Land Reform in South Africa: a Status Report 2008 Edward Lahiff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Implementation of Quotas: African Experiences Quota Report Series

The Implementation of Quotas: African Experiences Quota Report Series Edited by Julie Ballington In Collaboration with This report was compiled from the findings and case studies presented at an International IDEA, EISA and SADC Parliamentary Forum Workshop held on 11–12 November 2004, Pretoria, South Africa. © International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance 2004 This is an International IDEA publication. International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. Applications for permission to reproduce or translate all or any part of this publication should be made to: Information Unit International IDEA SE -103 34 Stockholm Sweden International IDEA encourages dissemination of its work and will promptly respond to requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publications. Graphic design by: Magnus Alkmar Cover photos: Anoli Perera, Sri Lanka Printed by: Trydells Tryckeri AB, Sweden ISBN: 91-85391-17-4 Preface The International Institute for Democracy and a global research project on the implementation and Electoral Assistance (IDEA), an intergovernmental use of quotas worldwide in cooperation with the organization with member states across all continents, Department of Political Science, Stockholm University. seeks to support sustainable democracy in both new By comparing the employment of gender quotas in dif- and long-established democracies. Drawing on com- ferent political contexts this project seeks to gauge parative analysis and experience, IDEA works to bolster whether, and under what conditions, quotas can be electoral processes, enhance political equality and par- implemented successfully. It also aims to raise general ticipation and develop democratic institutions and awareness of the use of gender quotas as an instrument practices. -

Complete Dissertation

VU Research Portal Private Wildlife Governance in a Context of Radical Uncertainty Kamuti, T. 2016 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Kamuti, T. (2016). Private Wildlife Governance in a Context of Radical Uncertainty: Dynamics of Game Farming Policy and Practice in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Vrije Universiteit. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT Private Wildlife Governance in a Context of Radical Uncertainty Dynamics of Game Farming Policy and Practice in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. V. Subramaniam, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de Faculteit der Sociale Wetenschappen op woensdag 22 juni 2016 om 13.45 uur in de aula van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door Tariro Kamuti geboren te Mt Darwin, Zimbabwe promotoren: prof.dr. -

Who Is Governing the ''New'' South Africa?

Who is Governing the ”New” South Africa? Marianne Séverin, Pierre Aycard To cite this version: Marianne Séverin, Pierre Aycard. Who is Governing the ”New” South Africa?: Elites, Networks and Governing Styles (1985-2003). IFAS Working Paper Series / Les Cahiers de l’ IFAS, 2006, 8, p. 13-37. hal-00799193 HAL Id: hal-00799193 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00799193 Submitted on 11 Mar 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Ten Years of Democratic South Africa transition Accomplished? by Aurelia WA KABWE-SEGATTI, Nicolas PEJOUT and Philippe GUILLAUME Les Nouveaux Cahiers de l’IFAS / IFAS Working Paper Series is a series of occasional working papers, dedicated to disseminating research in the social and human sciences on Southern Africa. Under the supervision of appointed editors, each issue covers a specifi c theme; papers originate from researchers, experts or post-graduate students from France, Europe or Southern Africa with an interest in the region. The views and opinions expressed here remain the sole responsibility of the authors. Any query regarding this publication should be directed to the chief editor. Chief editor: Aurelia WA KABWE – SEGATTI, IFAS-Research director. -

African National Congress NATIONAL to NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob

African National Congress NATIONAL TO NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob Gedleyihlekisa 2. MOTLANTHE Kgalema Petrus 3. MBETE Baleka 4. MANUEL Trevor Andrew 5. MANDELA Nomzamo Winfred 6. DLAMINI-ZUMA Nkosazana 7. RADEBE Jeffery Thamsanqa 8. SISULU Lindiwe Noceba 9. NZIMANDE Bonginkosi Emmanuel 10. PANDOR Grace Naledi Mandisa 11. MBALULA Fikile April 12. NQAKULA Nosiviwe Noluthando 13. SKWEYIYA Zola Sidney Themba 14. ROUTLEDGE Nozizwe Charlotte 15. MTHETHWA Nkosinathi 16. DLAMINI Bathabile Olive 17. JORDAN Zweledinga Pallo 18. MOTSHEKGA Matsie Angelina 19. GIGABA Knowledge Malusi Nkanyezi 20. HOGAN Barbara Anne 21. SHICEKA Sicelo 22. MFEKETO Nomaindiya Cathleen 23. MAKHENKESI Makhenkesi Arnold 24. TSHABALALA- MSIMANG Mantombazana Edmie 25. RAMATHLODI Ngoako Abel 26. MABUDAFHASI Thizwilondi Rejoyce 27. GODOGWANA Enoch 28. HENDRICKS Lindiwe 29. CHARLES Nqakula 30. SHABANGU Susan 31. SEXWALE Tokyo Mosima Gabriel 32. XINGWANA Lulama Marytheresa 33. NYANDA Siphiwe 34. SONJICA Buyelwa Patience 35. NDEBELE Joel Sibusiso 36. YENGENI Lumka Elizabeth 37. CRONIN Jeremy Patrick 38. NKOANA- MASHABANE Maite Emily 39. SISULU Max Vuyisile 40. VAN DER MERWE Susan Comber 41. HOLOMISA Sango Patekile 42. PETERS Elizabeth Dipuo 43. MOTSHEKGA Mathole Serofo 44. ZULU Lindiwe Daphne 45. CHABANE Ohm Collins 46. SIBIYA Noluthando Agatha 47. HANEKOM Derek Andre` 48. BOGOPANE-ZULU Hendrietta Ipeleng 49. MPAHLWA Mandisi Bongani Mabuto 50. TOBIAS Thandi Vivian 51. MOTSOALEDI Pakishe Aaron 52. MOLEWA Bomo Edana Edith 53. PHAAHLA Matume Joseph 54. PULE Dina Deliwe 55. MDLADLANA Membathisi Mphumzi Shepherd 56. DLULANE Beauty Nomvuzo 57. MANAMELA Kgwaridi Buti 58. MOLOI-MOROPA Joyce Clementine 59. EBRAHIM Ebrahim Ismail 60. MAHLANGU-NKABINDE Gwendoline Lindiwe 61. NJIKELANA Sisa James 62. HAJAIJ Fatima 63. -

1 Rural Governance in Post-1994 South Africa

Rural governance in post-1994 South Africa: Has the question of citizenship for rural inhabitants been settled 10 years in South Africa’s democracy? Lungisile Ntsebeza Associate Professor Department of Sociology University of Cape Town South Africa [email protected] ABSTRACT Against the background of rural local governance that was dominated by apartheid created authoritarian Tribal Authorities, the post-1994 South African state has committed itself to the establishment of an accountable, democratic and effective form of governance throughout the country, including rural areas falling under the jurisdiction of traditional authorities (chiefs of various ranks). However, I argue that the promulgation of the Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act and the Communal Land Rights Bill (CLRB) runs the risk of compromising this project. The Framework Act establishes traditional councils which are dominated by unelected traditional authorities and their appointees, while the CLRB gives these structures unprecedented powers over land administration and allocation. This raises, I argue, serious questions about the meaning of democracy and citizenship in post-1994, in particular for rural people. Rural citizens do not seem to enjoy the same rights as their urban counterparts who elect their leaders. 1 Introduction The post-1994 South African state has committed itself to the establishment of a democratic, representative and accountable form of governance throughout the country.1 This is by far a most challenging task especially -

South Africa South Africa at a Glance: 2007-08

Country Report South Africa South Africa at a glance: 2007-08 OVERVIEW The ruling African National Congress (ANC) is expected to maintain its overwhelming hegemony during the forecast period. However, the party and its leadership will be preoccupied with maintaining party unity and an orderly process of electing a successor to Thabo Mbeki as ANC president at the party!s national congress in December 2007. Assuming a sound mix of fiscal and monetary policy combined with public-sector wage moderation, weaker administered prices and lower private-sector unit labour costs (owing to productivity gains), inflation is expected to remain within the target range of 3-6% in 2007-08. Further growth in construction and continued expansion in total domestic demand is expected to support real GDP growth of 4.5% in 2007 and 5.1% in 2008. Fairly strong global demand and high commodity prices will help to boost exports, but rising imports mean that the current account is forecast to remain in deficit, although the deficit should narrow in 2007-08. Key changes from last month Political outlook • Political prospects remain unchanged from the previous month. Economic policy outlook • The South African Reserve Bank (SARB, the central bank) raised interest rates by a further 50 basis points in December, taking the benchmark repurchase (repo) rate to 9%. The SARB based its decision mainly on the risks posed by high rates of growth in household spending and consumer credit and by the threat to inflation posed by the depreciation in the exchange rate. Although the risk from international oil prices has abated, food price inflation is rising significantly and is likely to continue to do so in the coming months. -

Government Communication and Information System (GCIS) Is Primarily Responsible for Facilitating Communi- Cation Between Government and the People

04.Government 3/30/06 11:43 AM Page 29 Government The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa took effect in February 1997. The Constitution is the supreme law of the land. No other law or government action may supersede its provisions. South Africa’s Constitution is one of the most progressive in the world and has been acclaimed internationally. The Preamble to the Constitution states that its aims are to: • heal the divisions of the past and establish a society based on democratic values, social justice and funda- mental human rights • improve the quality of life of all citizens and free the potential of each person • lay the foundations for a democratic and open society in which government is based on the will of the people and every citizen is equally protected by law • build a united and democratic South Africa able to take its rightful place as a sovereign state in the family of nations. Government Government consists of national, provincial and local spheres. The powers of the legislature, executive and courts are separate. Parliament Parliament consists of the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces (NCOP). Parliamentary 29 04.Government 3/30/06 11:43 AM Page 30 Pocket Guide to South Africa 2005/06 sittings are open to the public. Several measures have been implemented to make Parliament more accessible and accountable. The National Assembly consists of no fewer than 350 and no more than 400 members elected through a system of proportional representation for a term of five years. It elects the President and scrutinises the executive. -

The Thinker Congratulates Dr Roots Everywhere

CONTENTS In This Issue 2 Letter from the Editor 6 Contributors to this Edition The Longest Revolution 10 Angie Motshekga Sex for sale: The State as Pimp – Decriminalising Prostitution 14 Zukiswa Mqolomba The Century of the Woman 18 Amanda Mbali Dlamini Celebrating Umkhonto we Sizwe On the Cover: 22 Ayanda Dlodlo The journey is long, but Why forsake Muslim women? there is no turning back... 26 Waheeda Amien © GreatStock / Masterfile The power of thinking women: Transformative action for a kinder 30 world Marthe Muller Young African Women who envision the African future 36 Siki Dlanga Entrepreneurship and innovation to address job creation 30 40 South African Breweries Promoting 21st century South African women from an economic 42 perspective Yazini April Investing in astronomy as a priority platform for research and 46 innovation Naledi Pandor Why is equality between women and men so important? 48 Lynn Carneson McGregor 40 Women in Engineering: What holds us back? 52 Mamosa Motjope South Africa’s women: The Untold Story 56 Jennifer Lindsey-Renton Making rights real for women: Changing conversations about 58 empowerment Ronel Rensburg and Estelle de Beer Adopt-a-River 46 62 Department of Water Affairs Community Health Workers: Changing roles, shifting thinking 64 Melanie Roberts and Nicola Stuart-Thompson South African Foreign Policy: A practitioner’s perspective 68 Petunia Mpoza Creative Lens 70 Poetry by Bridget Pitt Readers' Forum © SAWID, SAB, Department of 72 Woman of the 21st Century by Nozibele Qutu Science and Technology Volume 42 / 2012 1 LETTER FROM THE MaNagiNg EDiTOR am writing the editorial this month looks forward, with a deeply inspiring because we decided that this belief that future generations of black I issue would be written entirely South African women will continue to by women. -

Gendered Institutional Change in South Africa: the Case of the State Security Sector

Gendered Institutional Change in South Africa: The Case of the State Security Sector Lara Monica De Klerk PhD – The University of Edinburgh – 2011 Table of Contents Contents ................................................................................................................... i List of Tables and Figures ...................................................................................... v List of Abbreviations and Acronyms ..................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................ ix Abstract ................................................................................................................... xi Declaration .......................................................................................................... xiii CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION ................................................ 1 1.1 The Research Question in Broader Perspective ......................................... 4 1.1.1 Gender Gains: Descriptive and Substantive Representation of Women ............... 5 1.1.2 Timely Transitions: South Africa and the Global Feminist Movement ................. 8 1.1.3 Shift in Security Thinking: Placing People First ...................................................... 11 1.2 Structure of Thesis Text ............................................................................ 14 PART I CHAPTER TWO FEMINIST NEW INSTITUTIONALISM AND TRANSITIONAL STATES ......................................................19 -

Parliament Rsa Joint Committee on Ethics And

PARLIAMENT RSA JOINT COMMITTEE ON ETHICS AND MEMBERS' INTERESTS REGISTER OF MEMBERS' INTERESTS 2013 Abrahams, Beverley Lynnette ((DA-NCOP)) 1. SHARES AND OTHER FINANCIAL INTERESTS No Nature Nominal Value Name of Company 100 R1 000 Telkom 100 R2 000 Vodacom 2. REMUNERATED EMPLOYMENT OUTSIDE PARLIAMENT Nothing to disclose. 3. DIRECTORSHIP AND PARTNERSHIPS Directorship/Partnership Type of Business Klip Eldo's Arts Arts 4. CONSULTANCIES OR RETAINERSHIPS Nothing to disclose. 5. SPONSORSHIPS Nothing to disclose. 6. GIFTS AND HOSPITALITY Nothing to disclose. 7. BENEFITS Nothing to disclose. 8. TRAVEL Nothing to disclose. 9. LAND AND PROPERTY Description Location Extent House Eldorado Park Normal House Eldorado Park Normal 10. PENSIONS Nothing to disclose. Abram, Salamuddi (ANC) 1. SHARES AND OTHER FINANCIAL INTERESTS No Nature Nominal Value Name of Company 2 008 Ordinary Sanlam 1 300 " Old Mutual 20 PLC Investec Unit Trusts R47 255.08 Stanlib Unit Trusts R37 133.56 Nedbank Member Interest R36 898 Vrystaat Ko -operasie Shares R40 000 MTN Zakhele 11 Ordinary Investec 2. REMUNERATED EMPLOYMENT OUTSIDE PARLIAMENT Nothing to disclose. 3. DIRECTORSHIP AND PARTNERSHIPS Nothing to disclose. 4. CONSULTANCIES OR RETAINERSHIPS Nothing to disclose. 5. SPONSORSHIPS Nothing to disclose. 6. GIFTS AND HOSPITALITY Nothing to disclose. 7. BENEFITS Nothing to disclose. 8. TRAVEL Nothing to disclose. 9. LAND AND PROPERTY Description Location Extent Erf 7295 Benoni +-941sq.m . Ptn 4, East Anglia Frankfurt 192,7224ha Unit 5 Village View Magaliessig 179sq.m. Holding 121 RAH 50% Int. in CC Benoni +-1,6ha Stand 20/25 Sandton 542sq.m. Unit 21 Benoni 55sq.m. Erf 2409 Benoni 1 190sq.m. -

CONTENTS INHOUD and Weekly Index En Weekllkse Indeks Page Gazette Bladsy Koerant No

2 NO.301a3 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 24 AUGUST 2007 For purposes of reference, all Proclamations, Government Aile Proklamasies, Goewermentskennlsgewings, Aigemene Notices, General Notices and Board Notices published are Kennlsgewlngs en Raadskennisgewings gepubliseer, word vir included in the following table of contents which thus forms a verwysingsdoelelndes in die volgende Inhoudsopgawe inge weekly index. Let yourself be guided by the Gazette numbers in slult wat dus 'n weeklikse indeks voorstel. Laat uself deur die the righthand column: Koerantnommers in die regterhandse kolom lei: CONTENTS INHOUD and weekly Index en weekllkse Indeks Page Gazette Bladsy Koerant No. No. No. No. No. No. GOVERNMENT AND GENERAL NOTICES GOEWERMENTS· EN ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS Agriculture, Department of Arbeid, Departement van General Notices Goewermenffikenn~gewmg 1013 Fertilizer Farm Feeds. Agricultural R. 713 Wet op ArbeidsverhoUdinge (66/1995): Remedies and Slack Remedies Act Bedingingsraad vir die Wassery-, Droog (3611947): Extension of the definitiOn of skocnrnaak- en Kleurnywerheid (Natal): farm feed to include farm feeds prepared Uitbreiding van wysiging van Kollek1iewe for any person in accordance with the Ooreenkoms na Nie-partye . 13 30165 directions for his own use 66 30183 1016 Marketing of Agricultural Products Act Blnnelandse Sake, Departement van (47/1996): Invitation to comment on the Goewermentskennisgewings application received for the increase of statutory levies in the Wine Industry....... 68 30183 760 Births and Deaths Registration Act (51/1992): Alteration of forenames . 6 30183 Education, Department of 761 do.: do . 7 30183 Government Notice 762 do.: Alteration of surnames . 11 30163 763 do.: do .. 33 30183 709 Higher Education Act (101/1997): Investigation conducted at the University Aigemene Kennisgewing of limpopo: Report of the Independent 1008 Refugees Act (130/1998): Public Assessor 3 30169 announcement to asylum seekers in the General Notice refuge backlog project. -

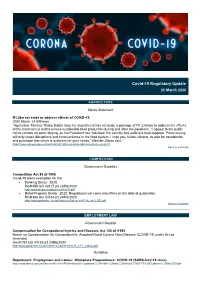

Covid-19 Regulatory Update 25Mar2020

Covid-19 Regulatory Update 25 March 2020 AGRICULTURE Media Statement R1.2bn set aside to address effects of COVID-19. 2020 March 24 SANews “Agriculture Minister Thoko Didiza says her department has set aside a package of R1.2 billion to address the effects of the Coronavirus and to ensure sustainable food production during and after the pandemic. “I appeal to the public not to embark on panic buying, as the President has indicated; the country has sufficient food supplies. Panic buying will only cause disruptions and inconvenience in the food system. I urge you, fellow-citizens, to also be considerate and purchase that which is sufficient for your needs,” Minister Didiza said.” https://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/r12bn-set-aside-address-effects-covid-19 Back to Contents COMPETITION Government Gazettes Competition Act 89 of 1998 Covid-19 block exemption for the: • Banking Sector, 2020. RGN355 GG 43127 p3 23Mar2020 http://www.dti.gov.za/gazzettes/43127.pdf • Retail Property Sector, 2020: Regulations will come into effect on the date of publication. RGN358 GG 43134 p3 24Mar2020 http://www.gpwonline.co.za/Gazettes/Gazettes/43134_24-3_DTI.pdf Back to Contents EMPLOYMENT LAW Government Gazette Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act 130 of /1993 Notice on Compensation for Occupationally- Acquired Novel Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19) under Act as amended. GenN193 GG 43126 p3 23Mar2020 http://www.gpwonline.co.za/Gazettes/Gazettes/43126_23-3_Labour.pdf Guideline Department: Employment and Labour. Workplace Preparedness: COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-19 virus). http://www.labour.gov.za/DocumentCenter/Publications/Occupational%20Health%20and%20Safety/COVID-19%20Guideline%20Mar2020.pdf Covid-19 Regulatory Update: 25 March 2020 Media Statement UIF, CF safety net intervention details.