D3.1 Collection of 4 Case Study Reports on “Specific Social Exclusion Issues and Policy/Community Responses Encountered at ´Test Cases´”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Th E B E S T Q U E E R F Ilm S in the World

14th annual The w in or s l m d il f r e e u q T s e b e h T 28-30 APRIL 2017 Thank you To our generous sponsors bqff sponsors film sponsors This project is funded through the City of BQFF proudly auspiced by Greater Bendigo Community Grants Program Women’s Health Loddon Mallee PMS 1807 RED PMS 432 GREY PMS 142 GOLD Star Cinema SAILORS GULLY RD NAPIER ST VICTORIA ST EAGLEHAWK RD 7km Eaglehawk sundAY 30 Th april VENUESBARNARD ST 14th annual bqff breakfast: queer Conversations 10.00am @ The Capital ROWAN ST The BQFF breakfast is always a very popular event on the BQFF calendar, this year it has evolved to Queer Conversations, where the Dudley House way in which queers are represented in the media will be the topic of conversation. The conversation will be led by Bill Calder and Dr Graham Willet. Ticket price includes a lovely buffet breakfast. La Trobe Bendigo Bank Theatre, Art About Bill Calder and Dr Graham Willet ST SHORT Institute Capital Theatre For nearly two decades Bill Calder edited and published Australian gay newspapers and magazines, including Melbourne’s Brother Sister VIEW ST in the 1990s, and more recently Bnews. Previously he was the senior MACKENZIE ST news journalist at The Melbourne Times. Last year his book Pink Ink: The Golden Era for Gay and Lesbian Magazines was published by Bendigo Cambridge Scholars Publishing, based on his recently completed PhD Visitor Centre FRIDAY 28 Th april researching the history of gay and lesbian publications in Australia. -

Stedenbouwkundig Plan Omgeving Amstelstation

HOOGBOUW EFFECT RAPPORTAGE STEDENBOUWKUNDIG PLAN OMGEVING AMSTELSTATION CONCEPT HOOGBOUW EFFECT RAPPORTAGE INHOUD STEDENBOUWKUNDIG PLAN OMGEVING AMSTELSTATION 05 INLEIDING 07 HUIDIGE RUIMTELIJKE STRUCTUUR 07 Plangebied 09 BELEID EN RANDVOORWAARDEN 11 STEDENBOUWKUNDIG PLAN 11 Stedenbouwkundig inpassing 13 Programma 15 Inrichting openbare ruimte 15 Functie begane grondlaag 15 Sociale veiligheid 15 Uitzicht & privacy 19 LANDSCHAPPELIJKE INPASSING 19 Effecten 31 Werelderfgoed 33 HOOGTEBEPERKINGEN 33 Communicatieverkeer (straalpaden) 33 Radarzone Soesterberg 33 Vliegverkeer (Schiphol) 35 BEZONNING 37 WINDHINDER 39 SAMENVATTING & CONCLUSIE INLEIDING De Stadsdeelraad van Oost-Watergraafsmeer en de Gemeenteraad van Amsterdam hebben het stedenbouwkundig plan Omgeving Amstelstation in 2009 vastgesteld. De omgeving van het Amstelstation is een stationsmilieu, knooppunt én stadsentree. Een mix van wonen én werken én voorzieningen, die optimaal bereikbaar zijn. Volgens de nieuwe Ontwerp Structuurvisie van de gemeente Amsterdam moet ieder plan met hoogbouw vanaf ca 30 meter hoogte afzonderlijk worden beoordeeld. Het plan wordt in een Hoogbouw Effect Rapportage (HER) beoordeeld. Het plan bestaat uit vier gebouwen. Deze studie beschrijft de gevolgen van de twee torens (Blok A 85m en Blok D 100m) op het stadslandschap vanuit belangrijke gezichtpunten voor Amsterdammers en eventuele zichtbaarheid vanuit het ‘werelderfgoed’. De gezichtspunten zijn in overleg met DRO bepaald. Er wordt aandacht besteed aan de landschappelijke inpassing van de hoogbouw in de stedenbouwkundige structuur. Verder wordt ingegaan op de effecten van de beoogde hoogbouw in het Stationsgebied met betrekking tot wind en bezonning. Ook wordt aandacht besteed aan de functie op de begane grondlaag, inrichting van de omringende openbare ruimte, sociale veiligheid, uitzicht & privacy. Daarnaast is onderzocht of de hoogbouw leidt tot mogelijke hinder aan PTT-straalpaden en radarzones, of strijdigheid met het Luchthavenindelingsbesluit (hoogtebeperking van Schiphol). -

Transvaalbuurt (Amsterdam) - Wikipedia

Transvaalbuurt (Amsterdam) - Wikipedia http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transvaalbuurt_(Amsterdam) 52° 21' 14" N 4° 55' 11"Archief E Philip Staal (http://toolserver.org/~geohack Transvaalbuurt (Amsterdam)/geohack.php?language=nl& params=52_21_14.19_N_4_55_11.49_E_scale:6250_type:landmark_region:NL& pagename=Transvaalbuurt_(Amsterdam)) Uit Wikipedia, de vrije encyclopedie De Transvaalbuurt is een buurt van het stadsdeel Oost van de Transvaalbuurt gemeente Amsterdam, onderdeel van de stad Amsterdam in de Nederlandse provincie Noord-Holland. De buurt ligt tussen de Wijk van Amsterdam Transvaalkade in het zuiden, de Wibautstraat in het westen, de spoorlijn tussen Amstelstation en Muiderpoortstation in het noorden en de Linnaeusstraat in het oosten. De buurt heeft een oppervlakte van 38 hectare, telt 4500 woningen en heeft bijna 10.000 inwoners.[1] Inhoud Kerngegevens 1 Oorsprong Gemeente Amsterdam 2 Naam Stadsdeel Oost 3 Statistiek Oppervlakte 38 ha 4 Bronnen Inwoners 10.000 5 Noten Oorsprong De Transvaalbuurt is in de jaren '10 en '20 van de 20e eeuw gebouwd als stadsuitbreidingswijk. Architect Berlage ontwierp het stratenplan: kromme en rechte straten afgewisseld met pleinen en plantsoenen. Veel van de arbeiderswoningen werden gebouwd in de stijl van de Amsterdamse School. Dit maakt dat dat deel van de buurt een eigen waarde heeft, met bijzondere hoekjes en mooie afwerkingen. Nadeel van deze bouw is dat een groot deel van de woningen relatief klein is. Aan de basis van de Transvaalbuurt stonden enkele woningbouwverenigingen, die er huizenblokken -

Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies

Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies Volume 37 2020 Article 8 4-2020 Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sigma Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation (2020) "Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies," Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies: Vol. 37 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sigma/vol37/iss1/8 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. LEAD EDITOR EDITOR-IN-CHIEF MANAGING EDITORS Naomi Hilton Tanner Cox Rebecca Russavage Hayley Whitlock EDITORIAL BOARD XXXVII 2020 VOLUME STUDIES AND INTERNATIONAL POLITICAL OF SIGMA: JOURNAL Nathan McQuarrie Casey Cunningham Parker Gardner Abigail Ferrell Journal of Political and International Studies FACULTY ADVISOR VOLUME XXXVII Scott Cooper SPECIAL THANKS TO FACULTY Michael Barber Joel Selway Adam Brown Dan Nielson Eric Hyer BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies is a multidisciplinary publication of student articles on topics in political science and international studies. Sigma addresses topics such as economics, international relations, political science, and area studies. Our aim is to publish the work of diligent students who have fresh policy recommendations and new perspectives to offer, which would otherwise go unnoticed. Sigma is supported and sponsored by the BYU chapters of the Pi Sigma Alpha (National Political Honor Society) and Sigma Iota Rho (Honor Society for International Studies). -

Uitvoeringsprogramma Aanpak Binnenstad Onderscheidt 6 Prioriteiten Die Samen En in Wisselwerking Met Elkaar Bijdragen Aan De Opgaven in De Binnenstad

AANPAK BINNENSTAD Uitvoeringsprogramma december 2020 i. Inhoud 1. Vooraf 3 Van ambitie naar maatregelen 4 2. Aanleiding 5 3. Ambitie 6 4. Uitvoeringsprogramma 7 5. Opgaven 9 BINNENSTAD AANPAK Enkele voorbeelden van Aanpak Binnenstad 10 2 6. Maatregelen 11 6.1 Functiemenging en diversiteit 12 6.2 Beheer en handhaving 16 6.3 Een waardevolle bezoekerseconomie 20 6.4 Versterken van de culturele verscheidenheid en buurtidentiteiten 23 6.5 Bevorderen van meer en divers woningaanbod 26 6.6 Meer verblijfsruimte en groen in de openbare ruimte 29 7. Organisatie en financiën 32 8. Samenwerking en voortgang 33 UITVOERINGSPROGRAMMA 1. Vooraf In mei 2020 is in een raadsbrief de Aanpak Binnenstad gelanceerd. Deze aanpak combineert maatregelen en visie voor zowel de korte als langere termijn, formuleert de opgaven in de binnenstad breed en in samenhang, maar stelt tegelijkertijd ook prioriteiten. Deze aanpak bouwt voort op dat wat is ingezet door de gemeente en tal van anderen rond de binnenstad, maar maakt waar nodig ook scherpe keuzes. En deze aanpak pakt problemen aan én biedt perspectief. Wat ons treft in de vele gesprekken die Een deel van deze maatregelen is reeds De kracht van een set maatregelen is dat wij in de afgelopen maanden gevoerd in gang gezet, want we beginnen niet bij ze goed te adresseren en concreet zijn. hebben met bewoners, ondernemers, nul. Andere maatregelen nemen wij in De kwetsbaarheid is dat ze een zekere vastgoedeigenaren en culturele onderzoek of voorbereiding en met weer mate van uitwisselbaarheid suggereren. instellingen, is dat er een breed gedragen andere starten wij in het kader van dit Dat laatste willen wij weerleggen. -

A B N N N Z Z Z C D E F G H I J K

A8 COENTUNNELWEG W WEG ZIJKANAAL G AMMERGOU G R O 0 T E Gemeente Zaanstad D N M E E R Gemeente Oostzaan K L E I N E AA V A N B BOZEN M E E R NOORDER BOS LANDSMEER E EKSTRAA SYMON SPIERSWEG V E E R MEERTJE T ZUIDEINDE AFRIKAHAVEN NOORDER-IJPLAS NOOR : BAARTHAVEN D ZEE ISAAC KAN Broekermeerpolder NOORDERWEG AAL ( IN AANLEG ) K N O O P P U N T ZUIDEINDE DORS MACHINEWEG RUIGOORD ZAANDAM C O E N P L E I N WIM ARKEN AE THOMASSENHAVEN HET SCHOUW Volgermeer- Gemeente Waterland SPORTPARK R M EER EN W E G BR OEKE Belmermeerpolder RINGWEG-NOO MIDD Hemspoortunnel OOSTZANER- polder Houtrak- WERF DIRK KADOELENWEG polder R D Gemeente Landsmeer RIJPERWEG METSELAARHAVEN A 1 0 SWEG AMERIKAHAVEN R OOSTZANERWERF H e m p o n t ENAA STELLINGWEG MOL S T R A A T SPORTPARK STEN T OR MELKWEG UITDAM O O TW B EG ANKERWEG W E G RUIJGOORDWEG WESTHAVENWEG STOOM KADOELEN BROEKERGOUW TER A M D M Burkmeer- ER STELLINGWEG UIT D IE ELBAWEG C A R L R E AVEN SLOCH Veenderij H Windturbine IJNI HORNWEG ERSH polder V o e t v e e r CACAO AVEN KADO SPORTPARK Grote Blauwe Polder KOMETENSINGEL Sportpark Zunderdorp E R R.I. Groote OT DIE LANDS ELENWEG TUINDORP KADOELEN LATEXWEG IJpolder METEORENWEG Tuindorp AAL SL NOORDERBREEDTE N WESTHAVEN OOSTZAAN KA COENTUNNEL CORNELIS DOUWESWEG Oostzaan MIDDENWEG MEERDER JAN VAN RIEBEECK G O U W HOLY KOFFIEWEG RUIGOORD MIDDENWEG RUIGOORD PETROLEUM HOLLANDSCH HOLYSLOOT DIJK NDAMMER HAVEN NOORD E : INCX POPP AUSTRALIEHA V E N ZIJKANAAL I POMONASTRAAT NWEG HORNWEG WESTERLENGTE RWEG OCEANE USSEL A N A N A S HAVEN NIEUWE HEMWEG P L E I N BUIKSLOOT RDE R.I. -

Reestraat Hartenstraat Gasthuis Molensteeg Oude Spiegelstraat

Basis Folder_9_straatjes leeg_Opmaak 1 28-02-16 17:14 Pagina 1 ® WINKELEN IN DE 9 STRAATJES,® SHOPPING IN THE 9 STREETS, AMSTERDAM IN OPTIMA FORMA AMSTERDAM IN TOP FORM 9 straatjes vol schilderachtige monumenten en een uniek aanbod 9 picturesque alleyways in the Amsterdam canal belt. Full of quirky gespecialiseerde, veelal authentieke winkels, galeries en de meest little shops, designer boutiques, vintage stores and hidden cafés bijzondere horeca. Middenin de grachtengordel, in het hart van and restaurants. Charming and delightfull. In the hart of Unesco’s Unesco’s Werelderfgoed, net achter het Paleis op de Dam tussen World Heritage, just behind the Royal Palace at Dam Square and on Raadhuisstraat en Leidsegracht. the way from Anne Frank to Rijksmuseum. ‘Heel de wereld is rond Amsterdam gebouwd,’ schreef de All the world is built around Amsterdam, wrote the famous Dutch beroemde dichter Vondel in de 17e eeuw. In die Gouden Eeuw poet Vondel in the 17th century. During that golden age the old barstte het oude stadsgebied uit haar voegen en ontwierp men city within the Singel bursted out of its seams. So the Canal Belt vanaf het Singel de grachtengordel. In korte tijd werd de stad was designed with a ring of Herengracht, Keizersgracht and kilometers gracht rijker en oogstte wereldfaam met de Heren-, Prinsengracht. Keizers- en Prinsengracht. The four canals were connected by little side-streets, with names De 4 hoofdgrachten werden door dwarsstraatjes met elkaar referring to the old skintanning industry. As Huiden, Ree, Beren en verbonden, met namen die herinneren aan de leerbewerking. Zoals Wolvenstraat stands for Skin, Dear, Bears, Woolfsstreet! Then, at Huiden, Ree, Beren, Wolven, Run en Hartenstraat. -

33Rd Annual Meeting Trauma and Complexity: from Self to Cells

33rd Annual Meeting Trauma and Complexity: From Self to Cells Final Program November 9-11, 2017 Pre-Meeting Institutes, November 8 Continuing Medical Education Jointly Provided by Amedco and Palmer House Hilton the International Society for Chicago, Illinois, USA Traumatic Stress Studies www.istss.org 33rd Annual Meeting The ISTSS 33rd Annual Meeting is supported in part by: Silver Supporter Wiley Journal of Traumatic Stress Peer-reviewed original papers focused on theoretical formulations, research, treatment, prevention education/training and legal and policy concerns. 2 Final Program www.istss.org 33rd Annual Meeting Welcome Welcome to the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies 33rd Annual Meeting, “Trauma and Complexity: From Self to Cells.” Traumatic life events exert effects that can be anything but simple. Such complexity is evident in the interaction between traumatic event characteristics (e.g., different kinds of trauma exposure; military vs. civilian, sexual vs. non-sexual) and person characteristics (e.g., sex, age, ethnicity, sexual orientation). Complexity is further revealed by the fact that trauma affects not only specific individuals, but the social relationships within which they are embedded, including intimate partners, peers, and family members through to larger communities, countries and cultures. Trauma also can be understood as a complex temporal process that unfolds over multiple timescales, including over the course of a single event, developmental period, lifetime course, and period in history. Finally, as implied by the meeting subtitle, the experience and outcomes of traumatic stress take place across multiple levels, beginning with first-person self- experiences that are encoded and further recursively expressed through myriad neurobiological markers. -

Le Isole Minori Elisabetta Vulcano 2009

CITTA’ DI VENEZIA Assessorato Ambiente - Osservatorio Naturalistico della Laguna Centro Studi Riviera del Brenta In collaborazione con: Coop. Hyla – CAI – Uff. Educazione Ambientale – Istituzione Parco Laguna Corso didattico formativo LA LAGUNA DI VENEZIA: genesi, evoluzione, naturalità e salvaguardia - Anno 2008/2009 - LE ISOLE MINORI: UN PATRIMONIO DELLA STORIA ALLA DERIVA DEL PRESENTE Elisabetta Vulcano (Architetto) La struttura topografica della città nelle sue linee generali è già formata nella prima metà del XIII secolo. La pianta di Venezia disegnata da Paolino da Venezia (1270-1344), e inserita nel suo “Compendium” detto anche “Chronologia magna” (1346), restituisce la forma della città secondo un aspetto cronologico: come doveva presentarsi Venezia nel IX secolo (ma con alcuni particolari riferiti addirittura all'VIII secolo) e come doveva essere nel XII secolo, con aggiunte relative alla sua configurazione coeva all'autore. Dopo la morte di Fra' Paolino la pianta pergamenacea rimase nascosta a tutti per quattrocento anni. Solo nel 1730 Tomaso Temanza scoprì la pergamena e nel 1781 realizzò una incisone su rame nella quale riportò con una calligrafia più chiara il disegno e le scritte, incisione che diede alle stampe. La Pianta di Venezia di Paolino da Venezia (Biblioteca Marciana, Venezia) Il Chronicon marciano 1. Porto del Lido 2. San Pietro 3. Arsenale 4. Isola di San Giorgio 5. Piazza San Marco 6. Rialto 7. Murano 8. Cannaregio 9. Giudecca 10 . San Nicolò L’incisione di Benedetto Bordone del 1528 è la più antica pianta prospettica della laguna. In questa, sono pochi i toponimi della città, molti delle isole e dei lembi di terraferma. È la prima mappa che, oltre alla città, comprende anche la laguna. -

Project of Territorial Governance of Tourism in Venice

Project of territorial governance of tourism in Venice Project of territorial governance of tourism in Venice 2 Project of territorial governance of tourism in Venice Table of Contents FOREWORD.............................................................................................................................................................7 FIRST PART:...........................................................................................................................................................11 THE START OF A PARTICIPATORY ROUTE.................................................................................................................11 1. The functions of tourism and the regulatory framework...............................................................................13 2. Tourism in Venice..........................................................................................................................................15 3. The resident population................................................................................................................................22 4. The stages of the participatory route.............................................................................................................25 5. Principal mission statements of the projects presented and adopted by the Technical Working Group..........27 SECOND PART:.......................................................................................................................................................43 OPERATIONAL -

Financing Land Grab

[Released under the Official Information Act - July 2018] 1 Financing Land Grab The Direct Involvement of Israeli Banks in the Israeli Settlement Enterprise February 2017 [Released under the Official Information Act - July 2018] 2 [Released under the Official Information Act - July 2018] 3 Financing Land Grab The Direct Involvement of Israeli Banks in the Israeli Settlement Enterprise February 2017 [Released under the Official Information Act - July 2018] 4 Who Profits from the Occupation is a research center dedicated to exposing the commercial involvement of Israeli and international companies in the continued Israeli control over Palestinian and Syrian land. Who Profits operates an online database, which includes information concerning companies that are commercially complicit in the occupation. In addition, the center publishes in-depth reports and flash reports about industries, projects and specific companies. Who Profits also serves as an information center for queries regarding corporate involvement in the occupation. In this capacity, Who Profits assists individuals and civil society organizations working to end the Israeli occupation and to promote international law, corporate social responsibility, social justice and labor rights. www.whoprofits.org | [email protected] [Released under the Official Information Act - July 2018] 5 Contents Executive Summary 7 Introduction 10 Israeli Construction on Occupied Land 14 Benefits for Homebuyers and Contractors in Settlements 16 Financing Construction on Occupied Land 20 The Settlement -

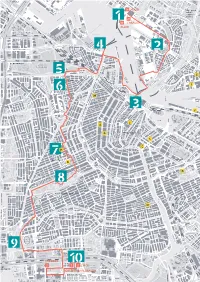

DE BODEM ONDER AMSTERDAM Een Geologische Stadswandeling

EEN GEOLOGISCHE STADSWANDELING Wim de Gans OVER DE AUTEUR Dr. Wim de Gans (Amersfoort, 1941) studeerde aardwetenschappen aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Na zijn afstuderen was hij als docent achtereenvolgens verbonden aan de Rijks Universiteit Groningen en de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Na deze universitaire loopbaan was hij jaren lang werkzaam als districtsgeoloog bij de Rijks Geologische Dienst (RGD), die in 1997 is overgegaan naar TNO. De schrijver is bij TNO voor de Geologische Dienst Nederland vooral bezig met het populariseren van de geologie van Nederland. Hij schreef talrijke publicaties en enkele boeken waaronder het Geologieboek Nederland (ANWB/TNO). DE BODEM ONDER AMSTERDAM EEN GEOLOGISCHE STADSWANDELING Wim de Gans VOORWOORD Wanneer je door de binnenstad van Amsterdam wandelt, is het moeilijk voor te stellen dat onder de gebouwen, straten en grachten niet alleen veen maar ook veel andere grondsoorten voorkomen die een belangrijk stempel hebben gedrukt op de ontwikkeling van de stad. Hier ligt een aardkundige geschiedenis die enkele honderdduizenden jaren omvat. Landijs, rivieren, zee en wind hebben allemaal bijgedragen aan de vorming van een boeiende en afwisselende bodem, maar ook een bodem waarop het moeilijk wonen of bouwen is. Hoewel de geologische opbouw onder de stad natuurlijk niet direct zichtbaar is, zijn de afgeleide effecten hiervan vaak wel duidelijk. Maar men moet er op gewezen worden om ze te zien. Vandaar dit boekje. Al wandelend en lezend gaat er een aardkundige wereld voor u open waaruit blijkt dat de samenstelling van de ondergrond van Amsterdam grote invloed heeft gehad op zowel de vestiging en historische ontwikkeling van de stad als op het bouwen en wonen, door de eeuwen heen.