Fusing the Voices: the Appropriation and Distillation of the Waste Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Waste Land: a Personal Grouse

The Waste Land: A Personal Grouse Leon Surette University of Western Ontario Eliot¶s Waste Land must be the most discussed and analyzed poem of its length in the language, yet, for all that, it is perhaps still the most contested of all poems firmly ensconced in the canon. Initially receivedat least by its boostersas an articulation of the alienation, disillusion and scepticism of the young twentieth century, it has since been attacked from many anglesas reactionary, mystical, homosexual, anti-Semitic, elitist, phallocentric andperhaps most damaginglyas a con. The last criticism comes from the rather acid pen of Lawrence Rainey, who denounces the whole of Modernist art DV OLWWOH PRUH WKDQ ³D VWUDWHJ\ ZKHUHE\ WKH ZRUN of art invites and solicits its cRPPRGLILFDWLRQ´ (3).1 The Waste Land, Rainey says, was ³DQ HIIRUW WR DIILUP the output of a specific marketing-publicity apparatus through the enactment of a triumphal and triumphant occasion´ 7KHUHLVQRGRXEWWKDWWKHSXEOLFDWLRQRIThe Waste Land was orchestrated by Eliot, Pound, and Eliot¶s Harvard friend, Schofield Thayer, co-editor of The Dial, but if we are to condemn all artworks whose creators indulged in self promotion, the canon would shrink radically. Of course, the poem has its defendersindeed, they are legion; however, few any longer defend the poem¶V ³P\WKLFDO PHWKRG´DIHature emphasized by early boosters and by Eliot himself. 5RQDOG %XVK IRU H[DPSOH GLVPLVVHV WKH ³)UD]HU DQG :HVWRQ LPDJHU\´DV³VXSHULPSRVHGSLHFHPHDORQWRVHFWLRQVWKDWKDGEHHQ ZULWWHQHDUOLHU´an assessment with which it is difficult to disagree. +RZHYHUKHJRHVRQWRVXUPLVH³WKDW(OLRWKDGVRPHNLQGRIVKRUW- lived religious illumination during the process of re-envisioning the IUDJPHQWVRIKLVSRHP´ WKHUHE\SURVSHFWLYHO\GHIHQGLQJLWIURP Rainey¶s accusations of manipulative career buildingwhich it certainly was. -

Poetics and the Waste Land

Poetics and The Waste Land Subjects, Objects and the “Poem Including History” Wassim Rustom A Thesis Presented to The Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages University of Oslo In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the MA Degree May 2016 Poetics and The Waste Land Subjects, Objects and the “Poem Including History” Wassim Rustom © Wassim Rustom 2016 Poetics and The Waste Land: Subjects, Objects and the “Poem Including History” Wassim Rustom http://www.duo.uio.no Abstract The aim of this thesis is to trace key elements of the poetics that produced The Waste Land, T. S. Eliot’s landmark work of modernist poetry. Part I of the thesis examines the development of the Hulme-Pound-Eliot strand of modernist poetry through a focus on the question of subjectivity and the relationship between philosophical-epistemological ideas and modernist poetics. It traces a movement from a poetic approach centred on the individual consciousness towards one that aims to incorporate multiple subjectivities. Part II offers a complementary account of Eliot’s shift towards a more expansive scope of subject matter and of the fragmented poetic structure of The Waste Land. The argument is based on Jacques Rancière’s analysis of the modern regime of poetics dominant in the West since the Romantics, which identifies “literature” with the “life of a people” and is characterized by an inclusive logic that poeticizes ordinary subjects, objects and fragments. To my parents Contents Introduction.........................................................................................................................1 Part I 1 Early Modernism and Turn-of-the-century Philosophy: Subjectivity and Objectivity...9 1.1 Subjectivity and Narrative Technique................................................................................ -

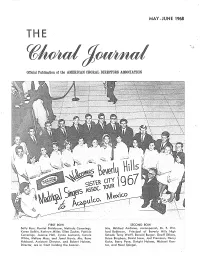

May -June 1968 T E

MAY -JUNE 1968 T E Official Publication of the AMERICAN CHORAL DIRECTORS ASSOCIATION FIRST ROW SECOND ROW Sally Ross, Harriet Steinbaum, Melinda Cummings, Mrs. Mildred Andrews; accompanist; Dr. F. Wil Karen Balkin, Kathryn Miller, Ellen Zucker, Patricia lard Robinson, Principal of Beverly Hills High Cummings, Joanne Hall, lynne Levinson, Carole School; Terry Wolff, Ronald Burger, Geoff Shlaes, White, Melissa Moss, and Janet Harris. Mrs. Rena Brian Bingham, David Loew; Joel Pressman, Henry Hubbard, Assistant Director, and Robert Holmes, Kahn, Barry Pyne, Dwight Holmes, Michael Kan Director, are in front holding the banner. tor, and Neal Spiegel. vent with numerical superiority and fi ic, festival, or meeting by which more d)1UUH tIt,e ------1 nancial strength to speak as the choral choral directors will become aware of voice of this country an'd still maintain the aims, purposes and value of ACDA. our 'dues at the present level of $6.00 a This issue carries the first Dues No Executive Secretary's year the need to double our membership tice for the 1968-69 fiscal year. Although this coming year was expressed by Pres July 1 is the first day of that year, many '--------:Jluk ident Decker and the National, Divisional of you win be away on vacation or at While it. fs impossible to report in de and ,State officers. A renewed plea was summer school and it is the hope of the tail on all meetings of the National issued that each ACDA member make it executive committee that you will help Board, the Executive Committee, the Di his personal obligation to bring in one both the organization and yourself by vision and state Chairmen and open new member this fall to swell the ranks paying your dues now before the end of sessions, several important plans and of ACDA to help us through this coming the current school year. -

The Waste Land by T

The Waste Land by T. S. Eliot Copyright Notice ©1998−2002; ©2002 by Gale. Gale is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Gale and Design® and Thomson Learning are trademarks used herein under license. ©2007 eNotes.com LLC ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. For complete copyright information on these eNotes please visit: http://www.enotes.com/waste−land/copyright Table of Contents 1. The Waste Land: Introduction 2. Text of the Poem 3. T. S. Eliot Biography 4. Summary 5. Themes 6. Style 7. Historical Context 8. Critical Overview 9. Essays and Criticism 10. Topics for Further Study 11. Media Adaptations 12. What Do I Read Next? 13. Bibliography and Further Reading 14. Copyright Introduction Because of his wide−ranging contributions to poetry, criticism, prose, and drama, some critics consider Thomas Sterns Eliot one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century. The Waste Land can arguably be cited as his most influential work. When Eliot published this complex poem in 1922—first in his own literary magazine Criterion, then a month later in wider circulation in the Dial— it set off a critical firestorm in the literary world. The work is commonly regarded as one of the seminal works of modernist literature. Indeed, when many critics saw the poem for the first time, it seemed too modern. -

Cultural & Heritagetourism

Cultural & HeritageTourism a Handbook for Community Champions A publication of: The Federal-Provincial-Territorial Ministers’ Table on Culture and Heritage (FPT) Table of Contents The views presented here reflect the Acknowledgements 2 Section B – Planning for Cultural/Heritage Tourism 32 opinions of the authors, and do not How to Use this Handbook 3 5. Plan for a Community-Based Cultural/Heritage Tourism Destination ������������������������������������������������ 32 necessarily represent the official posi- 5�1 Understand the Planning Process ������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 32 tion of the Provinces and Territories Developed for Community “Champions” ��������������������������������������� 3 which supported the project: Handbook Organization ����������������������������������������������������� 3 5�2 Get Ready for Visitors ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 33 Showcase Studies ���������������������������������������������������������� 4 Alberta Showcase: Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump and the Fort Museum of the NWMP Develop Aboriginal Partnerships ��� 34 Learn More… �������������������������������������������������������������� 4 5�3 Assess Your Potential (Baseline Surveys and Inventory) ������������������������������������������������������������� 37 6. Prepare Your People �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 41 Section A – Why Cultural/Heritage Tourism is Important 5 6�1 Welcome -

Journal of the American Theatre Organ Society

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN THEATRE ORGAN SOCIETY '_ --~~~ - -- - ·- - -- ~--'- -'. Orbil ID™eeclronic 1yn~e1izer P,UJ ~ -~eo~re01pinel organ equo1... ~e newe;I woy lo mo <emu1ic rromWur ilzec Now with the Orbit III electronic synthesizer from slowly, just as the theatre organist did by opening and Wurlitzer you can create new synthesized sounds in closing the chamber louvers. stantly ... in performance. And with the built-in Orbit III synthesizer, this This new Wurlitzer instrument is also a theatre organ, instrument can play exciting combinations of synthe with a sectionalized vibrato/tremolo, toy counter, in sized, new sounds, along with traditional organ music. A dependent tibias on each keyboard and the penetrating built-in cassette player/recorder lets you play along with kinura voice that all combine to recreate the sounds of pre-recorded tapes for even more dimensions in sound. the twenty-ton Mighty Wurlitzers of silent screen days. But you've got to play the Orbit III to believe it. And it's a cathedral/classical organ, too, with its own in Stop in at your Wurlitzer dealer and see the Wurlitzer dividually voiced diapason, reed, string and flute voices. 4037 and 4373. Play the eerie, switched-on sounds New linear accent controls permit you to increase or of synthesized music. Ask for your free Orbit III decrease the volume of selected sections suddenly, or demonstration record. Or write: Dept. T0-1272 WURLilzER® The Wurlitzer Company, DeKalb, Illinois 60115. ha.~the ,vay cover- photo ••• Sidney Torch at the Console of the Christie Organ, Regal Theatre, Edmonton. The glass panels surrounding the keyboards were illuminated by several sets of differently colored lights, controlled by motorized rheostats which created Journal of the American Theatre Organ Society different color effects as the lights were dimmed and brightened - an exclusive English feature! See the interview of Sidney Torch by Judd Walton and Frank Volume 14, No. -

ANALYSIS “The Waste Land” (1922) TS Eliot (1888-1965)

ANALYSIS “The Waste Land” (1922) T. S. Eliot (1888-1965) “[The essential meaning of the poem is reducible to four Sanskrit words, three of which are] so implied in the surrounding text that one can pass them by…without losing the general tone or the main emotion of the passage. They are so obviously the words of some ritual or other. [The reader can infer that “shantih” means peace.] For the rest, I saw the poem in typescript, and I did not see the notes till 6 or 8 months afterward; and they have not increased my enjoyment of the poem one atom. The poem seems to me an emotional unit…. I have not read Miss Weston’s Ritual to Romance, and do not at present intend to. As to the citations, I do not think it matters a damn which is from Day, which from Milton, Middleton, Webster, or Augustine. I mean so far as the functioning of the poem is concerned…. This demand for clarity in every particular of a work, whether essential or not, reminds me of the Pre-Raphaelite painter who was doing a twilight scene but rowed across the river in day time to see the shape of the leaves on the farther bank, which he then drew in with full detail.” Ezra Pound (1924) quoted by Hugh Kenner The Invisible Poet, T.S. Eliot (Obolensky 1959) 152 “[Eliot’s] trick of cutting his corners and his curves makes him seem obscure when he is clear as daylight. His thoughts move very rapidly and by astounding cuts. -

Volume 34, Number 07 (July 1916) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 7-1-1916 Volume 34, Number 07 (July 1916) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 34, Number 07 (July 1916)." , (1916). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/626 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ----- Price 15 Cents 1 473 THE ETUDE PRESSER’S MUSICAL MAGAZINE CONTENTS FOR JULY 1916 World of Music . Success Guides.G. if. Grecnhalyh A Practice Hour of Pleasure.C. W. London Can You Pass This Examination .'. The Part the Piano Should Pla^. .J. K. MacDonald The Layman's Attitude T W.’ R. Bpaldint Teaching Use of Bass Clef.Russell Carter 482 The Effect of Mechanical Ins :s Upon Musical jojuucu Lion.(Symposium) Royal Performers on the Flute. The Real Meaning of Rhythm.. .Lerou B. Campbell A Useful Finger Exercise.Wilbur F. Unger Discouraging the Pupil.Edna J. Warren Can There Be Any Real New Music?... How Parents Can Help...Geo. -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron. -

The Wisdom of Myth: Eliot's “Ulysses, Order, and Myth”

CHAPTER 14 The Wisdom of Myth: Eliot’s “Ulysses, Order, and Myth” James Nikopoulos No examination of the reception of the Greek and Roman classics by liter- ary modernism can ignore T. S. Eliot’s 1923 review, “Ulysses, Order, and Myth.” Its famous declaration that Joyce’s novel utilizes the story of the Odyssey as a means of giving order to “the immense panorama of futility and anarchy that is contemporary history” has been the starting point for discussions, not just of the classical legacy in early twentieth century literature, but for discussions of modernism as a whole.1 Eliot’s essay not only conditioned how we think of such paradigmatic modernist texts as The Waste Land and Ulysses; it condi- tioned how we think of modernity, of myth, and of the ever-expanding reasons for why the two should ever have been paired together in the first place. It begs asking why. “Ulysses, Order, and Myth” is one of Eliot’s most anthologized works of prose, and for many years, it was the most influential response to Ulysses.2 Most if not all examinations of Joyce’s novel are in some way a response to it. Perhaps this does not seem surprising, even if most critics today assert that the “mythical method” Eliot describes pertains more to his own work in The Waste Land than to anything Joyce had ever written. In a letter addressed to the editor of The Dial one month after “Ulysses, Order, and Myth” appeared, Eliot himself said that the piece was nothing to be proud of.3 To what then can we ascribe the enduring influence of such lamentable prose? While the answer has to do, in part, with the fame of both the author and the subject of the review, we should not discount the essay’s pithy wisdom either. -

Mausoleum Notes

Notes: Lines cross-referenced in the poem appear verbatim unless otherwise noted. Epigram Cf. The Sound and the Fury, William Faulkner Absence Line 1: Cf. “Keeping Things Whole,” Mark Strand: “In a field/I am the absence/of the field.” Line 14: Cf. “To the Reader,” Charles Baudelaire: trans. James McGowan. “Our sins are stubborn, our contrition lax” Lines 26-28: Adapted from “The Dead Flag Blues,” Godspeed You! Black Emperor. According to interviews, the spoken word section comes from an unfinished screenplay written by guitarist Efrim Menuck. “The car’s on fire, and there’s no driver at the wheel.” Lines 31-35: Cf. “Zone,” Guillaume Appolinare; trans. Ron Padgett. The lines in French read, “between the street Aumot-Thiéville and the avenue des Ternes.” Line 37: “Playing Possum,” Earl Sweatshirt (a.k.a. Thebe Neruda Kgositsile). The line is drawn from the name only. Lines 49-51: Cf. The Unquiet Grave, Cyril Connolly. “There are but two ways to be a good writer: like Homer, Shakespare or Goethe, to accept life completely, or like Pascal, Proust, Leopardi, Baudelaire, to refuse ever to loose sight of its horror.” Lines 53-55: Cf. Canto 3 of Dante Aligheri’s The Inferno. The translated lines read, “THROUGH ME THE WAY INTO ETERNAL SORROW./ THROUGH ME THE WAY AMONG THE LOST PEOPLE./ ABANDON ALL HOPE, YE WHO ENTER HERE.” Trans. Robert M. Durling. Capitalization original. These are words inscribed on the gates of hell. Lines 62-63: Cf. The Waste Land T.S. Eliot, “What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow” Lines 65-66: A common finger-picking technique among guitarists is to keep a quarter note pulse on the root note of a chord with your thumb. -

Tourisme Outaouais

OFFICIAL TOURIST GUIDE 2018-2019 Outaouais LES CHEMINS D’EAU THE OUTAOUAIS’ TOURIST ROUTE Follow the canoeist on the blue signs! You will learn the history of the Great River and the founding people who adopted it. Reach the heart of the Outaouais with its Chemins d’eau. Mansfield-et-Pontefract > Mont-Tremblant La Pêche (Wakefield) Montebello Montréal > Gatineau Ottawa > cheminsdeau.ca contents 24 6 Travel Tools regional overview 155 Map 8 Can't-miss Experiences 18 Profile of the Region 58 top things to do 42 Regional Events 48 Culture & Heritage 64 Nature & Outdoor Activities 88 Winter Fun 96 Hunting & Fishing 101 Additional Activities 97 112 Regional Flavours accommodation and places to eat 121 Places to Eat 131 Accommodation 139 useful informations 146 General Information 148 Travelling in Quebec 150 Index 153 Legend of Symbols regional overview 155 Map TRAVEL TOOLS 8 Can't-miss Experiences 18 Profile of the Region Bring the Outaouais with you! 20 Gatineau 21 Ottawa 22 Petite-Nation La Lièvre 26 Vallée-de-la-Gatineau 30 Pontiac 34 Collines-de-l’Outaouais Visit our website suggestions for tours organized by theme and activity, and also discover our blog and other social media. 11 Website: outaouaistourism.com This guide and the enclosed pamphlets can also be downloaded in PDF from our website. Hard copies of the various brochures are also available in accredited tourism Welcome Centres in the Outaouais region (see p. 146). 14 16 Share your memories Get live updates @outaouaistourism from Outaouais! using our hashtag #OutaouaisFun @outaouais