ZIMBABWE's 2005 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS Lessons for The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country Advice Zimbabwe Zimbabwe – ZWE36759 – Movement for Democratic Change – Returnees – Spies – Traitors – Passports – Travel Restrictions 21 June 2010

Country Advice Zimbabwe Zimbabwe – ZWE36759 – Movement for Democratic Change – Returnees – Spies – Traitors – Passports – Travel restrictions 21 June 2010 1. Deleted. 2. Deleted. 3. Please provide a general update on the situation for Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) members, both rank and file members and prominent leaders, in respect to their possible treatment and risk of serious harm in Zimbabwe. The situation for MDC members is precarious, as is borne out by the following reports which indicate that violence is perpetrated against them with impunity by Zimbabwean police and other Law and Order personnel such as the army and pro-Mugabe youth militias. Those who are deemed to be associated with the MDC party either by family ties or by employment are also adversely treated. The latest Country of Origin Information Report from the UK Home Office in December 2009 provides recent chronology of incidents from July 2009 to December 2009 where MDC members and those believed to be associated with them were adversely treated. It notes that there has been a decrease in violent incidents in some parts of the country; however, there was also a suspension of the production of the „Monthly Political Violence Reports‟ by the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum (ZHRF), so that there has not been a comprehensive accounting of incidents: POLITICALLY MOTIVATED VIOLENCE Some areas of Zimbabwe are hit harder by violence 5.06 Reporting on 30 June 2009, the Solidarity Peace Trust noted that: An uneasy calm prevails in some parts of the country, while in others tensions remain high in the wake of the horrific violence of 2008…. -

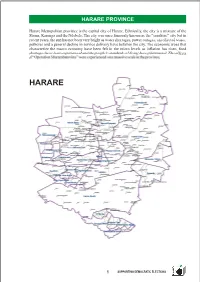

ZESN Book Final

HARARE PROVINCE The table also reveals that the number of voters per ward is higher in urban provinces than provinces that are largely rural. This is evidenced by the fact that the average number voters for Harare and Harare Metropolitan province is the capital city of Harare. Ethnically, the city is a mixture of the Bulawayo is 9826 and 10808 respectively. The average number of voters per ward for provinces that Shona, Karanga and the Ndebele. The city was once famously known as the “sunshine” city but in Constituency Profile are largely rural is less than 3000. For example, Mashonaland central has 285 wards and the average recent years, the sun has not been very bright as water shortages, power outages,HARARE uncollected PROVINCE waste, number of voters per ward is 1713. Masvingo has 242 wards and the average number of voters per potholes and a general decline in service delivery have befallen the city. The economic woes that ward is 2889. This has implications for the number of voters that will be able to cast their votes in the characterize the macro economy have been felt in the micro levels as inflation has risen, food March 29 harmonized elections. The electorate in Bulawayo and Harare provinces will experience shortages have been experienced and the people's standards of living have plummeted. The effects pressure during polls as a large number of voters have been crowded in a few wards. of “Operation Murambatsvina” were experienced on a massive scale in the province. In the 2002 presidential election, some urban voters who wished to cast their votes were not able to do as there were long queues and these discouraged voters from casting their votes. -

The Mortal Remains: Succession and the Zanu Pf Body Politic

THE MORTAL REMAINS: SUCCESSION AND THE ZANU PF BODY POLITIC Report produced for the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum by the Research and Advocacy Unit [RAU] 14th July, 2014 1 CONTENTS Page No. Foreword 3 Succession and the Constitution 5 The New Constitution 5 The genealogy of the provisions 6 The presently effective law 7 Problems with the provisions 8 The ZANU PF Party Constitution 10 The Structure of ZANU PF 10 Elected Bodies 10 Administrative and Coordinating Bodies 13 Consultative For a 16 ZANU PF Succession Process in Practice 23 The Fault Lines 23 The Military Factor 24 Early Manoeuvring 25 The Tsholotsho Saga 26 The Dissolution of the DCCs 29 The Power of the Politburo 29 The Powers of the President 30 The Congress of 2009 32 The Provincial Executive Committee Elections of 2013 34 Conclusions 45 Annexures Annexure A: Provincial Co-ordinating Committee 47 Annexure B : History of the ZANU PF Presidium 51 2 Foreword* The somewhat provocative title of this report conceals an extremely serious issue with Zimbabwean politics. The theme of succession, both of the State Presidency and the leadership of ZANU PF, increasingly bedevils all matters relating to the political stability of Zimbabwe and any form of transition to democracy. The constitutional issues related to the death (or infirmity) of the President have been dealt with in several reports by the Research and Advocacy Unit (RAU). If ZANU PF is to select the nominee to replace Robert Mugabe, as the state constitution presently requires, several problems need to be considered. The ZANU PF nominee ought to be selected in terms of the ZANU PF constitution. -

Editorial Archive July

Greek capitalism at a critical point Stamatis Karayannopoulos 2 October 2013 Greek capitalism continues to be the weak link of the Eurozone as it is still under the “intensive care” of the EU support mechanisms for the fourth consecutive year and is in recession for the sixth consecutive year. Overall GDP decline since the crisis began will reach 25% by the end of 2013 and unemployment will reach 30%. According to the Institute of Labour (INE) of the Greek General Greek General Confederation of Labour (GSEE) it will take at least 20 years to return to the pre-crisis levels! With growing rage, millions of workers, pensioners, small traders and young people who have been crushed by the austerity measures of the Memorandum are discovering what a big deception the so-called “rescue” of the country by the troika is. In reality it is a rescue of the speculators who hold the Greek debt and at the same time an attempt to avoid a domino effect of bankruptcies that could lead to the end of the Eurozone. In 2009 the Greek debt had reached 298.5 billion Euros and 128.9% of GDP. By the end of 2013, after three and a half years of such “rescue”, the debt will be 330 billion Euros and 178.5% of GDP. Up to June of this year, Greece had received 219 billion Euros from the Troika. Only 7.6 billion of this money went to towards alleviating the deficit, the rest was spent on recapitalising the banks and paying off part of the debt and the interest on the debt. -

Zimbabwe: Time for a New Approach

Zimbabwe: time for a new approach September 2011 Report of the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute (IBAHRI) Supported by the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (OSISA) This report has been compiled in accordance with the Lund – London Guidelines 2009 (www.factfindingguidelines.org) Material contained in this report may be freely quoted or reprinted, provided credit is given to the International Bar Association International Bar Association 4th Floor, 10 St Bride Street London EC4A 4AD, United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)20 7842 0090 Fax: +44 (0)20 7842 0091 Website: www.ibanet.org Contents Glossary of Acronyms 5 Executive Summary 7 Introduction 9 The mission 10 Section One: The Global Political Agreement 11 Historical background, context and results 11 Material contained in this report may be freely quoted or reprinted, provided credit is given to the International Bar Association Political participation and preparations for the next elections 15 The constitutional review process 19 Section Two: Rule Of Law 24 Independence and needs of the judiciary 24 The Attorney-General 27 Prosecutions for crimes committed in relation to the 2008 elections 29 Continuing selective application of the rule of law 30 National reconciliation 33 Zimbabwe Human Rights Commission 37 Section Three: The Extractive Industries 39 Human rights concerns 40 International Bar Association 4th Floor, 10 St Bride Street Relocation of local inhabitants from Marange to Arda Transau 41 London EC4A 4AD, United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)20 7842 0090 Fax: +44 -

Rethinking the Role of Political Economy in the Herald's

Midlands State University FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES RETHINKING THE ROLE OF POLITICAL ECONOMY IN THE HERALD’S CONSTRUCTION OF FACTIONAL FIGHTING IN ZANU-PF POST 2013 By Takunda Maodza (R124850T) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR HONOURS DEGREE IN MEDIA AND SOCIETY STUDIES GWERU, ZIMBABWE MAY 2015 RETHINKING THE ROLE OF POLITICAL ECONOMY IN THE HERALD’S CONSTRUCTION OF FACTIONAL FIGHTING IN ZANU-PF IN 2014 APPROVAL FORM The undersigned certify that they have supervised the student Takunda Maodza`s dissertation entitled: Rethinking the role of political economy in The Herald’s construction of factional fighting in Zanu-PF post 2013 submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements of Honours Degree in Media and Society Studies at Midlands State University. ………………………………… .............../.............../................ Supervisor: Z. Mugari Date ……………………………… .............../.............../................ Chairperson: Date ………………………………… .............../.............../................ External Examiner Date DECLARATION R12485OT Page i RETHINKING THE ROLE OF POLITICAL ECONOMY IN THE HERALD’S CONSTRUCTION OF FACTIONAL FIGHTING IN ZANU-PF IN 2014 I, Takunda Maodza, do hereby declare that the work contained in this dissertation is entirely my brain child with only the exception of quotations or references which have been attributed to their sources. I further declare that this work has never been previously submitted and is being submitted in partial fulfilment of Honours Degree in Media and Society Studies at Midlands State University. ………………………………… .............../.............../................ Takunda Maodza Date DEDICATION R12485OT Page ii RETHINKING THE ROLE OF POLITICAL ECONOMY IN THE HERALD’S CONSTRUCTION OF FACTIONAL FIGHTING IN ZANU-PF IN 2014 This research is dedicated to my parents Clara and Runesu Maodza for their material and moral support to my educational pursuit. -

Introduction

Introduction Introduction To the ancient question, ‘Who will guard the guardians?’ there is only one answer: those who choose the guardians. On 29 March and 27 June 2008, Zimbabwe held two historic elections. Both were ‘critical’ in the sense of defining or redefining the strategic direc- tion of the country and ensuring that it would never be the same again. Though they were different in every fundamental way, both had a pro- found effect on the tenor of national politics and firmly put the country on what appears to be an irreversible though bumpy journey towards demo- cratic transition and away from resilient authoritarianism. The 29 March elections were the first ever ‘harmonized’ elections, for the presidency, the Senate, the House of Assembly, and local government councils; they were held on one day, and results were posted at the polling stations for all to see. The 27 June election was the first presidential run- off in the country’s history and, as some of the contributions in this book will demonstrate, was also the most controversial and violent election since Independence in 1980. Elections and democracy A country’s people are the ultimate source of political legitimacy, and this is most often expressed through free elections. In the contemporary world, elections are and remain the best known and most effective device for connecting citizens to policy makers. They are a formal expression of democratic sovereignty. Paul Clarke and Joe Foweraker make a distinction between ‘thin’ and ‘fat’ conceptions of democracy and argue that the former centres on electoral democracy.1 Most such conceptions borrow from Joseph Schumpeter’s now 1 See Paul A.B. -

Dismantling the System of Mugabeism

Dismantling The System Of Mugabeism All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. ISBN 978-3-00-059482-3 First Edition © 2018 1 Dismantling The System Of Mugabeism Dedication. To my fellow Zimbabweans, we defeated Mugabe the person but Mugabeism is still intact. We must dismantle this system and bring total democratization of our country Zimbabwe. My children Lilly, Tanaka and Nkosilathi,Jr you don’t deserve to grow up in such a collapsed country which is now a shadow of itself. This is the little contribution I can make towards challenging a regime which is putting your future at stake. ‘This is the history of a failure’ (Che Guevara, The African Dream) 2 Dismantling The System Of Mugabeism Foreword. I feel refreshed and motivated to write this book in this new-old political dispensation. New in the sense that, this is the first time ever since I was born to see this country having another President who is not Robert Gabriel Mugabe and old in the sense that those who are now in power are the same people who have been in charge of this country for the past four decades working alongside Mugabe. Yes Mugabe has gone but the system he created is still intact. Are the Mnangagwas of this world going to reform and become ambassadors of peace, tolerance, democracy and respect of the rule of law? Or they will simply pick up the sjamboks from where Mugabe left them and perpetuate his legacy of brutality? Is corruption going to end considering that a few former Ministers who were arrested by Mnangagwa’s administration were being used as scapegoats, most of the criminals and kleptocrats who committed serious crimes against humanity and corruption are still serving in the post-Mugabe ZANU PF government? The same old people who bled Zimbabwe dry serving in the kleptocratic regime of Robert Mugabe are the same people who are serving under Mnangagwa. -

MISA-Zimbabwe

MISA-Zimbabwe The Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act: Two Years On ARTICLE 19/MISA-ZIMBABWE ARTICLE 19, London and MISA-Zimbabwe, Harare ISBN [TO BE ADDED] September 2004 ARTICLE 19, 33 Islington High St., London N1 9LH • Tel. +44 20 7278 9292 • [email protected] • www.article19.org MISA-Zimbabwe, 84 McChlery Avenue Eastlea, P O Box HR 8113 Harare • Tel: (263 4) 776 165/746 838, mobile: (263) 11 602 685, • [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Report was prepared jointly by Toby Mendel, Law Programme Director, ARTICLE 19, and Rashweat Mukundu, MISA-Zimbabwe. It was copy edited by Pauline Donaldson, Campaign and Development Team, ARTICLE 19. ARTICLE 19 and MISA-Zimbabwe would like to thank the Open Society Institute Justice Initiative for its financial support for the development and publication of this Report. The positions taken in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of the Open Society Institute Justice Initiative. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 1 II. AIPPA: OVERVIEW AND CRITIQUE ........................................ 3 II.1 FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ........................................................................... 4 II.2 THE MEDIA AND INFORMATION COMMISSION.............................................. 6 II.3 REGISTRATION OF THE MASS MEDIA ............................................................. 7 II.4 ACCREDITATION OF JOURNALISTS.................................................................. 9 II.5 CONTENT -

Land and Agrarian Reform in Former Settler Colonial Zimbabwe.Indd

3 A Decade of Zimbabwe’s Land Revolution: The Politics of the War Veteran Vanguard Zvakanyorwa Wilbert Sadomba Introduction The Zimbabwe state, governed since 1980 by a nationalist elite with origins in the liberation movement, has experienced complex dynamics and changes regarding class relations and power in a post-colonial settler economy. The state reached a climax of political polarisation during this last decade, from 2000 to 2010. In the first two decades of independence, the ruling nationalist class had enjoyed an alliance with settler capital forged during peace negotiations in 1979 at Lancaster House (see Horne 20011 and Selby 2006). The alliance antagonised and negated the aspirations of the liberation struggle expressed symbolically and concretely in terms of reversing a century old grievance over unequal colonial land ownership structures. War veterans were an ‘embodiment’ of this anti-colonial demand (Kriger 1995), although a scattered peasant movement had dominated land struggles until 1996 (see Moyo 2001). These war veterans, as a social category, were constituted by a movement of former military youth and so-called former refugees, whose nucleus were fighters of the Zimbabwe’s liberation war2. The conflict between the neocolonial state on the one hand and peasants and war veterans, on the other, intensified during the 1990s. The state had successfully managed to suppress the organisation of war veterans during the 1980s. However, in 1997, it conceded to provide for their welfare and financial demands and, LLandand aandnd AAgrariangrarian RReformeform iinn FFormerormer SSettlerettler CColonialolonial ZZimbabwe.inddimbabwe.indd 7799 228/03/20138/03/2013 112:40:392:40:39 80 Land and Agrarian Reform in Zimbabwe: Beyond White-Settler Capitalism as part of the conditions of a truce entered between war veterans and President Robert Mugabe, promised to redistribute land. -

Civil Society, the State and Democracy in Zimbabwe, 1988 –

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012) Title of the thesis or dissertation. PhD. (Chemistry)/ M.Sc. (Physics)/ M.A. (Philosophy)/M.Com. (Finance) etc. [Unpublished]: University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from: https://ujcontent.uj.ac.za/vital/access/manager/Index?site_name=Research%20Output (Accessed: Date). CIVIL SOCIETY, THE STATE AND DEMOCRACY IN ZIMBABWE, 1988 – 2014: HEGEMONIES, POLARITIES AND FRACTURES By ZENZO MOYO A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, University of Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Literature and Philosophy in Development Studies Supervisor: Professor David Moore August 2018 Declaration of originality I declare that Civil Society, the State and Democracy in Zimbabwe, 1988 – 2014: Hegemonies, Polarities and Fractures is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. Zenzo Moyo (Researcher) Signed: …… …… Date…23 July 2018…… ii ABSTRACT The post-independence ruling class in Zimbabwe carefully combined coercion and consent to assert its hegemony from the day it assumed state power. It implemented this through making use of both civil society and political society. -

The Real Change Times Movement for Democratic Change a Party of Excellence! the Official Mouthpiece of the MDC

Iz qula enzo u I G ze o n ir z it o a G M u q a j u n l i a h C C h o i r n i t j i a a M M a a i j t i n r i o h C The Real Change Times Movement for Democratic Change A Party of Excellence! The Official Mouthpiece of the MDC Tuesday 26 June MDC Information & Publicity Department, Harvest House, 44 Nelson Mandela Ave, Harare, Zimbabwe Issue 112 2012 MDC not formed to fight army The MDC was formed to fight Zanu PF formed to fight the army; it was formed who was one of the election observers and not the army, a parliamentarian said to contest Zanu PF,” he added. in Malawi’s first ever democratic last week. election in the early 1990s said people Hon Chitando explained that the must differentiate between transfer of Masvingo Central Member of the introduction of the motion was power and transitional process. House of Assembly, Hon Jeffreyson motivated by the fact that Zimbabwe Chitando said this when he introduced will hold elections within a year and “I would like to emphasise on the a motion to deal with pre and post- the manifestations of violence already transfer of power which would happen election transition. emerging in the country. where the winner is declared and the loser acknowledges the election; that is Hon Chitando’s call comes in the wake Before the start of the debate, during transfer of power. of peaceful power transition in Zambia, the Prime Minister’s Question and Malawi, Senegal and Lesotho.