Maxchevy V 5.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 FOX NASCAR PRODUCTION STAFF 2 DAYTONA 500 PRODUCTION ELEMENTS 3-4 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE FACTS 5-6 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE HISTORY 7-8 DAYTONA SPEEDWEEKS ON FOX PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE 9-12 JEFF GORDON’S DAYTONA 500 KICKOFF CELEBRATION ON FOX 13 FOX DEPORTES 14 FOX DIGITAL 15-17 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 18 FOX NASCAR HISTORY & TIMELINE 19-21 MOTOR SPORTS ON FOX 22-24 BROADCASTER & EXECUTIVE BIOS 25-48 MEDIA INFORMATION The FOX NASCAR Daytona 500 press kit has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of this year’s “Great American Race” on Sunday, Feb. 21 (1:00 PM ET) on FOX and will be updated continuously on our press site: www.foxsports.com/presspass. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information and facilitate interview requests. Updated FOX NASCAR photography, featuring new FOX NASCAR analyst and four-time NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon, along with other FOX on-air personalities, can be downloaded via the aforementioned FOX Sports press pass website. If you need assistance with photography, contact Ileana Peña at 212/556-2588 or [email protected]. The 59th running of the Daytona 500 and all ancillary programming leading up to the race is available digitally via the FOX Sports GO app and online at www.FOXSportsGO.com. FOX SPORTS ON-SITE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Chris Hannan EVP, Communications & Cell: 310/871-6324; Integration [email protected] Lou D’Ermilio SVP, Media Relations Cell: 917/601-6898; [email protected] Erik Arneson VP, Media Relations Cell: 704/458-7926; [email protected] Megan Englehart Publicist, Media Relations Cell: 336/425-4762 [email protected] Eddie Motl Manager, Media Relations Cell: 845/313-5802 [email protected] Claudia Martinez Director, FOX Deportes Media Cell: 818/421-2994; Relations claudia.martinez@foxcom 2016 DAYTONA 500 MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL & REPLAY FOX Sports is conducting a media event and simultaneous conference call from the Daytona International Speedway Infield Media Center on Thursday, Feb. -

50 Years of NASCAR Captures All That Has Made Bill France’S Dream Into a Firm, Big-Money Reality

< mill NASCAR OF NASCAR ■ TP'S FAST, ITS FURIOUS, IT'S SPINE- I tingling, jump-out-of-youn-seat action, a sport created by a fan for the fans, it’s all part of the American dream. Conceived in a hotel room in Daytona, Florida, in 1948, NASCAR is now America’s fastest-growing sport and is fast becoming one of America’s most-watched sports. As crowds flock to see state-of-the-art, 700-horsepower cars powering their way around high-banked ovals, outmaneuvering, outpacing and outthinking each other, NASCAR has passed the half-century mark. 50 Years of NASCAR captures all that has made Bill France’s dream into a firm, big-money reality. It traces the history and the development of the sport through the faces behind the scene who have made the sport such a success and the personalities behind the helmets—the stars that the crowds flock to see. There is also a comprehensive statistics section featuring the results of the Winston Cup series and the all-time leaders in NASCAR’S driving history plus a chronology capturing the highlights of the sport. Packed throughout with dramatic color illustrations, each page is an action-packed celebration of all that has made the sport what it is today. Whether you are a die-hard fan or just an armchair follower of the sport, 50 Years of NASCAR is a must-have addition to the bookshelf of anyone with an interest in the sport. $29.95 USA/ $44.95 CAN THIS IS A CARLTON BOOK ISBN 1 85868 874 4 Copyright © Carlton Books Limited 1998 Project Editor: Chris Hawkes First published 1998 Project Art Editor: Zoe Maggs Reprinted with corrections 1999, 2000 Picture Research: Catherine Costelloe 10 9876 5 4321 Production: Sarah Corteel Design: Graham Curd, Steve Wilson All rights reserved. -

Holiday Catalog 2011 – 2012 Coo R L Pe D U V S D S

Holiday Catalog 2011 – 2012 Coo r l pe D u V S D s ! S EE PAGE 7 Reading for Racers Hot New Titles B Most Popular This Year RAANDND NEEWW ffrromom C oasoastalal 118181 MILLER’S TIME WAward Winner! THE HOME OF HEROES A Lifetime At Speed Fifty Years of Racing at Utica-Rome Speedway by Don Miller with Jim Donnelly by Bones Bourcier Close confidant of Roger Penske, co-founder A high-profile NASCAR asphalt oval before becoming of Penske Racing South, mentor of Rusty one of the region’s premier dirt tracks, Utica-Rome has Wallace and Ryan Newman, Bonneville welcomed over time just about every significant racer in Flats record-maker, technical innovator, the East. Beautiful ly written and heavily illustrated, this drag racer extraordinaire–Don Miller has seen and done it all. Limited Edition is a collector’s item! Hard cover, 304 pp, 200 B&W photos. S-1000 Price: $29.95 Available from Coastal 181 only from Oct. 1, 2011 through April 15, 2012 . Hard cover, 400 pp, 500 B&W JOHN FORCE and color photos. S-1167 Price: $55.00 The Straight Story of Drag Racing’s 300-mph Superstar STILL WIDE OPEN by Erik Arneson Second Edition Newly Revised Photo biography that covers Force's rise by Brad Doty and Dave Argabright from a penniless racer to leader of a multi- “Enhanced and Expanded,” this edition contains th e entire text team effort that includes his high-profile of the original 1999 release, PLUS two new chapters that bring daughter Ashley (2004 Driver of the Year and Rookie of the you up-to-date with Brad. -

A Lifetime's Collection of Hot Rods and Parts Heads to Auction in Florida

A lifetime’s collection of hot rods and parts heads to auction in Florida Kurt Ernst | Jan 15th, 2015 at 8am Fords stacked up in a Florida warehouse, awaiting the Koepke collection sale. Photos courtesy Yvette VanDerBrink. When Bob Koepke died in November of 2014, no one, not even his son, David, knew the secrets hidden in the brush of his overgrown Florida property. For nearly 50 years, the elder Koepke had collected parts and bodies from 1930s Fords and 1950s Chevrolets, along with aftermarket Components needed to make his own cars go faster. Now in the process of being sorted and cataloged, Bob Koepke’s impressive ColleCtion of Cars, bodies and parts will head to auCtion on April 11. Born in Gary, Indiana, in May of 1943, Bob grew up tending to Chores on the family’s farm. His first car was an old Ford Model A, purChased from older brother Karl for the prinCely sum (to a high sChool student in the early 1960s, anyway) of $25. Though other Cars would Come into his life, Bob never lost his passion for the Model A; it was, after all, the Car that introduCed him to the world of hot rodding. Determined to give his son a better life, Bob’s father insisted that he attend College. After graduating from Indiana University with a degree in aCCounting, Bob headed south to Florida’s SpaCe Coast, new wife in tow, to take an aCCounting job in the aerospaCe industry. Working for solid employers like Boeing and NASA, his Career took off, and for a while the family prospered under the hot Florida sun. -

Bunkie Knudsen and Smokey Yunick

Bunkie In sales and racing alike, Pontiac once was monster. Those were the wide-track years, the 1960s, and Pontiac’s most off-the-wall emporium was down in swampy Florida – Daytona Beach’s notorious, go-go-go, “Best Damn Garage in Town.” The Best Damn Garage in Town was Smokey Yunick’s private boozing club, automotive laboratory, and general lair of lair of black magic. It also was the birthplace of whatever on a given day Smokey was naming his step-down Hudson Hornets, turbo-fire V8 Chevrolets, Ford rooster-backs. Smokey certified them standard Detroit iron, the National Association of Stock Car Auto Racing declared them “Not in the spirit of the rules,” and most of the BDGT’s infuriated competition slandered them as downright cheaters rigged with sneaky fuel cavities, fraudulent dimensions, and dirty-trick engines. Hands-down within the NASCAR milieu, Smokey Yunick was the internal-combustion high priest, mad scientist, pirate outsider, whiskey mechanic and chief agitator devoted to the overthrow of all confining rules. NASCAR racing was young, the majority of Motor City manufacturers still were getting the hang of the race-of- Sunday-sell-on-Monday mantra, and Smokey – jumping ship and switching factories at every opportunity – knew how to play the factory game. By the time the hammer hit on that dreadful 1957 day, Smokey already was flying his third or fourth manufacture’s flag of convenience. And that truly was one dreadful 24 hours, June 6, 1957. Posterity named it the day of the Automobile Manufacturers Association ban, and it forced General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler - the Big Three - to roll up and quit subsidizing their complicated networks of covert NASCAR teams. -

Going National While Staying Southern: Stock Car Racing in America, 1949-1979

GOING NATIONAL WHILE STAYING SOUTHERN: STOCK CAR RACING IN AMERICA, 1949-1979 A Dissertation Presented to The Academic Faculty By Ben A. Shackleford In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the History and Sociology of Science and Technology Georgia Institute of Technology December, 2004 GOING NATIONAL WHILE STAYING SOUTHERN: STOCK CAR RACING IN AMERICA, 1949-1979 Approved By Dr. Steven Usselman Dr. Gus Giebelhause Dr. Doug Flamming Dr. Philip Scranton Dr. William Winders Date Approved 22 July 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A work of this scope inevitably draws upon resources outside the individual author. Luckily I have been able to draw upon many interested and willing librarians and archivists while conducting research for this project. I would like to thank Rebecca Lynch, Roger White, Maggie Dennis, Joyce Bedi, at the Smithsonian Institution. Buz McKim at the ISC archives, Betty Carlan at the International Motorsports Hall of Fame, the Staff of the National Automotive History Collection at the Detroit Public Library, and Bonnie Walworth at the Ford Motor Company archives in Dearborn, Michigan. I would also like to thank the Lemelson Center, the Atlanta History Center, the Riddle Foundation and the School of History, Technology and Society at Georgia Tech whose generosity permitted me to work in such a variety of collections. Studying the history of technology often requires technical expertise beyond that available in the classroom. During my experience as a racing mechanic and fabricator I was fortunate to have many very capable teachers who willingly shared their expertise. Among these are my Robert Wagner, Smokey Yunick, Chris Brown, Amos Johnson, Thomas Blam and Franz Blam. -

Robert L. Hoekstra

Curriculum Vitae Robert L. Hoekstra Department of Industrial Engineering and Management Systems College of Engineering University of Central Florida Orlando, FL 32816 (407) 823-6175 [email protected] I Background Education Ph.D. College of Engineering, University of Cincinnati, 1992 Dissertation: Design for Assembly M.Des. Master of Design, School of Design, Art, Architecture, and Planning, University of Cincinnati, 1988 A.B. General, Major: English, Calvin College, 1969 Employment History Academic Positions University of Central Florida 2014 – Present Associate Professor, School of Visual Arts and Design Teaching, research and service 1998 - Present Associate Professor, Industrial Engineering & Management Systems Teaching, research and service as detailed below 1995- 2010 Laboratory Director, Engine Research Laboratory Designed the facility, directed equipment installation, manage operating budget and direct laboratory personnel 1993 - 1997 Assistant Professor, Industrial Engineering & Management Systems Teaching, research and service as detailed below 1993 - 1994 Program Director, Transportation Systems, Florida Solar Energy Center Prepared research grant proposals, directed research initiatives, prepared reports and managed the fiscal operation of the program 1 University of Cincinnati 1988 - 1993 Assistant Director, Center for Robotics Research Prepared research grant proposals, directed research and prepared reports 1989 - 1993 Research Associate, Material Handling Research Center, Institute for Advanced Manufacturing Science -

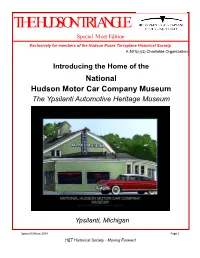

THE HUDSON TRIANGLE Special Meet Edition

THE HUDSON TRIANGLE Special Meet Edition Exclusively for members of the Hudson Essex Terraplane Historical Society. A 501(c)(3) Charitable Organization Introducing the Home of the National Hudson Motor Car Company Museum The Ypsilanti Automotive Heritage Museum Ypsilanti, Michigan Special Edition 2014 Page 1 HET Historical Society - Moving Forward The purpose of HETHS is: to discover the history of the Hudson Motor Car Company (HMCC); to locate products, writings, newspapers, journals, technical data, photographs, and objects that relate to HMCC history; to establish a HMCC museum and library; to promote the education of the public on the HMCC history. Filling a need for those who have an interest in preserving HET history, heritage, and the automobiles produced and sold by the Hudson Motor Car Company since its inception in 1909, is an active goal of the HETHS. Working closely with the HET Club, the HETHS regularly promotes Hudson related displays at various museums across the country. All donations are tax-deductible and further the Society goals. HETHS is eligible to receive tax-deductible donations of money, cars, literature, memorabilia and artwork. You are invited to join us in the pursuit of history. Dedicated to Preserving the History of Hudson Motor Cars HETHS © 2014 Page 2 Special Edition 2014 HET Historical Society - Moving Forward Departments Behind the Wheel With Mike Behind the Wheel 3 President’s Note 6 Summer is here, the HET Club ___________ International Meet has arrived and life is good! History We often hear, “it has been a busy year.” So instead I HMCC 1909-1957 4 will tell you the directors, officers and support staff of Did You Know 7 the Hudson Essex Terraplane Historical Society have had a very productive year. -

Living Estate Auction of Mr. & Mrs. H. A. "Humpy" Wheeler Day 1

10/01/21 09:12:22 Living Estate Auction of Mr. & Mrs. H. A. "Humpy" Wheeler Day 1 Auction Opens: Tue, Nov 6 8:00am ET Auction Closes: Tue, Nov 13 6:00pm ET Lot Title Lot Title 0001 1953 Hudson Hornet Coupe, Completely 0032 Framed quote by Humpy Wheeler concerning restored in 2014 as “Doc Hudson― from the Movie the visit of President Gerald Ford to his office Series “Cars.― in 1988. 0002 Legend's Race Car. 0033 Framed photograph of Humpy Wheeler and 0007 "Sully's Ghost" Guide Boat by Henry Gov. Jim Hunt. McCarthy. 0034 "Operation Commando Strike, photograph with 0009 Folbot Canoe. signatures of the participants at the Charlotte Motor Speedway. 0012 2006, Endurance Magazine Time Trial Series, Charlotte Motor Speedway. Giro Bicycle 0035 August, 2006, Gaston Gazette, "Hall of Fame" Helmet presented to Humpy Wheeler news article. 0013 Shimano, Trek, DCLV Carbon, Racing Bicycle 0036 1995, State of North Carolina, H.A. Wheeler, Frame. North Carolina Sports Development Commission. 0014 Men's, Schwinn, 26 inch Antique Bicycle. 0038 1998, Past and Present NASCAR print by D. 0015 Brick from the Indianapolis Speedway. McCrary, 0020 Dodge, Shelby, Pro Series, Framed Poster. 0039 Yogi Berra, framed photograph. 0021 Mark Martin, "The Eagle Flies", by Gary Hill, 0040 "Stroker Ace", framed movie poster. 1999. 0041 North Carolina Michael Easley photograph, 0022 1997, Sam Bass poster, "New Breed of Speed", personalized to Humpy Wheeler. Charlotte Motor Speedway. 0042 Autographed Brooks and Dunn, Kellogg's Corn 0023 Sam Bass, "Unbeatable", Lowes Motor Flakes box. Speedway. 0043 Sam Bass, "Blaze of Glory", 1996, Dale 0024 Sam Bass, "Assembly Line to Finish Line Team Earnhardt, Artist Proof Print. -

Hudson Seven Decades Ago, During The

Hudson Seven decades ago, during the pioneer years of stock car racing, nothing could stop the fabulous Hudson Hornets and their fabulous racing drivers. Dick Rathmann for instance, “ the braver Rathmann,” of the Rathmann brothers, himself and Jim, was one of the fastest Hudson drivers, as well as the toughest: should his Hornet need fresh tires and a tank of gasoline, he stop randomly in somebody else’s Hornet pit stall and threaten its mechanics with a pounding unless they serviced him; strategy always worked. But Rathmann was in a jam on a 1951 afternoon in California for a 250-lap race on the Oakland dirt track. Only one week earlier he’d been racing in the deep south where’d blown up his Hornet. A fresh one was available in Chicago, but only if Rathmann re-built it, because it had been in a rollover. So, after first making the long drive to Chicago, Rathmann was forced to spend three sleepless nights repairing the replacement Hornet and then had had to set out towing to Oakland in a blizzard. One hundred miles from Oakland, Rathmann’s tow car expired. Unwilling to miss the race, he hastily roped the dead tow car to the back of the Hornet, and arrived in Oakland so late that qualifying laps already had begun. And Rathmann scarcely had time to buckle on his helmet when his gas tank broke off. Which might have been a problem to somebody else, but not Rathmann: he simply approached the driver of another Hornet, told him he was taking his gas tank, and did. -

One of the Most Interesting Cars on Display in the Indianapolis Motor Speedway's Hall of Fame Museum Never Ran a Race

story by MARK DILL illustrations by TOM OSBORNE One of the most interesting cars on display in the Indianapolis Motor Speedway's Hall of Fame Museum never ran a race. Still, its peculiar and even frighteningly dangerous • looking design draws attention. Called "the sidecar," one look at it and you'll know how it got the nickname. The unique appearance of the racer centers on its cockpit, clearly reminiscent of a motorcycle sidecar. The idea was to place the driver to the left of the main body to give him better visibility and improve weight distribution on Indy's left turns. A rear engine design in an era when most Indy cars were still front engine roadsters, it looks like a pod strapped to the side of a missile. One shudders to think of the consequences of hitting the Speedway's concrete wall at over 150 mph. Officially the Hurst Floor Shifter Special, it was an entry for the 1964 Indianapolis 500 but was wrecked in time trials by NASCAR veteran Bobby Johns. This innovative machine was the brainstorm of one of the most colorful characters of post World War II American auto racing, Henry "Smokey" Yunick. Sporting Yunick's trademark black and gold colors, the Hurst car is a symbol of a creative mind unafraid to push the envelope in the quest for a speed advantage. And this creative mind had been pondering engines and mechanical desiQn since decades earlier. Born well North of the Mason-Dixon in Pennsylvania back in 1923, 12-year-old Henry Yunick cobbled together a tractor from junk car parts to help his family run their farm. -

Leadership Styles of Head NASCAR Executives: a Historical Perspective

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2020 Leadership Styles of Head NASCAR Executives: A Historical Perspective Joseph A. Hurd East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, Leadership Studies Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hurd, Joseph A., "Leadership Styles of Head NASCAR Executives: A Historical Perspective" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3705. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3705 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Leadership Styles of Head NASCAR Executives: A Historical Perspective _____________________________________ A dissertation presented to The faculty of the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership ______________________________________ by Joseph Aaron Hurd May 2020 ____________________________________ Dr. Don Good, Chair Dr. Bill Flora Dr. Virginia Foley Dr. Tom Lee Keywords: NASCAR, Autocratic Leadership, Bill France, Brian France, Jim France ABSTRACT Leadership Styles of Head NASCAR Executives: A Historical Perspective by Joseph Aaron Hurd This study sought to explore the leadership styles and theories employed throughout the existence of the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR). The research examines the decision process and subsequent outcomes, exploring how they ultimately affected the business and trajectory of the sport.