Armageddon at the Millennial Dawn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12 Monkeys Episode Guide Episodes 001–036

12 Monkeys Episode Guide Episodes 001–036 Last episode aired Sunday May 21, 2017 www.syfy.com c c 2017 www.tv.com c 2017 www.syfy.com c 2017 www.imdb.com c 2017 www.nerdist.com c 2017 www.ew.com The summaries and recaps of all the 12 Monkeys episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and http: //www.syfy.com and http://www.imdb.com and http://www.nerdist.com and http://www.ew.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ^¨ This booklet was LATEXed on June 28, 2017 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.59 Contents Season 1 1 1 Splinter . .3 2 Mentally Divergent . .5 3 Cassandra Complex . .7 4 Atari...............................................9 5 The Night Room . 11 6 The Red Forest . 13 7 The Keys . 15 8 Yesterday . 17 9 Tomorrow . 19 10 Divine Move . 23 11 Shonin . 25 12 Paradox . 27 13 Arms of Mine . 29 Season 2 31 1 Year of the Monkey . 33 2 Primary . 35 3 One Hundred Years . 37 4 Emergence . 39 5 Bodies of Water . 41 6 Immortal . 43 7 Meltdown . 45 8 Lullaby . 47 9 Hyena.............................................. 49 10 Fatherland . 51 11 Resurrection . 53 12 Blood Washed Away . 55 13 Memory of Tomorrow . 57 Season 3 59 1 Mother . 61 2 Guardians . 63 3 Enemy.............................................. 65 4 Brothers . 67 5 Causality . 69 6 Nature.............................................. 71 7 Nurture . 73 8 Masks.............................................. 75 9 Thief............................................... 77 10 Witness -

Deep Impact As a World Observatory Event Held in Brussels, Belgium, 7–10 August 2006

Other Astronomical News Report on the Workshop on Deep Impact as a World Observatory Event held in Brussels, Belgium, 7–10 August 2006 Hans Ulrich Käufl1 One of the spectacular deconvolved images from the Christiaan Sterken2 Deep Impact Spacecraft High Resolution Imager shown in the conference (courtesy Mike A’Hearn and the Deep Impact Team). This is a colour composite of an infrared, a green and a violet filter forced to av- 1 ESO erage grey. Note the blueish areas on the surface 2 Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium close to the crater-like structure. Those were entirely unexpected. It is highly interesting to find out if those structures can be correlated with the jets which were meticulously monitored from ground-based ob- In the context of NASA’s Deep Impact servers worldwide. This aspect in the picture – en- space mission, Comet 9P/Tempel1 tirely unrelated to the impact plume – illustrates very well how comet research, apart from the impact has been at the focus of an unprece- experiment, will profit from the synergy of spacecraft dented worldwide long-term multi- data and the unprecedented worldwide coordinated wavelength observation campaign. The observing campaign. comet has been studied through its perihelion passage by various spacecraft including the Deep Impact mission it- self, HST, Spitzer, Rosetta, XMM and all To make full use of the global data set, a To inspire new ideas, it was very helpful major ground-based observatories in workshop bringing together observers and interesting to have Roberta Olson basically all wavelength bands used in across the electromagnetic spectrum and from the New York Historical Society, astronomy, i.e. -

Size of Particles Ejected from an Artificial Impact Crater on Asteroid

A&A 647, A43 (2021) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202039777 & © K. Wada et al. 2021 Astrophysics Size of particles ejected from an artificial impact crater on asteroid 162173 Ryugu K. Wada1, K. Ishibashi1, H. Kimura1, M. Arakawa2, H. Sawada3, K. Ogawa2,4, K. Shirai2, R. Honda5, Y. Iijima3, T. Kadono6, N. Sakatani7, Y. Mimasu3, T. Toda3, Y. Shimaki3, S. Nakazawa3, H. Hayakawa3, T. Saiki3, Y. Takagi8, H. Imamura3, C. Okamoto2, M. Hayakawa3, N. Hirata9, and H. Yano3 1 Planetary Exploration Research Center, Chiba Institute of Technology, Narashino 275-0016, Japan e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Planetology, Kobe University, Kobe 657-8501, Japan 3 Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, Sagamihara 252-5210, Japan 4 JAXA Space Exploration Center, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, Sagamihara 252-5210, Japan 5 Department of Science and Technology, Kochi University, Kochi 780-8520, Japan 6 Department of Basic Sciences, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Kitakyusyu 807-8555, Japan 7 Department of Physics, Rikkyo University, Tokyo 171-8501, Japan 8 Aichi Toho University, Nagoya 465-8515, Japan 9 School of Computer Science and Engineering, The University of Aizu, Aizu-Wakamatsu 965-8580, Japan Received 28 October 2020 / Accepted 26 January 2021 ABSTRACT A projectile accelerated by the Hayabusa2 Small Carry-on Impactor successfully produced an artificial impact crater with a final apparent diameter of 14:5 0:8 m on the surface of the near-Earth asteroid 162173 Ryugu on April 5, 2019. At the time of cratering, Deployable Camera 3 took± clear time-lapse images of the ejecta curtain, an assemblage of ejected particles forming a curtain-like structure emerging from the crater. -

A Ballistics Analysis of the Deep Impact Ejecta Plume: Determining Comet Tempel 1’S Gravity, Mass, and Density

Icarus 190 (2007) 357–390 www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus A ballistics analysis of the Deep Impact ejecta plume: Determining Comet Tempel 1’s gravity, mass, and density James E. Richardson a,∗,H.JayMeloshb, Carey M. Lisse c, Brian Carcich d a Center for Radiophysics and Space Research, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA b Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721-0092, USA c Planetary Exploration Group, Space Department, Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, 11100 Johns Hopkins Road, Laurel, MD 20723, USA d Center for Radiophysics and Space Research, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA Received 31 March 2006; revised 8 August 2007 Available online 15 August 2007 Abstract − In July of 2005, the Deep Impact mission collided a 366 kg impactor with the nucleus of Comet 9P/Tempel 1, at a closing speed of 10.2 km s 1. In this work, we develop a first-order, three-dimensional, forward model of the ejecta plume behavior resulting from this cratering event, and then adjust the model parameters to match the flyby-spacecraft observations of the actual ejecta plume, image by image. This modeling exercise indicates Deep Impact to have been a reasonably “well-behaved” oblique impact, in which the impactor–spacecraft apparently struck a small, westward-facing slope of roughly 1/3–1/2 the size of the final crater produced (determined from initial ejecta plume geometry), and possessing an effective strength of not more than Y¯ = 1–10 kPa. The resulting ejecta plume followed well-established scaling relationships for cratering in a medium-to-high porosity target, consistent with a transient crater of not more than 85–140 m diameter, formed in not more than 250–550 s, for the case of Y¯ = 0 Pa (gravity-dominated cratering); and not less than 22–26 m diameter, formed in not less than 1–3 s, for the case of Y¯ = 10 kPa (strength-dominated cratering). -

The Military Guide to Armageddon • D

The Military Guide to Armageddon • D. Giamonna, T. Anderson Chosen Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group © 2021 used by permission BATTLE- TESTED STRATEGIES TO PREPARE YOUR LIFE AND SOUL FOR THE END TIMES COL. DAVID J. GIAMMONA AND TROY ANDERSON G The Military Guide to Armageddon • D. Giamonna, T. Anderson Chosen Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group © 2021 used by permission _Giammona_MilitaryGuide_ET_bb.indd 3 10/1/20 8:02 AM 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 © 2021 by David J. Giammona and Troy Anderson Published by Chosen Books 11400 Hampshire Avenue South Bloomington, Minnesota 55438 www.chosenbooks.com Chosen Books is a division of Baker Publishing Group, Grand Rapids, Michigan Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means— for example, electronic, photocopy, recording— without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Giammona, David J., author. | Anderson, Troy (Journalist), author. Title: The military guide to Armageddon: battle-tested strategies to prepare your life and soul for the end times / Col. David J. Giammona and Troy Anderson. Description: Minneapolis, Minnesota: Chosen Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2020038021 | ISBN 9780800761943 (paperback) | ISBN 9780800762261 (casebound) | ISBN 9781493430086 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Spiritual warfare. | End of the world. | Armageddon. Classification: LCC BV4509.5 .G466 2021 | DDC 236/.9—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020038021 Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from THE HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. -

EPOXI COMET ENCOUNTER FACT SHEET Nov

EPOXI COMET ENCOUNTER FACT SHEET Nov. 2, 2010 Quick Facts Flyby Spacecraft Dimensions: 3.3 meters (10.8 feet) long, 1.7 meters (5.6 feet) wide, and 2.3 meters (7.5 feet) high Weight: 601 kilograms (1,325 pounds) at launch, consisting of 517 kilograms (1,140 pounds) spacecraft and 84 kilograms (185 pounds) fuel. On 10/25/10 there was 4 kilograms (8.8 pounds) of fuel remaining. Power: 2.8-meter-by-2.8-meter (9-foot-by-9 foot) solar panel providing up to 750 watts, depending on distance from sun. Power storage via small, 16-amp- hourrechargeable nickel hydrogen battery Comet Hartley 2 Nucleus shape: Elongated Nucleus size (estimated): About 2.2 kilometers (1.4 miles) long Nucleus mass: Roughly 280 million metric tons Nucleus rotation period: About 18 hours Nucleus composition: Water ice, carbon dioxide ice, silicate dust Mission Launch: Jan. 12, 2005 Launch site: Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida Launch vehicle: Delta II 7925 with Star 48 upper stage Impact with Tempel 1: 10:52 p.m. PDT July 3, 2005 (1:52 a.m. EDT July 4, 2005) Earth-comet distance at time of impact: 133.6 million kilometers (83 million miles) Total distance traveled by spacecraft from Earth to Tempel 1: 431 million kilometers (268 million miles) Flyby of Hartley 2: About 10 a.m. EDT or 7 a.m. PDT Nov. 4, 2010 Additional distance traveled by spacecraft to Hartley 2: About 4.6 billion kilometers (2.9 billion miles) Program Cost of Deep Impact: $267 million total (not including launch vehicle), consisting of $252 million spacecraft development and $15 million mission operations Cost of EPOXI extended mission: $42 million, for operations from 2007 to end of project at the end of fiscal year 2011. -

Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

598 CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia A. GRAY READ University of Pennsylvania Fictional images ofreal places in novels and films shadow the city as a trickster, doubling its architecture in stories that make familiar places seem strange. In the opening sequence of Terry Gilliam's recent film, 12 Monkeys, the hero, Bruce Willis,rises fromunderground in the year 2027, toexplore the ruined city of Philadelphia, abandoned in late 1997, now occupied by large animals liberated from the zoo. The image is uncanny, particularly for those familiar with the city, encouraging a suspicion that perhaps Philadelphia is, after all, an occupied ruin. In an instant of recognition, the movie image becomes part of Philadelphia and the real City Hall becomes both more nostalgic and decrepit. Similarly, the real streets of New York become more threatening in the wake of a film like Martin Scorcese's Taxi driver and then more ironic and endearing in the flickering light ofWoody Allen's Manhattan. Physical experience in these cities is Fig. 1. Philadelphia's City Hall as a ruin in "12 Monkeys." dense with sensation and memories yet seized by references to maps, books, novels, television, photographs etc.' In Philadelphia, the breaking of class boundaries (always a Gilliam's image is false; Philadelphia is not abandoned, narrative opportunity) is dramatic to the point of parody. The yet the real city is seen again, through the story, as being more early twentieth century saw a distinct Philadelphia genre of or less ruined. Fiction is experimental life tangent to lived novels with a standard plot: a well-to-do heir falls in love with experience that scouts new territories for the imagination.' a vivacious working class woman and tries to bring her into Stories crystallize and extend impressions of the city into his world, often without success. -

Millennialism, Rapture and “Left Behind” Literature. Analysing a Major Cultural Phenomenon in Recent Times

start page: 163 Stellenbosch Theological Journal 2019, Vol 5, No 1, 163–190 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2019.v5n1.a09 Online ISSN 2413-9467 | Print ISSN 2413-9459 2019 © Pieter de Waal Neethling Trust Millennialism, rapture and “Left Behind” literature. Analysing a major cultural phenomenon in recent times De Villers, Pieter GR University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa [email protected] Abstract This article represents a research overview of the nature, historical roots, social contexts and growth of millennialism as a remarkable religious and cultural phenomenon in modern times. It firstly investigates the notions of eschatology, millennialism and rapture that characterize millennialism. It then analyses how and why millennialism that seems to have been a marginal phenomenon, became prominent in the United States through the evangelistic activities of Darby, initially an unknown pastor of a minuscule faith community from England and later a household name in the global religious discourse. It analyses how millennialism grew to play a key role in the religious, social and political discourse of the twentieth century. It finally analyses how Darby’s ideas are illuminated when they are placed within the context of modern England in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth century. In a conclusion some key challenges of the place and role of millennialism as a movement that reasserts itself continuously, are spelled out in the light of this history. Keywords Eschatology; millennialism; chiliasm; rapture; dispensationalism; J.N. Darby; Joseph Mede; Johann Heinrich Alsted; “Left Behind” literature. 1. Eschatology and millennialism Christianity is essentially an eschatological movement that proclaims the fulfilment of the divine promises in Hebrew Scriptures in the earthly ministry of Christ, but it also harbours the expectation of an ultimate fulfilment of Christ’s second coming with the new world of God that will replace the existing evil dispensation. -

Key Scriptures: Revelation 19:1-21 Ezekiel 38 & 39 Joel 2:1-11

God's Master Plan In Prophecy Lesson 13 – The Battle of Armageddon & 2nd Coming of Jesus Christ Key Scriptures: Revelation 19:1-21 Ezekiel 38 & 39 Joel 2:1-11 Zechariah 12-14 Introduction Rev 19:1 After these things I heard something like a loud voice of a great multitude in heaven, saying, "Hallelujah! Salvation and glory and power belong to our God; While the Wrath of God is being poured out, there was the voice of "a great multitude in heaven" praising God! This is the redeemed church which has missed the Wrath of God and was taken out of Great Tribulation. While the earth is experiencing the judgment of God without mercy, we are experiencing His goodness without judgment! Rev 19:2-3 BECAUSE HIS JUDGMENTS ARE TRUE AND RIGHTEOUS; for He has judged the great harlot who was corrupting the earth with her immorality, and HE HAS AVENGED THE BLOOD OF HIS BOND-SERVANTS ON HER." 3 And a second time they said, "Hallelujah! HER SMOKE RISES UP FOREVER AND EVER." From what is being said in these verse, it is obvious that the church will be fully aware of what is happening upon the earth during this time, yet because we are no longer viewing earth's events through the eyes of mortal flesh, we will understand that God is righteous and true in His judgments. To modern minds it may seem strange to worship and say, “hallelujah” over the fact that God is pouring out judgment, but that is because we see imperfectly now. -

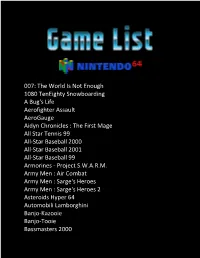

007: the World Is Not Enough 1080 Teneighty Snowboarding a Bug's

007: The World Is Not Enough 1080 TenEighty Snowboarding A Bug's Life Aerofighter Assault AeroGauge Aidyn Chronicles : The First Mage All Star Tennis 99 All-Star Baseball 2000 All-Star Baseball 2001 All-Star Baseball 99 Armorines - Project S.W.A.R.M. Army Men : Air Combat Army Men : Sarge's Heroes Army Men : Sarge's Heroes 2 Asteroids Hyper 64 Automobili Lamborghini Banjo-Kazooie Banjo-Tooie Bassmasters 2000 Batman Beyond : Return of the Joker BattleTanx BattleTanx - Global Assault Battlezone : Rise of the Black Dogs Beetle Adventure Racing! Big Mountain 2000 Bio F.R.E.A.K.S. Blast Corps Blues Brothers 2000 Body Harvest Bomberman 64 Bomberman 64 : The Second Attack! Bomberman Hero Bottom of the 9th Brunswick Circuit Pro Bowling Buck Bumble Bust-A-Move '99 Bust-A-Move 2: Arcade Edition California Speed Carmageddon 64 Castlevania Castlevania : Legacy of Darkness Chameleon Twist Chameleon Twist 2 Charlie Blast's Territory Chopper Attack Clay Fighter : Sculptor's Cut Clay Fighter 63 1-3 Command & Conquer Conker's Bad Fur Day Cruis'n Exotica Cruis'n USA Cruis'n World CyberTiger Daikatana Dark Rift Deadly Arts Destruction Derby 64 Diddy Kong Racing Donald Duck : Goin' Qu@ckers*! Donkey Kong 64 Doom 64 Dr. Mario 64 Dual Heroes Duck Dodgers Starring Daffy Duck Duke Nukem : Zero Hour Duke Nukem 64 Earthworm Jim 3D ECW Hardcore Revolution Elmo's Letter Adventure Elmo's Number Journey Excitebike 64 Extreme-G Extreme-G 2 F-1 World Grand Prix F-Zero X F1 Pole Position 64 FIFA 99 FIFA Soccer 64 FIFA: Road to World Cup 98 Fighter Destiny 2 Fighters -

Antichrist As (Anti)Charisma: Reflections on Weber and the ‘Son of Perdition’

Religions 2013, 4, 77–95; doi:10.3390/rel4010077 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article Antichrist as (Anti)Charisma: Reflections on Weber and the ‘Son of Perdition’ Brett Edward Whalen Department of History, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB# 3193, Chapel Hill, NC, 27707, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-919-962-2383 Received: 20 December 2012; in revised form: 25 January 2013 / Accepted: 29 January 2013 / Published: 4 February 2013 Abstract: The figure of Antichrist, linked in recent US apocalyptic thought to President Barack Obama, forms a central component of Christian end-times scenarios, both medieval and modern. Envisioned as a false-messiah, deceptive miracle-worker, and prophet of evil, Antichrist inversely embodies many of the qualities and characteristics associated with Max Weber’s concept of charisma. This essay explores early Christian, medieval, and contemporary depictions of Antichrist and the imagined political circumstances of his reign as manifesting the notion of (anti)charisma, compelling but misleading charismatic political and religious leadership oriented toward damnation rather than redemption. Keywords: apocalypticism; charisma; Weber; antichrist; Bible; US presidency 1. Introduction: Obama, Antichrist, and Weber On 4 November 2012, just two days before the most recent US presidential election, Texas “Megachurch” pastor Robert Jeffress (1956– ) proclaimed that a vote for the incumbent candidate Barack Obama (1961– ) represented a vote for the coming of Antichrist. “President Obama is not the Antichrist,” Jeffress qualified to his listeners, “But what I am saying is this: the course he is choosing to lead our nation is paving the way for the future reign of Antichrist” [1]. -

The Rapture in Twenty Centuries of Biblical Interpretation

TMSJ 13/2 (Fall 2002) 149-171 THE RAPTURE IN TWENTY CENTURIES OF BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION James F. Stitzinger Associate Professor of Historical Theology The coming of God’s Messiah deserves closer attention than it has often received. The future coming of the Messiah, called the “rapture,” is imminent, literal and visible, for all church saints, before the hour of testing, premillennial, and, based on a literal hermeneutic, distinguishes between Israel and the church. The early church fathers’ views advocated a sort of imminent intra- or post- tribulationism in connection with their premillennial teaching. With a few exceptions, the Medieval church writers said little about a future millennium and a future rapture. Reformation leaders had little to say about prophetic portions of Scripture, but did comment on the imminency of Christ’s return. The modern period of church history saw a return to the early church’s premillennial teaching and a pretribulational rapture in the writings of Gill and Edwards, and more particularly in the works of J. N. Darby. After Darby, pretribulationism spread rapidly in both Great Britain and the United States. A resurgence of posttribulationism came after 1952, accompanied by strong opposition to pretribulationism, but a renewed support of pretribulationism has arisen in the recent past. Five premillennial views of the rapture include two major views—pretribulationism and posttribulation-ism—and three minor views—partial, midtribulational, and pre-wrath rapturism. * * * * * Introduction The central theme of the Bible is the coming of God’s Messiah. Genesis 3:15 reveals the first promise of Christ’s coming when it records, “He shall bruise you on the head, And you shall bruise him on the heel.”1 Revelation 22:20 unveils the last promise when it records “He who testifies to these things says, ‘Yes, I am coming quickly,’ Amen.