrows. O Highest amongst Gods, we bow to You! Survar Vandana Aartis 2 ARATI NIRMALA MATA Chorus: Arati Nirmala Mata ) Aarti to Mother Nirmala > Charni Thevila Me Mata ) (x2) I have surrendered to You Arati Nirmala Mata Aarti to Mother Nirmala Adi Shakti Kundalini Oh Primordial power of the Kundalini who Sarva Vishwachi Janani is the Mother of the Universe Nirguna He Rupa Tuzhe Your form is beyond the Gunas and now Zahli Saguna Tu Ata You have become Saguna (of good qualities).