Avraham and Sarah in Provence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TALMUDIC STUDIES Ephraim Kanarfogel

chapter 22 TALMUDIC STUDIES ephraim kanarfogel TRANSITIONS FROM THE EAST, AND THE NASCENT CENTERS IN NORTH AFRICA, SPAIN, AND ITALY The history and development of the study of the Oral Law following the completion of the Babylonian Talmud remain shrouded in mystery. Although significant Geonim from Babylonia and Palestine during the eighth and ninth centuries have been identified, the extent to which their writings reached Europe, and the channels through which they passed, remain somewhat unclear. A fragile consensus suggests that, at least initi- ally, rabbinic teachings and rulings from Eretz Israel traveled most directly to centers in Italy and later to Germany (Ashkenaz), while those of Babylonia emerged predominantly in the western Sephardic milieu of Spain and North Africa.1 To be sure, leading Sephardic talmudists prior to, and even during, the eleventh century were not yet to be found primarily within Europe. Hai ben Sherira Gaon (d. 1038), who penned an array of talmudic commen- taries in addition to his protean output of responsa and halakhic mono- graphs, was the last of the Geonim who flourished in Baghdad.2 The family 1 See Avraham Grossman, “Zik˙atah shel Yahadut Ashkenaz ‘el Erets Yisra’el,” Shalem 3 (1981), 57–92; Grossman, “When Did the Hegemony of Eretz Yisra’el Cease in Italy?” in E. Fleischer, M. A. Friedman, and Joel Kraemer, eds., Mas’at Mosheh: Studies in Jewish and Moslem Culture Presented to Moshe Gil [Hebrew] (Jerusalem, 1998), 143–57; Israel Ta- Shma’s review essays in K˙ ryat Sefer 56 (1981), 344–52, and Zion 61 (1996), 231–7; Ta-Shma, Kneset Mehkarim, vol. -

ACC14 and Tctacci2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures B.Pdf

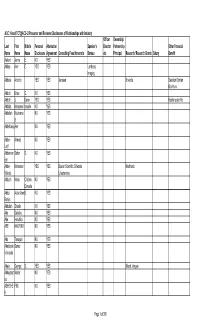

ACC.14 and TCT@ACC-i2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures of Relationships with Industry Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Aaland Jenna E. NO YES Abbas Amr E. YES YES Lantheus Imaging Abbate Antonio YES YES Janssen Novartis Swedish Orphan Biovitrum Abbott Brian G. NO YES Abbott J. Dawn YES YES Boston scientific Abdalla Mohamed Ismaile NO YES Abdallah Mouhama NO YES d Abdelbaky Amr NO YES Abdel- Ahmed NO YES Latif Abdelmon Sahar S. NO YES eim Abdel- Mohamed YES YES Boston Scientific, Edwards Medtronic Wahab Lifesciences Abduch Maria Cristina NO YES Donadio Abdul Aizai Azan B. NO YES Rahim Abdullah Shuaib NO YES Abe Daisuke NO YES Abe Haruhiko NO YES ABE NAOYUKI NO YES Abe Takayuki NO YES Abedzade Sanaz NO YES h Anaraki Abela George S. YES YES Merck, Amgen Abhayarat Walter NO YES na ABHISHE FNU NO YES K Page 1 of 350 Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Abidi Syed NO YES Abidov Aiden NO YES Abi-samra Freddy Michel NO YES Abizaid Alexandre YES YES Abbott, Boston Scientific Abo- Elsayed NO YES Salem Abou- Alex NO YES Chebl AbouEzze Omar F NO YES ddine Aboulhosn Jamil A. YES YES GE Medical, Actelion United Therapeutics, Actelion Pharmaceuticals Pharmaceuticals Abraham Jacob NO YES Abraham JoEllyn Moore NO YES Abraham Maria Roselle NO YES Abraham Theodore P. -

400 Editor RABBI SHIMON HELINGER

ב"ה למען ישמעו • פרשת תצוה • 400 EDITOR RABBI SHIMON HELINGER PURIM A POTENT DAY INTENSE REJOICING The Rebbe once said: It’s obvious that we must distance ourselves entirely The Zohar notes that Purim is similar to Yom We read in the Gemara that on Purim one must drink from anything negative (“cursed be Haman”), HaKipurim. This means that what is accomplished “until he cannot differentiate (“ad d’lo yada”) between and seek to treasure and embrace all good things on Yom Kippur by fasting can be accomplished ‘cursed be Haman’ and ‘blessed be Mordechai.’ ” (“blessed be Mordechai”). That applies at any time. on Purim by rejoicing. Furthermore, the very The Gemara relates a story of two amoraim, Rabbah The unique aspect of Purim is that we can accomplish name Kipurim (“like Purim”), implies that Purim and Rav Zeira, who had their Purim seuda together, this by allowing our neshama to express itself freely. is the greater Yom-Tov, impacting a person sharing profound secrets of the Torah over a This kind of avoda is superior to serving HaShem by more powerfully. number of cups of wine. However, Rav Zeira was so means of conscious thought (yada). Indeed, in this Indeed, Chazal teach that when Moshiach comes, all overwhelmed by the intense kedusha of Rabbah’s kind of avoda we can resemble the Yidden at the the Yomim-Tovim will cease to exist; only the Yom- revelations that his neshama left his body. time of the Purim story who, when the inner power Tov of Purim will remain. Chassidus explains that of their neshamos surfaced, fulfilled all the mitzvos the joy and holiness of Purim are so great, that even faithfully, even to the point of mesiras nefesh. -

Sanhedrin 053.Pub

ט"ז אלול תשעז“ Thursday, Sep 7 2017 ן נ“ג סנהדרי OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT to apply stoning to other cases גזירה שוה Strangulation for adultery (cont.) The source of the (1 ואלא מכה אביו ואמו קא קשיא ליה, למיתי ולמיגמר מאוב וידעוני R’ Yoshiya’s opinion in the Beraisa is unsuccessfully וכו ‘ ליגמרו מאשת איש, דאי אתה רשאי למושכה להחמיר עליה וכו‘ .challenged at the bottom of 53b lists אלו הן הנסקלין Stoning T he Mishnah of (2 The Mishnah later derives other cases of stoning from a many cases which are punished with stoning. R’ Zeira notes gezeirah shavah from Ov and Yidoni. R’ Zeira questions that the Torah only specifies stoning explicitly in a handful גזירה שוה of cases, while the other cases are learned using a דמיהם בם or the words מות יומתו whether it is the words Rashi states that the cases where we find . אוב וידעוני that are used to make that gezeirah shavah. from -stoning explicitly are idolatry, adultery of a betrothed maid . דמיהם בם Abaye answers that it is from the words Abaye’s explanation is defended. en, violating the Shabbos, sorcery and cursing the name of R’ Acha of Difti questions what would have bothered R’ God. Aruch LaNer points out that there are three addition- Zeira had the gezeirah shavah been made from the words al cases where we find stoning mentioned outright (i.e., sub- ,mitting one’s children to Molech, inciting others to idolatry . מות יומתו In any case, there .( בן סורר ומורה—After R’ Acha of Difti suggests and rejects a number of and an recalcitrant son גזירה possible explanations Ravina explains what was troubling R’ are several cases of stoning which are derived from the R’ Zeira asks Abaye to identify the source from which . -

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon Ha-Ra and Motzi Shem Ra and Disclosing Another’S Confidential Secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon ha-ra and motzi shem ra and disclosing another’s confidential secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech Deut. 24:9 - "Remember what the L-rd your G-d did unto Miriam by the way as you came forth out of Egypt." Specifically, she spoke against her brother Moses. Yerushalmi Berachos 1:2 Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai said, “Had I been at Mount Sinai at the moment when the torah was given to Yisrael I would have demanded that man should have been created with two mouths- one for Torah and prayer and other for mundane matters. But then I retracted and exclaimed that if we fail and speak lashon hara with only one mouth, how much more so would we fail with two mouths Bavli Arakhin15b R. Yochanan said in the name of R.Yosi ben Zimra: He who speaks slander, is as though he denied the existence of the Lord: With out tongue will we prevail our lips are our own; who is lord over us? (Ps.12:5) Gen R. 65:1 and Lev.R. 13:5 The company of those who speak slander cannot greet the Presence Sotah 5a R. Hisda said in the name of Mar Ukba: When a man speaks slander, the holy one says, “I and he cannot live together in the world.” So scripture: “He who slanders his neighbor in secret…. Him I cannot endure” (Ps. 101:5).Read not OTO “him’ but ITTO “with him [I cannot live] Deut.Rabbah 5:10 R.Mana said: He who speaks slander causes the Presence to depart from the earth below to heaven above: you may see foryourselfthat this is so.Consider what David said: “My soul is among lions; I do lie down among them that are aflame; even the sons of men, whose teeth are spears and arrows, and their tongue a sharp sword” (Ps.57:5).What follows directly ? Be Thou exalted O God above the heavens (Ps.57:6) .For David said: Master of the Universe what can the presence do on the earth below? Remove the Presence from the firmament. -

Miriyam Goldman OA Thesis 9Dec20.Pdf (247.7Kb)

The Living Stone: The Talmudic Paradox of the Seventh Month Gestational Viability vs. the Eighth Month Non-Viability Presented to the S. Daniel Abraham Honors Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Completion of the Program Stern College for Women Yeshiva University December 9, 2020 Miriyam A. Goldman Mentor: Rabbi Dr. Richard Weiss, Biology Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………….…. 4 Background to Pregnancy ……………………………………………………………………… 5 Talmudic Sources on the Dilemma ……………………………………………………………. 6 Meforshim on the Dilemma ……………………………………………………………………. 9 Secular Sources of the Dilemma ………………………………………………………………. 11 The Significance of Hair and Nails in Terms of Viability……………………………….……... 14 The Definition of Nefel’s Impact on Viability ……………………………………………….. 17 History of Premature Survival ………………………………………………………………… 18 Statistics on Prematurity ………………………………………………………………………. 19 Developmental Differences Between Seventh and Eighth Months ……………………….…. 20 Contemporary Talmudic Balance of the Dilemma..…………………………………….…….. 22 Contemporary Secular Balance of the Dilemma .……………………………………….…….. 24 Evaluation of Talmudic Accreditation …………………………………………………..…...... 25 Interviews with Rabbi Eitan Mayer, Rabbi Daniel Stein, and Rabbi Dr. Richard Weiss .…...... 27 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………….…. 29 References…..………………………………………………………………………………..… 34 2 Abstract This paper reviews the viability of premature infants, specifically the halachic status of those born in -

Doing Talmud: an Ethnographic Study in a Religious High School in Israel

Doing Talmud: An Ethnographic Study in a Religious High School in Israel Thesis submitted for the degree of “Doctor of Philosophy” by Aliza Segal Submitted to the Senate of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem May 2011 Iyyar 5771 This work was carried out under the supervision of: Prof. Marc Hirshman Dr. Zvi Bekerman Acknowledgements If an apt metaphor for the completion of a dissertation is the birthing of a child, then indeed it takes a village to write a dissertation. I am fortunate that my village is populated with insightful, supportive and sometimes even heroic people, who have made the experience not only possible but also enriching and enjoyable. My debt of gratitude to these villagers looms large, and I would like to offer a few small words of thanks. To my advisors, Dr. Zvi Bekerman and Professor Menachem (Marc) Hirshman, for their generosity with time, insight, expertise, and caring. I have been working with Zvi since my MA thesis, and he has shaped my world view not only as a researcher but also as an individual. His astute and lightening-speed comments on everything I have ever sent him to read have pushed me forwards at every stage of my work, and it is with great joy that I note that I have never left his office without something new to read. Menachem has brought his keen eye and sharp wit to the project, and from the beginning has been able to see the end. His attention to the relationship between structure and content has informed my work as both a writer and a reader. -

Shavuot 5780 Divrei Torah

Shavuot 5780 Divrei Torah Sponsored by: Debbie and Orin Golubtchik in honor of: The yahrzeits of Orin's parents חביבה בת שמואל משה בן חיים ליב Barbara and Simcha Hochman & family in memory of: • Simcha’s father, Rabbi Jonas Hochman a"h and • Gedalya ben Avraham, Blima bat Yaakov, Eeta bat Noach and Chaya bat Gedalya, who were murdered upon arrival at Birkenau on the 2nd day Shavuot. Table of Contents Page 3 Forward by Rabbi Adler ”That which you can and cannot do on Yom Tov אכל נפש“ Page 5 Yaakov Blau “Shifting voices in the narrative of Tanach” Page 9 Leeber Cohen “The Importance of Teaching Torah to Grandchildren” Page 11 Elchanan Dulitz “Bezchus Rabbi Dr. Baruch Tzvi ben R. Reuven Nassan z”l Mai Chanukah” Page 15 Martin Fineberg “Shavuos 5780 D’var Torah” Page 19 Yehuda Halpert “Ruth and Orpah’s Wedding Album: Fake News or Biblical Commentary” Page 23 Terry Novetsky “The “Mitzva” of Shavuot” Page 31 Yitzchak Shulman “Parshat Behaalotcha “ Page 33 Bernard Stahl The Meaning of Humility Page 41 Murray Sragow “Jews and Booze—A look at Jewish responses to Prohibition” Page 49 Mark Teicher “Intertextuality/Numerology” Page 50 Mark Zitter ”קרבנות של חג השבועות“ 2 Forward by Rabbi Adler Chaveireinu HaYikarim, Every year on the first night of Shavuot many of us get together for the purpose of learning with one another. There are multiple shiurim and many hours of chavruta learning . Unfortunately, in today’s climate we cannot learn with one another but we can learn from one another. Enclosed are a variety of Torah articles on many different topics which you are invited to enjoy during the course of Zman Matan Torahteinu. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

אוסף מרמורשטיין the Marmorstein Collection

אוסף מרמורשטיין The Marmorstein Collection Brad Sabin Hill THE JOHN RYLANDS LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER Manchester 2017 1 The Marmorstein Collection CONTENTS Acknowledgements Note on Bibliographic Citations I. Preface: Hebraica and Judaica in the Rylands -Hebrew and Samaritan Manuscripts: Crawford, Gaster -Printed Books: Spencer Incunabula; Abramsky Haskalah Collection; Teltscher Collection; Miscellaneous Collections; Marmorstein Collection II. Dr Arthur Marmorstein and His Library -Life and Writings of a Scholar and Bibliographer -A Rabbinic Literary Family: Antecedents and Relations -Marmorstein’s Library III. Hebraica -Literary Periods and Subjects -History of Hebrew Printing -Hebrew Printed Books in the Marmorstein Collection --16th century --17th century --18th century --19th century --20th century -Art of the Hebrew Book -Jewish Languages (Aramaic, Judeo-Arabic, Yiddish, Others) IV. Non-Hebraica -Greek and Latin -German -Anglo-Judaica -Hungarian -French and Italian -Other Languages 2 V. Genres and Subjects Hebraica and Judaica -Bible, Commentaries, Homiletics -Mishnah, Talmud, Midrash, Rabbinic Literature -Responsa -Law Codes and Custumals -Philosophy and Ethics -Kabbalah and Mysticism -Liturgy and Liturgical Poetry -Sephardic, Oriental, Non-Ashkenazic Literature -Sects, Branches, Movements -Sex, Marital Laws, Women -History and Geography -Belles-Lettres -Sciences, Mathematics, Medicine -Philology and Lexicography -Christian Hebraism -Jewish-Christian and Jewish-Muslim Relations -Jewish and non-Jewish Intercultural Influences -

Musical Instruments and Recorded Music As Part of Shabbat and Festival Worship

Musical Instruments and Recorded Music as Part of Shabbat and Festival Worship Rabbis Elie Kaplan Spitz and Elliot N. Dorff Voting Draft - 2010. She’alah: May we play musical instruments or use recorded music on Shabbat and hagim as part of synagogue worship? If yes, what are the limitations regarding the following: 1. Repairing a broken string or reed 2. Tuning string or wind instruments 3. Playing electrical instruments and using prerecorded music 4. Carrying the instrument 5. Blowing the shofar 6. Qualifications and pay of musicians I. Introduction The use of musical instruments as an accompaniment to services on Shabbat and sacred holidays (yom tov) is increasing among Conservative synagogues. During a recent United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism’s biennial conference, a Shabbat worship service included singing the traditional morning prayers with musician accompaniment on guitar and electronic keyboard.1 Previously, a United Synagogue magazine article profiled a synagogue as a model of success that used musical instruments to enliven its Shabbat services.2 The matter-of-fact presentation written by its spiritual leader did not suggest any tension between the use of musical instruments and halakhic norms. While as a movement we have approved the use of some instruments on Shabbat, such as the organ, we remain in need of guidelines to preserve the sanctity of the holy days. Until now, the CJLS (Committee of Jewish Law and Standards) has not analyzed halakhic questions that relate to string and wind instruments, such as 1 See “Synagogues Become Rock Venues: Congregations Using Music to Revitalize Membership Rolls,” by Rebecca Spence, Forward, January 4, 2008, A3. -

Wrestling Demons

WRESTLING WITH DEMONS A History of Rabbinic Attitudes to Demons Natan Slifkin Copyright © 2011 by Natan Slifkin Version 1.0 http://www.ZooTorah.com http://www.RationalistJudaism.com This monograph is adapted from an essay that was written as part of the course requirements for a Master’s degree in Jewish Studies at the Lander Institute (Jerusalem). This document may be purchased at www.rationalistjudaism.com Other monographs available in this series: Messianic Wonders and Skeptical Rationalists The Evolution of the Olive Shiluach HaKein: The Transformation of a Mitzvah The Question of the Kidney’s Counsel The Sun’s Path at Night Sod Hashem Liyreyav: The Expansion of a Useful Concept Cover Illustration: The Talmud describes how King Solomon spoke with demons. This illustration is from Jacobus de Teramo’s Das Buch Belial (Augsburg 1473). 2 WRESTLING WITH DEMONS Introduction From Scripture to Talmud and Midrash through medieval Jewish writings, we find mention of dangerous and evil beings. Scripture refers to them as Azazel and se’irim; later writings refer to them as sheidim, ruchot and mazikim. All these are different varieties (or different names) of demons. Belief in demons (and the associated belief in witches, magic and occult phenomena) was widespread in the ancient world, and the terror that it caused is unimaginable to us.1 But in the civilized world today there is virtually nobody who still believes in them. The transition from a global approach of belief to one of disbelief began with Aristotle, gained a little more traction in the early medieval period, and finally concretized in the eighteenth century.