Recent Study of Raphael's Early Paintings in the National Gallery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of Shearman's Collection of Raphael Documents

BOOK REVIE'WS was inserted to make it more imrnediate, in 1936, in which most documents are not of the role previously played by Golzio) for all suggest that it was the fint scene to be published in full. monographic study, and can thereby assumea painted, and technical evidence prompts us to In the period since Shearman's book has canonical position which inhibits ftesh con- reconsider the sequence of the frescos inde- appeared the re-daring ofthe Monteluce doc- sideration of the evidence. pendendy oftheir preparation on paper. uments to r5o5, not r5o3 bp.sr-96),, and of In a moment of characteristic wit. Shear- If Raphael's contemporaries averred that Raphael's appointrnent as Sctiptor Breuium in man describes what a biography of Raphael his art was not innate but born from studying I5II, not r5og (pp.r5o-52),3have made pos- based entirely upon f).lsedocuments would 'Would be other artists, they were not totally wrong, par- sible new interpretations ofthe artist's career. like (p. r 5). he have been asamused by ticularly in regard to his early career. Raphael Sadly, however, Shearman's Corpus doesn't what a student's chronology of Raphael's life seemed to need models to emulate and sur- acfually tell us very much more about based on this publication might be like? There pass. His syncretic method, by which he Raphael than we knew already. There are would be much that was good and uncon- selected from al1 available models, painting new documents in this book (for instance, tentious, but Raphael would be said to have techniques, lighting, figure moti6, poses, those connected with Alberrinelli, supplied by been in Rome in rso2/o3; in r5o4 the only 'Signed landscape motifi, backdrops, accoutrements Louis Waldman), and it is extremely useful to entry would read and dated The Spos- and cosfumes may make him particularly have them gathered together in one place (if alizio in Citti di Castello (now Milan, Brera)',6 'gilded interesting in an age of multivalent informa- not in one volume), but we do not have the wh.ile in r5o8 Raphael would have a tron. -

This Raphael Is for Real

This Raphael is for real In the pinks: The National's Madonna. Photo: National Gallery, London For the next three months, Raphael's Madonna of the Pinks, acquired in March by the National Gallery for £22m, can be seen in our new exhibition Raphael: From Urbino to Rome, alongside 37 other paintings by the young artist. This provides an unequalled opportunity to examine the claims by Professor James Beck, reported in yesterday's Times, that this painting is not by Raphael. When a painting is as expensive as Madonna of the Pinks, it is to be expected that the gallery's decision to acquire it should be properly scrutinised. But the questions asked of the picture need to be the right ones. One person's opinion, however vociferously expressed, isn't sufficient reason to doubt a picture's authenticity. The story of the rediscovery of the painting is well known. Dr Nicholas Penny, then working at the National Gallery and the author of a major monograph on Raphael, noticed the picture on a visit to Alnwick in 1991. It had long been regarded as the best surviving copy of a lost composition by Raphael; no art historian believed it was by Raphael himself. But Penny thought it worth borrowing for examination in the gallery's scientific department. By the early 1990s, the National Gallery had recognised that a connoisseur's judgment needs to be backed up by science. Only by examining the way Raphael's painting was made could we abandon the idea that the picture was a copy. Penny found that a remarkable free drawing, very like many of Raphael's works on paper, lay under the paint. -

An Examination of a Seventeenth- Century Copy of Raphael’S Holy Family, C.1518

Uncovering the Original: An Examination of a Seventeenth- Century copy of Raphael’s Holy Family, c.1518. Annie Cornwell, Postgraduate in the Conservation of Easel Paintings Amalie Juel, MA Art History Uncovering the Original: An Examination of a 17th-Century copy of Raphael’s The Holy Family, c. 1518, The Prado Madrid. Introduction to The Project: This report has been written as part of the annual project Conservation and Art Historical Analysis, presented by the Sackler Research Forum at the Courtauld Institute of Art. Seeking to encourage collaboration between art historians and conservators, the scheme brings together two students - one from postgraduate art history and the other from easel paintings conservation - to complete an in-depth research project on a single piece of art. By doing so, the project allows a multifaceted approach combining historical research with technical analysis and, in this case, conservation treatment of the work in question. Focusing on the painting as a physical object with a material history, the project shows the value of combining art history with the more scientific aspects of the field of conservation. The focus of this project is a painting of the Virgin and Child with Saints Anne and John - a copy of Raphael’s Holy Family from the Prado - of unknown artist and date. It is owned by St Patrick’s Catholic Church in Wapping, where it had been recently found in a cupboard underneath the stairs. It came into the Courtauld Conservation Department to be treated by Annie Cornwell in November 2015, at which point it was in quite poor condition. -

The Holy Family with Saint Elizabeth

The Holy Family with Saint Elizabeth, the Child Saint John the Baptist and Two Angels, a copy of Raphael Technical report, restoration and new light on its history and attribution José de la Fuente Martínez José Luis Merino Gorospe Rocío Salas Almela Ana Sánchez-Lassa de los Santos This text is published under an international Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Creative Commons licence (BY-NC-ND), version 4.0. It may therefore be circulated, copied and reproduced (with no alteration to the contents), but for educational and research purposes only and always citing its author and provenance. It may not be used commercially. View the terms and conditions of this licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-ncnd/4.0/legalcode Using and copying images are prohibited unless expressly authorised by the owners of the photographs and/or copyright of the works. © of the texts: Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao Photography credits © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao: figs. 1, 2 and 5-19 © Groeningemuseum, Brugge: fig. 21 © Institut Royal du Patrimoine Artistique, Bruxelles: fig. 20 © Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid: fig. 55 © RMN / Gérard Blot-Jean Schormans: fig. 3 © RMN / René-Gabriel Ojéda: fig. 4 Text published in: B’06 : Buletina = Boletín = Bulletin. Bilbao : Bilboko Arte Eder Museoa = Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao = Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, no. 2, 2007, pp. 17-64. Sponsored by: 2 fter undergoing a painstaking restoration process, which included the production of a detailed tech- nical report, the Holy Family with Saint Elizabeth, the Child Saint John the Baptist and Two Angels1 A[fig. -

Peripheral Packwater Or Innovative Upland? Patterns of Franciscan Patronage in Renaissance Perugia, C.1390 - 1527

RADAR Research Archive and Digital Asset Repository Peripheral backwater or innovative upland?: patterns of Franciscan patronage in renaissance Perugia, c. 1390 - 1527 Beverley N. Lyle (2008) https://radar.brookes.ac.uk/radar/items/e2e5200e-c292-437d-a5d9-86d8ca901ae7/1/ Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, the full bibliographic details must be given as follows: Lyle, B N (2008) Peripheral backwater or innovative upland?: patterns of Franciscan patronage in renaissance Perugia, c. 1390 - 1527 PhD, Oxford Brookes University WWW.BROOKES.AC.UK/GO/RADAR Peripheral packwater or innovative upland? Patterns of Franciscan Patronage in Renaissance Perugia, c.1390 - 1527 Beverley Nicola Lyle Oxford Brookes University This work is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirelnents of Oxford Brookes University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. September 2008 1 CONTENTS Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 5 Preface 6 Chapter I: Introduction 8 Chapter 2: The Dominance of Foreign Artists (1390-c.1460) 40 Chapter 3: The Emergence of the Local School (c.1450-c.1480) 88 Chapter 4: The Supremacy of Local Painters (c.1475-c.1500) 144 Chapter 5: The Perugino Effect (1500-c.1527) 197 Chapter 6: Conclusion 245 Bibliography 256 Appendix I: i) List of Illustrations 275 ii) Illustrations 278 Appendix 2: Transcribed Documents 353 2 Abstract In 1400, Perugia had little home-grown artistic talent and relied upon foreign painters to provide its major altarpieces. -

Znanost Za Umetnost

CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 7.025.3"21"(082)(0.034.2) 7.025.4"20"(082)(0.034.2) ZNANOST za umetnost : konservatorstvo in restavratorstvo danes : zbornik prispevkov mednarodnega simpozija = Science in art : conservation and restoration today : international symposium proceedings / [znanstvena besedila Marin Berovič ... [et al.] ; glavni urednici Tamara Trček Pečak, Nada Madžarac ; prevodi iz angleščine v slovenščino Breda Misja ... [et al.], prevodi spremnih besedil Tamara Soban]. - Ljubljana : Zavod za varstvo kulturne dediščine, 2013 ISBN 978-961-6902-59-5 1. Vzp. stv. nasl. 2. Berovič, Marin 3. Trček Pečak, Tamara 270068992 Glavni urednici | Editors-in-chief Tamara Trček Pečak, Nada Madžarac Uredniški odbor | Board of editors Tina Buh, Jo Kirby, Nada Madžarac, Miladi Makuc Semion, Tamara Soban, Tamara Trček Pečak Recenzentki | Board of Reviewers: Jo Kirby, Miladi Makuc Semion Znanstvena besedila | Scientific texts Marin Berovič, Rachel Billinge, Christopher Holden, Jo Kirby, Polonca Ropret, Denis Vokić, Ulrich Weser Tuji avtorji so znanstvena besedila posredovali v angleščini, slovenska avtorja pa v obeh jezikih. All scientific texts were written in English; the Slovenian authors also provided their texts in Slovenian. Prevodi iz angleščine v slovenščino | Translations into Slovenian Breda Misja, Irena Sajovic, Tamara Soban, Suzana Stančič Prevodi spremnih besedil | Translations of introductory texts Tamara Soban Lektoriranje slovenskih besedil | Slovenian language editing Vlado Motnikar Lektoriranje angleških besedil | English language editing Jo Kirby Uredniške korekture pred tiskom | Editorial revise before printing Mateja Neža Sitar Grafično oblikovanje (2011/2012) | Graphic Design (2011/2012) Jelena Kauzlarić Izdal | Published by Zavod za varstvo kulturne dediščine Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage of Slovenia Zanj | Publishing Executive dr. -

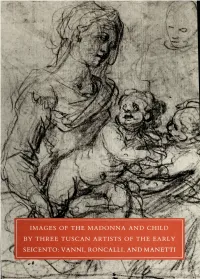

IMAGES of the MADONNA and CHILD by THREE TUSCAN ARTISTS of the EARLY SEICENTO: VANNI, RONCALLI, and MANETTI Digitized by Tine Internet Arcliive

r.^/'v/\/ f^jf ,:\J^<^^ 'Jftf IMAGES OF THE MADONNA AND CHILD BY THREE TUSCAN ARTISTS OF THE EARLY SEICENTO: VANNI, RONCALLI, AND MANETTI Digitized by tine Internet Arcliive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/innagesofmadonnacOObowd OCCASIONAL PAPERS III Images of the Madonna and Child by Three Tuscan Artists of the Early Seicento: Vanni, Roncalli, and Manetti SUSAN E. WEGNER BOWDOIN COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART BRUNSWICK, MAINE Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 86-070511 ISBN 0-91660(>-10-4 Copyright © 1986 by the President and Trustees of Bowdoin College All rights reserved Designed by Stephen Harvard Printed by Meriden-Stinehour Press Meriden, Connecticut, and Lunenburg, Vermont , Foreword The Occasional Papers of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art began in 1972 as the reincarnation of the Bulletin, a quarterly published between 1960 and 1963 which in- cluded articles about objects in the museum's collections. The first issue ofthe Occasional Papers was "The Walker Art Building Murals" by Richard V. West, then director of the museum. A second issue, "The Bowdoin Sculpture of St. John Nepomuk" by Zdenka Volavka, appeared in 1975. In this issue, Susan E. Wegner, assistant professor of art history at Bowdoin, discusses three drawings from the museum's permanent collection, all by seventeenth- century Tuscan artists. Her analysis of the style, history, and content of these three sheets adds enormously to our understanding of their origins and their interconnec- tions. Professor Wegner has given very generously of her time and knowledge in the research, writing, and editing of this article. Special recognition must also go to Susan L. -

The Marian Philatelist, Whole No. 41

University of Dayton eCommons The Marian Philatelist Marian Library Special Collections 3-1-1969 The Marian Philatelist, Whole No. 41 A. S. Horn W. J. Hoffman Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_marian_philatelist Recommended Citation Horn, A. S. and Hoffman, W. J., "The Marian Philatelist, Whole No. 41" (1969). The Marian Philatelist. 41. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_marian_philatelist/41 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Special Collections at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Marian Philatelist by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Marian Philatelist PUBLISHED BY THE MARIAN PHILATELIC STUDY GROUP Business Address: Rev. A. S. Horn Chairman 424 West Crystal View Avenue W. J. Hoffman Editor Orange, California 92667, U.S.A. Vol. 7 No. 2 Whole No. 41 MARCH 1, 1969 NEW ISSUES The original, 46-1/2 inches in diameter, is •in the Uffizi, Florence. Portion of this AJMAN: Set of 5 airmail values, with imperf work seen on the 5 Fr. value in Burundi’s sheet, designated as a "Madonna Set," released 1968 Christmas issue; see article on page November 25, 1968. Ajman is on the "tread with caution list." The designs as follows: 30 Dh. (Class 1) - MADONNA OF THE MILK (Madonna del Latte), by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, active 1319- 1348. Original is in the Church of San Frances co, Siena, Italy. 70 Dh. (Class 1) - SISTINE MADONNA by Raphael. Entire painting is seen on the December 1955 is sue of German Democratic Republic (Scott 277); detail of Madonna and Child on the May 1967 iss ue of Ecuador (see article on page 68, September 1, 1967 issue); same detail on the August 1954 issue of Saar (Scott 251) . -

J. Paul Getty Trust Press Clippings, 1954-2019 (Bulk 1983-2019), Undated

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8r215vp Online items available Finding aid for the J. Paul Getty Trust Press Clippings, 1954-2019 (bulk 1983-2019), undated Nancy Enneking, Rebecca Fenning, Kyle Morgan, and Jennifer Thompson Finding aid for the J. Paul Getty IA30017 1 Trust Press Clippings, 1954-2019 (bulk 1983-2019), undated Descriptive Summary Title: J. Paul Getty Trust press clippings Date (inclusive): 1954-2019, undated (bulk 1983-2019) Number: IA30017 Physical Description: 43.35 Linear Feet(55 boxes) Physical Description: 2.68 GB(1,954 files) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Institutional Records and Archives 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: The records comprise press clippings about the J. Paul Getty Trust, J. Paul Getty Museum, other Trust programs, and Getty family and associates, 1954-2019 (bulk 1983-2019) and undated. The records contain analog and digital files and document the extent to which the Getty was covered by various news and media outlets. Request Materials: To access physical materials at the Getty, go to the library catalog record for this collection and click "Request an Item." Click here for general library access policy . See the Administrative Information section of this finding aid for access restrictions specific to the records described below. Please note, some of the records may be stored off site; advanced notice is required for access to these materials. Language: Collection material is in English Administrative History The J. Paul Getty Trust's origins date to 1953, when J. -

Victoria Albert &Art & Love Mr Green and Mr Brown: Ludwig Grüner and Emil Braun in the Service of Prince Albert

Victoria Albert &Art & Love Mr Green and Mr Brown: Ludwig Grüner and Emil Braun in the service of Prince Albert Jonathan Marsden Essays from a study day held at the National Gallery, London on 5 and 6 June 2010 Edited by Susanna Avery-Quash Design by Tom Keates at Mick Keates Design Published by Royal Collection Trust / © HM Queen Elizabeth II 2012. Royal Collection Enterprises Limited St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1JR www.royalcollection.org ISBN 978 1905686 75 9 First published online 23/04/2012 This publication may be downloaded and printed either in its entirety or as individual chapters. It may be reproduced, and copies distributed, for non-commercial, educational purposes only. Please properly attribute the material to its respective authors. For any other uses please contact Royal Collection Enterprises Limited. www.royalcollection.org.uk Victoria Albert &Art & Love Mr Green and Mr Brown: Ludwig Grüner and Emil Braun in the service of Prince Albert Jonathan Marsden In the Introduction to his last work, The Ruins and Museums of Rome (1854), which was not only published in English but dedicated ‘To the English Visitors in Rome’, the archaeologist Emil Braun (1809–56; fig. 1) wrote of the ‘strictly German spirit’ that would be found ‘pervading’ the text: ‘The character of our [i.e. the German] education inclines us to look for that which lies beyond and above what is actually presented to us: whilst, in England, the mode of mental training is, from the first, directed exclusively upon the object itself.’ Braun went on to declare his hope that ‘the scientific treatment of art’ should be brought, ‘with the cooperation of England to the same height already attained by the natural sciences’.1 Braun was well placed to write as he did. -

Two Raphael Paintings Unearthed at the Vatican After 500 Years Published 14Th December 2017

AiA Art News-service Two Raphael paintings unearthed at the Vatican after 500 years Published 14th December 2017 Two Raphael paintings unearthed at the Vatican after 500 years Written byDelia Gallagher, CNN A 500-year-old mystery at the Vatican has just been solved. Two paintings by Renaissance master Raphael were discovered during the cleaning and restoration of a room inside the Vatican Museums. Experts believe they are his last works before an early death, around the age of 37, in 1520: "It's an amazing feeling," said the Vatican's chief restorer for the project, Fabio Piacentini. What makes Wallonia unique? "Knowing these were probably the last things he painted, you almost feel the real presence of the maestro." The two female figures, one depicting Justice and the other Friendship, were painted by Raphael around the year 1519, but he died before he could finish the rest of the room. After his death, other artists finished the wall and Raphael's two paintings were forgotten. The clues In 1508, Raphael was commissioned by Pope Julius II to paint the his private apartments. The artist completed three rooms, known today as the "Raphael rooms," with famous frescoes like the School of Athens. He then began plans for the fourth room, the largest in the apartment, a banquet hall called the Hall of Constantine. His plan was to paint the room using oil, rather than the traditional fresco technique. An ancient book from 1550 by Giorgio Vasari, "Lives of the most excellent painters, sculptors and architects," attests that Raphael began work on two figures in a new experiment with oil. -

Problem Set 5-Individual Due 2/25/09

Math & Art Problem Set 5-Individual Due 2/25/09 1. Golden Triangles: In this exercise, you will be showing that all of the triangles shown in the triangle below have the ratio long side:short side in the Golden Ratio. Since any triangles with the same angles will be similar, and hence have sides in the same proportions, this will ultimately show that any 72◦-72◦-36◦ triangle or any 36◦-36◦-108◦ triangle will be Golden, although you will of course first have to discover those angles. (Also, any isosceles triangle whose sides have this ratio will be similar to one of these twoD types.) 36 x C 72 A B 1 (a) Show that triangle ABD is similar to triangle BCA. Hints: • Since you're given that AB = AC, you know that triangle BCA is an isosceles triangle. • Remember that the base angles of an isosceles triangle are equal, and if the base angles of a triangle are equal, it's an isosceles triangle. • Although triangle ABD looks like an isosceles triangle, you are not given that it is. • Also remember that the sum of the angles in a triangle are 180◦. Sklensky Spring, 2009 Math & Art Problem Set 5-Individual Due 2/25/09 (b) Show that triangle ADC is also an isosceles triangle. (c) Use the result of part (b) to write the length BC in terms of x. (d) Use the similarity you showedp in (a), and your result to part (c), 1 + 5 to show that x = ' = . 2 (e) Show that in the isosceles triangle ADC, the ratio of the longer side to the shorter side is again '.