Hudson Seven Decades Ago, During The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sept 18—Craig Harmon “The History of Rambler And

Sept 18—Craig Harmon “The History of Rambler and September 25th, 2012 American Motors” LAST WEEK: Sept 25—Pat Crosby “The History of Jackson Rotary Last meeting: Our guests included: Natalie Krska (Court reporter for Calaveras county), a guest of and the Personal History of Pat Crosby” Irene Perbal-Boylson, and Shawna Molina introduced by Eddie Methered. Oct 2—Club Assembly – Membership John Swift gave us some of the new procedures for the Bowl-A-Thon this year. It will occur earlier in Oct 20—BOWLATHON the day – 2:00 PM for registration with bowling to start at 3:00PM. It should all be over before dark. Nov 13—Sergeant John Silva “Office of Emergency The Club will provide the BBQ’d food (I’m not sure the timing of that), and we really need sponsors to Services Project Lifesaver” make the event work fiscally. John provided information sheets on the levels of sponsorship and Nov 20—Beth Barnard on Volcano Theatre what’s offered for /$100, $200 & $300 sponsors. The Club will soon be painting Jackson’s fire hydrants white – I gather the participants know when. Irene Perbal-Boylson urges us all to bring visitors to the Club meeting. She suggests that former members may just be waiting for an invitation to re-join. In any case – bring a guest, and let her know when you’ve earned points. Tuesday 7:15am Plymouth: 49er RV Resort Frank Halvorson brought us up-to-date on happenings at the Hotel Leger in Moke Hill. A popular TV Wednesday 12:00 show undertakes to re-vamp decrepit hotels in a blitz fashion and then air the results. -

General Assembly of North Carolina Session 2005 Ratified Bill

GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA SESSION 2005 RATIFIED BILL RESOLUTION 2005-12 HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 375 A JOINT RESOLUTION HONORING NORTH CAROLINA'S GREAT NASCAR LEGENDS RALPH DALE EARNHARDT, SR., RALPH LEE EARNHARDT, LEE PETTY, ADAM KYLER PETTY, JULIUS TIMOTHY "TIM" FLOCK AND HIS COMPANION JOCKO FLOCKO, EDWIN KEITH "BANJO" MATTHEWS, CURTIS MORTON TURNER, EDWARD GLENN "FIREBALL" ROBERTS, ELZIE WYLIE "BUCK" BAKER, SR., AND AFRICAN-AMERICAN RACING PIONEER WENDELL OLIVER SCOTT, AND ENCOURAGING NASCAR TO SELECT NORTH CAROLINA AS THE LOCATION FOR ITS HALL OF FAME. Whereas, North Carolina takes great pride in its position as the stock car racing capital in the United States and the world and is the "Hub of Motorsports in the United States"; and Whereas, motorsports events have become and remain hugely popular with the people of North Carolina, with more than one million fans attending motorsports events in the State each year, thereby substantially enhancing the tourism industry in North Carolina; and Whereas, after World War II, stock car racing evolved in the foothills, the pinewoods, and the Piedmont, quickly becoming one of the deepest traditions in North Carolina popular culture; and Whereas, North Carolina's motorsports industry has an annual economic impact of $5.1 billion and creates an excess of 24,000 jobs with an average income of over $69,000; and Whereas, North Carolina is in the running to be the site of the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) Hall of Fame; and Whereas, 82% of the Nextel Cup Series, 72% -

Busch's Battle Ends in Glory

8 – THE DERRICK. / The News-Herald Wednesday, December 09, 2015 QUESTIONS & ATTITUDE Compelling questions... and maybe a few actual answers What will I do for NASCAR news? It’s as close as we get to NASCAR hanging a “Gone fishing” sign on the door. Now what? After 36 races, a goodbye to Jeff Gordon and con- SPEED FREAKS gratulations to Kyle Busch, and with only about A couple questions Mission accomplished two months until the engines crank at Daytona, we had to ask — you need more right now? These days, this is the ourselves closest thing NASCAR has to a dark season. But there’ll be news. What sort of news? Danica Patrick’s NASCAR’s corner-office suits are huddling with newest Busch’s battle the boys in legal to find a feasible way to turn its race teams into something resembling fran- GODSPEAK: Third chises, which would break from the independent- crew chief in contractor system that served the purposes four years. Crew since the late-’40s. Well, it served NASCAR’s ends in glory purposes, along with owners and drivers who chief No. 1, Tony Gibson, took ran fast enough to escape creditors. But times Kurt Busch to the have changed; you’ll soon be reading a lot about men named Rob Kauffman and Brent Dewar and Chase this year. something called the Race Team Alliance. KEN’S CALL: It’s starting to take on Will it affect the race fans and the the feel of a dial- racing? a-date, isn’t it? Nope. So maybe you shouldn’t pay attention. -

1953 Hudson Cars Described

1953 HUDSON CARS DESCRIBED 1953 HUDSON - GENERAL: A downsized Hudson arrived this year, called the Hudson Jet. It had styling that would be mimicked by the rest of the line in 1954. Gone was the Pacemaker. with its nameplate replaced by a new, lower level Wasp. The upper level Wasp, called the "Super Wasp," and it moved into the former Commodore 6 slot that now disappeared. The Hornet finally supplanted the Commodore 8 completely. The nameplate was retired, putting the 8-cylinder powerplant out to pasture. That L-head I-8, having served twenty long years from 1932 until 1952, was gone. The consolidation of lines and the removal of the Commodore Six and Eight allowed for less tooling in the Wasp-Hornet lines and should have saved money. The problem was that production kept dropping even though the cars were considered popular. The issue at hand was dated styling and the lack of an OHV V-8. At the root of the lower production was Hudson's lack of investment dollars when that trend to V8s and more modern styling was pulling the Big Three away from all other competition. Worse, a good deal the sales problems were the result of Hudson misreading their audience and thinking that these changes weren't needed. Even with the introduction of the Jet, production dropped. And Hudson's racing victories, that outshone all rivals, while earning respect for the brand, did not entice buyers into the showrooms. INNOVATIONS: The Hudson Jet, a smaller, more economical model, was introduced. It was an attempt to drop into the lower price market to pick up sales. -

NASCAR for Dummies (ISBN

spine=.672” Sports/Motor Sports ™ Making Everything Easier! 3rd Edition Now updated! Your authoritative guide to NASCAR — 3rd Edition on and off the track Open the book and find: ® Want to have the supreme NASCAR experience? Whether • Top driver Mark Martin’s personal NASCAR you’re new to this exciting sport or a longtime fan, this insights into the sport insider’s guide covers everything you want to know in • The lowdown on each NASCAR detail — from the anatomy of a stock car to the strategies track used by top drivers in the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series. • Why drivers are true athletes NASCAR • What’s new with NASCAR? — get the latest on the new racing rules, teams, drivers, car designs, and safety requirements • Explanations of NASCAR lingo • A crash course in stock-car racing — meet the teams and • How to win a race (it’s more than sponsors, understand the different NASCAR series, and find out just driving fast!) how drivers get started in the racing business • What happens during a pit stop • Take a test drive — explore a stock car inside and out, learn the • How to fit in with a NASCAR crowd rules of the track, and work with the race team • Understand the driver’s world — get inside a driver’s head and • Ten can’t-miss races of the year ® see what happens before, during, and after a race • NASCAR statistics, race car • Keep track of NASCAR events — from the stands or the comfort numbers, and milestones of home, follow the sport and get the most out of each race Go to dummies.com® for more! Learn to: • Identify the teams, drivers, and cars • Follow all the latest rules and regulations • Understand the top driver skills and racing strategies • Have the ultimate fan experience, at home or at the track Mark Martin burst onto the NASCAR scene in 1981 $21.99 US / $25.99 CN / £14.99 UK after earning four American Speed Association championships, and has been winning races and ISBN 978-0-470-43068-2 setting records ever since. -

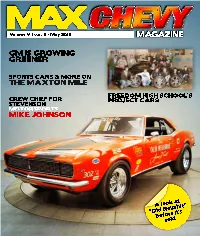

Maxchevy V 5.Pdf

Volume V, Issue 5 - May 2010 GM IS GROWING GREENER SPORTS CARS & MORE ON THE MAXTON MILE FREEDOM HIGH SCHOOL’S CREW CHIEF FOR PROJECT CARS STEVENSON MOTORSPORTS MIKE JOHNSON t look a A able” d Reli “Ol it’s before sold Volume V, Issue 5 May 17, 2010 “I think these guys deserve some recognition…” (Part I) It was around July of 1995. Over the many years of our friendship, it was always obvious what the conversation would be about when I called him, whether the call was about getting some otherwise-unavailable information or simply to visit. Both were always enjoyable. But when he called me, anything was fair game…and it often turned out that way. When he called this time, as usual, he came right to the point. “I been thinkin’, Jim. We’re right on top of celebrating the 40th anniversary of the small-block Chevy and there are still some of the original engineers out that ought to finally get some recognition for what they did. The PRI Show is comin’ up and I’ve told Steve Lewis (Show owner and producer) it’s time to put these guys on stage in front of the industry.” From this single conversation, Smokey Yunick made another indelible mark in his long string of historical contributions to the high performance and motorsports communities. Mind you, nothing was said about “Is this a good idea?” or “Do you think anybody cares about these people?” It was already a done deal. The only question up for discussion centered on the best way to accomplish the task. -

AM Spirit the Newsletter of the Northern Ramblers Car Club Canada’S National AMC Enthusiast Group Since 1979 in Our Forty-First Year

AM Spirit The Newsletter of the Northern Ramblers Car Club Canada’s National AMC Enthusiast Group Since 1979 In Our Forty-First Year September / October 2020 AM Spirit is the official publication of the Northern Ramblers Car Club Inc., promoting the “spirit” of the American Motors Corporation family of cars from 1902 - 1988. It is published six times a year. Deadlines for submissions for the newsletter are the 28th January, March, May, July, September & November. Allow seven days delivery for submissions sent by Canada Post’s regular service. Non profit #: 1335833 ISSN #: 1481-8086 Dues: $35.00 per year, for Canadian residents, US$40.00 for US residents. US$50.00 Int’l. Advertising rates: $100.00 per year for 6 business card size ads and membership. Larger ads, please call for rates. PRESIDENT Our Club exchanges newsletters and/or infor- mation with the following: Alfred Holden 190 St. George St., Apt. 801, AMC Rambler Club of Australia Toronto, ON. M5R 2N4 www.australian.amcrc.com/ 416 925 8073; cell 647 636-9323 [email protected]. American Motors Club of Alberta SECRETARY www.amcalberta.ca Phillip Simms, 189 Lyndhurst Drive, AMC Rambler Club Thornhill, ON L3T 6T5 Amcrc.com 905-709-1156 [email protected] Manitoba AMC Club www.amcman.com TREASURER & MEMBERSHIP AMC RELATED WEB SITES Roman Bratasiuk 12 Tremont Road Javelin Home Page Etobicoke, ON M9B 3X5 [email protected] www.javelinamx.com 416-231-8362 AMO National EDITOR, ARCHIVIST www.amonational.com Ron Morrison 176 Sheardown Drive The Coupe Coop Nobleton, ON L0G 1N0 www.matadorcoupe.com -

Buick Club of America Volume XXXVI No

1968 Buick Electra 225 owned by Steve Dodson Monthly Newsletter of the St Louis Chapter Buick Club of America Volume XXXVI No. 7 July 2017 Hi All … I hope everyone is having a great summer so far. I am always frank and honest…and this month’s director’s letter is an urgent call for our club to step up and help. Guys and gals… we are in desperate need to sell our trophy classes for the Shriners Benefit Car Show. We are less than 3 months away and have sold only 15 of our 32 classes. Richard Self has volunteered to revisit last GATEWAY GAZETTE 1 year’s contacts made by Doug Stahl, and Mark Kistner is following up on some leads. If we cannot sell these classes, we will not be able to pay for trophies this year. We really need everyone to step up to make this come together. Doug Stahl went to businesses that he frequented regularly… is there a business you visit that may want to contribute? Are your co-workers generous? Maybe have people poll $5.00 each together to sponsor a class. If everyone just asks a few businesses… we will be able to make this come together in time for the show. I have sold three classes and have been busy working on attendance prizes and raffle baskets. On my annual car trip I received verbal confirmation from Mothers and Laid Back for items again this year. I will also be visiting FastLane Cars and EPC Computers next week. September will be here before we know it. -

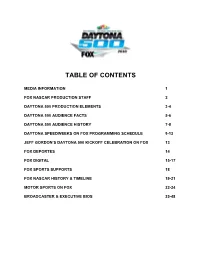

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 FOX NASCAR PRODUCTION STAFF 2 DAYTONA 500 PRODUCTION ELEMENTS 3-4 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE FACTS 5-6 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE HISTORY 7-8 DAYTONA SPEEDWEEKS ON FOX PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE 9-12 JEFF GORDON’S DAYTONA 500 KICKOFF CELEBRATION ON FOX 13 FOX DEPORTES 14 FOX DIGITAL 15-17 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 18 FOX NASCAR HISTORY & TIMELINE 19-21 MOTOR SPORTS ON FOX 22-24 BROADCASTER & EXECUTIVE BIOS 25-48 MEDIA INFORMATION The FOX NASCAR Daytona 500 press kit has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of this year’s “Great American Race” on Sunday, Feb. 21 (1:00 PM ET) on FOX and will be updated continuously on our press site: www.foxsports.com/presspass. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information and facilitate interview requests. Updated FOX NASCAR photography, featuring new FOX NASCAR analyst and four-time NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon, along with other FOX on-air personalities, can be downloaded via the aforementioned FOX Sports press pass website. If you need assistance with photography, contact Ileana Peña at 212/556-2588 or [email protected]. The 59th running of the Daytona 500 and all ancillary programming leading up to the race is available digitally via the FOX Sports GO app and online at www.FOXSportsGO.com. FOX SPORTS ON-SITE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Chris Hannan EVP, Communications & Cell: 310/871-6324; Integration [email protected] Lou D’Ermilio SVP, Media Relations Cell: 917/601-6898; [email protected] Erik Arneson VP, Media Relations Cell: 704/458-7926; [email protected] Megan Englehart Publicist, Media Relations Cell: 336/425-4762 [email protected] Eddie Motl Manager, Media Relations Cell: 845/313-5802 [email protected] Claudia Martinez Director, FOX Deportes Media Cell: 818/421-2994; Relations claudia.martinez@foxcom 2016 DAYTONA 500 MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL & REPLAY FOX Sports is conducting a media event and simultaneous conference call from the Daytona International Speedway Infield Media Center on Thursday, Feb. -

Nascar, Its Pioneer Racing Families and Drivers, and North Carolina Motor Racing

GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA SESSION 2003 RATIFIED BILL RESOLUTION 2003-11 HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 1161 A JOINT RESOLUTION HONORING NASCAR, ITS PIONEER RACING FAMILIES AND DRIVERS, AND NORTH CAROLINA MOTOR RACING. Whereas, North Carolina takes great pride in its position as the stock car racing capital of the United States and the world; and Whereas, North Carolina is the home of NASCAR, which staged its first sanctioned "purely stock car" race at the Charlotte Speedway on June 19, 1949; and Whereas, since that time, NASCAR and motorsports events have become and remain hugely popular with the people of North Carolina, with more than one million people attending motorsports events in North Carolina each year, thereby substantially enhancing the tourism industry in and economy of North Carolina; and Whereas, North Carolina currently hosts five NASCAR Winston Cup events, with two being held at the North Carolina Speedway in Rockingham and three at the Lowe's Motor Speedway, near Charlotte, and is thus the stock car racing capital of the world; and Whereas, these Winston Cup races materially affect North Carolina's economy, and the loss of any Winston Cup event would have a tremendous negative impact on jobs and tax revenues in the Rockingham and Charlotte areas and the tourism industry in North Carolina in general; and Whereas, North Carolina has established the William States Lee College of Engineering at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte which offers an undergraduate program concentrating on motorsports engineering; and -

Woods' Lakefront Park Assessed At

. i ~ ., fl More Than '.000 Families Read .The Grosse Pointe News ross~ ews Every Thursday flom. 0/ Ih. NeWI 99 Kercbeval TV. 2.&900 Complete News Coverage of All the Pointes 5c Per Cop~' Entered as Second Clasa Matter VOLUME I4-NO. 12 13.00 Per Yell. GROSSE POINTE, MICHIGAN, MARCH 19, 1953 at the Post Office at Detroit, Mteh. FuJly Paid Circulation Incineration HEAJ)LI~ES Architect's Drawing of Proposed Auditorium-Gymnasium Woods' Lakefront f)f the Called Best "T}:EK Park Assessed at After Survey' A$ Compiled by the GrO$U Pohzte N erN Engineers Make Exhaustive $95,650 for 1953 Study of All Methods of Thursda,Y, March 12 Solving Pointe Problem. EVEN THOUGH no diplomatic St. Clair Shores, in Which Recreation Site Is Located, break appears imminent. the Notifies City of New Assessment; Tax Bill Is $5,344.68 The Grosse Pointe-Harper United States weighed stiff new Woods Disposal Committee protests to Communist Czecho- slovakia, concerning the shooting The Iakefront park owned by the Woods and located will proceed with all possible down of an American F .84 Thun. within the City of St. Clair Shores, has been assessed at speed to establish an inciner';' derjet 15 miles inside American. $95,650, council members were informed at their regular alion plant to handle all the occupied Bavaria in Germany. meeting, Monday, March 16. ,~ refuse and garbage collected Shoot-back orders were issued to A letter to the Woods from d in the area, This decision has American pilots to counter any the st. Clair Shores tax assess- Spot Promote been reached after a thorough future hit-and-run attacks by ment office, notified officials that study was made to determine Red fighter planes in Europe. -

July 2020 Newsletter

Traveling with the Payson Arizona J U L Y 2 0 2 0 PRESIDENT Steve Fowler THE RIM COUNTRY CLASSIC AUTO CLUB IS A NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION FOR I hope this finds each of you well and THE PURPOSE OF: finding some joy in your life. The year is Providing social, educational half over, and it reminds me of the and recreational activities for its membership. saying about “half empty or half full”. Participating in and support- This has been a more empty year than ing civic activities for the most in many respects, but if we count betterment of the community. Encouraging and promoting our blessings, we may find that the year the preservation and restora- is more half full. So far as I know, the tion of classic motor vehicles. Providing organized activities members of the club have thus far involving the driving and dodged the bullet where the virus is showing of member’s cars. concerned. We’ve also not (so far) been burned out, and the fire gave a nice RCCAC meets at respite from the weekly traffic jam 6:30p.m. on the first coming from the valley. We have had Wednesday of the several very enjoyable club events while month normally at Tiny’s Restaurant, 600 still maintaining relatively healthy E. Hwy. 260 in Payson distances. We still don’t know whether See page #2 for meeting we will be able to have our car show, but [email protected] place during pandemic we have a possible contingency plan in [email protected] place that will at least let us have some fun.