Peters, Edward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geology of the Connaigre Peninsula and Adjacent

10′ 55° 00′ LEGEND 32 MIDDLE PALEOZOIC LATE NEOPROTEROZOIC 42 42 DEVONIAN LONG HARBOUR GROUP (Units 16 to 24) 86 Mo BELLEORAM GRANITE Rencontre Formation (Units 19 to 24) 47° 50′ 32 47 Grey to pink, medium- and fine-grained equigranular granite containing many small, dark-grey and green (Units 19 and 20 occur only in the northern Fortune Bay 47a to black inclusions; 47a red felsite and fine-grained area; Unit 22 occurs only on Brunette Island) 47b granite, developed locally at pluton’s margin; 47b Red micaceous siltstone and interbedded, buff-weath- 10 pink-to brown quartz-feldspar porphyry (Red Head 24 31 Porphyry) ering, quartzitic arkose and pebble conglomerate 20′ Pink, buff-weathering, medium- to coarse-grained, Be88 OLD WOMAN STOCK 23 cross-bedded, quartzitic arkose and granule to pebble Pink, medium- and coarse-grained, porphyritic biotite 42 46 23a conglomerate; locally contains red siltstone; 23a red 32 granite; minor aplite 31 23b pebble conglomerate; 23b quartzitic arkose as in 23, MAP 98-02 GREAT BAY DE L’EAU FORMATION (Units 44 and 45) containing minor amounts of red siltstone 37 9 83 Pyr 45 Grey mafic sills and flows 22 Red and grey, thin-bedded siltstone, and fine-grained 37 GEOLOGY OF THE CONNAIGRE PENINSULA 19b sandstone and interbedded buff, coarse-grained, cross 10 25 19b Pyr 81 Red, purple and buff, pebble to boulder conglomerate; bedded quartzitic arkose; minor bright-red shale and 32 25 42 44 W,Sn 91 minor green conglomerate and red and blackshale; green-grey and black-grey and black siltstone AND ADJACENT AREAS, -

Source Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland And

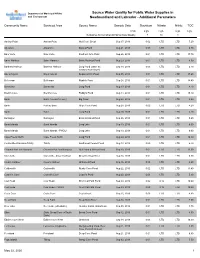

Department of Municipal Affairs Source Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in and Environment Newfoundland and Labrador - Additional Parameters Community Name Serviced Area Source Name Sample Date Strontium Nitrate Nitrite TOC Units mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality 7 10 1 Anchor Point Anchor Point Well Cove Brook Sep 17, 2019 0.02 LTD LTD 7.20 Aquaforte Aquaforte Davies Pond Aug 21, 2019 0.00 LTD LTD 6.30 Baie Verte Baie Verte Southern Arm Pond Sep 26, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 17.70 Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Pond Aug 29, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 9.50 Bartletts Harbour Bartletts Harbour Long Pond (same as Sep 18, 2019 0.03 LTD LTD 6.70 Castors River North) Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Sugarloaf Hill Pond Sep 05, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 17.60 Belleoram Belleoram Rabbits Pond Sep 24, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 14.40 Bonavista Bonavista Long Pond Aug 13, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.10 Brent's Cove Brent's Cove Paddy's Pond Aug 14, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 15.10 Burin Burin (+Lewin's Cove) Big Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.90 Burin Port au Bras Gripe Cove Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.02 LTD LTD 4.20 Burin Burin Long Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.10 Burlington Burlington Eastern Island Pond Sep 26, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 9.60 Burnt Islands Burnt Islands Long Lake Sep 10, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 6.00 Burnt Islands Burnt Islands - PWDU Long Lake Sep 10, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 6.00 Cape Freels North Cape Freels North Long Pond Aug 20, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 10.30 Centreville-Wareham-Trinity Trinity Southwest Feeder Pond Aug 13, 2019 0.00 LTD LTD 6.70 Channel-Port -

The Resettlement of Pushthrough 4 Pushthrough Is Approved For

The Resettlement of Pushthrough 4 Pushthrough is approved for Resettlement Introduction Mr. Shirley, an official from the Government of fishing was the major economic influence. The Newfoundland and Labrador, came to population had declined dramatically from 204 Pushthrough in September 1967 to discuss in 1966 to 165 in 1968. Of those 70 were over resettlement with the Reverend Reuben the age of 21. The community had 35 privately- Hatcher, the Anglican Parish priest. It was not owned homes, mostly two storey and several the resettlement of Pushthrough that he newer bungalows. There was a two-room wanted to discuss but certain communities in school, enrolment 33 pupils from Grade 1 to Reverend Hatcher’s parish that extended west Grade 11. There were 3 general stores. Under from Pushthrough to Francois. Reverend community organization he noted the Society of Hatcher was away. Mr. Shirley reportedly talked United Fishermen and the Anglican Church, with a few men who told him said there was adding the names of William Rowsell and Mrs. little interest in resettlement in Pushthrough. In George Courtney after each. He identified two fact, two families had recently moved there individuals in the power structure of under the Resettlement Programme. Mr. Shirley also reported that some people he saw felt “that Pushthrough would phase out slowly within the next few years.” They suggested that many would move to Bay d’Espoir if employment opportunities existed there. Snapshot of Pushthrough C.A. Evans, Mr. Shirley’s colleague, visited a year later. He reported that much had changed (Credit: St. Peter’s School http://tinyurl.com/cygr96s) in Pushthrough: “A great many have already Pushthrough: William Simms, storekeeper, and moved.” He left a petition form “which they Samuel Kendell, junior light keeper. -

Really No Merchant : an Ethnohistorical Account of Newman and Company and the Supplying System in the Newfoundland Fishery at Ha

~ationalLibrary BiMiotwnationale i+u ot Canada du Canada Canadian Theses Service Setvice des theses canadie Ottawa. Canada KIA ON4 ', I NOTICE he of this microform is heavily dependent upon the La qualit6 de cette microforme depend grandement de la quality of the original thesis submitted for n?icrofilming. qualit6 de la these soumise au microfilmage.Nous avons €very eff& has been made to ensure the highest quality of tout fait pour assurer une qualife sup6rieure de repfoduc- reproduction~possible. tion. I! pages are missing, contact the university which granted S'il manque des pages, veuillez communiquer avec the degree. I'universitb qui a confer4 le grade. Some pages may have indistinct print especially if the La qualit6 d'impression de certaines pages put laisser a original pages were typed with a poor typewriter ribbon or desirer, surtout si les pages originales ont Bte dactylogra- if the university sent us an inferior photocopy. phiees a I'aide d'un ruban us6 ou si runiversitb nous a fa~t parvenir une photocopie de qualit6 inferieure. Reproduction in full or in part of this microform is vemed La reproduction, meme partielle, de cette microforme est by the Canadian Copyright Act. R.S.C. 1970. C. g30, and soumise ti la Loi canadienne sur le droit d'auteur, SRC subsequent amendments. 1970. c. C-30. et ses amendements subsequents. NL-339 (r. 8&01)c - . - - t REALLY NO MERCHANT: AN ETHNOHISTORICAL ACCBUNT OF HEWMAN AND COMPANY AND THE SUPPLYING SYSTEM IN TBE NEWFOUNDLAND - FISHERY AT HARBOUR BRETON, 1850-1900 David Anthony Macdonald B.A. -

Appendix a Waste Management Regions

Appendix A Waste Management Regions – Newfoundland And Labrador Review of the Provincial Solid Waste Management Strategy 27 28 Review of the Provincial Solid Waste Management Strategy Regions on the Island (Eight): Northern Peninsula Region The Northern Peninsula Waste Management Region spans from River of Ponds in the west to Englee in the east and extends to Quirpon in the north. Western Region The Western Newfoundland Waste Management Region spans from Bellburns in the north to Ramea in the south and extends east to White Bay. Baie Verte-Green Bay Region The Baie Verte-Green Bay Waste Management Region includes all communities on the Baie Verte Peninsula and in Green Bay South, spanning from Westport in the west to Brighton in the east. This region also includes Little Bay Islands. Coast of Bays Region The Coast of Bays Waste Management Region includes the Connaigre Peninsula, spanning from the Head of Bay D’Espoir in the north to Harbour Breton in the south. This region also includes the communities of McCallum, Gaultois and Rencontre East. Burin Peninsula Region The Burin Peninsula Waste Management Region spans from Grand le Pierre and Monkstown in the north to Point May and Lamaline in the south. Central Region The Central Newfoundland Waste Management Region spans from Buchans in the west to Terra Nova National Park in the east and extends north to Twillingate. This region also includes Change Islands and Fogo Island. Discovery Region The Discovery Waste Management Region includes the entire Bonavista Peninsula, spanning from Port Blandford in the west to the Town of Bonavista in the east. -

Lithogeochemistry of Gaultois Granite, Northwest Brook Complex and North Bay Granite Suite Intrusive Rocks, St

Current Research (2020) Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Natural Resources Geological Survey, Report 201, pages 4970 LITHOGEOCHEMISTRY OF GAULTOIS GRANITE, NORTHWEST BROOK COMPLEX AND NORTH BAY GRANITE SUITE INTRUSIVE ROCKS, ST. ALBAN’S MAP AREA A. Westhues Regional Geology Section ABSTRACT Intrusive rocks occur in two different tectonic zones in the St. Alban’s map area (NTS 01M/13) and, a) intrude the Little Passage Gneiss of the Gander Zone in the east, and b) the volcanosedimentary rocks of the Baie d’Espoir Group, Exploits Subzone of the Dunnage Zone in the west. The oldest intrusive rock suite in the area is the Late Silurian leuco to mesocratic, medium to coarsegrained, megacrystic, lineated and foliated biotite ± tourmaline ± titanite Gaultois Granite (~421 Ma) in the Gander Zone. The rocks are dominantly granodiorite and it is therefore suggested, herein, to use the informal name Gaultois Granite suite. Subunits of the Gaultois Granite suite include hornblende tonalite, quartz diorite, and a slightly younger non foliated posttectonic coarse equigranular biotite–titanite monzonite (419.6 ± 0.46 Ma). Also, the undated Northwest Brook Complex twomica granite and numerous felsic aplite and pegmatite dykes intrude the Gaultois Granite suite. Intrusive rocks in the Dunnage Zone are part of the laterally extensive Devonian North Bay Granite Suite with several major units (one of the youngest dated at ca. 396 Ma). The East Bay Granite in the southwest is typically an equigranular biotite ± muscovite granite to granodiorite that can be weakly to moderately foliated. The second major unit of the North Bay Granite Suite is a weakly to moderatelyfoliated, megacrystic biotite granodiorite to granite named the Upper Salmon Road Granite. -

CLPNNL By-Laws

COLLEGE BY-LAWS Table of Contents PART I: TITLE AND DEFINITIONS . 2 PART II: COLLEGE ADMINISTRATION . 3 PART III: COLLEGE BOARD AND STAFF. 5 PART IV: ELECTION(S). 8 PART V: MEETINGS . 11 PART VI: BOARD COMMITTEES . 14 PART VII: FEES/LICENSING. 15 PART VIII: GENERAL. 16 Appendix A: Electoral Zones. 17 Appendix B: Nomination Form . 29 1 PART I: TITLE AND DEFINITIONS By-laws Relating to the Activities of the College of Licensed Practical Nurses of Newfoundland and Labrador References in this document to the Act , Regulations and By-laws refer to the Licensed Practical Nurses Act (2005) ; the Licensed Practical Nurses Regulations (2011) and the By-laws incorporated herein, made under the Licensed Practical Nurses Act, 2005 . 1. Title These By-laws may be cited as the C ollege of Licensed Practical Nurses of Newfoundland and Labrador By-laws . 2. Defi nitions In these Bylaws , “act” means the Licensed Practical Nurses Act, 2005 ; “appointed Board member” means a member of the Board appointed under section 4 of the Act ; “Board” means the Board of the College of Licensed Practical Nurses of Newfoundland and Labrador as referred to in section 3 of the Act ; “Chairperson” means the chairperson of the Board elected under Section 3(8) of the Act ; “College” means the College of Licensed Practical Nurses of Newfoundland and Labrador as established by section 3 of the Act ; “elected Board member” means a member of the Board elected under section 3 of the Act ; “committee member” means a member of a committee appointed by the Board; “Registrar” means the Registrar of the College of Licensed Practical Nurses of Newfoundland and Labrador; “Licensee” means a member of the College who is licensed under section 12 of the Act ; “Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN)” means a practical nurse licensed under the Act ; and “Regulation” means a Regulation passed pursuant to the Act , as amended. -

The Newfoundland and Labrador Gazette

THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE PART I PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Vol. 90 ST. JOHN’S, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 23, 2015 No. 43 QUIETING OF TITLES ACT and Labrador, Trial Division, Grand Bank, particulars of such adverse claim and serve the same together with an 2015 06G 0121 Affidavit verifying same on the undersigned Solicitors for SUPREME COURT OF the Petitioner on or before the 20th day of November, 2015, NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR after which date no party having any claim shall be TRIAL DIVISION (GENERAL) permitted to file the same or to be heard except by special leave of the Court and subject to such conditions as the NOTICE OF APPLICATION under the Quieting of Titles Court may deem just. Act, RSNL1990 cQ-3, as amended. All such adverse claims shall be investigated then in such NOTICE IS HEREBY given to all parties that LEONARD manner as the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and BARRY and NANCY BARRY, of the Town of Port Rexton, Labrador, Trial Division, Grand Bank, may direct in the District of Trinity North, in the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador, has applied to the Supreme DATED AT Clarenville, in the Province of Newfoundland Court, Trial Division, Grand Bank, to have title to all that and Labrador, this 21st day of September, 2015. piece or parcel of property situate at Port Rexton, in the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador which property is MILLS PITTMAN & TWYNE more particularly described in Schedule "A" hereto annexed Solicitors for the Applicants and shown in Schedule "B" hereto annexed. PER: Gregory J. French ALL BEARINGS aforementioned, for which LEONARD ADDRESS FOR SERVICE: BARRY and NANCY BARRY claim to be the owners 111 Manitoba Drive. -

The Resettlement of Pushthrough, Newfoundland, in 1969

The Resettlement of Pushthrough, Newfoundland, in 1969 RaymOND B. BlakE INTRODUCTION One of the largest internal state-sponsored migrations of people within Can- ada occurred in Newfoundland and Labrador between 1954 and 1975.1 Some 300 rural communities were vacated and 30,000 people relocated to larger communities, greatly reshaping settlement distributions and patterns in out- port regions, particularly along the south coast, in Placentia, Bonavista, and Notre Dame bays, and on the southeast coast of Labrador. Many who moved under the program welcomed their relocation from small, isolated outports as improving immensely their social and economic prospects even if their com- munities were dismembered in the process. There was little public opposition until the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the program had largely run its course. Resettlement then became a cause célèbre of what journalist and writer Sandra Gwyn called the Newfoundland cultural renaissance, led primarily by a St. John’s artistic and intellectual class that considered resettlement a mis- guided policy imposed by callous state elites, insensitive social and economic planners, and ill-informed politicians that recklessly interfered in the lives of ordinary, hard-working people.2 It indicted Joseph R. Smallwood, the prov- ince’s Premier from 1949 to 1972, for his failure to appreciate the uniqueness of outport life in his relentless search for modernity and North American con- sumer culture.3 His attempt to change the spatial patterns of settlement through the depopulation of isolated settlements did not simply threatened the physical, social, and cultural landscapes of the past, they argued, but was newfoundland and labrador studies, 30, 2 (2015) 1719-1726 The Resettlement of Pushthrough 221 paramount to destroying a people by obliterating its culture, history, and trad- itions. -

Introduction the Story of How Europeans First Settled Newfoundland Southeast of Ireland

TOPIC 3.2 What countries of origin are represented in your community or region? What is your family’s ancestry? Introduction The story of how Europeans first settled Newfoundland southeast of Ireland. Because of this, the effects of the and Labrador is somewhat different from European migratory fishery are still prevalent today. immigration to other parts of North America. Our province’s European population came almost entirely Another distinctive characteristic of settlement in from England and Ireland, with small but significant Newfoundland and Labrador is that it was encouraged inputs from the Channel Islands, Scotland, and France. by merchants rather than being the product of individual initiative. Unlike other areas of North America, where The two most important regions providing the labour in ships brought large numbers of families seeking a better the migratory fishery also became the primary sources life, immigrants to the island of Newfoundland were of the settled population. To this day, the great majority primarily young, single men brought by merchants on of Newfoundlanders and Labradorians can trace their their ships to work for them. There were few women or ancestry to late eighteenth and early nineteenth century children in the early years. immigrants from the southwest of England and the * 3.7 Early settlement *Today, Mi’kmaq is the Some historians suggest that by 1800 there were hundreds of communities in Newfoundland with perhaps 15 000 permanent residents. However, definitions of common usage. “permanent resident” vary and other historians’ calculations suggest that there were closer to 10 000 permanent residents. 184 3.8 An immigrant arrives in St. -

RESEARCH NOTE They Cannot Pay Us in Money: Newman and Company and the Supplying System in the Newfoundland Fishery, 1850-1884

RESEARCH NOTE They Cannot Pay Us in Money: Newman and Company and the Supplying System in the Newfoundland Fishery, 1850-1884 DURING THE 19TH CENTURY THE Newfoundland fishery was conducted for the most part by inshore fishermen who owned and operated small boats and produced salt-cod for export. The merchants who exported the finished product seldom caught or processed the fish themselves but supplied the fishermen who did. Fish went to market only once or twice a year and the problem of maintaining the fishery's labour force over the year was a serious one. As the structure of the fishery developed in the 19th century, merchants extended a range of supplies to fishermen and fishermen came to depend on these supplies for the maintenance of their families and for the conduct of the fishery. Although the role of the exporting merchants in production was indirect but important, these merchants have been seen as doing only what merchants do — buying short, selling long and pocketing the difference. The supplying system has been explained as a means of helping them to do so by enslaving workers and appropriating surplus value through the extension of credit and by dealing, without cash, in truck.1 The classic description (though itself derivative) of the Newfoundland supplying system has been that of Lord Amulree, who wrote that "It was obvious that the fishermen could not conduct the fishery from their own resources and the custom grew up under which each fisherman went to a merchant and obtained from him, on credit, supplies of equipment and food to enable him and his family to live".2 At the end of the season the fisherman returned to the merchant with his catch of fish which was priced by the merchant, as were the supplies he had received. -

Membership Register MBR0009

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF MAY 2020 CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR MEMBERSHI P CHANGES TOTAL DIST IDENT NBR CLUB NAME COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 2733 013821 BISHOPS FALLS CANADA N 3 4 05-2020 29 2 0 0 -4 -2 27 2733 013823 BOTWOOD CANADA N 3 4 05-2020 51 3 0 0 -2 1 52 2733 013824 BUCHANS CANADA N 3 4 02-2019 24 0 0 0 0 0 24 2733 013825 BURGEO CANADA N 3 4 05-2020 26 1 0 0 -1 0 26 2733 013828 CHANNEL PORT AUX BASQUES CANADA N 3 4 03-2020 47 4 2 0 -6 0 47 2733 013831 CORNER BROOK CANADA N 3 4 05-2020 14 6 0 1 -4 3 17 2733 013832 DEER LAKE CANADA N 3 4 05-2020 21 0 0 0 0 0 21 2733 013835 ENGLISH HARBOUR WEST CANADA N 3 4 02-2019 43 0 0 0 0 0 43 2733 013836 FLOWERS COVE CANADA N 3 4 05-2020 26 1 0 0 -3 -2 24 2733 013843 HARBOUR BRETON CANADA N 3 4 05-2020 41 1 0 0 -2 -1 40 2733 013846 LEWISPORTE CANADA N 3 4 02-2020 17 0 0 0 -2 -2 15 2733 013849 MILLTOWN BAIE D'ESPOIR CANADA N 3 4 03-2020 33 23 0 0 -3 20 53 2733 013851 NEW WORLD ISLAND CANADA N 3 4 09-2019 15 0 0 0 0 0 15 2733 013853 NORRIS POINT CANADA N 3 4 03-2020 28 0 0 0 -2 -2 26 2733 013855 PASADENA CANADA N 3 4 05-2020 42 0 0 0 -5 -5 37 2733 013858 ST ANTHONY CANADA N 3 4 06-2019 17 0 0 0 0 0 17 2733 013863 STEPHENVILLE CROSSING CANADA N 3 4 04-2020 7 1 0 0 0 1 8 2733 013864 SPRINGDALE CANADA N 3 4 05-2020 37 1 0 0 0 1 38 2733 013865 STEPHENVILLE CANADA N 3 4 05-2020 49 0 0 0 -1 -1 48 2733 013868 TWILLINGATE CANADA N 3 4 02-2020 35 0 0 0 -3 -3 32 2733 013869 UNITED TOWNS