The Resettlement of Pushthrough, Newfoundland, in 1969

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geology of the Connaigre Peninsula and Adjacent

10′ 55° 00′ LEGEND 32 MIDDLE PALEOZOIC LATE NEOPROTEROZOIC 42 42 DEVONIAN LONG HARBOUR GROUP (Units 16 to 24) 86 Mo BELLEORAM GRANITE Rencontre Formation (Units 19 to 24) 47° 50′ 32 47 Grey to pink, medium- and fine-grained equigranular granite containing many small, dark-grey and green (Units 19 and 20 occur only in the northern Fortune Bay 47a to black inclusions; 47a red felsite and fine-grained area; Unit 22 occurs only on Brunette Island) 47b granite, developed locally at pluton’s margin; 47b Red micaceous siltstone and interbedded, buff-weath- 10 pink-to brown quartz-feldspar porphyry (Red Head 24 31 Porphyry) ering, quartzitic arkose and pebble conglomerate 20′ Pink, buff-weathering, medium- to coarse-grained, Be88 OLD WOMAN STOCK 23 cross-bedded, quartzitic arkose and granule to pebble Pink, medium- and coarse-grained, porphyritic biotite 42 46 23a conglomerate; locally contains red siltstone; 23a red 32 granite; minor aplite 31 23b pebble conglomerate; 23b quartzitic arkose as in 23, MAP 98-02 GREAT BAY DE L’EAU FORMATION (Units 44 and 45) containing minor amounts of red siltstone 37 9 83 Pyr 45 Grey mafic sills and flows 22 Red and grey, thin-bedded siltstone, and fine-grained 37 GEOLOGY OF THE CONNAIGRE PENINSULA 19b sandstone and interbedded buff, coarse-grained, cross 10 25 19b Pyr 81 Red, purple and buff, pebble to boulder conglomerate; bedded quartzitic arkose; minor bright-red shale and 32 25 42 44 W,Sn 91 minor green conglomerate and red and blackshale; green-grey and black-grey and black siltstone AND ADJACENT AREAS, -

Exerpt from Joey Smallwood

This painting entitled We Filled ‘Em To The Gunnells by Sheila Hollander shows what life possibly may have been like in XXX circa XXX. Fig. 3.4 499 TOPIC 6.1 Did Newfoundland make the right choice when it joined Canada in 1949? If Newfoundland had remained on its own as a country, what might be different today? 6.1 Smallwood campaigning for Confederation 6.2 Steps in the Confederation process, 1946-1949 THE CONFEDERATION PROCESS Sept. 11, 1946: The April 24, 1947: June 19, 1947: Jan. 28, 1948: March 11, 1948: Overriding National Convention The London The Ottawa The National Convention the National Convention’s opens. delegation departs. delegation departs. decides not to put decision, Britain announces confederation as an option that confederation will be on on the referendum ballot. the ballot after all. 1946 1947 1948 1949 June 3, 1948: July 22, 1948: Dec. 11, 1948: Terms March 31, 1949: April 1, 1949: Joseph R. First referendum Second referendum of Union are signed Newfoundland Smallwood and his cabinet is held. is held. between Canada officially becomes are sworn in as an interim and Newfoundland. the tenth province government until the first of Canada. provincial election can be held. 500 The Referendum Campaigns: The Confederates Despite the decision by the National Convention on The Confederate Association was well-funded, well- January 28, 1948 not to include Confederation on the organized, and had an effective island-wide network. referendum ballot, the British government announced It focused on the material advantages of confederation, on March 11 that it would be placed on the ballot as especially in terms of improved social services – family an option after all. -

Charitable Impact (“CHIMP”) Foundation: Analysis of 11650 Gifts

Charitable Impact (“CHIMP”) Foundation: Analysis of 11,650 Gifts (2011-2018) Vivian Krause April 28, 2020 NOTICE AND DISCLAIMER This document offers a summary of the analysis, questions and opinions of the author, Vivian Krause. While the information herein is believed to be accurate and reliable, it is not guaranteed to be so as the information available to me is limited to publicly available data. The author makes this document available without warranty of any kind. Users of this material should exercise due diligence to ensure the accuracy and currency of all information. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice, and may become out-dated as additional information is identified, disclosed, or otherwise becomes available. This document may or may not be updated. Vivian Krause reserves the right to amend this document on the basis of information received after it was initially written. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored, distributed or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of Vivian Krause. Gifts Made By Charitable Impact Foundation (2011) # of % of Total Value of % of Total Amount of Gift By # of Gifts By $ of Gifts Gifts Gifts Gifts Value of Gifts <$10 68 12.1% $450 0.1% $10-$24 115 20.5% $2,484 0.6% $25-$49 95 16.9% $4,026 0.9% 491 87% $43,442 10% $50-$99 93 16.5% $8,195 1.9% $100-$249 78 13.9% $12,849 3.0% $250-$499 42 7.5% $15,438 3.6% $500-$999 35 6.2% $23,549 5.4% $1K-$2,499 18 3.2% $30,384 7.0% $2,500-$5K 8 1.4% $27,731 6.4% 65 12% $120,547 28% $5K-$10K 3 0.5% $24,060 5.5% $10K-$25K 1 0.2% $14,823 3.4% $25K-$50K 5 0.9% $158,858 36.6% $50K-$100K 0 0.0% $0 0.0% 6 1% $270,459 62% $100K- $1M 1 0.2% $111,601 25.7% $1M-$2M $2M-$20M 0 0% $0 0% >$20M Total: 562 100% $434,448 100% 562 100% $434,448 100% Summary: In 2011, almost 90 percent of CHIMP’s gifts were for less than $500 meanwhile one of CHIMP’s 562 gifts accounted for more than 60 percent of the total value of all gifts. -

2021 Tide Tables Vol. 1

2021 Tide Tables Vol. 1 Metadata File identifier f5f708e7-650e-48d5-9ad7-222f8de0db7c ISO Language code English Character Set UTF8 Date stamp 07-01-2021 11:13:12 Metadata standard name ISO 19115:2003/19139 Metadata standard version 1.0 Contact General Telephone Individual name Voice Stephane Lessard 418-649-6351 Organisation name Canadian Coast Guard Position name Address Operational Systems Engineer Role code Electronic mail address Point of contact [email protected] Other language French Reference System Information Identifier Unique resource identifier WGS 1984 Data identification Abstract 2021 Tide Tables for the Atlantic Coast and the Bay of Fundy, produced by the Canadian Hydrographic Service Progress Completed Spatial Representation Type Vector ISO Language code English Character Set UTF8 Supplemental Information The CHS Tide Tables provide predicted times and heights of the high and low waters associated with the vertical movement of the tide. https://www.tides.gc.ca/ eng/data/predictions/2021#vol1 Citation Title 2021 Tide Tables Vol. 1 Publication 2021-01-07 Revision 2021-01-07 Citation identifier http://www.marinfo.gc.ca/e-nav/gn/description/eng/6fa5c795-c62c-4d3d-bd05-d05fab260f6a Point of contact Address Electronic mail address [email protected] General General Organisation name OnLine resource Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS) Role code Linkage Publisher http://www.shc.gc.ca/ Protocol WWW:LINK-1.0-http--link Description Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS) Maintenance information Maintenance Frequency Continual -

Labrador; These Will Be Done During the Summer

Fisheries Peches I and Oceans et Oceans 0 NEWFOUNDLAND REGION ((ANNUAL REPORT 1985-86 Canada ) ceare SMALL CRAFT HARBOURS BRANCH Y.'• ;'''' . ./ DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES AND OCEANS NEWFOUNDLAND REGION . 0 4.s.'73 ' ANNUAL REPORT - 1985/86 R edlioft TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. Overview and Summary 1 2. Small Craft Harbours Branch National Planning Framework 3 3. Long Range Planning: Nfld. Region 8 4. Project Evaluation 10 5. Harbour Maintenance and Development Programs 11 6. Harbour Operations 16 7. Budget Utilization (Summary) 1985/86 17 APPENDICES 1. Photos 2. Harbour Classification 3. Minimum Services Offered 4. Condition Rating Scale 5. Examples of Project Type 6. Project Evaluation 7. Regular Program Projects 1985/86 8. Joint SCH-Job Creation Projects 1984/85/86 9. Joint SCH-Job Creation Projects 1985/86/87 10. Dredging Projects Utilizing DPW Plant 11. Advance Planning 12. Property Acquisition Underway 1 OVERVIEW AND SUMMARY Since the establishment of Small Craft Harbours Branch of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans in 1973, the Branch has been providing facilities such as breakwaters, wharves, slipways, gear storage, shore protection, floats and the dredging of channels and basins, in fishing and recreational harbours within the Newfoundland Region. This third annual report produced by Small Craft Harbours Branch, Newfoundland Region, covers the major activities of the Branch for the fiscal year 1985/86. During the fiscal year continuing efforts were made towards planning of the Small Craft Harbours Program to better define and priorize projects, and to maximize the socio-economic benefits to the commercial fishing industry. This has been an on-going process and additional emphasis was placed on this activity over the past three years. -

Lighthouses – Clippings

GREAT LAKES MARINE COLLECTION MILWAUKEE PUBLIC LIBRARY/WISCONSIN MARINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY MARINE SUBJECT FILES LIGHTHOUSE CLIPPINGS Current as of November 7, 2018 LIGHTHOUSE NAME – STATE - LAKE – FILE LOCATION Algoma Pierhead Light – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan - Algoma Alpena Light – Michigan – Lake Huron - Alpena Apostle Islands Lights – Wisconsin – Lake Superior - Apostle Islands Ashland Harbor Breakwater Light – Wisconsin – Lake Superior - Ashland Ashtabula Harbor Light – Ohio – Lake Erie - Ashtabula Badgeley Island – Ontario – Georgian Bay, Lake Huron – Badgeley Island Bailey’s Harbor Light – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan – Bailey’s Harbor, Door County Bailey’s Harbor Range Lights – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan – Bailey’s Harbor, Door County Bala Light – Ontario – Lake Muskoka – Muskoka Lakes Bar Point Shoal Light – Michigan – Lake Erie – Detroit River Baraga (Escanaba) (Sand Point) Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – Sand Point Barber’s Point Light (Old) – New York – Lake Champlain – Barber’s Point Barcelona Light – New York – Lake Erie – Barcelona Lighthouse Battle Island Lightstation – Ontario – Lake Superior – Battle Island Light Beaver Head Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – Beaver Island Beaver Island Harbor Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – St. James (Beaver Island Harbor) Belle Isle Lighthouse – Michigan – Lake St. Clair – Belle Isle Bellevue Park Old Range Light – Michigan/Ontario – St. Mary’s River – Bellevue Park Bete Grise Light – Michigan – Lake Superior – Mendota (Bete Grise) Bete Grise Bay Light – Michigan – Lake Superior -

Letter to John Bromley RE Chimp Tech Inc. (28April2020)

Correspondence #7 Letter to Blake Bromley April 28, 2020 RE: Quest University, CHIMP and other Bromley Charities 1. Excerpts of the Financial Statements of CHIMP Foundation Showing Payments to Chimp Technology Inc. for $23 Million (2014-2018) (10 pages) 2. CHIMP Foundation: Analysis of 11,650 Gifts (2011-2018) (234 pages) Total: 253 pages April 28, 2020 To: John Bromley, President & CEO of Charitable Impact Foundation (“CHIMP”) c.c. Blake Bromley Christopher Richardson Leslie Brandlmayr Victoria Nalugwa Nadine Britton c.c. Neil Bunker, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP Dr. George Iwama, President, Quest University Mr. Jordan Sturdy, MLA, West Vancouver-Sea to Sky RE: Quest University, CHIMP and other Bromley Charities Further to my letter of April 21, I am writing again to inquire about the role of CHIMP and other Bromley Charities in the early funding and start-up of Quest University. Last week, I asked to speak with you about gifts to CHIMP for a total of $120 million: Ø $ 34.4 million from Almoner Foundation (2011-2019) Ø $ 33.8 million from Foundation For Public Good (2017-2019) Ø $ 12.1 million from the Association for the Advancement of Scholarship (2012-2018) Ø $ 10.5 million from Eden Glen Foundation (2017) Ø $ 10.1 million from Timothy Foundation (2012-2017) Ø $ 7.0 million from Mighty Oaks Foundation (2014) Ø $ 4.0 million from Headwaters Foundation (2011) Ø $ 3.7 million from Homestead on the Hill Foundation (2018) Ø $ 3.4 million from Global Charity Fund (2014) Ø $ 1.0 million from Theanon Foundation (2011-2014) $ 120 million TOTAL On the basis of my research, it is clear to me that these gifts for $120 million stem from tax-receipted donations reported by charities involved with funds for starting Quest University. -

LOVELL's GAZETTEER of the DOMINION of CANADA. Wide, and Throughout Its Entire Length It Is OXFORD, Or HOLY, LAKE, in Keewatin Completely Sheltered on Both Sides

, 726 LOVELL'S GAZETTEER OF THE DOMINION OF CANADA. wide, and throughout its entire length it is OXFORD, or HOLY, LAKE, in Keewatin completely sheltered on both sides. It has dist., N.W.T., north-east of Lake Winnipeg, good anchorage ground and considerable depth Man. of water, and is navigable for vessels of the OXFORD MILLS, a post village in Grenville largest capacity on the lake. A large number CO., Ont., and a station on the C.P.R. It con- of vessels are engaged in the grain and lumber tains 3 churches, 3 stores, 1 hotel, 1 carriage factory, trade. Pop., about 10,000. 1 wagon factory, 1 cheese factory and 1 carding mill. Pop., OWIKANO LAKE, a body of water in Brit. 350. Columbia. Area, 62,720 acres. OXFORD STATION, a post village in Gren- OWL'S HEAD, a beautiful mountain on Lake ville CO., Ont., on the Ottawa & Prescott div. M^mphremagog, about 6 miles from Georgeville, of the C.P.R., 6 miles from Kemptville. It con- Stanstead co.. Que. There is a large hotel at tains 2 churches (Episcopal and Methodist), 1 its base, and a landing place for steamers ply- butter and cheese factory, i store and tele- ing between Magog and Newport. graph and express offices. Pop.. lOO. OWL'S HEAD HARBOR, a post village in OXLEY, a post village in Essex co., Ont., Halifax co., N.S., 48 miles east of Dartmouth, on Lake Erie, 4 1-2 miles from Harrow, and of late on the I.C.R. It contains 1 church of Eng- noted as a summer resort for the re- sidents land, 1 Union hall, 1 store and 1 lobster can- of Detroit. -

Source Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland And

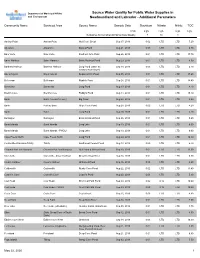

Department of Municipal Affairs Source Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in and Environment Newfoundland and Labrador - Additional Parameters Community Name Serviced Area Source Name Sample Date Strontium Nitrate Nitrite TOC Units mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality 7 10 1 Anchor Point Anchor Point Well Cove Brook Sep 17, 2019 0.02 LTD LTD 7.20 Aquaforte Aquaforte Davies Pond Aug 21, 2019 0.00 LTD LTD 6.30 Baie Verte Baie Verte Southern Arm Pond Sep 26, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 17.70 Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Pond Aug 29, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 9.50 Bartletts Harbour Bartletts Harbour Long Pond (same as Sep 18, 2019 0.03 LTD LTD 6.70 Castors River North) Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Sugarloaf Hill Pond Sep 05, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 17.60 Belleoram Belleoram Rabbits Pond Sep 24, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 14.40 Bonavista Bonavista Long Pond Aug 13, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.10 Brent's Cove Brent's Cove Paddy's Pond Aug 14, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 15.10 Burin Burin (+Lewin's Cove) Big Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.90 Burin Port au Bras Gripe Cove Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.02 LTD LTD 4.20 Burin Burin Long Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.10 Burlington Burlington Eastern Island Pond Sep 26, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 9.60 Burnt Islands Burnt Islands Long Lake Sep 10, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 6.00 Burnt Islands Burnt Islands - PWDU Long Lake Sep 10, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 6.00 Cape Freels North Cape Freels North Long Pond Aug 20, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 10.30 Centreville-Wareham-Trinity Trinity Southwest Feeder Pond Aug 13, 2019 0.00 LTD LTD 6.70 Channel-Port -

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | 0 | P | Q-R | S | T | U-V | W | X-Y-Z A Abraham's Cove Adams Cove, Conception Bay Adeytown, Trinity Bay Admiral's Beach Admiral's Cove see Port Kirwan Aguathuna Alexander Bay Allan’s Island Amherst Cove Anchor Point Anderson’s Cove Angel's Cove Antelope Tickle, Labrador Appleton Aquaforte Argentia Arnold's Cove Aspen, Random Island Aspen Cove, Notre Dame Bay Aspey Brook, Random Island Atlantic Provinces Avalon Peninsula Avalon Wilderness Reserve see Wilderness Areas - Avalon Wilderness Reserve Avondale B (top) Baccalieu see V.F. Wilderness Areas - Baccalieu Island Bacon Cove Badger Badger's Quay Baie Verte Baie Verte Peninsula Baine Harbour Bar Haven Barachois Brook Bareneed Barr'd Harbour, Northern Peninsula Barr'd Islands Barrow Harbour Bartlett's Harbour Barton, Trinity Bay Battle Harbour Bauline Bauline East (Southern Shore) Bay Bulls Bay d'Espoir Bay de Verde Bay de Verde Peninsula Bay du Nord see V.F. Wilderness Areas Bay L'Argent Bay of Exploits Bay of Islands Bay Roberts Bay St. George Bayside see Twillingate Baytona The Beaches Beachside Beau Bois Beaumont, Long Island Beaumont Hamel, France Beaver Cove, Gander Bay Beckford, St. Mary's Bay Beer Cove, Great Northern Peninsula Bell Island (to end of 1989) (1990-1995) (1996-1999) (2000-2009) (2010- ) Bellburn's Belle Isle Belleoram Bellevue Benoit's Cove Benoit’s Siding Benton Bett’s Cove, Notre Dame Bay Bide Arm Big Barasway (Cape Shore) Big Barasway (near Burgeo) see -

Small Craft Harbours Directorate Sixth Annual .P

Government o C nada Gouvernement du Canada + Fisheries and Oc ans Peches et Oceans DFO Library / MPO Bib iotheque 1111 14046773 SMALL CRAFT HARBOURS DIRECTORATE SIXTH ANNUAL L .P,ROPE TY MANAGEMENT MEETING *Ns. DIRECTION GtENMALE DES PORTS POUR PETITS BATEAUX SIXIEME REUNI g N ANNUELLE SUR LA GESTIC} IMMOBILIERE L _ N JL 86 .R42 A56 1980 AGENDA 6TH ANNUAL MEETING OF SMALL CRAFT HARBOURS PROPERTY MANAGEMENT Date: May 13 to 15, 1980, inclusive. Time: 0900 hours. Place: Maritime Region - Barrington Inn, Halifax, Nova Scotia. Review Leases and Licences Assignments Sub-Leases Changes in Area f/.4 Changes in Name Cancellations Plans Plotting on Plans I Numbering System I.R.S. Monthly Report Construction on property not owned by Federal Crown. Procedure Acquisition of Property Disposal of Property Schedule of Rates Review of Harbour Management - West Coast - Mr. G.S. Wallace Harbour Manager - Appointments Harbour Manager - Commissions - Leases and Licences Deletion of Debts Use of Harbours by Tour Boats Berthage Vessels not tied up at Government Wharf Accidents Reporting Liability Law Talk by Justice Official Film Nova Scotia Wharves Tour tlednesday, May 14 8:00 A.M. Halifax to Lunenburg 9:30 A.M. Tour harbour facilities at Lunenburg Battery Point 10:00 A.M. Tour National Sea Fish Plant - Battery Point 11:00 A.M. Tour Lunenburg Harbour and Museum . 12:00 Lunch in Lunenburg 1:30 Return to Halifax 3:00-3:30 Arrive in Halifax JL 86 .R42 A56 1980 Canada. Small Craft Harb... Small Craft Harbours Directorate, sixth annua... 259588 14046773 c.1 Vol. 3, No. -

Laying Down Special Conditions Governing Imports of Fishery Products Originating in Canada

15 . 9 . 93 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 232/43 COMMISSION DECISION of 26 July 1993 laying down special conditions governing imports of fishery products originating in Canada (93/495/EEC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, the rules set out in Chapter V of the Annex to Directive 91 /493/EEC and regarding fulfilment of requirements Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European equivalent to those laid down by that Directive for the Economic Community, approval of establishments ; Having regard to Council Directive 91 /493/EEC of Whereas the measures provided for in this Decision are in 22 July 1991 laying down the health conditions for the accordance with the opinion of the Standing Veterinary production and the placing on the market of fishery Committee, products ('), and in particular Article 1 1 thereof, Whereas a group of Commission experts has conducted an inspection visit to Canada to verify the conditions HAS ADOPTED THIS DECISION : under which fishery products are produced, stored and dispatched to the Communiy ; Whereas the provisions of Canadian legislation on health Article 1 inspection and monitoring of fishery products may be considered equivalent to those laid down in Directive The Inspection Directorate of the Department of Fishe 91 /493/EEC ; ries and Oceans shall be the competent authority in Canada for verifying and certifying compliance of fishery Whereas the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (Minis products with the requirements of Directive 91 /493/EEC. tere des Peches et Oceans), the competent Canadian authority, and its Inspection Directorate (Direction des Services d'Inspection) are capable of effectively verifying the application of the laws in force ; Article 2 Whereas the procedure for obtaining the health certificate Fishery products originating in Canada must meet the referred to in point (a) of Article 11 (4) of Directive following conditions : 91 /493/EEC must also cover the definition of a model certificate, the minimum requirements regarding the 1 .