Read Native Pollinators and Agriculture in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clear Plastic Bags of Bark Mulch Trap and Kill Female Megachile (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) Searching for Nesting Sites

JOURNAL OF THE KANSAS ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY 92(4), 2019, pp. 649-654 SHORT COMMUNICATION Clear Plastic Bags of Bark Mulch Trap and Kill Female Megachile (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) Searching for Nesting Sites Casey M. Delphia1*, Justin B. Runyon2, and Kevin M. O’Neill3 ABSTRACT: In 2017, we found 17 dead females of Megachile frigida Smith in clear plastic bags of com- posted bark mulch in a residential yard in Bozeman, Montana, USA. Females apparently entered bags via small ventilation holes, then became trapped and died. To investigate whether this is a common source of mortality, we deployed unmodified bags of mulch and those fitted with cardboard tubes (as potential nest sites) at three nearby sites in 2018. We found two dead M. frigida females and five completed leaf cells in one of these bags of mulch fitted with cardboard tubes; two male M. frigida emerged from these leaf cells. In 2018, we also discovered three dead female M. frigida and three dead females of a second leafcutter bee species, Megachile gemula Cresson, in clear bags of another type of bark mulch. Both mulches emitted nearly identical blends of volatile organic compounds, suggesting their odors could attract females searching for nesting sites. These findings suggest that more research is needed to determine how common and wide- spread this is for Megachile species that nest in rotting wood and if there are simple solutions to this problem. KEYWORDS: Leafcutter bees, solitary bees, cavity-nesting bees, Apoidea, wild bees, pollinators, Megachile frigida, Megachile gemula The leafcutter bees Megachile frigida Smith, 1853 and Megachile gemula Cresson, 1878 (Megachilidae) are widespread in North America (Mitchell 1960; Michener, 2007; Sheffield et al., 2011). -

Assessing the Presence and Distribution of 23 Hawaiian Yellow-Faced Bee Species on Lands Adjacent to Military Installations on O‘Ahu and Hawai‘I Island

The Hawai`i-Pacific Islands Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Unit & Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI`I AT MĀNOA Dr. David C. Duffy, Unit Leader Department of Botany 3190 Maile Way, St. John #408 Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822 Technical Report 185 Assessing the presence and distribution of 23 Hawaiian yellow-faced bee species on lands adjacent to military installations on O‘ahu and Hawai‘i Island September 2013 Karl N. Magnacca1 and Cynthia B. K. King 2 1 Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Department of Botany, 3190 Maile Way Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822 2 Hawaii Division of Forestry & Wildlife Native Invertebrate Program 1151 Punchbowl Street, Room 325 Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 PCSU is a cooperative program between the University of Hawai`i and U.S. National Park Service, Cooperative Ecological Studies Unit. Author Contact Information: Karl N. Magnacca. Phone: 808-554-5637 Email: [email protected] Hawaii Division of Forestry & Wildlife Native Invertebrate Program 1151 Punchbowl Street, Room 325 Honolulu, Hawaii 96813. Recommended Citation: Magnacca, K.N. and C.B.K. King. 2013. Assessing the presence and distribution of 23 Hawaiian yellow- faced bee species on lands adjacent to military installations on O‘ahu and Hawai‘i Island. Technical Report No. 185. Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, University of Hawai‘i, Honolulu, Hawai‘i. 39 pp. Key words: Hylaeus, Colletidae, Apoidea, Hymenoptera, bees, insect conservation Place key words: Oahu, Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, Puu Waawaa, Mauna Kea, Pohakuloa, North Kona Editor: David C. Duffy, PCSU Unit Leader (Email: [email protected]) Series Editor: Clifford W. Morden, PCSU Deputy Director (Email: [email protected]) About this technical report series: This technical report series began in 1973 with the formation of the Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa. -

A Review of Sampling and Monitoring Methods for Beneficial Arthropods

insects Review A Review of Sampling and Monitoring Methods for Beneficial Arthropods in Agroecosystems Kenneth W. McCravy Department of Biological Sciences, Western Illinois University, 1 University Circle, Macomb, IL 61455, USA; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-309-298-2160 Received: 12 September 2018; Accepted: 19 November 2018; Published: 23 November 2018 Abstract: Beneficial arthropods provide many important ecosystem services. In agroecosystems, pollination and control of crop pests provide benefits worth billions of dollars annually. Effective sampling and monitoring of these beneficial arthropods is essential for ensuring their short- and long-term viability and effectiveness. There are numerous methods available for sampling beneficial arthropods in a variety of habitats, and these methods can vary in efficiency and effectiveness. In this paper I review active and passive sampling methods for non-Apis bees and arthropod natural enemies of agricultural pests, including methods for sampling flying insects, arthropods on vegetation and in soil and litter environments, and estimation of predation and parasitism rates. Sample sizes, lethal sampling, and the potential usefulness of bycatch are also discussed. Keywords: sampling methodology; bee monitoring; beneficial arthropods; natural enemy monitoring; vane traps; Malaise traps; bowl traps; pitfall traps; insect netting; epigeic arthropod sampling 1. Introduction To sustainably use the Earth’s resources for our benefit, it is essential that we understand the ecology of human-altered systems and the organisms that inhabit them. Agroecosystems include agricultural activities plus living and nonliving components that interact with these activities in a variety of ways. Beneficial arthropods, such as pollinators of crops and natural enemies of arthropod pests and weeds, play important roles in the economic and ecological success of agroecosystems. -

Newsletter of the Biological Survey of Canada

Newsletter of the Biological Survey of Canada Vol. 40(1) Summer 2021 The Newsletter of the BSC is published twice a year by the In this issue Biological Survey of Canada, an incorporated not-for-profit From the editor’s desk............2 group devoted to promoting biodiversity science in Canada. Membership..........................3 President’s report...................4 BSC Facebook & Twitter...........5 Reminder: 2021 AGM Contributing to the BSC The Annual General Meeting will be held on June 23, 2021 Newsletter............................5 Reminder: 2021 AGM..............6 Request for specimens: ........6 Feature Articles: Student Corner 1. City Nature Challenge Bioblitz Shawn Abraham: New Student 2021-The view from 53.5 °N, Liaison for the BSC..........................7 by Greg Pohl......................14 Mayflies (mainlyHexagenia sp., Ephemeroptera: Ephemeridae): an 2. Arthropod Survey at Fort Ellice, MB important food source for adult by Robert E. Wrigley & colleagues walleye in NW Ontario lakes, by A. ................................................18 Ricker-Held & D.Beresford................8 Project Updates New book on Staphylinids published Student Corner by J. Klimaszewski & colleagues......11 New Student Liaison: Assessment of Chironomidae (Dip- Shawn Abraham .............................7 tera) of Far Northern Ontario by A. Namayandeh & D. Beresford.......11 Mayflies (mainlyHexagenia sp., Ephemerop- New Project tera: Ephemeridae): an important food source Help GloWorm document the distribu- for adult walleye in NW Ontario lakes, tion & status of native earthworms in by A. Ricker-Held & D.Beresford................8 Canada, by H.Proctor & colleagues...12 Feature Articles 1. City Nature Challenge Bioblitz Tales from the Field: Take me to the River, by Todd Lawton ............................26 2021-The view from 53.5 °N, by Greg Pohl..............................14 2. -

A Synthesis of the Pollinator Management Symposium

VICTORIA WOJCIK LISA SMITH WILLIAM CARROMERO AIMÉE CODE LAURIE DAVIES ADAMS SETH DAVIS SANDRA J. DEBANO CANDACE FALLON RICH HATFIELD SCOTT HOFFMAN BLACK JENNIFER HOPWOOD SARAH HOYLE THOMAS KAYE SARINA JEPSEN STEPHANIE MCKNIGHT LORA MORANDIN EMMA PELTON PAUL RHOADES KELLY ROURKE MARY ROWLAND WADE TINKHAM NEW RESEARCH AND BMPS IN NATURAL AREAS: A SYNTHESIS OF THE POLLINATOR MANAGEMENT SYMPOSIUM FROM THE 44TH NATURAL AREAS CONFERENCE, OCTOBER 2017 New Research and BMPs in Natural Areas: A Synthesis of the Pollinator Management Symposium from the 44th Natural Areas Conference, October 2017 Victoria Wojcik, Lisa Smith, William Carromero, Aimée Code, Laurie Davies Adams, Seth Davis, Sandra J. DeBano, Candace Fallon, Rich Hatfield, Scott Hoffman Black, Jennifer Hopwood, Sarah Hoyle, Thomas Kaye, Sarina Jepsen, Stephanie McKnight, Lora Morandin, Emma Pelton, Paul Rhoades, Kelly Rourke, Mary Rowland, and Wade Tinkham Index terms: bee competition, Best Management and suburban areas through habitat planting and Practices, forest management, grazing, restoration gardening shows the same positive trend of attracting seeding diverse communities of pollinators (Hernandez et al. 2009; Wojcik and McBride 2012). Less evidence exists INTRODUCTION for the restoration of natural landscapes; neverthe- less, case studies indicate that planting for pollinators Land managers face constant challenges when (Cane and Love 2016; Tonietto and Larkin 2018) or balancing multiple land use goals that include ensur- modifying management practices and seed mixes ing that keystone species are protected. As mindful (Galea et al. 2016; Harmon-Threatt and Chin 2016) stewards of our natural areas we aim to promote, indeed results in corresponding positive changes in secure, and enhance our natural landscapes and the the pollinator community: more pollinators using the species that make them their home. -

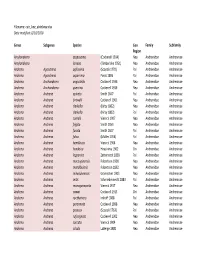

Anthophila List

Filename: cuic_bee_database. -

Wild Bee Declines and Changes in Plant-Pollinator Networks Over 125 Years Revealed Through Museum Collections

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2018 WILD BEE DECLINES AND CHANGES IN PLANT-POLLINATOR NETWORKS OVER 125 YEARS REVEALED THROUGH MUSEUM COLLECTIONS Minna Mathiasson University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Mathiasson, Minna, "WILD BEE DECLINES AND CHANGES IN PLANT-POLLINATOR NETWORKS OVER 125 YEARS REVEALED THROUGH MUSEUM COLLECTIONS" (2018). Master's Theses and Capstones. 1192. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/1192 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILD BEE DECLINES AND CHANGES IN PLANT-POLLINATOR NETWORKS OVER 125 YEARS REVEALED THROUGH MUSEUM COLLECTIONS BY MINNA ELIZABETH MATHIASSON BS Botany, University of Maine, 2013 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Biological Sciences: Integrative and Organismal Biology May, 2018 This thesis has been examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biological Sciences: Integrative and Organismal Biology by: Dr. Sandra M. Rehan, Assistant Professor of Biology Dr. Carrie Hall, Assistant Professor of Biology Dr. Janet Sullivan, Adjunct Associate Professor of Biology On April 18, 2018 Original approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. -

Demography and Molecular Ecology of the Solitary Halictid Lasioglossum Zonulum: with Observations on Lasioglossum Leucozonium

Demography and molecular ecology of the solitary halictid Lasioglossum zonulum: With observations on Lasioglossum leucozonium Alex N. M. Proulx, M.Sc. Biological Sciences (Ecology and Evolution) Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Faculty of Mathematics and Science, Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © 2020 Thesis Abstract Halictid bees are excellent models for questions of both evolutionary biology and molecular ecology. While the majority of Halictid species are solitary and many are native to North America, neither solitary nor native bees have been extensively studied in terms of their population genetics. This thesis studies the social behaviour, demographic patterns and molecular ecology of the solitary Holarctic sweat bee Lasioglossum zonulum, with comparisons to its well-studied sister species Lasioglossum leucozonium. I show that L. zonulum is bivoltine in the Niagara region of southern Ontario but is univoltine in a more northern region of southern Alberta. Measurements of size, wear and ovarian development of collected females revealed that Brood 1 offspring are not altruistic workers and L. zonulum is solitary. A large proportion of foundresses were also found foraging with well-developed ovaries along with their daughters, meaning L. zonulum is solitary and partially-bivoltine in the Niagara region. L. zonulum being solitary and univoltine in Calgary suggests that it is a demographically polymorphic and not socially polymorphic. Thus, L. zonulum represents a transitional evolutionary state between solitary and eusocial behaviour in bees. I demonstrate that Lasioglossum zonulum was introduced to North America at least once from Europe in the last 500 years, with multiple introductions probable. -

The Population Genetics of a Solitary Oligolectic Sweat Bee, Lasioglossum (Sphecodogastra) Oenotherae (Hymenoptera: Halictidae)

Heredity (2007) 99, 397–405 & 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0018-067X/07 $30.00 www.nature.com/hdy ORIGINAL ARTICLE The population genetics of a solitary oligolectic sweat bee, Lasioglossum (Sphecodogastra) oenotherae (Hymenoptera: Halictidae) A Zayed and L Packer 1Department of Biology, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Strong evidence exists for global declines in pollinator indicating that L. oenotherae’s sub-populations are experi- populations. Data on the population genetics of solitary encing ongoing gene flow. Southern populations of L. bees, especially diet specialists, are generally lacking. We oenotherae were significantly more likely to deviate from studied the population genetics of the oligolectic bee Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium and from genotypic equilibrium, Lasioglossum oenotherae, a specialist on the pollen of suggesting regional differences in gene flow and/or drift and evening primrose (Onagraceae), by genotyping 455 females inbreeding. Short-term Ne estimated using temporal changes from 15 populations across the bee’s North American range in allele frequencies in several populations ranged from at six hyper-variable microsatellite loci. We found significant B223 to 960. We discuss our findings in terms of the levels of genetic differentiation between populations, even at conservation genetics of specialist pollinators, a group of small geographic scales, as well as significant patterns of considerable ecological importance. isolation by distance. However, using multilocus genotype Heredity (2007) 99, 397–405; doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6801013; assignment tests, we detected 11 first-generation migrants published online 30 May 2007 Keywords: population structure; isolation by distance; linkage disequilibrium; migration; diet specialization; microsatellites Introduction their activities. However, population genetic studies of specialist pollinators have seldom been undertaken There is mounting evidence that pollinator assemblages, (Packer and Owen, 2001). -

Creating a Pollinator Garden for Native Specialist Bees of New York and the Northeast

Creating a pollinator garden for native specialist bees of New York and the Northeast Maria van Dyke Kristine Boys Rosemarie Parker Robert Wesley Bryan Danforth From Cover Photo: Additional species not readily visible in photo - Baptisia australis, Cornus sp., Heuchera americana, Monarda didyma, Phlox carolina, Solidago nemoralis, Solidago sempervirens, Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlii. These shade-loving species are in a nearby bed. Acknowledgements This project was supported by the NYS Natural Heritage Program under the NYS Pollinator Protection Plan and Environmental Protection Fund. In addition, we offer our appreciation to Jarrod Fowler for his research into compiling lists of specialist bees and their host plants in the eastern United States. Creating a Pollinator Garden for Specialist Bees in New York Table of Contents Introduction _________________________________________________________________________ 1 Native bees and plants _________________________________________________________________ 3 Nesting Resources ____________________________________________________________________ 3 Planning your garden __________________________________________________________________ 4 Site assessment and planning: ____________________________________________________ 5 Site preparation: _______________________________________________________________ 5 Design: _______________________________________________________________________ 6 Soil: _________________________________________________________________________ 6 Sun Exposure: _________________________________________________________________ -

A Systematic Literature Review

Tropical Ecology 58(1): 211–215, 2017 ISSN 0564-3295 © International Society for Tropical Ecology www.tropecol.com Diversity of native bees on Parkinsonia aculeata L. in Jammu region of North-West Himalaya UMA SHANKAR, D. P. ABROL*, DEBJYOTI CHATTERJEE & S. E. H. RIZVI Division of Entomology, Sher-e- Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences & Technology, Faculty of Agriculture, Chatha Jammu – 180009, J&K, India Abstract: A study was conducted in Jammu region of Jammu and Kashmir State to determine the species composition and relative abundance of pollinators on Parkinsonia aculeata L., (Family Fabaceae) is a perennial flowering plant, growing as an avenue tree on roadsides. Parkinsonia flowers attracted 27 species of insects belonging to orders Hymenoptera, Diptera and Lepidoptera. They included Megachile bicolor (Fabricius), Megachile hera (Bingham), Megachile lanata (Fabricius), Megachile disjuncta (Fab.), Megachile cephalotes (Smith), Megachile badia (Fab.), Megachile semivestita (Smith), Megachile vigilans (Smith), Megachile relata (Fab.), Megachile femorata, Andrena sp., Amegilla zonata (Linnaeus), Amegilla confusa (Smith), Apis dorsata (Fab.), Apis cerana (Fab.), Apis florea (Fab.), Ceratina smaragdula (Fab.)., Xylocopa latipes (Drury), Nomia iridescens (Smith), Nomia curvipes (Fab.), and seven species of unidentified insects. Megachile bees were most abundant and constituted more than 95% of the insects visiting Parkinsonia aculeata flowers. Species diversity measured by Shannon Wiener index showed a high value of H' = 2.03, reflecting a diverse pollinator community in the area. The foragers of all the species were found to be most active between 11.00 and 15.00 hrs and the population of flower visitors declined thereafter. Information on diversity of native pollinators from disturbed habitats and their specific dependence on P. -

Annual Variation in Bee Community Structure in the Context Of

Annual Variation in Bee Community Structure in the Context of Disturbance (Niagara Region, South-Western Ontario) ~" . by Rodrigo Leon Cordero, B.Sc. A thesis submitted to the Department of Biological Sciences in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science September, 2011 Department of Biological Sciences Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © Rodrigo Leon Cordero, 2011 1 ABSTRACT This study examined annual variation in phenology, abundance and diversity of a bee community during 2003, 2004, 2006, and 2008 in rec~6vered landscapes at the southern end of St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada. Overall, 8139 individuals were collected from 26 genera and sub-genera and at least 57 species. These individuals belonged to the 5 families found in eastern North America (Andrenidae, Apidae, Colletidae, Halictidae and Megachilidae). The bee community was characterized by three distinct periods of flight activity over the four years studied (early spring, late spring/early summer, and late summer). The number of bees collected in spring was significantly higher than those collected in summer. In 2003 and 2006 abundance was higher, seasons started earlier and lasted longer than in 2004 and 2008, as a result of annual rainfall fluctuations. Differences in abundance for low and high disturbance sites decreased with years. Annual trends of generic richness resembled those detected for species. Likewise, similarity in genus and species composition decreased with time. Abundant and common taxa (13 genera and 18 species) were more persistent than rarer taxa being largely responsible for the annual fluctuations of the overall community. Numerous species were sporadic or newly introduced. The invasive species Anthidium oblongatum was first recorded in Niagara in 2006 and 2008.