CHILDREN's FOLKLORE REVIEW Editor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

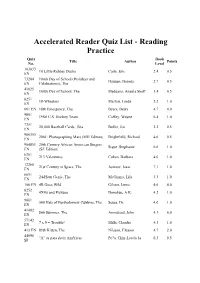

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 103833 10 Little Rubber Ducks Carle, Eric 2.4 0.5 EN 73204 100th Day of School (Holidays and Haugen, Brenda 2.7 0.5 EN Celebrations), The 41025 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 EN 8251 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda 5.2 1.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 9801 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne 6.4 1.0 EN 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 EN 900355 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edition) Brightfield, Richard 4.6 0.5 EN 904851 20th Century African American Singers Sigue, Stephanie 6.6 1.0 EN (SF Edition) 6201 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara 4.0 1.0 EN 12260 21st Century in Space, The Asimov, Isaac 7.1 1.0 EN 6651 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila 3.3 1.0 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8252 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. 4.2 1.0 EN 9001 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 EN 41482 $66 Summer, The Armistead, John 4.3 6.0 EN 57142 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 4.3 1.0 EN 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 44096 "A" es para decir Am?ricas Pe?a, Chin-Lee/de la 6.3 0.5 SP Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

PAMM Presents Cashmere Cat, Jillionaire + Special Guest Uncle Luke, a Poplife Production, During Miami Art Week in December

PAMM Presents Cashmere Cat, Jillionaire + Special Guest Uncle Luke, a Poplife Production, during Miami Art Week in December Special one-night-only performance to take place on PAMM’s Terrace Thursday, December 1, 2016 MIAMI – November 9, 2016 – Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) announces PAMM Presents Cashmere Cat, Jillionaire + special guest Uncle Luke, a Poplife Production, performance in celebration of Miami Art Week this December. Taking over PAMM’s terrace overlooking Biscayne Bay, Norwegian Musician and DJ Cashmere Cat will headline a one-night-only performance, kicking off Art Basel in Miami Beach. The show will also feature projected visual elements, set against the backdrop of the museum’s Herzog & de Meuron-designed building. The evening will continue with sets by Trinidadian DJ and music producer Jillionaire, with a special guest performance by Miami-based Luther “Uncle Luke” Campbell, an icon of Hip Hop who has enjoyed worldwide success while still being true to his Miami roots PAMM Presents Cashmere Cat, Jillionaire + special guest Uncle Luke, takes place on Thursday, December 1, 9pm–midnight, during the museum’s signature Miami Art Week/Art Basel Miami Beach celebration. The event is open to exclusively to PAMM Sustaining and above level members as well as Art Basel Miami Beach, Design Miami/ and Art Miami VIP cardholders. For more information, or to join PAMM as a Sustaining or above level member, visit pamm.org/support or contact 305 375 1709. Cashmere Cat (b. 1987, Norway) is a musical producer and DJ who has risen to fame with 30+ international headline dates including a packed out SXSW, MMW & Music Hall of Williamsburg, and recent single ‘With Me’, which premiered with Zane Lowe on BBC Radio One & video premiere at Rolling Stone. -

OF CROSSINGS and CROWDS: RE/SOUNDING SUBJECT FORMATIONS by Devon R. Kehler a Dissertation Submitted T

Of Crossings and Crowds: Re/Sounding Subject Formations Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Kehler, Devon R. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 06:11:05 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/625373 OF CROSSINGS AND CROWDS: RE/SOUNDING SUBJECT FORMATIONS by Devon R. Kehler __________________________ Copyright © Devon R. Kehler 2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN RHETORIC, COMPOSITION AND THE TEACHING OF ENGLISH In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Devon R. Kehler, titled Of Crossings and Crowds: Re/Sounding Subject Formations and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________________________________________________________ Date: April 14, 2017 Adela C. Licona ____________________________________________________________ Date: April 14, 2017 Maritza Cardenas ____________________________________________________________ Date: April 14, 2017 John Melillo Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Wedding Ringer -FULL SCRIPT W GREEN REVISIONS.Pdf

THE WEDDING RINGER FKA BEST MAN, Inc. / THE GOLDEN TUX by Jeremy Garelick & Jay Lavender GREEN REVISED - 10.22.13 YELLOW REVISED - 10.11.13 PINK REVISED - 10.1.13 BLUE REVISED - 9.17.13 WHITE SHOOTING SCRIPT - 8.27.13 Screen Gems Productions, Inc. 10202 W. Washington Blvd. Stage 6 Suite 4100 Culver City, CA 90232 GREEN REVISED 10.22.13 1 OVER BLACK A DIAL TONE...numbers DIALED...phone RINGING. SETH (V.O.) Hello? DOUG (V.O.) Oh hi, uh, Seth? SETH (V.O.) Yeah? DOUG (V.O.) It’s Doug. SETH (V.O.) Doug? Doug who? OPEN TIGHT ON DOUG Doug Harris... 30ish, on the slightly dweebier side of average. 1 REVEAL: INT. DOUG’S OFFICE - DAY 1 Organized clutter, stacks of paper cover the desk. Vintage posters/jerseys of Los Angeles sports legends adorn the walls- -ERIC DICKERSON, JIM PLUNKETT, KURT RAMBIS, STEVE GARVEY- DOUG You know, Doug Harris...Persian Rug Doug? SETH (OVER PHONE) Doug Harris! Of course. What’s up? DOUG (relieved) I know it’s been awhile, but I was calling because, I uh, have some good news...I’m getting married. SETH (OVER PHONE) That’s great. Congratulations. DOUG And, well, I was wondering if you might be interested in perhaps being my best man. GREEN REVISED 10.22.13 2 Dead silence. SETH (OVER PHONE) I have to be honest, Doug. This is kind of awkward. I mean, we don’t really know each other that well. DOUG Well...what about that weekend in Carlsbad Caverns? SETH (OVER PHONE) That was a ninth grade field trip, the whole class went. -

Daily Eastern News: March 28, 2003 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep March 2003 3-28-2003 Daily Eastern News: March 28, 2003 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2003_mar Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: March 28, 2003" (2003). March. 14. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2003_mar/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2003 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in March by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Thll the troth March28,2003 + FRIDAY and don't be afraid. • VO LUME 87 . NUMBER 123 THE DA ILYEASTERN NEWS . COM THE DAILY Four for 400 Eastern baseball team has four chances this weekend to earn head coach Jim EASTERN NEWS <:rlh....,,t n his 400th career Student fees may be hiked • Fees may raise $70 next semester By Avian Carrasquillo STUDENT GOVERNMENT ED ITOR If approved students can expect to pay an extra $70.55 in fees per semester. The Student Senate Thition and Fee Review Committee met Thursday to make its final vote on student fees for next year. Following the committee's approval, the fee proposals must be approved by the Student Senate, vice president for student affairs, the President's Council and Eastern's Board of Trustees. The largest increase of the fees will come in the network fee, which will increase to $48 per semester to fund a 10-year network improvement project. The project, which could break ground as early as this summer would upgrade the campus infra structure for network upgrades, which will Tom Akers, head coach of Eastern's track and field team, watches high jumpers during practice Thursday afternoon. -

Fast Lane by Kristen Ashley

FAST LANE BY KRISTEN ASHLEY Acknowledgments Many moons ago, I had the occasion to really listen to the song “Life in the Fast Lane” by The Eagles. I’d heard it before, tons of times. But on that listen, something struck me. Being a romantic at heart, a romance novelist and addicted to romance for as long as I can remember, that song captured me as lyrics often do. Especially if a love story is told. Any kind of love story. Even the ones without happy endings. Maybe especially ones without happy endings. So much said in a few spare lines. So many emotions welling. And as is the magic of music, on each new listen, it happens again like you’d never heard that song before. I became obsessed with it, inspired by this cautionary tale, and determined to find the right story that would fit that inspiration. It was something I thought I’d fiddle with “someday,” which is where a great number of my ideas or inspirations are relegated. Then I read Taylor Jenkins Reid’s Daisy Jones and the Six. I have never, in my life, put down a book because I was loving it so much, I had to draw it out for as long as I could. And then, weeks later, I picked it up, only begrudgingly, because I knew opening that book again would mean finishing it, and I never wanted it to end. The fresh, unique way TJR told that story as an oral history of a 70s rock band blew my mind. -

A Living Will Is Important

PRSRT STD ECRWSS U.S. Postage PAID EDDM Retail Monroe Twp., NJ 08831 VOLUME 52 / No. 8 Monroe Township, New Jersey August 2016 Focus on: Groups and Clubs Ceramics: Find your inner creator By Jean Houvener details of how to make New people are welcome at any time. The group is so- Rossmoor is fortunate to something. The group also ciable as well as talented. have a top-notch ceramics bulk purchases bisqueware The greenware, whether room with a knowledgeable (fired once) and greenware purchased, poured into and active group of partici- (already poured, but still molds, or hand built is dried pants. The room itself is raw clay) from a nearby and then fired in one of the actually several rooms, with supplier. Individuals choose kilns. The greenware, which a large work area to create and pay for what they want. is still basic clay, is fragile various types of ceramics. Because the group has until it is fired. It also needs The room is open Monday, been a good customer, the to be cleaned, with seams Wednesday, Thursday, and members get a good price. smoothed, and extra bits Saturday from 8:30 to noon. Orders are centrally made removed. Items are put on In addition to the main work through Maggie Johnsen. the “in progress” shelves to area, there is a room filled The group also does its dry and when enough with molds and forms for own creation of greenware pieces are ready, they are shaping any sort of ce- with slip pours into the fired in the kiln. -

Music & Entertainment

June 2012, Volume 130 KKaarraaookkee OOppeenn MMiicc MMuussiicc CCaalleennddaarr SSPLASHPLASH SSppllaasshheess Music & Entertainment The Voice Of Everything Fun In Hampton Roads BBeeeerr SSnnoobb SSiinnggeerr SSoonnggwwrriitteerr SShhoowwccaassee BIIEE BOOBBB B SS VVoottee FFoorr KKEE BBaarrtteennddeerr ooff tthhee EEAA MMoonntthh www.splashmag.com Later, Bobbie won the role of Macy on the soap opera, The Bold and The Beautiful, which she played over a period of 14 years and which helped her career as an international recording artist. She has two double platinum CDs and has performed in concert throughout Europe. In the U.S., she recorded a duet with country singer Collin Raye and considers singing with him at the Grand Ole Opry one of the highlights of her career. In 2003, Bobbie moved to New York to portray Krystal on the soap opera, All My Children, for which she won two Emmy nominations for Lead Actress. While in New York, she also recorded a smooth jazz CD, Something Beautiful, which debuted at number 21 on the Smooth Jazz charts. Bobbie has always contributed much of her free time promoting charitable causes. Among her favorites are Broadway Cares/Equity Fights Aids, Ahope for Children, and Desert Aids Project. She resides in Palm Springs, Calif., with her husband of 20 years, actor and writer David Steen. Crowning of The Beer Snob We at Splash would like to announce that we have finally found a suitable replacement for our illustrious Beer Snob. A true Beer Snob is not easily replaced. That is why we have been searching every bar and alcohol serving establishment in Tidewater for someone with an impeccable sense of taste and a sharp enough wit to let the rest of us in on the true beer secrets. -

Baltimore II May 7, 2021

Baltimore II May 7, 2021 - May 9, 2021 Elite 8 Junior Dancer Camdyn Fry - Arch Angel - Savage Dance Company 1st Runner-Up - Sammi Brown - Don't Rain On My Parade - Savage Dance Company Elite 8 Teen Dancer Evie Parish - Fireflies - Savage Dance Company 1st Runner-Up - Berkeley Smith - Lonely - Backstage Dance Studio 2nd Runner-Up - Nadia Gift - Hound Dog - Savage Dance Company Elite 8 Senior Dancer Lilia Butler - Candles - PDS-The Collective 1st Runner-Up - Alexis Savage - Smash - Savage Dance Company 2nd Runner-Up - Brooke Cheek - The Beginning And The End Of Everything - PDS-The Collective Top Select Petite Solo 1 - Natalie McCue - In Your Head - Savage Dance Company Top Select Junior Solo 1 - Camdyn Fry - Arch Angel - Savage Dance Company 2 - Caroline Burbage - Swagger - Seaside Dance Academy 3 - Micaiah DeRenzis - Volcanic - PDS-The Collective 4 - Madelyn Gallagher - Love Me Too - Backstage Dance Studio 5 - Sonia Kalyani - Rather Be - Backstage Dance Studio 6 - Keira Dougherty - Move - Savage Dance Company 7 - Sophia Crook - Wondering - Backstage Dance Studio 8 - Olivia Rothman - Trouble - Backstage Dance Studio 9 - Dana Judge - Wonder - Seaside Dance Academy 10 - Divya Philip - Bitter Song - Backstage Dance Studio Top Select Teen Solo 1 - Evie Parish - Fireflies - Savage Dance Company 2 - Evie Muntu - I Can Cook Too - The Movement Studios 3 - Taylor Fry - Moonlight - Savage Dance Company 4 - Berkeley Smith - Lonely - Backstage Dance Studio 5 - Nadia Gift - Hound Dog - Savage Dance Company 6 - Noelle Vesilind - Build It Up - The Movement -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Julius Caesar

BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season Brooklyn Academy of Music BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, Alan H. Fishman, and The Ohio State University present Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Julius Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Caesar Executive Producer Royal Shakespeare Company By William Shakespeare BAM Harvey Theater Apr 10—13, 16—20 & 23—27 at 7:30pm Apr 13, 20 & 27 at 2pm; Apr 14, 21 & 28 at 3pm Approximate running time: two hours and 40 minutes, including one intermission Directed by Gregory Doran Designed by Michael Vale Lighting designed by Vince Herbert Music by Akintayo Akinbode Sound designed by Jonathan Ruddick BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season sponsor: Movement by Diane Alison-Mitchell Fights by Kev McCurdy Associate director Gbolahan Obisesan BAM 2013 Theater Sponsor Julius Caesar was made possible by a generous gift from Frederick Iseman The first performance of this production took place on May 28, 2012 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Leadership support provided by The Peter Jay Stratford-upon-Avon. Sharp Foundation, Betsy & Ed Cohen / Arete Foundation, and the Hutchins Family Foundation The Royal Shakespeare Company in America is Major support for theater at BAM: presented in collaboration with The Ohio State University. The Corinthian Foundation The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation Stephanie & Timothy Ingrassia Donald R. Mullen, Jr. The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. Post-Show Talk: Members of the Royal Shakespeare Company The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund Friday, April 26. Free to same day ticket holders The SHS Foundation The Shubert Foundation, Inc. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture PLANTAE, ANIMALIA, FUNGI: TRANSFORMATIONS OF NATURAL HISTORY IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN ART A Dissertation in Art History by Alissa Walls Mazow © 2009 Alissa Walls Mazow Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2009 The Dissertation of Alissa Walls Mazow was reviewed and approved* by the following: Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Brian A. Curran Associate Professor of Art History Richard M. Doyle Professor of English, Science, Technology and Society, and Information Science and Technology Nancy Locke Associate Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract This dissertation examines the ways that five contemporary artists—Mark Dion (b. 1961), Fred Tomaselli (b. 1956), Walton Ford (b. 1960), Roxy Paine (b. 1966) and Cy Twombly (b. 1928)—have adopted the visual traditions and theoretical formulations of historical natural history to explore longstanding relationships between “nature” and “culture” and begin new dialogues about emerging paradigms, wherein plants, animals and fungi engage in ecologically-conscious dialogues. Using motifs such as curiosity cabinets and systems of taxonomy, these artists demonstrate a growing interest in the paradigms of natural history. For these practitioners natural history operates within the realm of history, memory and mythology, inspiring them to make works that examine a scientific paradigm long thought to be obsolete. This study, which itself takes on the form of a curiosity cabinet, identifies three points of consonance among these artists.