UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Voices of Silence In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Following Is Most of the Text of the Presentation I Did at Readercon 29

The following is most of the text of the presentation I did at Readercon 29. I ran out of time, so I wasn't able to give the entire talk. And my Powerpoint file became corrupted, so I gave the presentation without the images, as I'd originally planned. Here, then, is the original, as requested by a couple of the folks who attended the presentation. THE HISTORY OF HORROR LITERATURE IN AFRICA IN THE 20TH CENTURY Horror literature has not been restricted to the United States, the United Kingdom, and Europe, despite what critics and historians of the genre assume. Most countries which have a flourishing market for popular literature have seen natively-written horror fiction, whether in the form of dime novels, short stories, or novels. This is true of the European countries, whose horror writers are given at least a cursory mention in the broader types of horror criticism. But this is also true of countries outside of Europe, and in countries and continents where Western horror critics dare not tread, like Africa. Now, a thorough history of African horror literature is beyond the time I have today, so what follows is going to be a more limited coverage, of African horror literature in the twentieth century. I’ll be going alphabetically and chronologically through three time periods: 1901-1940, 1941-1970, and 1971-2000. I’d love to be able to tell you a unified theory of African horror literature for those time periods, but there isn’t one. Africa is far too large for that. -

Women in the Middle East and North Africa: Issues for Congress

Women in the Middle East and North Africa: Issues for Congress June 19, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46423 SUMMARY R46423 Women in the Middle East and North Africa: June 19, 2020 Issues for Congress Zoe Danon The status of women in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) has garnered Section Research Manager widespread interest among many Members of Congress. Many experts have found that women in this region fare worse than those in other parts of the world on a range of Sarah R. Collins social, economic, legal and political measures. Some attribute this underperformance to Research Assistant gender roles and perspectives (including discriminatory laws and beliefs), and challenges facing the region overall (such as a preponderance of undemocratic governments, poor economic growth, civil wars, and mass displacement, which often disproportionately affect women). Some key issues facing many women in the region include the following: Unequal Legal Rights. Women in the MENA region face greater legal discrimination than women in any other region, with differential laws on issues such as marriage and divorce, freedom of movement, and inheritance, as well as limited to no legal protection from domestic violence. Constraints on Economic Participation and Opportunity. Regional conditions, in addition to gender-based discrimination, contribute to a significant difference between men and women’s participation in MENA economies. For example, women do not participate in the labor force to the same degree as women in other regions, and those who do participate face on average nearly twice the levels of unemployment than men. Underrepresentation in Political Processes. -

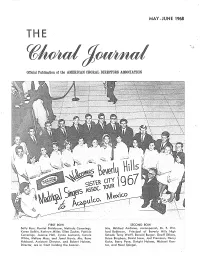

May -June 1968 T E

MAY -JUNE 1968 T E Official Publication of the AMERICAN CHORAL DIRECTORS ASSOCIATION FIRST ROW SECOND ROW Sally Ross, Harriet Steinbaum, Melinda Cummings, Mrs. Mildred Andrews; accompanist; Dr. F. Wil Karen Balkin, Kathryn Miller, Ellen Zucker, Patricia lard Robinson, Principal of Beverly Hills High Cummings, Joanne Hall, lynne Levinson, Carole School; Terry Wolff, Ronald Burger, Geoff Shlaes, White, Melissa Moss, and Janet Harris. Mrs. Rena Brian Bingham, David Loew; Joel Pressman, Henry Hubbard, Assistant Director, and Robert Holmes, Kahn, Barry Pyne, Dwight Holmes, Michael Kan Director, are in front holding the banner. tor, and Neal Spiegel. vent with numerical superiority and fi ic, festival, or meeting by which more d)1UUH tIt,e ------1 nancial strength to speak as the choral choral directors will become aware of voice of this country an'd still maintain the aims, purposes and value of ACDA. our 'dues at the present level of $6.00 a This issue carries the first Dues No Executive Secretary's year the need to double our membership tice for the 1968-69 fiscal year. Although this coming year was expressed by Pres July 1 is the first day of that year, many '--------:Jluk ident Decker and the National, Divisional of you win be away on vacation or at While it. fs impossible to report in de and ,State officers. A renewed plea was summer school and it is the hope of the tail on all meetings of the National issued that each ACDA member make it executive committee that you will help Board, the Executive Committee, the Di his personal obligation to bring in one both the organization and yourself by vision and state Chairmen and open new member this fall to swell the ranks paying your dues now before the end of sessions, several important plans and of ACDA to help us through this coming the current school year. -

The Integration of Women's Rights Into the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership

R6177 EMHRN Women's Report 14/05/2003 1:55 PM Page i The Integration of Women’s Rights into the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership Women’s Rights in Algeria, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, Syria and Tunisia by Rabéa Naciri and Isis Nusair Published by the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Network R6177 EMHRN Women's Report 14/05/2003 1:55 PM Page ii Copenhagen, May 2003 Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Network Wilders Plads 8H 1403 Copenhagen K Denmark Tel: + 45 32 69 89 10 Fax: +45 32 69 89 01 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.euromedrights.net © copyright 2003 Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Network Bibliographic information Title: Integrating Women’s Rights in the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership Personal Authors: Naciri, Rábea; Nusair, Isis Editors: Han, Sarah and Jorgensen, Marit Floe Corporate Author: Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Network Publisher: Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Network Date of Publication: 20030500 Pages: 76 ISBN: 87-91224-03-9 Original Language: French – L’intégration des droits des femmes dans le Partenariat euro- mediterranéen. Translation into English: Sharpe, Susan Translation into Arabic: Al-Haddad, Aiman H. Index terms: Women / Gender discrimination / Discrimination / Equality before the law / Violence against women /Family / Marriage/ Freedom of association / Freedom of movement / Political Participation / European Union Geographical terms: Mediterranean countries / North Africa / Middle East The report is published with the financial support of the EU Commission and the Heinrich Böll Foundation. The opinions expressed by the authors does not represent the official point of view neither of the EU Commission nor the Heinrich Böll Foundation. Cover design: Leila Drar Layout design: Genprint and 80:20 - Educating and Acting for a Better World, Ireland. -

"Aart" Zwemvereniging Meise Vlaams-Brabant Classic Swimming Meeting Aarschot (BEL) 21/04//22/04/2018 AART - Overzicht Op Namen

"aart" Zwemvereniging Meise Vlaams-Brabant Classic Swimming Meeting Aarschot (BEL) 21/04//22/04/2018 AART - Overzicht op namen Overzicht op namen Korte baan (25m) "Aart" Zwemvereniging Meise AART / PROVB / BEL 562 Borré Klara 04 : 3 200 vrije slag 2:39.31 S 1/10/2017 Landen (BEL) 9 400 wisselslag NT 16 400 vrije slag 5:52.08 L 5/11/2017 Sint-Pieters Woluwe (BEL) 19 100 vlinderslag 1:36.88 S 25/06/2017 Meise (BEL) 27 50 vrije slag 31.37 L 7/01/2018 Antwerpen (BEL) 34 100 rugslag 1:21.54 S 24/09/2017 Dilkom 1700 Dilbeek (BEL) 533 Borré Lauren 02 : 3 200 vrije slag 2:53.34 L 15/07/2017 ANTWERPEN (BEL) 9 400 wisselslag 7:09.87 S 16 400 vrije slag 6:07.94 S 12/03/2017 Sint-Pieters-Leeuw (BEL) 19 100 vlinderslag 1:29.79 L 15/07/2017 ANTWERPEN (BEL) 520 Christiaens Lander 04 : 4 200 vrije slag 2:42.70 S 26/11/2017 Strombeek Bever (BEL) 6 50 rugslag 38.52 S 11/11/2017 Liedekerke (BEL) 12 200 rugslag 2:55.64 S 18/02/2017 Leuven (BEL) 18 100 vlinderslag NT 25/06/2017 Meise (BEL) 28 400 wisselslag NT 32 100 wisselslag 1:30.81 S 519 Christiaens Senne 04 : 4 200 vrije slag 2:41.94 S 22/04/2017 Aarschot (BEL) 8 200 schoolslag 3:34.39 S 12 200 rugslag 3:00.37 S 26/11/2017 Strombeek Bever (BEL) 20 100 schoolslag 1:31.34 S 19/11/2017 Leuven (BEL) 28 400 wisselslag NT 32 100 wisselslag 1:24.68 S 23/04/2017 Aarschot (BEL) 585 De Keersmaeker Anthe 04 : 19 100 vlinderslag 1:30.40 S 25/06/2017 Meise (BEL) 23 100 vrije slag 1:07.85 S 11/11/2017 Liedekerke (BEL) 27 50 vrije slag 31.61 S 18/11/2017 NIJLEN (BEL) 31 100 wisselslag NT 623 De Munnynck Jarne 99 : 2 -

A Discursive Analysis of Women's Femininities Within the Context Of

A Discursive Analysis of Women’s Femininities within the Context of Tunisian Tourism A thesis submitted to Middlesex University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Heather Jeffrey Middlesex University Business School February 2017 Abstract Tourism has been hailed as a vehicle for gender equality and women’s empowerment and yet the relationship between these is far from simple. As tourism is created in already gendered societies, the ability of the industry to empower is shaped by existing gender norms and discourses. Therefore utilising a postcolonial feminist frame, the primary focus of this thesis is to critically explore both the discursive role of tourism and its influence in (re)constructing feminine identities in Tunisia. Informed by the works of Michel Foucault, and postcolonial feminism a critical discourse analysis is performed to identify discourses on femininity within the (re)presentations of Tunisian women in the Tunisian National Tourism Office’s brochures and website. Critical discourse analysis often risks disempowering the communities it seeks to analyse and as such fifteen semi-structured, in-depth interviews were carried out with Tunisian women involved in the Tunisian tourism industry. The interviews were shaped by a terrorist attack targeting tourists that had happened just two weeks before. Interestingly both the promotional materials and the interviews display two particular discourses on femininity, the modern and uncovered daughter of Bourguiba, and the southern covered Other. Of these discourses, it is the daughter of Bourguiba who is privileged and the southern veiled Other who is excluded. These discourses have been fomented since independence from France in 1956 and the rule of President Habib Bourguiba, but they still have a very material impact on the lives of Tunisian women today as evidenced in the interviews. -

Republic of Seychelles

REPUBLIC OF SEYCHELLES MINAMATA INITIAL ASSESSMENT REPORT 2016 Document title Minamata Initial Assessment Report 2016 Document short title MIA Report Date 15th Mar 2017 Consultants AAI Enterprise Pty Ltd Lead Consultant, Mr Cliff Gonzalves, and Inventory Team, Ms Janet Dewea, Mrs Shirley Mondon and Ms Elaine Mondon First draft contributions from Mr Dinesh Aggarwal. Second draft contributions from Dr David Evers, Dr David Buck, and Ms Amy Sauer. Acknowledgements We would like to thank everyone who participated in the development of this document, including experts at the UNDP. Cover page photos by Mr. Cliff Gonzalves and the late Mr. Terrence Lafortune. Disclaimer This document does not necessarily represent the official views of the Government of Seychelles, the United Nations Development Programme, the Global Environment Facility, or the Secretariat of the Minamata Convention on Mercury. 2 Table of Contents ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................. 7 Foreword (draft) .................................................................................................... 9 Executive Summary ................................................................................................. 10 I. Results of the national mercury Inventory .............................................................................................. 10 II. Policy, regulatory and institutional assessment ................................................................................... -

French (08/31/21)

Bulletin 2021-22 French (08/31/21) evolved over time by interpreting related forms of cultural French representation and expression in order to develop an informed critical perspective on a matter of current debate. Contact: Tili Boon Cuillé Prerequisite: In-Perspective course. Phone: 314-935-5175 • In-Depth Courses (L34 French 370s-390s) Email: [email protected] These courses build upon the strong foundation students Website: http://rll.wustl.edu have acquired in In-Perspective courses. Students have the opportunity to take the plunge and explore a topic in the Courses professor’s area of expertise, learning to situate the subject Visit online course listings to view semester offerings for in its historical and cultural context and to moderate their L34 French (https://courses.wustl.edu/CourseInfo.aspx? own views with respect to those of other cultural critics. sch=L&dept=L34&crslvl=1:4). Prerequisite: In-Perspective course. Undergraduate French courses include the following categories: L34 French 1011 Essential French I Workshop Application of the curriculum presented in French 101D. Pass/ • Cultural Expression (French 307D) Fail only. Grade dependent on attendance and participation. Limited to 12 students. Students must be enrolled concurrently in This course enables students to reinforce and refine French 101D. their French written and oral expression while exploring Credit 1 unit. EN: H culturally rich contexts and addressing socially relevant questions. Emphasis is placed on concrete and creative L34 French 101D French Level I: Essential French I description and narration. Prerequisite: L34 French 204 or This course immerses students in the French language and equivalent. Francophone culture from around the world, focusing on rapid acquisition of spoken and written French as well as listening Current topic: Les Banlieues. -

Vlaamse Rand VLAAMSE RAND DOORGELICHT

Asse Beersel Dilbeek Drogenbos Grimbergen Hoeilaart Kraainem Linkebeek Machelen Meise Merchtem Overijse Sint-Genesius-Rode Sint-Pieters-Leeuw Tervuren Vilvoorde Wemmel Wezembeek-Oppem Zaventem Vlaamse Rand VLAAMSE RAND DOORGELICHT Studiedienst van de Vlaamse Regering oktober 2011 Samenstelling Diensten voor het Algemeen Regeringsbeleid Studiedienst van de Vlaamse Regering Cijferboek: Naomi Plevoets Georneth Santos Tekst: Patrick De Klerck Met medewerking van het Documentatiecentrum Vlaamse Rand Verantwoordelijke uitgever Josée Lemaître Administrateur-generaal Boudewijnlaan 30 bus 23 1000 Brussel Depotnummer D/2011/3241/185 http://www.vlaanderen.be/svr INHOUD INLEIDING ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Algemene situering .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Demografie ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Aantal inwoners neemt toe ............................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Aantal huishoudens neemt toe....................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Bevolking is relatief jong én vergrijst verder -

Sixth Periodic Report Submitted by Seychelles Under Article 18 of the Convention, Due in 2017*

CEDAW/C/SYC/6 Distr.: General 22 June 2018 Original: English English, French and Spanish only ADVANCE UNEDITED VERSION Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women Sixth periodic report submitted by Seychelles under article 18 of the Convention, due in 2017* [Date received: 14 June 2018] * The present document is being issued without formal editing. CEDAW/C/SYC/6 Background information 1. The Seychelles is an archipelago of about 115 islands, divided into two main typographical groups: the Mahé group is mostly granitic islands of 43 islands, characterised by relatively high mountains rising out of the sea with very little coastal lands, whereas the coralline group of 73 islands are mostly flat, with few geographical inland features. The land mass is 453 km2, compared to more than 1.2 km2 of Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Mahé is the main island and lies between 4 degrees South latitude and 55 degrees east longitude. 2. Politically, the country is relatively stable with regular parliamentary and presidential elections held nearly every five years. In terms of history, Seychelles gained independence from Britain in 1976 and remains a member of the Commonwealth of Nations. In 1977, there was a coup d’état and a single party state was established in 1979. In 1992, a multiparty system took effect and a new constitution was adopted in 1993. 3. Ethnically, Seychelles is diverse due to the various ethnic origins of the population: Africa, Europe and Asia. The society is relatively harmonious in terms of race and there are intermarriages. The estimated population, according to Seychelles in Figures 2016 (National Bureau of Statistics, 2016) was 93, 400, with 46, 300 males and 47, 100 females. -

1 Institutional Changes in the Maghreb: Toward a Modern Gender

Institutional Changes in the Maghreb: Toward a Modern Gender Regime? Valentine M. Moghadam Professor of Sociology and International Affairs Northeastern University [email protected] DRAFT – December 2016 Abstract The countries of the Maghreb – Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia – are part of the Middle East and North Africa region, which is widely assumed to be resistant to women’s equality and empowerment. And yet, the region has experienced significant changes in women’s legal status, political participation, and social positions, along with continued contention over Muslim family law and women’s equal citizenship. Do the institutional and normative changes signal a shift in the “gender regime” from patriarchal to modern? To what extent have women’s rights organizations contributed to such changes? While mapping the changes that have occurred, and offering some comparisons to Egypt, another North African country that has seen fewer legal and normative changes in the direction of women’s equality, the paper identifies the persistent constraints that prevent both the empowerment of all women and broader socio-political transformation. The paper draws on the author’s research in and on the region since the early 1990s, analysis of patterns and trends since the Arab Spring of 2011, and the relevant secondary sources. Introduction The Middle East and North Africa region (MENA) is widely assumed to be resistant to women’s equality and empowerment. Many scholars have identified conservative social norms, patriarchal cultural practices, and the dominance of Islam as barriers to women’s empowerment and gender equality (Alexander and Welzel 2011; Ciftci 2010; Donno and Russett 2004; Fish 2002; Inglehart and Norris 2003; Rizzo et al 2007). -

French Department Faculty 33 - 35 French Department Awards 36 - 38 French House Fellows Program 39

Couverture: La Conciergerie et le Pont au Change, Paris TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Course Descriptions 2 - 26 French 350 27 French 360/370 28 - 29 Linguistics and Related Course Descriptions 30 French Advanced Placement Policies & Language Requirements 31 Requirements for the Major 31 The French Cultural Studies Major 31 Maison Française/French House 32 Wellesley-in-Aix 32 French Department Faculty 33 - 35 French Department Awards 36 - 38 French House Fellows Program 39 French Department extensions: Sarah Allahverdi (781) 283-2403 Hélène Bilis x2413 Venita Datta x2414 Sylvaine Egron-Sparrow x2415 Marie-Cecile Ganne-Schiermeier x2412 Scott Gunther x2444 Andrea Levitt x2410 Barry Lydgate, Chair x2404/x2439 Catherine Masson x2417 Codruta Morari x2479 Vicki Mistacco x2406 James Petterson x2423 Anjali Prabhu x2495 Marie-Paule Tranvouez x2975 French House assistantes x2413 Faculty on leave during 2012-2013: Scott Gunther (Spring) Andrea Levitt (Spring) Catherine Masson Vicki Mistacco (Fall) James Petterson (Spring) Please visit us at: http://web.wellesley.edu/web/Acad/French http://www.wellesley.edu/OIS/Aix/index.html http://www.facebook.com/pages/Wellesley-College-French- Department/112088402145775 1 FRENCH 101-102 (Fall & Spring) Beginning French I and II Systematic training in all the language skills, with special emphasis on communication, self- expression and cultural insight. A multimedia course based on the video series French in Action. Classes are supplemented by regular assignments in a variety of video, audio, print and Web-based materials to give students practice using authentic French accurately and expressively. Three class periods a week. Each semester earns 1.0 unit of credit; however, both semesters must be completed satisfactorily to receive credit for either course.