Cuneiform Tablets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Financial Assistance Policy FINAL Cape Verdean.Pdf

Apolisi #: 08.26.001 Revizadu: 04/2020 Revizadu: 11/2020 Sekson: Finansa Asistênsia Finanseru pa Pasientis. Obijêtivu: Sentru di Saúdi di Boston, (Hospital ô BMC), dizinvolvi kel pulitika li pa identifika i ajuda pisoas elijivel ku baxu-rendimentu, sên sigúru i sên sigúru-sufisienti, ku inskrison na planus di sigúru di saúdi ô prugramas di asistênsia finanseru pa kubri gastus di servisus di saúdi i sigura asesu a tempu i apropriadu a kuidadus medikamentti nisisariu. Grupu Mediku Universitáriu di Boston, (BUMG), komu un parséru kolaborador di BMC, sta di akordu a aderi orientasons istabilisidus aprizentadu na Pulitika di Asistênsia Finanseru di Hospital. Diklarason di Pulitika: É pulitika di BMC, en parseria ku sés sentrus di saúdi komunitarius lisensiadus, fornêsi kuidadus medikus nisisarius a tudu pasientis, indipendentimenti di si kapasidadi di paga, i oferêsi asistênsia finanseru pa kés ki ka tên sigúru ô ki tên sigúru insufisienti i ki ka ta podi paga. Tudu pasientis ki parsi na BMC i mesti servisus imirjentis ô urjentis, ô otu servisu mediku nisisariu, debi ser tratadu indipendentimenti di rasa, kor, rilijion, krensa, sexu, nasionalidadi, idadi, difisênsia, identidadi ô ixpreson di jêneru, kapasidadi pa paga. BMC ta oferêsi asistênsia finanseru pa tudu pasientis di baxu-rendimentu, sên sigúru ô ku sigúru insufisienti, ki ta dimostra falta di kapasidadi di paga pa tudu, ô algun parti di kobransas kê debi. Pasientis sên kapasidadi finanseru pa paga ta ser selesionadu pa elijibilidadi ku Medcaid ô otus prugramas istadual, Planus di Saúdi Kualifikavel, ô és ta ser avaliadu di akordu ku orientasons pre-istabilisidu pa ditermina elijibilidadi pa asistênsia na prugrama di Benifisênsia di Servisus di Hospital (CCP). -

Sumerian Lexicon, Version 3.0 1 A

Sumerian Lexicon Version 3.0 by John A. Halloran The following lexicon contains 1,255 Sumerian logogram words and 2,511 Sumerian compound words. A logogram is a reading of a cuneiform sign which represents a word in the spoken language. Sumerian scribes invented the practice of writing in cuneiform on clay tablets sometime around 3400 B.C. in the Uruk/Warka region of southern Iraq. The language that they spoke, Sumerian, is known to us through a large body of texts and through bilingual cuneiform dictionaries of Sumerian and Akkadian, the language of their Semitic successors, to which Sumerian is not related. These bilingual dictionaries date from the Old Babylonian period (1800-1600 B.C.), by which time Sumerian had ceased to be spoken, except by the scribes. The earliest and most important words in Sumerian had their own cuneiform signs, whose origins were pictographic, making an initial repertoire of about a thousand signs or logograms. Beyond these words, two-thirds of this lexicon now consists of words that are transparent compounds of separate logogram words. I have greatly expanded the section containing compounds in this version, but I know that many more compound words could be added. Many cuneiform signs can be pronounced in more than one way and often two or more signs share the same pronunciation, in which case it is necessary to indicate in the transliteration which cuneiform sign is meant; Assyriologists have developed a system whereby the second homophone is marked by an acute accent (´), the third homophone by a grave accent (`), and the remainder by subscript numerals. -

Cyrus the Great As a “King of the City of Anshan”*

ANTIGONI ZOURNATZI Cyrus the Great as a “King of the City of Anshan”* The Anshanite dynastic title of Cyrus the Great and current interpretations Since its discovery in the ruins of Babylon in 1879, the inscribed Cylinder of Cyrus the Great (fig. 1)1 has had a powerful impact on modern perceptions of the founder of the Persian empire. Composed following Cyrus’ conquest of Babylon in 539 BC and stressing above all his care for the Babylonian people and his acts of social and religious restoration, the Akkadian text of the Cylin- der occupies a central place in modern discussions of Cyrus’ imperial policy.2 This famous document is also at the heart of a lively scholarly controversy concerning the background of Cyrus’ dynastic line. The Persian monarch Darius I –who rose to the throne approximately a decade after the death of Cyrus the Great and who founded the ruling dynasty * This paper was initially presented in the First International Conference Iran and the Silk Road (National Museum of Iran, 12-14 February 2011). A pre-publication ver- sion was kindly hosted by Pierre Briant on Achemenet (Zournatzi 2011, prompting the similar reflections of Stronach 2013). The author wishes to express her appreciation to Daryoosh Akbarzadeh and the other organizers of the Tehran conference for the opportunity to participate in a meeting that opened up important new vistas on the complex interactions along the paths of the Silk Road, for their hospitality, as well as for their most gracious permission for both the preliminary and the present final publication. Thanks are equally due to Judith Lerner for a useful discussion concerning the possible wider currency of Cyrus’ Anshanite title outside the Babylonian domain, and to Michael Roaf, David Stronach, and the two reviewers of the article for helpful comments and bibliographical references. -

Baseandmodifiedcuneiformsigns.Pdf

12000 CUNEIFORM SIGN A 12001 CUNEIFORM SIGN A TIMES A 12002 CUNEIFORM SIGN A TIMES BAD 12003 CUNEIFORM SIGN A TIMES GAN2 TENU 12004 CUNEIFORM SIGN A TIMES HA 12005 CUNEIFORM SIGN A TIMES IGI 12006 CUNEIFORM SIGN A TIMES LAGAR GUNU 12007 CUNEIFORM SIGN A TIMES MUSH 12008 CUNEIFORM SIGN A TIMES SAG 12009 CUNEIFORM SIGN A2 1200A CUNEIFORM SIGN AB 1200B CUNEIFORM SIGN AB GUNU 1200C CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES ASH2 1200D CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES GIN2 1200E CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES GAL 1200F CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES GAN2 TENU 12010 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES HA 12011 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES IMIN 12012 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES LAGAB 12013 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES SHESH 12014 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES SIG7 12015 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES U PLUS U PLUS U 12016 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 12017 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES ASHGAB 12018 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES BALAG 12019 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES BI 1201A CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES DUG 1201B CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES GAN2 TENU 1201C CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES GUD 1201D CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES KAD3 1201E CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES LA 1201F CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES ME PLUS EN 12020 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES NE 12021 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES SHA3 12022 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES SIG7 12023 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES SILA3 12024 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES TAK4 12025 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES U2 12026 CUNEIFORM SIGN AD 12027 CUNEIFORM SIGN AK 12028 CUNEIFORM SIGN AK TIMES ERIN2 12029 CUNEIFORM SIGN AK TIMES SAL PLUS GISH 1202A CUNEIFORM SIGN AK TIMES SHITA PLUS GISH 1202B CUNEIFORM SIGN AL 1202C CUNEIFORM SIGN -

Trinity College Bulletin, 1941-1942 (Necrology)

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Trinity College Bulletins and Catalogues (1824 - Trinity Publications (Newspapers, Yearbooks, present) Catalogs, etc.) 7-1-1942 Trinity College Bulletin, 1941-1942 (Necrology) Trinity College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/bulletin Recommended Citation Trinity College, "Trinity College Bulletin, 1941-1942 (Necrology)" (1942). Trinity College Bulletins and Catalogues (1824 - present). 126. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/bulletin/126 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Trinity Publications (Newspapers, Yearbooks, Catalogs, etc.) at Trinity College Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trinity College Bulletins and Catalogues (1824 - present) by an authorized administrator of Trinity College Digital Repository. OLUME XXXIX NEW SERIES NUMBER 3 Wriutty <trnllrgr iullrtiu NECROLOGY Jlartforb, C!tounrdtrut July, 1942 Trinity College Bulletin Issued quarterly by the College. Entered January 12, 1904, at Hartford, Conn., as second class matter under the Act of Congress of July 16, 1894. Accepted for mailing at special rate of postage provided for in Section 1103, A ct of October 3, 1917, authorized March J, 1919. The Bulletin includes in its issues: The College Catalogue; Reports of the President. Treasurer. Dean. and Librarian; Announcements, Necrology, and Circulars of Information. NECROLOGY TRINITY MEN Whose deaths were reported during the year 1941-1942 Hartford, Connecticut July, 1942 PREFATORY NOTE This Obituary Record is the twenty-second issued, the plan of devoting the July issue of the Bulletin to this use having been adopted in 1918. The data here presented have ·been collected through the persistent efforts of the Treasurer's Office, _which makes every effort to secure and preserve as full a record as possible of the activities of Trinity men as well as anything else . -

Cuneiform Luvian Lexicon in Anticipation of a New Edition

Notice I have suspended sales of the print version of my Cuneiform Luvian Lexicon in anticipation of a new edition. Since appearance of the latter has been delayed, I am making this online version available. I hereby expressly give consent for it to be printed and further reproduced without charge. The work remains copyrighted and should be cited as such. I stress especially that the present version is an unrevised reproduction of the original 1993 work (with only obvious typographical errors removed and the two bibliographical items listed as “to appear” now given in full). Anything contained herein should be cited as “1993”! Preparation of the pdf version from what is already an archaic original computerized text involved a threefold conversion. Some formatting errors have surely been introduced that I have failed to notice and correct. I would be grateful if users would point these out to me by e-mail ([email protected]). H. Craig Melchert July, 2001 LEXICA ANATOLICA VOLUME 2 CUNEIFORM LUVIAN LEXICON H. CRAIG MELCHERT Chapel Hill, N.C. 1993 Copyright c 1993. All rights reserved FOREWORD Like its predecessor, this lexicon has a very modest aim: to furnish a provisional index, as exhaustive as possible, of all attested Cuneiform Luvian lexemes. It is intended to be complete for the CLuvian corpus as established by Frank Starke, Die keilschrift-luwischen Texte in Umschrift (StBoT 30), Wiesbaden: 1985 (with the addenda and corrigenda in StBoT 31 (1990) 592-607). I have followed Starke's readings unless explicitly noted otherwise. The coverage of Luvianisms and Luvian loanwords in Hittite contexts is necessarily selective: see further below. -

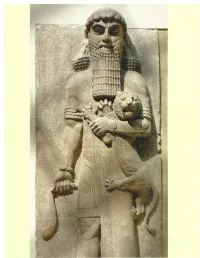

The Epic of Gilgamesh

Semantikon.com presents An Old Babylonian Version of the Gilgamesh Epic On the Basis of Recently Discovered Texts By Morris Jastrow Jr., Ph.D., LL.D. Professor of Semitic Languages, University of Pennsylvania And Albert T. Clay, Ph.D., LL.D., Litt.D. Professor of Assyriology and Babylonian Literature, Yale University In Memory of William Max Müller (1863-1919) Whose life was devoted to Egyptological research which he greatly enriched by many contributions PREFATORY NOTE The Introduction, the Commentary to the two tablets, and the Appendix, are by Professor Jastrow, and for these he assumes the sole responsibility. The text of the Yale tablet is by Professor Clay. The transliteration and the translation of the two tablets represent the joint work of the two authors. In the transliteration of the two tablets, C. E. Keiser's "System of Accentuation for Sumero-Akkadian signs" (Yale Oriental Researches--VOL. IX, Appendix, New Haven, 1919) has been followed. INTRODUCTION. I. The Gilgamesh Epic is the most notable literary product of Babylonia as yet discovered in the mounds of Mesopotamia. It recounts the exploits and adventures of a favorite hero, and in its final form covers twelve tablets, each tablet consisting of six columns (three on the obverse and three on the reverse) of about 50 lines for each column, or a total of about 3600 lines. Of this total, however, barely more than one-half has been found among the remains of the great collection of cuneiform tablets gathered by King Ashurbanapal (668-626 B.C.) in his palace at Nineveh, and discovered by Layard in 1854 [1] in the course of his excavations of the mound Kouyunjik (opposite Mosul). -

Sumerian Liturgical Texts

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA THE UNIVERSITY MUSEUM PUBLICATIONS OF THE BABYLONIAN SECTION VOL. X No. 2 SUMERIAN LITURGICAL TEXTS BY g600@T STEPHEN LANGDON ,.!, ' PHILADELPHIA PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY MUSEUM 1917 DIVINITY LIBRARY gJ-37 . f's- ". /o, ,7'Y,.'j' CONTENTS INTRODUC1'ION ................................... SUMERIAN LITURGICAL TEXTS: EPICALPOEM ON THE ORIGINOF SLIMERIANCIVILI- ZATION ...................................... LAMENTATIONTO ARURU......................... PENITENTIALPSALM TO GOD AMURRU............. LAMENTATIONON THE INVASION BY GUTIUM....... LEGENDOF GILGAMISH........................... LITURGICALHYMN TO UR-ENGUR............. .. .. LITURGICALHYMN TO DUNGI...................... LITURGICALHYMN TO LIBIT-ISHTAR(?)OR ISHME- DAGAN(?)................................... LITURGICALHYMN TO ISHME-DAGAN............... LAMENTATIONON THE DESTRUCTIONOF UR ........ HYMNOF SAMSUILUNA........................... LITURGYTO ENLIL.babbar-ri babbar.ri.gim. INCLUD- ING A TRANSLATIONOF SBH 39 .............. FRAGMENTFROM THE TITULARLITANY OF A LITURGY LITURGICALHYMN TO ISHME.DAGAN............... LITURGYTO INNINI ............................... INTRODUCTION Under the title SUMERIANLITURGICAL TEXTS the author has collected the material of the Nippur collection which belonged to the various public song services of the Sumerian and Babylonian temples. In this category he has included the epical and theological poems called lag-sal. These long epical compositions are the work of a group of scholars at Nippur who ambitiously planned to write a series -

The Achaemenid Empire in South Asia and Recent Excavations in Akra in Northwest Pakistan Peter Magee Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology Faculty Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology Research and Scholarship 2005 The Achaemenid Empire in South Asia and Recent Excavations in Akra in Northwest Pakistan Peter Magee Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Cameron Petrie Robert Knox Farid Khan Ken Thomas Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/arch_pubs Part of the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Custom Citation Magee, Peter, Cameron Petrie, Richard Knox, Farid Khan, and Ken Thomas. 2005. The Achaemenid Empire in South Asia and Recent Excavations in Akra in Northwest Pakistan. American Journal of Archaeology 109:711-741. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/arch_pubs/82 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Achaemenid Empire in South Asia and Recent Excavations in Akra in Northwest Pakistan PETER MAGEE, CAMERON PETRIE, ROBERT KNOX, FARID KHAN, AND KEN THOMAS Abstract subject peoples. A significant proportion of this The impact of the Achaemenid annexation of north- research has been carried out on the regions that westernPakistan has remained a focus for archaeological border the classical world, in particular Anatolia,1 researchfor more than a century.A lack of well-stratified the Levant,2and Egypt.3In contrast, the far eastern settlementsand a focus on artifactsthat are not necessar- extent of the which is the for the effects of control empire, encompassed by ily appropriate assessing imperial borders of Pakistan and haveuntil now obfuscatedour understandingof this issue. -

Archaeology of Mesopotamia Syllabus

AE0037 Archaeology of Mesopotamia Fall 2006 Artemis A.W. and Martha Sharp Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World Brown University Syllabus MWF 12:00-12:50 (The so-called E-hour) Salomon Center Room 203 Instructor: Ömür Harmansah (Visiting Assistant Professor) Office Hours: Tuesday 10-12 am. (Or by appointment) Office: Joukowsky Institute (70 Waterman St.) Room 202 E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 401-863-6411 Course website where the up-to-date syllabus can be downloaded: http://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/Harmansah/teach.html Course Description This course offers an analytical survey of the social and cultural history of the Near East, tracing the variety of cultural developments in the region from prehistory to the end of the Iron age (ca. 300 BC). Both archaeological evidence and textual sources are examined as relevant. The material culture and social practices of Mesopotamian societies constitute the main focus of the course. Archaeological landscapes, urban and rural sites, excavated architectural remains and artifacts are critically investigated based on archaeological, anthropological and art-historical work carried out in the region. Relevant ancient texts (mostly in Sumerian, Akkadian, and Luwian in translation) are studied as part of the material culture. Geographically the course will cover Mesopotamia proper, Syria, Anatolia and the Levantine coast (mostly staying within the boundaries of modern-day Iraq, Syria, and Turkey). In order to study the material evidence from antiquity critically, scholars frequently involve interpretive theories in their work. Throughout the semester, along with the detailed reading of various bodies of archaeological evidence, we will investigate a variety of theoretical approaches and concepts used within the field of Near Eastern archaeology. -

Guide, George Aaron Barton Papers (UPT 50 B293)

A Guide to the George Aaron Barton Papers 1903-1942 2.0 Cubic feet UPT 50 B293 Prepared by Denise Piezynski under the direction of Theresa R. Snyder November 1989 The University Archives and Records Center 3401 Market Street, Suite 210 Philadelphia, PA 19104-3358 215.898.7024 Fax: 215.573.2036 www.archives.upenn.edu Mark Frazier Lloyd, Director George Aaron Barton Papers UPT 50 B293 TABLE OF CONTENTS PROVENANCE...............................................................................................................................1 ARRANGEMENT...........................................................................................................................1 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE................................................................................................................1 SCOPE AND CONTENT...............................................................................................................2 CONTROLLED ACCESS HEADINGS.........................................................................................3 INVENTORY.................................................................................................................................. 4 PERSONAL PAPERS...............................................................................................................4 MANUSCRIPTS....................................................................................................................... 6 George Aaron Barton Papers UPT 50 B293 Guide to the George Aaron Barton Papers 1903-1942 UPT 50 B293 -

Mesopotamian Society Was a Man the TRANSITION Named Gilgamesh

y far, the most familiar individual of ancient Mesopotamian society was a man THE TRANSITION named Gilgamesh. According to historical sources, Gilgamesh was the fifth TO AGRICULTURE king of the city of Uruk. He ruled about 2750 B.C. E., and he led his community The Paleolithic Era in its conflicts with Kish, a nearby city that was the principal rival of Uruk. The Neolithic Era Gilgamesh was a figure of Mesopotamian mythology and folklore as well as his tory. He was the subject of numerous poems and legends, and Mesopotamian bards THE QUEST FOR ORDER made him the central figure in a cycle of stories known collectively as the Epic of Mesopotamia: "The Land Gilgamesh. As a figure of legend, Gilgamesh became the greatest hero figure of between the Rivers" ancient Mesopotamia. According to the stories, the gods granted Gilgamesh a per The Course of Empire fect body and endowed him with superhuman strength and courage. The legends declare that he constructed the massive city walls of Uruk as well as several of the THE FORMATION OF A COMPLEX SOCIETY city's magnificent temples to Mesopotamian deities. AND SOPHISTICATED The stories that make up the Epic of Gi/gamesh recount the adventures of this CULTURAL TRADITIONS hero and his cherished friend Enkidu as they sought fame. They killed an evil mon Economic Specialization ster, rescued Uruk from a ravaging bull, and matched wits with the gods. In spite of and Trade their heroic deeds, Enkidu offended the gods and fell under a sentence of death. The Emergence of a His loss profoundly affected Gilgamesh, who sought The Epic of Gilgamesh Stratified Patriarchal Society for some means to cheat death and gain eternal www.mhhe.com/ • bentleybrief2e The Development of Written life.