Lord Shiva in Varanasi Visual Processes and the Representation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shaiva Symbols on Punch-Marked Coins

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH CULTURE SOCIETY ISSN: 2456-6683 Volume - 1, Issue - 7, Sept - 2017 Shaiva symbols on Punch-Marked Coins Dr.Kanhaiya Singh Post Doctoral Fellow, Ancient history, Archaeology and culture Department, Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Gorakhpur University Gorakhpur. UP, India Email - [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: The study of coins is called Numismatics. Although Coins are very small in size, but he is strongly present important historical sources . The earliest coins of India is known as Punch-marked coins (Aahat mudra). We have Found various type of symbol on Punch-marked coins (Aahat mudra) as sun, Wheel, Six armed Wheel, Meru, Swastik, Fish, Flower, Trident, Nandipada, Taurine, animals and Jyamitik etc. all symbols are meaning full and he present social, Economic, Political, Religious and cultural conditions of contemporary India. In this research paper is present the only Shaiva symbols on punch-marked coins and prove the religious believers of contemporary Indian society and culture. Key words: Coinage, Iconography, Symbols, Religion, Culture. 1. INTRODUCTION: Conis are most important sources for Indian historiography. Although he is very small in size, but its interruption can solved a large problem of ‘Dark age’ in ancient Indian history. The coins of most authentic pieces of evidence and enlighten us about various aspects of the human life and culture of the people. Though the history of the study of the ancient Indian coins goes to back to 1800 AD, when Coldwell Found some coins from Coimbatore. The earliest coins of ancient india is known as Punch-Marked coins (Aahat Mudra). Remarkable that the earliest coins of india is called Punch-Marked, nominated by James prinsep1 in 1835 A.D. -

Lions Clubs International

GN1067D Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing a Current Year Club Only - (President, Secretary or Treasure) District 321 E District Club Club Name Title (Missing) District 321 E 30064 BASTI Treasurer District 321 E 31511 DEORIA President District 321 E 31511 DEORIA Secretary District 321 E 31511 DEORIA Treasurer District 321 E 38880 GORAKHPUR VISHAL President District 321 E 38880 GORAKHPUR VISHAL Secretary District 321 E 38880 GORAKHPUR VISHAL Treasurer District 321 E 44316 BALLIA BHRIGU President District 321 E 44316 BALLIA BHRIGU Secretary District 321 E 44316 BALLIA BHRIGU Treasurer District 321 E 45215 JAUNPUR President District 321 E 45215 JAUNPUR Secretary District 321 E 45215 JAUNPUR Treasurer District 321 E 48896 GORAKHPUR GEETA President District 321 E 48896 GORAKHPUR GEETA Secretary District 321 E 48896 GORAKHPUR GEETA Treasurer District 321 E 51493 AURAI CENTRAL President District 321 E 51493 AURAI CENTRAL Secretary District 321 E 51493 AURAI CENTRAL Treasurer District 321 E 52495 VARANASI EAST President District 321 E 52495 VARANASI EAST Secretary District 321 E 52495 VARANASI EAST Treasurer District 321 E 56897 SHAKTINAGAR JWALAMUKHI President District 321 E 56897 SHAKTINAGAR JWALAMUKHI Secretary District 321 E 56897 SHAKTINAGAR JWALAMUKHI Treasurer District 321 E 57063 BHADOHI CITY President District 321 E 57063 BHADOHI CITY Secretary District 321 E 57063 BHADOHI CITY Treasurer District 321 E 58521 FAIZABAD AWADH President District 321 E 58521 FAIZABAD AWADH Secretary District 321 E 58521 FAIZABAD AWADH Treasurer District -

Profile, Pattern and Outcome of Shri Amaranth Ji Yatri Patients Attending Sher-I-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar, India During Holy Yatra of 2017

Open Access CRIMSON PUBLISHERS C Wings to the Research Biostatistics & Bioinformatics ISSN 2578-0247 Research Article Profile, Pattern and Outcome of Shri Amaranth Ji Yatri Patients attending Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar, India during Holy Yatra of 2017 G H Yatoo1, Mubashar Mashqoor Mir2 and Mohammad Sarwar Mir3* 1Department of Hospital Administration, SKIMS, India 2Department of Dermatology, GMC, India 3Department of Hospital Administration, SKIMS, India *Corresponding author: Mohammad Sarwar Mir, Senior Resident, Department of Hospital Administration, SKIMS, Srinagar, India Submission: May 09, 2018; Published: May 16, 2018 Abstract Introduction: Located deep in the Himalayas, the cave of Amarnath is one of the holiest pilgrimage site for Hindus in general and Shiva followers which sometimes these prove fatal. in particular. It is regarded to be the abode of Lord Shiva. Because of high altitude, rough terrain, harsh weather, pilgrims are prone to many illnesses Objective: To study the profile, pattern and outcome, among Shri Amarnath Ji yatri patients attending SKIMS in year 2017. Methodology: A prospective study was carried out during the yatra period, all pilgrims of Shri Amarnath ji Yatra who were referred to SKIMS from July-August 2017 were studied and the patients were followed from admission till discharge. The profile, pattern and outcome of illness in Yatris attendingResults: Yatra in the year 2017 was compared with the results of year 2011 and 2015. Out of 97 patients received at SKIMS, 54(55.67%) were having minor ailments and were seen on OPD basis, 43(44.32%) were admitted. 32(74.41%) admitted were males at the time of arrival 14(32.5%) were Road traffic Accidents followed by 7 patients (16.27%) who were Acute Myocardial Infarction. -

Paper Code: Dttm C205 Tourism in West Bengal Semester

HAND OUT FOR UGC NSQF SPONSORED ONE YEAR DILPOMA IN TRAVEL & TORUISM MANAGEMENT PAPER CODE: DTTM C205 TOURISM IN WEST BENGAL SEMESTER: SECOND PREPARED BY MD ABU BARKAT ALI UNIT-I: 1.TOURISM IN WEST BENGAL: AN OVERVIEW Evolution of Tourism Department The Department of Tourism was set up in 1959. The attention to the development of tourist facilities was given from the 3 Plan Period onwards, Early in 1950 the executive part of tourism organization came into being with the appointment of a Tourist Development Officer. He was assisted by some of the existing staff of Home (Transport) Department. In 1960-61 the Assistant Secretary of the Home (Transport) Department was made Director of Tourism ex-officio and a few posts of assistants were created. Subsequently, the Secretary of Home (Transport) Department became the ex-officio Director of Tourism. Two Regional Tourist Offices - one for the five North Bengal districts i.e., Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri, Cooch Behar, West Dinajpur and Maida with headquarters at Darjeeling and the other for the remaining districts of the State with headquarters at Kolkata were also set up. The Regional Office at KolKata started functioning on 2nd September, 1961. The Regional Office in Darjeeling was started on 1st May, 1962 by taking over the existing Tourist Bureau of the Govt. of India at Darjeeling. The tourism wing of the Home (Transport) Department was transferred to the Development Department on 1st September, 1962. Development. Commissioner then became the ex-officio Director of Tourism. Subsequently, in view of the increasing activities of tourism organization it was transformed into a full-fledged Tourism Department, though the Secretary of the Forest Department functioned as the Secretary, Tourism Department. -

Guide to 275 SIVA STHALAMS Glorified by Thevaram Hymns (Pathigams) of Nayanmars

Guide to 275 SIVA STHALAMS Glorified by Thevaram Hymns (Pathigams) of Nayanmars -****- by Tamarapu Sampath Kumaran About the Author: Mr T Sampath Kumaran is a freelance writer. He regularly contributes articles on Management, Business, Ancient Temples and Temple Architecture to many leading Dailies and Magazines. His articles for the young is very popular in “The Young World section” of THE HINDU. He was associated in the production of two Documentary films on Nava Tirupathi Temples, and Tirukkurungudi Temple in Tamilnadu. His book on “The Path of Ramanuja”, and “The Guide to 108 Divya Desams” in book form on the CD, has been well received in the religious circle. Preface: Tirth Yatras or pilgrimages have been an integral part of Hinduism. Pilgrimages are considered quite important by the ritualistic followers of Sanathana dharma. There are a few centers of sacredness, which are held at high esteem by the ardent devotees who dream to travel and worship God in these holy places. All these holy sites have some mythological significance attached to them. When people go to a temple, they say they go for Darsan – of the image of the presiding deity. The pinnacle act of Hindu worship is to stand in the presence of the deity and to look upon the image so as to see and be seen by the deity and to gain the blessings. There are thousands of Siva sthalams- pilgrimage sites - renowned for their divine images. And it is for the Darsan of these divine images as well the pilgrimage places themselves - which are believed to be the natural places where Gods have dwelled - the pilgrimage is made. -

Registration Form

REGISTRATION FORM Title: Prof./Dr./Mr./Ms. ……………. Name:………………………………………. Designation:…………………..Organization/Institution:……………………………………… Address:………………………………………………………………………..………………… City :…………………………… Postal code:…………………… Country:…………………... E-mail …………………………….. Mobile ………………………….. Tel …………………… Name of accompanying person(s) (if any) :………………………………………………. For foreign delegates only Nationality…………… Passport No.: ………………Date and Place of issue …………… Registration fee The registration fee includes conference kit, access to inaugural function, scientific sessions, exhibitions, lunch, dinner and session tea. Category Upto Aug 31, 2010 After Aug 31, 2010 On Spot Student* Rs. 1000 Rs. 1250 Rs. 1500 Faculty member Rs. 1500 Rs. 1750 Rs. 2000 Accompanying person** Rs. 750 Rs. 1000 Rs. 1250 Foreign delegate USD 100 USD 125 USD 150 *Endorsement by the supervisor, **Excludes registration kit. Mode of Presentation (Indicate preference) Symposium Presentation by Young Scientists: Oral /Poster (Size: 1mx1m) Broad Area:………………. Sub Area:……….. Title of presentation:……. Signature Date : Place: ACCOMMODATION FORM Limited accommodation is available on first come first serve basis to early registered participants in the guest house (Rs.400/- per night). Hotel accommodation is also available and may be booked directly or through travel agents (Email:[email protected]). As November is the festival season, the city is full of tourists. It will be difficult to arrange accommodation without advance payment and for those registered late. Name………………..…………………………………………. -

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 As of June, 2009

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 as of June, 2009 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male TOTAL District 321 E 25961 ALLAHABAD 10 11 9 16 25 District 321 E 25962 ALLAHABAD GREATER 8 4 8 20 28 District 321 E 26002 MIRZAPUR 19 22 19 57 76 District 321 E 26013 RENUKOOT 1 1 1 167 168 District 321 E 26021 VARANASI 4 4 4 56 60 District 321 E 30064 BASTI 0 0 0 21 21 District 321 E 30994 VARANASI VISHAL 18 18 18 28 46 District 321 E 31402 RENUSAGAR 3 2 2 62 64 District 321 E 31514 ROBERTSGANJ 0 0 0 25 25 District 321 E 35103 VARANASI GANGA 0 0 1 59 60 District 321 E 36259 ALLAHABAD CENTRAL 2 6 10 14 24 District 321 E 38098 VARANASI VARUNA 0 0 0 33 33 District 321 E 38880 GORAKHPUR VISHAL 2 2 3 16 19 District 321 E 40468 GORAKHPUR RAPTI 0 0 0 21 21 District 321 E 43275 ROBERTSGANJ KAIMOORE 12 0 1 15 16 District 321 E 45215 JAUNPUR 3 0 0 58 58 District 321 E 45467 VARANASI SHIVA 0 0 1 18 19 District 321 E 45953 SULTANPUR CENTRAL 0 0 0 27 27 District 321 E 46981 BHADOHI VARUNA 1 1 20 30 50 District 321 E 48896 GORAKHPUR GEETA 0 0 0 13 13 District 321 E 49039 ALLAHABAD CITY 32 57 110 227 337 District 321 E 49383 ALLAHABAD ADARSH 18 18 18 23 41 District 321 E 49956 ALLAHABAD EVES 0 0 34 1 35 District 321 E 49998 VARANASI SURYA 0 0 1 19 20 District 321 E 51013 ALLAHABAD CANTT 7 9 11 23 34 District 321 E 51494 VARANASI CITY 0 0 0 34 34 District 321 E 51583 JAUNPUR GOMTI 0 0 0 40 40 District 321 E 51689 MORWA 0 0 0 31 31 District 321 E 54995 VARANASI RUDRA 9 0 0 16 16 District -

MM XXVI No. 1.Pmd

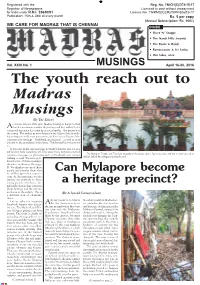

Registered with the Reg. No. TN/CH(C)/374/15-17 Registrar of Newspapers Licenced to post without prepayment for India under R.N.I. 53640/91 Licence No. TN/PMG(CCR)/WPP-506/15-17 Publication: 15th & 28th of every month Rs. 5 per copy (Annual Subscription: Rs. 100/-) WE CARE FOR MADRAS THAT IS CHENNAI INSIDE • Short ‘N’ Snappy • The Nandi Hills Swamiji • The Ryans & Rajaji • Rameswaram & Sri Lanka • Our lakes, once Vol. XXVI No. 1 MUSINGS April 16-30, 2016 The youth reach out to Madras Musings (By The Editor) s it steps into its 26th year, Madras Musings is happy to find Athat the maximum number of greetings and best wishes for its continued existence has come in on social media – the preserve of the young. This makes us most happy for we believe that by mak- ing an impact on the next generation, we have carried forward the concerns over heritage – both built and natural – as well as over our city to the guardians of the future. This by itself is a victory for us. It was only in the last issue that we made it known that we as a publication have completed 25. Ever since then, we have received countless messages on platforms such as Facebook and Twitter The Mylapore Temple and Tank look beautiful in the picture above. But come closer and this is what you will see wishing us well. We have pub- (below) behind the railings protecting the tank. lished some of these messages elsewhere in this issue (See page 3). -

Get Set Go Travels Hotel Akshaya Building, Opp: DRM Office, Waltair Station Approach Road, Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh 530016

Get Set Go Travels Hotel Akshaya Building, Opp: DRM Office, Waltair Station Approach Road, Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh 530016. Phone: +91 92468 14399, +91 90004 18895 Mail: [email protected] Web: www.getsetgotravels.in The Pancharama Kshetras or the (Pancharamas) are five ancient Hindu temples of Lord Shiva situated in Andhra Pradesh. These Sivalingas are formed out of one single Sivalinga. As per the legend, this five Sivalingas were one which was owned by the Rakshasa King Tarakasura. None could win over him due to the power of this Sivalinga. In a war between deities and Tarakasura, Kumara Swamy and Tarakasura were face to face. Kumara Swamy used his Sakthi aayudha to kíll Taraka. By the power of Sakti aayudha the body of Taraka was torn into pieces. But to the astonishment of Lord Kumara Swamy all the pieces reunited to give rise to Taraka. Kumara Swamy repeatedly broke the body into pieces and it was re-unified again and again. This confused Lord Kumara Swamy and was in an embarrassed state then Lord Sriman-Narayana appeared before him and said “Kumara! Don’t get depressed, without breaking the Shiva lingham worn by the asura you can’t kíll him” you should first break the Shiva lingam into pieces, then only you can kíll Taraka Lord Vishnu also said that after breaking, the shiva lingha it will try to unite. To prevent the Linga from uniting, all the pieces should be fixed in the place where they are fallen by worshiping them and erecting temples on them. By taking the word of Lord Vishnu, Lord Kumara Swamy used his Aagneasthra (weapon of fire) to break the Shiva lingha worn by Taraka, Once the Shiva lingha broke into five pieces and was trying to unite by making Omkara nada (Chanting Om). -

Within Hinduism's Vast Collection of Mythology, the Landscape of India

History, Heritage, and Myth Item Type Article Authors Simmons, Caleb Citation History, Heritage, and Myth Simmons, Caleb, Worldviews: Global Religions, Culture, and Ecology, 22, 216-237 (2018), DOI:https:// doi.org/10.1163/15685357-02203101 DOI 10.1163/15685357-02203101 Publisher BRILL ACADEMIC PUBLISHERS Journal WORLDVIEWS-GLOBAL RELIGIONS CULTURE AND ECOLOGY Rights Copyright © 2018, Brill. Download date 30/09/2021 20:27:09 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final accepted manuscript Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/631038 1 History, Heritage, and Myth: Local Historical Imagination in the Fight to Preserve Chamundi Hill in Mysore City1 Abstract: This essay examines popular and public discourse surrounding the broad, amorphous, and largely grassroots campaign to "Save Chamundi Hill" in Mysore City. The focus of this study is in the develop of the language of "heritage" relating to the Hill starting in the mid-2000s that implicitly connected its heritage to the mythic events of the slaying of the buffalo-demon. This essay argues that the connection between the Hill and "heritage" grows from an assumption that the landscape is historically important because of its role in the myth of the goddess and the buffalo- demon, which is interwoven into the city's history. It demonstrates that this assumption is rooted within a local historical consciousness that places mythic events within the chronology of human history that arose as a negotiation of Indian and colonial understandings of historiography. Keywords: Hinduism; Goddess; India; Myth; History; Mysore; Chamundi Hills; Heritage 1. Introduction The landscape of India plays a crucial role for religious life in the subcontinent as its topography plays an integral part in the collective mythic imagination with cities, villages, mountains, rivers, and regions serving as the stage upon which mythic events of the epics and Purāṇas unfolded. -

Bread Review 2007-08.Cdr

earc es h, E R d ic u s c a a t B i o n A B R E A D n d y t D e e i v c e o l S o t p m n e BREAD REVIEW 2007-08 BASIC RESEARCH, EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT (BREAD) SOCIETY earc es h, E R d ic u s c a a t B i o n A B R E A D n d y t D e e i v c BREAD REVIEW 2007-08 e o l S o t p m n e FROM THE SECRETARY'S DESK Dear Sir / Madam, BREAD Society's mission is to provide financial assistance to bright indigent students to pursue higher education till they attain their maximum potential while simultaneously inculcating good values among them. It also administers the donors' funds efficiently passing on every rupee of the donation to the scholar. BREAD Society has adopted its present methodology to identify the bright underprivileged students in 2003-04. Our experience over the past five years has made us refine our systems to ensure that we reach out to the most deserving students even in the most remote areas of the state. Our latest initiative in this regard is to try to get the BREAD Poster displayed in the Notice Boards of all the 1450 government and government aided institutions of higher education in Andhra Pradesh by mailing A-4 size colour posters to all the Principals. The abundant human resource wealth lying dormant, mostly in the remote rural areas of the countryside, can be unearthed to create a real knowledge based society at a nominal cost. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita