Within the Framework of the Synchronic Attitude to the Book Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sumerian Lexicon, Version 3.0 1 A

Sumerian Lexicon Version 3.0 by John A. Halloran The following lexicon contains 1,255 Sumerian logogram words and 2,511 Sumerian compound words. A logogram is a reading of a cuneiform sign which represents a word in the spoken language. Sumerian scribes invented the practice of writing in cuneiform on clay tablets sometime around 3400 B.C. in the Uruk/Warka region of southern Iraq. The language that they spoke, Sumerian, is known to us through a large body of texts and through bilingual cuneiform dictionaries of Sumerian and Akkadian, the language of their Semitic successors, to which Sumerian is not related. These bilingual dictionaries date from the Old Babylonian period (1800-1600 B.C.), by which time Sumerian had ceased to be spoken, except by the scribes. The earliest and most important words in Sumerian had their own cuneiform signs, whose origins were pictographic, making an initial repertoire of about a thousand signs or logograms. Beyond these words, two-thirds of this lexicon now consists of words that are transparent compounds of separate logogram words. I have greatly expanded the section containing compounds in this version, but I know that many more compound words could be added. Many cuneiform signs can be pronounced in more than one way and often two or more signs share the same pronunciation, in which case it is necessary to indicate in the transliteration which cuneiform sign is meant; Assyriologists have developed a system whereby the second homophone is marked by an acute accent (´), the third homophone by a grave accent (`), and the remainder by subscript numerals. -

Baseandmodifiedcuneiformsigns.Pdf

12000 CUNEIFORM SIGN A 12001 CUNEIFORM SIGN A TIMES A 12002 CUNEIFORM SIGN A TIMES BAD 12003 CUNEIFORM SIGN A TIMES GAN2 TENU 12004 CUNEIFORM SIGN A TIMES HA 12005 CUNEIFORM SIGN A TIMES IGI 12006 CUNEIFORM SIGN A TIMES LAGAR GUNU 12007 CUNEIFORM SIGN A TIMES MUSH 12008 CUNEIFORM SIGN A TIMES SAG 12009 CUNEIFORM SIGN A2 1200A CUNEIFORM SIGN AB 1200B CUNEIFORM SIGN AB GUNU 1200C CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES ASH2 1200D CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES GIN2 1200E CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES GAL 1200F CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES GAN2 TENU 12010 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES HA 12011 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES IMIN 12012 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES LAGAB 12013 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES SHESH 12014 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES SIG7 12015 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB TIMES U PLUS U PLUS U 12016 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 12017 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES ASHGAB 12018 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES BALAG 12019 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES BI 1201A CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES DUG 1201B CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES GAN2 TENU 1201C CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES GUD 1201D CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES KAD3 1201E CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES LA 1201F CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES ME PLUS EN 12020 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES NE 12021 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES SHA3 12022 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES SIG7 12023 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES SILA3 12024 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES TAK4 12025 CUNEIFORM SIGN AB2 TIMES U2 12026 CUNEIFORM SIGN AD 12027 CUNEIFORM SIGN AK 12028 CUNEIFORM SIGN AK TIMES ERIN2 12029 CUNEIFORM SIGN AK TIMES SAL PLUS GISH 1202A CUNEIFORM SIGN AK TIMES SHITA PLUS GISH 1202B CUNEIFORM SIGN AL 1202C CUNEIFORM SIGN -

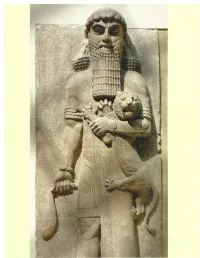

Mesopotamian Society Was a Man the TRANSITION Named Gilgamesh

y far, the most familiar individual of ancient Mesopotamian society was a man THE TRANSITION named Gilgamesh. According to historical sources, Gilgamesh was the fifth TO AGRICULTURE king of the city of Uruk. He ruled about 2750 B.C. E., and he led his community The Paleolithic Era in its conflicts with Kish, a nearby city that was the principal rival of Uruk. The Neolithic Era Gilgamesh was a figure of Mesopotamian mythology and folklore as well as his tory. He was the subject of numerous poems and legends, and Mesopotamian bards THE QUEST FOR ORDER made him the central figure in a cycle of stories known collectively as the Epic of Mesopotamia: "The Land Gilgamesh. As a figure of legend, Gilgamesh became the greatest hero figure of between the Rivers" ancient Mesopotamia. According to the stories, the gods granted Gilgamesh a per The Course of Empire fect body and endowed him with superhuman strength and courage. The legends declare that he constructed the massive city walls of Uruk as well as several of the THE FORMATION OF A COMPLEX SOCIETY city's magnificent temples to Mesopotamian deities. AND SOPHISTICATED The stories that make up the Epic of Gi/gamesh recount the adventures of this CULTURAL TRADITIONS hero and his cherished friend Enkidu as they sought fame. They killed an evil mon Economic Specialization ster, rescued Uruk from a ravaging bull, and matched wits with the gods. In spite of and Trade their heroic deeds, Enkidu offended the gods and fell under a sentence of death. The Emergence of a His loss profoundly affected Gilgamesh, who sought The Epic of Gilgamesh Stratified Patriarchal Society for some means to cheat death and gain eternal www.mhhe.com/ • bentleybrief2e The Development of Written life. -

The Old Testament in the Light of the Historical Records and Legends of Assyria and Babylonia by Theophilus Goldridge Pinches

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Old Testament In the Light of The Historical Records and Legends of Assyria and Babylonia by Theophilus Goldridge Pinches This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Old Testament In the Light of The Historical Records and Legends of Assyria and Babylonia Author: Theophilus Goldridge Pinches Release Date: January 31, 2012 [Ebook 38732] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE OLD TESTAMENT IN THE LIGHT OF THE HISTORICAL RECORDS AND LEGENDS OF ASSYRIA AND BABYLONIA*** The Old Testament In the Light of The Historical Records and Legends of Assyria and Babylonia By Theophilus G. Pinches LL.D., M.R.A.S. Published under the direction of the Tract Committee Third Edition—Revised, With Appendices and Notes London: Society For Promoting Christian Knowledge 1908 Contents Foreword . .2 Chapter I. The Early Traditions Of The Creation. .5 Chapter II. The History, As Given In The Bible, From The Creation To The Flood. 63 Chapter III. The Flood. 80 Appendix. The Second Version Of The Flood-Story. 109 Chapter IV. Assyria, Babylonia, And The Hebrews, With Reference To The So-Called Genealogical Table. 111 The Tower Of Babel. 123 The Patriarchs To Abraham. 132 Chapter V. Babylonia At The Time Of Abraham. 143 The Religious Element. 152 The King. 156 The People. -

OLD AKKADIAN WRITING and GRAMMAR Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu OLD AKKADIAN WRITING AND GRAMMAR oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu MATERIALS FOR THE ASSYRIAN DICTIONARY NO. 2 OLD AKKADIAN WRITING AND GRAMMAR BY I. J. GELB SECOND EDITION, REVISED and ENLARGED THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada c, 1952 and 1961 by The University of Chicago. Published 1952. Second Edition Published 1961. PHOTOLITHOPRINTED BY GUSHING - MALLOY, INC. ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 1961 oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS pages I. INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY OF OLD AKKADIAN 1-19 A. Definition of Old Akkadian 1. B. Pre-Sargonic Sources 1 C. Sargonic Sources 6 D. Ur III Sources 16 II. OLD AKKADIAN WRITING 20-118 A. Logograms 20 B. Syllabo grams 23 1. Writing of Vowels, "Weak" Consonants, and the Like 24 2. Writing of Stops and Sibilants 28 3. General Remarks 4o C. Auxiliary Marks 43 D. Signs 45 E. Syllabary 46 III. GRAMMAR OF OLD AKKADIAN 119-192 A. Phonology 119 1. Consonants 119 2. Semi-vowels 122 3. Vowels and Diphthongs 123 B. Pronouns 127 1. Personal Pronouns 127 a. Independent 127 b. Suffixal 128 i. With Nouns 128 ii. With Verbs 130 2. Demonstrative Pronouns 132 3. 'Determinative-Relative-Indefinite Pronouns 133 4. Comparative Discussion 134 5. Possessive Pronoun 136 6. Interrogative Pronouns 136 7. Indefinite Pronoun 137 oi.uchicago.edu pages C. Nouns 137 1. Declension 137 a. Gender 137 b. Number 138 c. Case Endings- 139 d. -

The Gilgameš Epic at Ugarit

The Gilgameš epic at Ugarit Andrew R. George − London [Fourteen years ago came the announcement that several twelfth-century pieces of the Babylonian poem of Gilgameš had been excavated at Ugarit, now Ras Shamra on the Mediterranean coast. This article is written in response to their editio princeps as texts nos. 42–5 in M. Daniel Arnaud’s brand-new collection of Babylonian library tablets from Ugarit (Arnaud 2007). It takes a second look at the Ugarit fragments, and considers especially their relationship to the other Gilgameš material.] The history of the Babylonian Gilgameš epic falls into two halves that roughly correspond to the second and first millennia BC respectively. 1 In the first millennium we find multiple witnesses to its text that come exclusively from Babylonia and Assyria. They allow the reconstruction of a poem in which the sequence of lines, passages and episodes is more or less fixed and the text more or less stable, and present essentially the same, standardized version of the poem. With the exception of a few Assyrian tablets that are relics of an older version (or versions), all first-millennium tablets can be fitted into this Standard Babylonian poem, known in antiquity as ša naqba īmuru “He who saw the Deep”. The second millennium presents a very different picture. For one thing, pieces come from Syria, Palestine and Anatolia as well as Babylonia and Assyria. These fragments show that many different versions of the poem were extant at one time or another during the Old and Middle Babylonian periods. In addition, Hittite and Hurrian paraphrases existed alongside the Akkadian texts. -

The Biblical Hebrew Wayyiqtol and the Evidence of the Amarna Letters from Canaan

Journal of Hebrew Scriptures Volume 16, Article 3 DOI:10.5508/jhs.2016.v16.3 The Biblical Hebrew wayyiqtol and the Evidence of the Amarna Letters from Canaan KRZYSZTOF J. BARANOWSKI Articles in JHS are being indexed in the ATLA Religion Database, RAMBI, and BiBIL. Their abstracts appear in Religious and Theological Abstracts. The journal is archived by Library and Archives Canada and is accessible for consultation and research at the Electronic Collection site maintained by Library and Archives Canada. ISSN 1203–1542 http://www.jhsonline.org and http://purl.org/jhs THE BIBLICAL HEBREW WAYYIQTOL AND THE EVIDENCE OF THE AMARNA LETTERS FROM CANAAN KRZYSZTOF J. BARANOWSKI UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW 1. THE PREFIXED PRETERITE IN SEMITIC PHILOLOGY If there is anything absolutely certain in the historical under- standing of the Semitic verbal system, it is the reconstruction of a short prefixed form with the perfective meaning, used typ- ically as the past tense in the indicative and as the directive- volitive form. Such an understanding is based on the existence and uses of the parallel forms of the short prefix conjugation in two major branches of the Semitic family: in East Semitic—the Preterite iprus and the Precative liprus; in West Semitic—various reflexes of the yaqtul conjugation, chiefly the Biblical Hebrew wayyiqtol.1 In the development of the West Semitic verbal sys- tem, the original perfective prefixed form was replaced by the suffixed form which eventually acquired the perfective meaning too.2 What is uncertain is when exactly this development took place. In relation to wayyiqtol and the use of the Preterite yiqtol without the conjunction wə in the Hebrew Bible, two questions remain without a satisfactory answer: what the evidence for the 1 Andersen 2000: 13–14, 17–20; Hasselbach and Huehnergard 2008: 416; Kouwenberg 2010: 587; Andrason 2011: 35–43; Cook 2012: 256–65, Hackett 2012: 111. -

Ancient-Knowledge-Networks.Pdf

Ancient Knowledge Networks Ancient Knowledge Networks A Social Geography of Cuneiform Scholarship in First-Millennium Assyria and Babylonia Eleanor Robson First published in 2019 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.uclpress.co.uk Text © Eleanor Robson, 2019 Images © Eleanor Robson and copyright holders named in captions, 2019 The author has asserted her rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Non- derivative 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Robson, E. 2019. Ancient Knowledge Networks: A Social Geography of Cuneiform Scholarship in First-Millennium Assyria and Babylonia. London: UCL Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787355941 Further details about Creative Commons licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Any third-party material in this book is published under the book’s Creative Commons license unless indicated otherwise in the credit line to the material. If you would like to re-use any third-party material not covered by the book’s Creative Commons license, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. ISBN: 978-1-78735-596-5 (Hbk.) ISBN: 978-1-78735-595-8 (Pbk.) ISBN: 978-1-78735-594-1 (PDF) ISBN: 978-1-78735-597-2 (epub) ISBN: 978-1-78735-598-9 (mobi) DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787355941 In memory of Bo Treadwell (1991–2014) Contents List of illustrations ix List of tables xv Acknowledgements xvi Bibliographical abbreviations xix Museum and excavation sigla xxi Dating conventions xxii Editorial conventions xxiii 1. -

Exile and Return Beihefte Zur Zeitschrift Für Die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft

Exile and Return Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft Edited by John Barton, Ronald Hendel, Reinhard G. Kratz and Markus Witte Volume 478 Exile and Return The Babylonian Context Edited by Jonathan Stökl and Caroline Waerzeggers DE GRUYTER ISBN 978-3-11-041700-5 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041928-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041952-8 ISSN 0934-2575 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Introduction | 1 Laurie E. Pearce Identifying Judeans and Judean Identity in the Babylonian Evidence | 7 Kathleen Abraham Negotiating Marriage in Multicultural Babylonia: An Example from the Judean Community in Āl-Yāhūdu | 33 Gauthier Tolini From Syria to Babylon and Back: The Neirab Archive | 58 Ran Zadok West Semitic Groups in the Nippur Region between c. 750 and 330 B.C.E. | 94 Johannes Hackl and Michael Jursa Egyptians in Babylonia in the Neo-Babylonian and Achaemenid Periods | 157 Caroline Waerzeggers Babylonian Kingship in the Persian Period: Performance and Reception | 181 Jonathan Stökl “A Youth Without Blemish, Handsome, Proficient in all Wisdom, Knowledgeable and Intelligent”: Ezekiel’s Access to Babylonian Culture | 223 H. G. M. Williamson The Setting of Deutero-Isaiah: Some Linguistic Considerations | 253 Madhavi Nevader Picking Up the Pieces of the Little Prince:Refractions of Neo-Babylonian Kingship Ideology in Ezekiel 40–48? | 268 VI Table of Contents Lester L. -

Beyond Empire: Complex Interaction Fields in the Late Bronze Age Levant by Samuel R Burns

Beyond Empire: Complex Interaction Fields in the Late Bronze Age Levant by Samuel R Burns A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors Department of Near Eastern Studies in The University of Michigan 2010 Advisors: Professor Gary M. Beckman Professor Henry T. Wright (Department of Anthropology) © Samuel R Burns 2010 To Nami ii Table of Contents Table of Figures ...................................................................................................................................iv Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................................v Abbreviations ......................................................................................................................................vii 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................1 2. Modeling Empires ........................................................................................3 2.1. What is an Empire? ..............................................................................................3 2.2. The Inadequacy of Empire ................................................................................13 2.3. Towards a New Model ........................................................................................17 3. Egypt and Amurru: Historical Background ............................................22 3.1. The Sources .........................................................................................................22 -

Elementary Sumerian Glossary” Author: Daniel A

Cuneiform Digital Library Preprints <http://cdli.ucla.edu/?q=cuneiform-digital-library-preprints> Hosted by the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (<http://cdli.ucla.edu>) Editor: Bertrand Lafont (CNRS, Nanterre) Number 3 Title: “Elementary Sumerian Glossary” Author: Daniel A. Foxvog Posted to web: 4 January 2016 Elementary Sumerian Glossary (after M. Civil 1967) Daniel A Foxvog Lecturer in Assyriology (retired) University of California at Berkeley A glossary suitable for the first several years of instruction, with emphasis on the vocabulary of easy literary texts, early royal inscriptions, and uncomplicated economic and administrative documents. Minor annual revisions add some new entries or update readings or translations. For additional terms and alternate readings and translations see the Electronic Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary on the Revised January 2016 Web. Not for Citation Guerneville, California USA 2 A a-è-a sudden onrush of water, damburst, flood wave kuš kuš a, `à water, fluid; semen, seed; offspring, child; father; A.EDIN.LÁ → ummu3 watercourse (cf. e) a-EN-da → a-ru12-da a Ah! (an interjection) (Attinger, Eléments p. 414) a-eštubku6 'carp flood,' early(?) flood (a literary phrase) a, a-a (now being read áya and aya respectively) father (Civil, AuOr 15, 52: “that time in early spring when, after the water temperature has reached at least 16° C, the large carps spawn, with spectacular splashings, in a-a-ugu(4) father who has begotten, one's own true father, progenitor the shallowest edges of ponds, marshes, and rivers,” cf. Lammerhirt, Šulgi F p. 77) a-ab-ba, a-aba (water of the) sea (cf. -

Cuneiform Texts in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

CUNEIFORM TEXTS IN THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART EDITED AND TRANSLATED I ALFRED B. MOLDENKE, PH. D. I PUBLISHED FOR THE MUSEUM NEW YORK 1893 PREFACE TO PARTS I. & II. In undertaking the publication of the cuneiform texts in the Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, I was prompted by the desire to render this small but interesting treasure accessible to students of the Semitic languages. These two parts are the first of a series of seven parts to be published as quickly as time permits. The texts referred to, are divided into two collections, known as the "Egibi," and the " Ward" collections. The former was purchased in 1878 from the British Museum, and the latter from the Rev. Dr. W. H. Ward of the Wolfe Expedition, by Gen. C. P. di Cesnola, the Director of the Museum. Part I contains 2I texts of the Egibi, and Part II, 35 of the Ward collection. Part I was published by me in June of this year under the title Babylonian Contract Tablets tn the Metrop5olitan iMuseum of Art. The causes that led me to republish it here were numerous and weighty. Chief among them I may mention that the volume was published as a doctor's dissertation, and in the hurry to get the book into print, many typographical errors were overlooked, and mistakes that should have been corrected, were left untouched. I trust that in' the present volume all such errors will have been avoided. Another cause was the desire of the Museum authorities to have some publi- cation of their collections to offer to inquiring strangers and to the learned public.