The Burden of Security Moral Frictions and Everyday Policing in a Contested Religious Compound

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Introduction: Siting and Experiencing Divinity in Bengal

chapter 1 Introduction : Siting and Experiencing Divinity in Bengal-Vaishnavism background The anthropology of Hinduism has amply established that Hindus have a strong involvement with sacred geography. The Hindu sacred topography is dotted with innumerable pilgrimage places, and popu- lar Hinduism is abundant with spatial imaginings. Thus, Shiva and his partner, the mother goddess, live in the Himalayas; goddesses descend to earth as beautiful rivers; the goddess Kali’s body parts are imagined to have fallen in various sites of Hindu geography, sanctifying them as sacred centers; and yogis meditate in forests. Bengal similarly has a thriving culture of exalting sacred centers and pilgrimage places, one of the most important being the Navadvip-Mayapur sacred complex, Bengal’s greatest site of guru-centered Vaishnavite pilgrimage and devo- tional life. While one would ordinarily associate Hindu pilgrimage cen- ters with a single place, for instance, Ayodhya, Vrindavan, or Banaras, and while the anthropology of South Asian pilgrimage has largely been single-place-centered, Navadvip and Mayapur, situated on opposite banks of the river Ganga in the Nadia District of West Bengal, are both famous as the birthplace(s) of the medieval saint, Chaitanya (1486– 1533), who popularized Vaishnavism on the greatest scale in eastern India, and are thus of massive simultaneous importance to pilgrims in contemporary Bengal. For devotees, the medieval town of Navadvip represents a Vaishnava place of antique pilgrimage crammed with cen- turies-old temples and ashrams, and Mayapur, a small village rapidly 1 2 | Chapter 1 developed since the nineteenth century, contrarily represents the glossy headquarters site of ISKCON (the International Society for Krishna Consciousness), India’s most famous globalized, high-profile, modern- ized guru movement. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

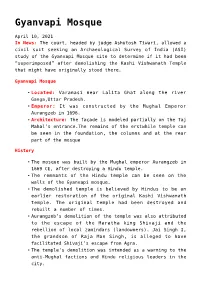

Gyanvapi Mosque

Gyanvapi Mosque April 10, 2021 In News: The court, headed by judge Ashutosh Tiwari, allowed a civil suit seeking an Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) study of the Gyanvapi Mosque site to determine if it had been “superimposed” after demolishing the Kashi Vishwanath Temple that might have originally stood there. Gyanvapi Mosque Located: Varanasi near Lalita Ghat along the river Ganga,Uttar Pradesh. Emperor: It was constructed by the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb in 1696. Architecture: The façade is modeled partially on the Taj Mahal’s entrance.The remains of the erstwhile temple can be seen in the foundation, the columns and at the rear part of the mosque History The mosque was built by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in 1669 CE, after destroying a Hindu temple. The remnants of the Hindu temple can be seen on the walls of the Gyanvapi mosque. The demolished temple is believed by Hindus to be an earlier restoration of the original Kashi Vishwanath temple. The original temple had been destroyed and rebuilt a number of times. Aurangzeb’s demolition of the temple was also attributed to the escape of the Maratha king Shivaji and the rebellion of local zamindars (landowners). Jai Singh I, the grandson of Raja Man Singh, is alleged to have facilitated Shivaji’s escape from Agra. The temple’s demolition was intended as a warning to the anti-Mughal factions and Hindu religious leaders in the city. Kashi Vishwanath Temple Hindu temples dedicated to Lord Shiva. It is located in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh. The Temple stands on the western bank of the holy river Ganga, and is one of the twelve Jyotirlingas, or Jyotirlingams, the holiest of Shiva Temples. -

Registration Form

REGISTRATION FORM Title: Prof./Dr./Mr./Ms. ……………. Name:………………………………………. Designation:…………………..Organization/Institution:……………………………………… Address:………………………………………………………………………..………………… City :…………………………… Postal code:…………………… Country:…………………... E-mail …………………………….. Mobile ………………………….. Tel …………………… Name of accompanying person(s) (if any) :………………………………………………. For foreign delegates only Nationality…………… Passport No.: ………………Date and Place of issue …………… Registration fee The registration fee includes conference kit, access to inaugural function, scientific sessions, exhibitions, lunch, dinner and session tea. Category Upto Aug 31, 2010 After Aug 31, 2010 On Spot Student* Rs. 1000 Rs. 1250 Rs. 1500 Faculty member Rs. 1500 Rs. 1750 Rs. 2000 Accompanying person** Rs. 750 Rs. 1000 Rs. 1250 Foreign delegate USD 100 USD 125 USD 150 *Endorsement by the supervisor, **Excludes registration kit. Mode of Presentation (Indicate preference) Symposium Presentation by Young Scientists: Oral /Poster (Size: 1mx1m) Broad Area:………………. Sub Area:……….. Title of presentation:……. Signature Date : Place: ACCOMMODATION FORM Limited accommodation is available on first come first serve basis to early registered participants in the guest house (Rs.400/- per night). Hotel accommodation is also available and may be booked directly or through travel agents (Email:[email protected]). As November is the festival season, the city is full of tourists. It will be difficult to arrange accommodation without advance payment and for those registered late. Name………………..…………………………………………. -

Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Nandrajog, Elaisha, "Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010)" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 219. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/219 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE HINDUTVA AND ANTI-MUSLIM COMMUNAL VIOLENCE IN INDIA UNDER THE BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY (1990-2010) SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR RODERIC CAMP AND PROFESSOR GASTÓN ESPINOSA AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ELAISHA NANDRAJOG FOR SENIOR THESIS (Spring 2010) APRIL 26, 2010 2 CONTENTS Preface 02 List of Abbreviations 03 Timeline 04 Introduction 07 Chapter 1 13 Origins of Hindutva Chapter 2 41 Setting the Stage: Precursors to the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 3 60 Bharat : The India of the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 4 97 Mosque or Temple? The Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi Dispute Chapter 5 122 Modi and his Muslims: The Gujarat Carnage Chapter 6 151 Legalizing Communalism: Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (2002) Conclusion 166 Appendix 180 Glossary 185 Bibliography 188 3 PREFACE This thesis assesses the manner in which India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as the political face of Hindutva, or Hindu ethno-cultural nationalism. The insights of scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot, Ashish Nandy, Thomas Blom Hansen, Ram Puniyani, Badri Narayan, and Chetan Bhatt have been instrumental in furthering my understanding of the manifold elements of Hindutva ideology. -

Ayodhya Page:- 1 Cent-Code & Name Exam Sch-Status School Code & Name #School-Allot Sex Part Group 1003 Canossa Convent Girls Inter College Ayodhya Buf

DATE:27-02-2021 BHS&IE, UP EXAM YEAR-2021 **** FINAL CENTRE ALLOTMENT REPORT **** DIST-CD & NAME :- 62 AYODHYA PAGE:- 1 CENT-CODE & NAME EXAM SCH-STATUS SCHOOL CODE & NAME #SCHOOL-ALLOT SEX PART GROUP 1003 CANOSSA CONVENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA BUF HIGH BUF 1001 SAHABDEENRAM SITARAM BALIKA I C AYODHYA 73 F HIGH BUF 1003 CANOSSA CONVENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 225 F 298 INTER BUF 1002 METHODIST GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 56 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER BUF 1003 CANOSSA CONVENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 109 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER BUF 1003 CANOSSA CONVENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 111 F SCIENCE INTER CUM 1091 DARSGAH E ISLAMI INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 53 F ALL GROUP 329 CENTRE TOTAL >>>>>> 627 1004 GOVT GIRLS I C GOSHAIGANJ AYODHYA AUF HIGH AUF 1004 GOVT GIRLS I C GOSHAIGANJ AYODHYA 40 F HIGH CRF 1125 VIDYA DEVIGIRLS I C ANKARIPUR AYODHYA 11 F HIGH CRM 1140 SARDAR BHAGAT SINGH HS BARAIPARA DULLAPUR AYODHYA 20 F HIGH CRM 1208 M D M N ARYA HSS R N M G GANJ AYODHYA 7 F HIGH CUM 1265 A R A IC K GADAR RD GOSAINGANJ AYODHYA 32 F HIGH CRM 1269 S S M HSS K G ROAD GOSHAINGANJ AYODHYA 26 F HIGH CRM 1276 IMAMIA H S S AMSIN AYODHYA 15 F HIGH AUF 5004 GOVT GIRLS I C GOSHAIGANJ AYODHYA 18 F 169 INTER AUF 1004 GOVT GIRLS I C GOSHAIGANJ AYODHYA 43 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRF 1075 MADHURI GIRLS I C AMSIN AYODHYA 91 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRF 1125 VIDYA DEVIGIRLS I C ANKARIPUR AYODHYA 7 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRM 1138 AMIT ALOK I C BODHIPUR AMSIN AYODHYA 96 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CUM 1265 A R A IC K GADAR RD GOSAINGANJ AYODHYA 74 -

Royal Valley Tourism

Royal Valley Tourism https://www.indiamart.com/royal-valley-tourismudaipur/ Royal Valley Tourism is an Indo-French Tour Operator based in India offering general and specialised travel services across India, Nepal and Bhutan. Planning a travel with RVT ensures quality, reliability, service, efficiency and perhaps most ... About Us Royal Valley Tourism is an Indo-French Tour Operator based in India offering general and specialised travel services across India, Nepal and Bhutan. Planning a travel with RVT ensures quality, reliability, service, efficiency and perhaps most important competitive pricing. RVT has branch and associate offices at major tourist destinations of India, Nepal and Bhutan. Our personalised services guratees complete peace of mind. Our staff has a high average of experience in the travel business. We have specialists in all major aspects of travel, multilingual of course. Royal Valley Tourism has a qualified guide staff who are trained naturalists, skilled in translating complex scientific information or ancient history into interesting and easily understandable terms. We offer a comprehensive range of services, which is sure to match all your specific requirements: - Specialize in handling Incoming Tours including individuals and Group travelers, delegations and charters. - Transfers, Sightseeing and excursions. - Air and Train reservations. - Services of multilingual Guides & Escorts - Hotel bookings & Confirmations - Transport hire. - Wedding packages - Conferences & Meetings - Group and private guided excursions. -

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 As of June, 2009

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 as of June, 2009 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male TOTAL District 321 E 25961 ALLAHABAD 10 11 9 16 25 District 321 E 25962 ALLAHABAD GREATER 8 4 8 20 28 District 321 E 26002 MIRZAPUR 19 22 19 57 76 District 321 E 26013 RENUKOOT 1 1 1 167 168 District 321 E 26021 VARANASI 4 4 4 56 60 District 321 E 30064 BASTI 0 0 0 21 21 District 321 E 30994 VARANASI VISHAL 18 18 18 28 46 District 321 E 31402 RENUSAGAR 3 2 2 62 64 District 321 E 31514 ROBERTSGANJ 0 0 0 25 25 District 321 E 35103 VARANASI GANGA 0 0 1 59 60 District 321 E 36259 ALLAHABAD CENTRAL 2 6 10 14 24 District 321 E 38098 VARANASI VARUNA 0 0 0 33 33 District 321 E 38880 GORAKHPUR VISHAL 2 2 3 16 19 District 321 E 40468 GORAKHPUR RAPTI 0 0 0 21 21 District 321 E 43275 ROBERTSGANJ KAIMOORE 12 0 1 15 16 District 321 E 45215 JAUNPUR 3 0 0 58 58 District 321 E 45467 VARANASI SHIVA 0 0 1 18 19 District 321 E 45953 SULTANPUR CENTRAL 0 0 0 27 27 District 321 E 46981 BHADOHI VARUNA 1 1 20 30 50 District 321 E 48896 GORAKHPUR GEETA 0 0 0 13 13 District 321 E 49039 ALLAHABAD CITY 32 57 110 227 337 District 321 E 49383 ALLAHABAD ADARSH 18 18 18 23 41 District 321 E 49956 ALLAHABAD EVES 0 0 34 1 35 District 321 E 49998 VARANASI SURYA 0 0 1 19 20 District 321 E 51013 ALLAHABAD CANTT 7 9 11 23 34 District 321 E 51494 VARANASI CITY 0 0 0 34 34 District 321 E 51583 JAUNPUR GOMTI 0 0 0 40 40 District 321 E 51689 MORWA 0 0 0 31 31 District 321 E 54995 VARANASI RUDRA 9 0 0 16 16 District -

Silver Sky Travel World

UTTAR PRADESH MAUJ 5 NIGHTS / 6 DAYS ( 1 NIGHT VARANASI , 1 NIGHT BODHGAYA , 1 NIGHT VARANASI , 1 NIGHT AYODHYA , 1 NIGHT ALLAHABAD Description For India, Uttar Pradesh has a great importance as elections in UP, India's most populous province, marks a significant impact on the Central government's performance. ... Uttar Pradesh is the third largest Indian state by economy, with a GDP of ?9763 billion (US$140 billion). Tour Highlights VARANASI: Varanasi is the oldest living city in the world.The land of Varanasi (Kashi) has been the ultimate pilgrimage spot for Hindus for ages.Hindus believe that one who is graced to die on the land of Varanasi would attain salvation and freedom from the cycle of birth and re-birth. BODHGAYA : Bodh Gaya is a religious site and place of pilgrimage associated with the Mahabodhi Temple Complex in Gaya district in the Indian state of Bihar. It is famous as it is the place where Gautama Buddha is said to have obtained Enlightenment (pali: bodhi) under what became known as the Bodhi Tree. ALLAHABAD: The ancient name of the city is Prayag (Sanskrit for "place of sacrifice"), as it is believed to be the spot where Brahma Page 1/7 offered his first sacrifice after creating the world. Since its founding, Prayaga renamed Allahabad has played an important role in the history and cultural life of India. obtained Enlightenment (pali: bodhi) under what became known as the Bodhi Tree. Attractions and Shopping Tips VARANASI : Ganges , Kashi Vishwanath Temple , Dashashwamedh Ghat , Ramnagar Fort , Assi Ghat , VARANASI SHOPPING TIPS :Banarasi saris , Musical instruments , Brassware BODH GAYA :Bodhi Tree , Vishnupad Mandir BODH GAYA SHOPPING TIPS :Handicrafts such as sandal wood beads, wooden crafts and artifacts. -

Subject Index

Economic and Political Weekly INDEX Vol XLV Nos 1-52 January-December 2010 Ed = Editorials MMR = Money Market Review F = Feature RA= Review Article CL = Civil Liberties SA = Special Article C = Commentary D = Discussion P = Perspectives SS = Special Statistics BR = Book Review LE = Letters to Editor SUBJECT INDEX ACADEMICIANS Who Cares for the Railways? (Ed) Social Science Writing in Marathi; Mahesh Issue no: 30, Jul 24-30, p.08 Gavaskar (C) Issue no: 36, Sep 04-10, p.22 Worker Deaths; Moushumi Basu and Asish Gupta (LE) ACADEMY Issue no: 37, Sep 11-17, p.5 Noor Mohammed Bhatt; Moushumi Basu and Asish Gupta (LE) ADDICTION Issue no: 52, Dec 25-31, p.5 A Case for Opium Dens; Vithal Rajan (LE) ACCIDENTAL DEATHS Issue no: 18, May 01-07, p.5 The Bhopal Catastrophe: Politics, Conspiracy and Betrayal; Colin ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS Gonsalves (P) K N Raj and the Delhi School; J Issue no: 26-27, Jun 26-Jul 09, p.68 Krishnamurty (F) Issue no: 11, Mar 13-19, p.67 Bhopal Gas Leak Case: Lost before the Trial; Sriram Panchu (C) ADOPTION LAW Issue no: 25, Jun 19-25, p.10 Expanding Adoption Rights (Ed) Issue no: 35, Aug 28-Sep 03, p.8 Chronic Denial of Justice (LE) Issue no: 24, Jun 12-18, p.07 AFGHANISTAN Exposure of War Crimes (Ed) Conspiracy to Implicate Maoists; Azad Issue no: 31, Jul 31-Aug 06, p.08 (LE) Issue no: 24, Jun 12-18, p.05 AGRARIAN REFORMS A Critical Review of Agrarian Reforms Gyaneshwari Express Sabotage - I; Asish in Sikkim; Anjan Chakrabarti (C) Gupta and Moushumi Basu (LE) Issue no: 05, Jan 30-Feb 05, p.23 Issue no: 23, Jun 05-11, p.04 -

Lord Shiva in Varanasi Visual Processes and the Representation

OWE WIKSTRÖM Darsan (to See) Lord Shiva in Varanasi Visual Processes and the Representation of God by Seven Ricksha-Drivers Introduction In spite of its effort to be transculturally relevant, the psychology of relig- ion is quite ethno- or rather Western-centric. This becomes very clear when one tries to "translate" Indian folk religiosity into concepts taken from mainline theories; i.e. social, cognitive or psychoanalytical psychology of religion. Not only do the norms and values differ, but the very ontological assumptions underlying the categories in which the researcher understand differs fundamentally from the internal Hindu anthropological and epis- temiological apriori. For example, their words of the psyche include contex- tuality, from time to space, to ethics to groups. The subtle interrelatedness of the divine, spiritual and the mundane is obvious (Geertz 1973). It in- cludes the flows and exchanges of substances within and between persons with minimal outer bondaries. The psychological makeup of persons in societies so civilizationally dif- ferent as India is embedded in fundamentally distinct principles of these cultures and the social patterns and child rearing that these principles shape (Marsella et al 1985). Therefore it is clear that a western scholar and an Indian devotee are quite different, not only simply that they see things differently, coming from varied cultures, but that the very inner emotional- cognitive makeup is culturally constructed in different ways (Roland 1989). Of course this will "disturb" the interaction between interviewer and in- terviewee, the scholar and the pious man. In order to understand the psy- chological dynamics in folk religiosity, I think that the researcher has to re- examine and be aware of the way he uses the theoretical models in cross- cultural psychological hermeneutics. -

Death and Life on the Varanasi Ghats

KEY WORDS: Ghats, Ganga, Cultural Landscape, Natural Archetypes, Spatial Practices, Embodied Perception Death and Life on the Varanasi Ghats Amita Sinha Tekton Volume 4, Issue 2, September 2017 pp. 36 - 53 ABSTRACT The ghats of Varanasi have been sketched, painted and photographed endlessly, especially the panoramic view, popular since the nineteenth century. This ‘way of seeing’ Amita Sinha is a Professor in the reflects the Western picturesque convention and is associated Department of Landscape Architecture with the aesthetic experience residing in the view. I argue at the University of Illinois at Urbana that the idea of the landscape as a picturesque view does Champaign, USA. She is the author of not fully describe the experience in the ghats. Instead the Landscapes In India: Forms and Meanings cultural landscape should be interpreted as a ‘situated event’, (University Press of Colorado, 2006; of text enacted and performed, and experienced through all reprinted by Asia Educational Services, the senses. The sensual engagement of the body with the 2011) and editor of Landscape Perception landscape is the basis of feelings and emotions in embodied (Academic Press, 1995) and Natural perception. The spatial and formal design language of the Heritage of Delhi (USIEF and INTACH, ghats supports a range of spatial practices, some of which are 2009). She recently co-edited a volume spectacular such as aarti to Ganga and cremation rites. The on studies in heritage conservation and management- Cultural Landscapes and spectacles mesmerize but also evoke bhavs (feelings) creating Heritage Conservation in South Asia an aesthetic experience. (Routledge, 2017). [email protected] 36 TEKTON: Volume 4, Issue 2, September 2017 Landscape as a ‘Situated Event’ their cultural landscape should be interpreted The visually arresting unfolding panoramic as a situated event, of text enacted and views of the ghats seen from the river have performed, and experienced through all the dominated representations of Varanasi in senses.