The Formation of the Alphabet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Reference Manual for the Standardization of Geographical Names United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names

ST/ESA/STAT/SER.M/87 Department of Economic and Social Affairs Statistics Division Technical reference manual for the standardization of geographical names United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names United Nations New York, 2007 The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environmental data and information on which Member States of the United Nations draw to review common problems and to take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of material in the present publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The term “country” as used in the text of this publication also refers, as appropriate, to territories or areas. Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. ST/ESA/STAT/SER.M/87 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. -

Kindergarten Readiness Assessment South Carolina Technical Report For

KINDERGARTEN READINESS ASSESSMENT SOUTH CAROLINA Technical Report 2018–2019 Kindergarten Readiness Assessment — South Carolina Technical Report 2018–2019 This report was prepared by: WestEd Standards, Assessment, and Accountability Services 730 Harrison Street San Francisco, CA 94107 Kindergarten Readiness Assessment — South Carolina Technical Report 2018–2019 CONTENTS 1 Overview .............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Purpose of the KRA ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose of This Report ................................................................................................................. 1 2 KRA Design ........................................................................................................................................... 1 2.1 Common Language Standards ..................................................................................................... 1 2.2 KRA Item Types............................................................................................................................. 1 2.3 KRA Blueprint ............................................................................................................................... 2 3 Item Analyses and IRT Scaling ............................................................................................................. 3 3.1 Classical Item -

A Global Leader in Pre-K–12 Education Technology

A global leader in pre-K–12 education technology ©Copyright 2020 Renaissance Learning Inc. All rights reserved. 1 Assessing for Kindergarten Readiness Isabel Turner July 14, 2021 ©Copyright 2020 Renaissance Learning Inc. All rights reserved. 2 “To accelerate learning for all children Our mission and adults of all ability levels and ethnic and social backgrounds, worldwide.” ©Copyright 2020 Renaissance Learning Inc. All rights reserved. 3 Agenda Defining Kindergarten Readiness 1 Purpose for screening K Readiness Assessment 2 Preparing your students, Supporting ELC’s, Student and Admin Experience 3 Support and Resources ©Copyright 2020 Renaissance Learning Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Defining Kindergarten Readiness Who takes the test? When do they test? Metrics • All public school and • Pre-Test in Fall • Kindergarten charter school K • July 22 – September 24 (test within first 30 school days) • Fall –SS 530 • All public Pre-K • Post –Test in Spring • Spring –SS 681 • All Collaborative Pre-K • March 21,2022 –April 29,2022 • Pre-K -Spring – SS 498 • School 500 K students • Key Dates Document ©Copyright 2020 Renaissance Learning Inc. All rights reserved. 5 Purpose for Universal Screening ©Copyright 2020 Renaissance Learning Inc. All rights reserved. 6 Star items are on the Star scale 300 900 Star items ©Copyright 2020 Renaissance Learning Inc. All rights reserved. 7 Learning progression skills are on the Star scale 675 Scaled Score (SS) 300 900 Star items Student performance Learning progression skills ©Copyright 2020 Renaissance Learning Inc. All rights reserved. 8 Basics of Star Early Literacy • Computer Adaptive • Designed for Pre-K - 3 grade non-readers • Assess within 3 domains (including early numeracy) • 27 items • Scores most closely align with a student’s age • Preferences are available ©Copyright 2020 Renaissance Learning Inc. -

Important Papers KRA Days and the First Days

We are very happy to welcome you to Marysville Schools and our Kindergarten program at Raymond Elementary! This is a wonderful time for you and your kindergartner! Whether this is your first child entering kindergarten or last, you should find the following letter filled with information to make those first days and weeks a bit easier. Our goal is for you to feel comfortable and have many of your questions answered before the first day of school. We are pleased to introduce our new kindergarten teacher, Mrs. Jess Gompf. Mrs. Gompf was a substitute teacher for the district last year and she also has experience teaching kindergarten at a private school. Her passion for students, strong work ethic and knowledge of kindergarten learning standards made her a stand out during the interview process! Our kindergartners will attend school on “red” days again this year. Please remember that the Red Class attends school on Mondays/Thursdays and alternating Wednesdays. You will want to refer to your Kindergarten Calendar for specific days and more information regarding our school calendar. We are including a copy of this calendar and it can also be found on the Marysville Schools website at www.marysville.k12.oh.us . Our families who are choosing the All Day/Everyday option will be attending Edgewood Elementary this year. We would also like to wish Mrs. Weiser the best of luck as she continues her career at Navin Elementary this year. Mrs. Weiser made the tough decision to move to Navin when an All Day/Every Day class became available. -

Armenian Alphabet Confusing Letters

Armenian Alphabet: Help to Distinguish the “Look-Alike” (confusing) 12 of the 38 Letters of the Armenian Alphabet 6. B b z zebra 27. A a j jet (ch) church 17. ^ 6 dz (adze) (ts) cats 25. C c ch church 19. ch unaspirated ch/j (j) jet Q q • 14. ts unaspirated ts/dz (dz) adze ) 0 • 21. & 7 h hot initial y Maya medial y final in monosyllable except verbs silent final elsewhere 35. W w p piano 36. @ 2 k kid 34. U u v violin 31. t step unaspirated t/d (d) dance K k • 38. ~ ` f fantastic ARMENIAN ALPHABET First created in the 5th c. by Mesrop Mashtots. Eastern Armenian Dialect Transliteration. (Western Dialect, when different, follows in parentheses). 1. a father 14. ts unaspirated ts/dz (dz) adze G g ) 0 • 2. E e b boy (p) piano 15. k skip unaspirated k/g (g) go I i • 3. D d g go (k) kid 16. L l h hot 4. X x d dance (t) ten 17. ^ 6 dz (adze) (ts) cats 5. F f ye yet initial e pen medial 18. * 8 gh Parisian French Paris e pen initial ft, fh, fh2, fr you are 19. ch unaspirated ch/j (j) jet Q q • y yawn before vowel 20. T t m meet 6. B b z zebra 21. h hot initial 7. e pen & 7 + = y Maya medial 8. O o u focus y final in monosyllable except verbs silent final elsewhere 9. P p t ten 22. H h n nut 10. -

Cataloging Service Bulletin 004, Spring 1979

- LIBRARY OF CONGRESS/WASHINGTON CATALOGING SERVICE BULLETIN PROCESSING SERVICES Number 4, Spring 1979 Editor: Robert M. Hiatt CONTENTS GENERAL Correspond.ence Ad.dressed. to the Library of Congress Indexes DESCRIPTIVE CATALOGING Correspondence of Interest to Other Librarians Rule Interpretations Revised Corporate Name Headings Cataloging of Videorecordings IFLA Draft Recommend.ations 6 '. SUBJECT HEADINGS Changing Subject Headings and Closing the Catalogs Policy on Policy Statements Multiples in LCSH " ~0rnpend.s" Subscriptions to and additional copies of Cataloging Sewice Bullelin are dvl\il - able upon request and at no charge from the Cataloging Distribution Servic.~.. - Library of Congress, Building 159, Navy Yard Annex, Washington, D.C. 20541. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78-51400 lSSN 0160-8029 Key title: Cataloging service bulletin CONTENTS (Cont 'd) LC CLASSIFICATION Classifying Works on Library Resources Erratm DECIMAL CLASSTFICATION Dewey 19 n 2 Cataloging Service Bulletin, No. 4 / Spring 1979 GENERAL Correspond.ence Addressed to the Library of Congress The Library of Congress welcomes inquiries regarding catalog- ing matters. In ord.er to exped.ite replies, please write directly to the LC officer responsible for the area of the inquiry, as ind.icated.below. Replies will be returned. as soon as practicable. This is a revision of the list that appeared. in Cataloging Service, bulletin 119. At the Library of Congress most cataloging is divid.ed, admin- istratively into d.escriptive cataloging and. subject cataloging. The term d.escriptive cataloging refers to the choice and form of the main entry heading, bibliographic das cription, and added entries (secondary entries numbered, with roman numerals), and. subject cataloging refers to subject head.ings (second.ary entries numbered, with arabic numerals) and, the LC classification system (includ.ing cuttering ) . -

John Howell for Books

John Howell for Books Muir Dawson’s Personal Library August 2013 John Howell for Books John Howell, member ABAA, ILAB, IOBA 5205 ½ Village Green, Los Angeles, CA 90016-5207 310 367-9720 www.johnhowellforbooks.com [email protected] THE FINE PRINT: All items offered subject to prior sale. Call or e-mail to reserve, or visit us at www.johnhowellforbooks.com. Check and PayPal payments preferred; credit cards accepted. Make checks payable to John Howell for Books. Paypal payments to: [email protected]. All items are guaranteed as described. Items may be returned within 10 days of receipt for any reason with prior notice to me. Prices quoted are in US Dollars. California residents will be charged applicable sales taxes. We request prepayment by new customers. Institutional requirements can be accomodated. Inquire for trade courtesies. Shipping and handling additional. All items shipped via insured USPS Mail. Expedited shipping available upon request at cost. Standard domestic shipping $ 5.00 for a typical octavo volume; additional items $ 2.00 each. Large or heavy items may require additional postage. We actively solitcit offers of books and ephemera to purchase, including estates, collections and consignments. Please inquire. A selection of books from Muir Dawson’s library. BOOK FAIRS: I will be showing at the following book fairs; passes available upon request: September 14, 2013 - Sacramento Antiquarian Book Fair October 5, 2013 - Los Angeles Printer’s Fair, Torrance CA October 12 and 13, 2013 - Seattle Antiquarian Book Fair John Howell for Books 3 1 AARON, William Metcalf. Italic Writing: A Concise Guide. New York: Transatlantic Arts, 1971. -

1 Symbols (2286)

1 Symbols (2286) USV Symbol Macro(s) Description 0009 \textHT <control> 000A \textLF <control> 000D \textCR <control> 0022 ” \textquotedbl QUOTATION MARK 0023 # \texthash NUMBER SIGN \textnumbersign 0024 $ \textdollar DOLLAR SIGN 0025 % \textpercent PERCENT SIGN 0026 & \textampersand AMPERSAND 0027 ’ \textquotesingle APOSTROPHE 0028 ( \textparenleft LEFT PARENTHESIS 0029 ) \textparenright RIGHT PARENTHESIS 002A * \textasteriskcentered ASTERISK 002B + \textMVPlus PLUS SIGN 002C , \textMVComma COMMA 002D - \textMVMinus HYPHEN-MINUS 002E . \textMVPeriod FULL STOP 002F / \textMVDivision SOLIDUS 0030 0 \textMVZero DIGIT ZERO 0031 1 \textMVOne DIGIT ONE 0032 2 \textMVTwo DIGIT TWO 0033 3 \textMVThree DIGIT THREE 0034 4 \textMVFour DIGIT FOUR 0035 5 \textMVFive DIGIT FIVE 0036 6 \textMVSix DIGIT SIX 0037 7 \textMVSeven DIGIT SEVEN 0038 8 \textMVEight DIGIT EIGHT 0039 9 \textMVNine DIGIT NINE 003C < \textless LESS-THAN SIGN 003D = \textequals EQUALS SIGN 003E > \textgreater GREATER-THAN SIGN 0040 @ \textMVAt COMMERCIAL AT 005C \ \textbackslash REVERSE SOLIDUS 005E ^ \textasciicircum CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT 005F _ \textunderscore LOW LINE 0060 ‘ \textasciigrave GRAVE ACCENT 0067 g \textg LATIN SMALL LETTER G 007B { \textbraceleft LEFT CURLY BRACKET 007C | \textbar VERTICAL LINE 007D } \textbraceright RIGHT CURLY BRACKET 007E ~ \textasciitilde TILDE 00A0 \nobreakspace NO-BREAK SPACE 00A1 ¡ \textexclamdown INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK 00A2 ¢ \textcent CENT SIGN 00A3 £ \textsterling POUND SIGN 00A4 ¤ \textcurrency CURRENCY SIGN 00A5 ¥ \textyen YEN SIGN 00A6 -

Fonts for Latin Paleography

FONTS FOR LATIN PALEOGRAPHY Capitalis elegans, capitalis rustica, uncialis, semiuncialis, antiqua cursiva romana, merovingia, insularis majuscula, insularis minuscula, visigothica, beneventana, carolina minuscula, gothica rotunda, gothica textura prescissa, gothica textura quadrata, gothica cursiva, gothica bastarda, humanistica. User's manual 5th edition 2 January 2017 Juan-José Marcos [email protected] Professor of Classics. Plasencia. (Cáceres). Spain. Designer of fonts for ancient scripts and linguistics ALPHABETUM Unicode font http://guindo.pntic.mec.es/jmag0042/alphabet.html PALEOGRAPHIC fonts http://guindo.pntic.mec.es/jmag0042/palefont.html TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER Page Table of contents 2 Introduction 3 Epigraphy and Paleography 3 The Roman majuscule book-hand 4 Square Capitals ( capitalis elegans ) 5 Rustic Capitals ( capitalis rustica ) 8 Uncial script ( uncialis ) 10 Old Roman cursive ( antiqua cursiva romana ) 13 New Roman cursive ( nova cursiva romana ) 16 Half-uncial or Semi-uncial (semiuncialis ) 19 Post-Roman scripts or national hands 22 Germanic script ( scriptura germanica ) 23 Merovingian minuscule ( merovingia , luxoviensis minuscula ) 24 Visigothic minuscule ( visigothica ) 27 Lombardic and Beneventan scripts ( beneventana ) 30 Insular scripts 33 Insular Half-uncial or Insular majuscule ( insularis majuscula ) 33 Insular minuscule or pointed hand ( insularis minuscula ) 38 Caroline minuscule ( carolingia minuscula ) 45 Gothic script ( gothica prescissa , quadrata , rotunda , cursiva , bastarda ) 51 Humanist writing ( humanistica antiqua ) 77 Epilogue 80 Bibliography and resources in the internet 81 Price of the paleographic set of fonts 82 Paleographic fonts for Latin script 2 Juan-José Marcos: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The following pages will give you short descriptions and visual examples of Latin lettering which can be imitated through my package of "Paleographic fonts", closely based on historical models, and specifically designed to reproduce digitally the main Latin handwritings used from the 3 rd to the 15 th century. -

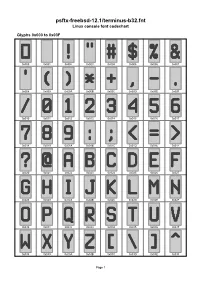

Psftx-Freebsd-12.1/Terminus-B32.Fnt Linux Console Font Codechart

psftx-freebsd-12.1/terminus-b32.fnt Linux console font codechart Glyphs 0x000 to 0x03F 0x000 0x001 0x002 0x003 0x004 0x005 0x006 0x007 0x008 0x009 0x00A 0x00B 0x00C 0x00D 0x00E 0x00F 0x010 0x011 0x012 0x013 0x014 0x015 0x016 0x017 0x018 0x019 0x01A 0x01B 0x01C 0x01D 0x01E 0x01F 0x020 0x021 0x022 0x023 0x024 0x025 0x026 0x027 0x028 0x029 0x02A 0x02B 0x02C 0x02D 0x02E 0x02F 0x030 0x031 0x032 0x033 0x034 0x035 0x036 0x037 0x038 0x039 0x03A 0x03B 0x03C 0x03D 0x03E 0x03F Page 1 Glyphs 0x040 to 0x07F 0x040 0x041 0x042 0x043 0x044 0x045 0x046 0x047 0x048 0x049 0x04A 0x04B 0x04C 0x04D 0x04E 0x04F 0x050 0x051 0x052 0x053 0x054 0x055 0x056 0x057 0x058 0x059 0x05A 0x05B 0x05C 0x05D 0x05E 0x05F 0x060 0x061 0x062 0x063 0x064 0x065 0x066 0x067 0x068 0x069 0x06A 0x06B 0x06C 0x06D 0x06E 0x06F 0x070 0x071 0x072 0x073 0x074 0x075 0x076 0x077 0x078 0x079 0x07A 0x07B 0x07C 0x07D 0x07E 0x07F Page 2 Glyphs 0x080 to 0x0BF 0x080 0x081 0x082 0x083 0x084 0x085 0x086 0x087 0x088 0x089 0x08A 0x08B 0x08C 0x08D 0x08E 0x08F 0x090 0x091 0x092 0x093 0x094 0x095 0x096 0x097 0x098 0x099 0x09A 0x09B 0x09C 0x09D 0x09E 0x09F 0x0A0 0x0A1 0x0A2 0x0A3 0x0A4 0x0A5 0x0A6 0x0A7 0x0A8 0x0A9 0x0AA 0x0AB 0x0AC 0x0AD 0x0AE 0x0AF 0x0B0 0x0B1 0x0B2 0x0B3 0x0B4 0x0B5 0x0B6 0x0B7 0x0B8 0x0B9 0x0BA 0x0BB 0x0BC 0x0BD 0x0BE 0x0BF Page 3 Glyphs 0x0C0 to 0x0FF 0x0C0 0x0C1 0x0C2 0x0C3 0x0C4 0x0C5 0x0C6 0x0C7 0x0C8 0x0C9 0x0CA 0x0CB 0x0CC 0x0CD 0x0CE 0x0CF 0x0D0 0x0D1 0x0D2 0x0D3 0x0D4 0x0D5 0x0D6 0x0D7 0x0D8 0x0D9 0x0DA 0x0DB 0x0DC 0x0DD 0x0DE 0x0DF 0x0E0 0x0E1 0x0E2 0x0E3 0x0E4 0x0E5 0x0E6 -

An Introduction to the New Testament Manuscripts and Their Texts

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE NEW TESTAMENT MANUSCRIPTS AND THEIR TEXTS This is the first major English-language introduction to the earliest manuscripts of the New Testament to appear for over forty years. An essential handbook for scholars and students, it provides a thorough grounding in the study and editing of the New Testament text combined with an emphasis on dramatic current developments in the field. Covering ancient sources in Greek, Syriac, Latin and Coptic, it * describes the manuscripts and other ancient textual evidence, and the tools needed to study them * deals with textual criticism and textual editing, describing modern approaches and techniques, with guidance on the use of editions * introduces the witnesses and textual study of each of the main sections of the New Testament, discussing typical variants and their significance. A companion website with full-colour images provides generous amounts of illustrative material, bringing the subject alive for the reader. d. c. parker is Edward Cadbury Professor of Theology in the Department of Theology and Religion and a Director of the Institute for Textual Scholarship and Electronic Editing, University of Birmingham. His publications include The Living Text of the Gospels (1997) and Codex Bezae: an Early Christian Manuscript and its Text (1992). AN INTRODUCTION TO THE NEW TESTAMENT MANUSCRIPTS AND THEIR TEXTS D. C. PARKER University of Birmingham CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521895538 © D. -

Ninidze, Mariam " a New Point of Vew on the Origin of the Georgian Alphabet"

Maia Ninidze A New Point of View on the Origin of the Georgian Alphabet The history of the development of different scripts shows that writing may assume the organized systemic appearance that Georgian asomtavruli (capital alphabet) had in the 5th century only as a result of reform. No graphic system has received such refined appearance through its independent evolution. Take, for example, the development of the Greek alphabet down to 403 B.C. In reconstructing the original script of the Georgian alphabet I was guided by the point of view that "the first features and the later developed or introduced foreign elements should be demarked and in this way comparative chronology be defined" (10, p. 50) and that "knowledge of the historical development of the outline of letters will enable us to form an idea of how the change of the outline of letters occurred and ... perceive the type of the preceding change, no imprints on monuments of which have come down to us" (12. p. 202). When one alphabet evinces similarity with another in the outline of corresponding graphemes of similar sounds, this suggests their common provenance or one's derivation from the other. But closeness existing at the level of general systemic peculiarities is a sign of later, artificial assimilation. The systemic similarity of Georgian asomtavruli with Greek would seem to suggest that it was reformed on the basis of the Greek counterpart. The earliest Georgian inscriptions in the asomtavruli are characterized by similarity to Greek in: 1) equal height of letters, 2) geometric roundness of graphemes and linearity-angularity, 3) the direction of writing from left to right, 4) the order of the alphabet and the numerical value of graphemes, but not similarity in the form of individual graphemes.