AFRICAN CITIES READER III Land, Property and Value

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education and the Struggle for National Liberation in South Africa

Education and the Struggle for National Liberation in South Africa Essays and speeches by Neville Alexander (1985–1989) Education and the Struggle for National Liberation in South Africa was first published by Skotaville Publishers. ISBN 0 947479 15 5 © Copyright Neville Alexander 1990 All rights reserved. This digital edition published 2013 © Copyright The Estate of Neville Edward Alexander 2013 This edition is not for sale and is available for non-commercial use only. All enquiries relating to commercial use, distribution or storage should be addressed to the publisher: The Estate of Neville Edward Alexander, PO Box 1384, Sea Point 8060, South Africa Contents Preface 3 What is happening in our schools and what can we do about it? 4 Ten years of educational crisis: The resonance of 1976 28 Liberation pedagogy in the South African context 52 Education, culture and the national question 71 The academic boycott: Issues and implications 88 The tactics of education for liberation 102 Education strategies for a new South Africa 115 The future of literacy in South Africa: Scenarios or slogans? 142 Careers in an apartheid society 152 Restoring the status of teachers in the community 164 Bursaries in South Africa: Factors to consider in drafting a five-year plan 176 A democratic language policy for a post-apartheid South Africa/Azania 188 African culture in the context of Namibia: Cultural development or assimilation? 205 PREFACE THE FOLLOWING ESSAYS AND SPEECHES have been selected from among numerous attempts to address the relationship between education and the national liberation struggle. All of them were written or delivered in the period 1985–1989, which has been one of the most turbulent periods in our recent history, more especially in the educational arena. -

Ceramics Monthly May93 Cei0

May 1993 1 William Hunt.......................................... Editor RuthC. Butler...................... Associate Editor Robert L. Creager......................Art Director Kim Nagorski..................... Assistant Editor Mary Rushley................Circulation Manager Mary E. Beaver ....Assistant Circulation Manager Connie Belcher............Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis............................... Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Nor thwest Boulevard Box 12448 Columbus, Ohio 43212 (614) 488-8236 FAX (614) 488-4561 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is pub lished monthly except July and August by Profes sional Publications, Inc., 1609 Northwest Bou levard, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second Class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates: One year $22, two years $40, three years $55. Add $10 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. Change of Address: Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Offices, Post Office Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, announcements, news releases, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (including 35mm slides), graphic illustrations and digital TIFF images are welcome and will be considered for publication. Mail submissions to Ceramics Monthly, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. We also accept unillustrated materials faxed to (614) 488-4561. Writing and Photographic Guidelines: A book let describing standards and procedures for sub mitting materials is available upon request. Indexing: An index of each year’s articles appears in the December issue. Additionally, Ceramics Monthly articles are indexed in the Art Index. Printed, on-line and CD-ROM (computer) index ing is available through Wilsonline, 950 Univer sity Avenue, Bronx, New York 10452; and from Information Access Company, 362 Lakeside Drive, Forest City, California 94404. -

The ONE and ONLY Ivan

KATHERINE APPLEGATE The ONE AND ONLY Ivan illustrations by Patricia Castelao Dedication for Julia Epigraph It is never too late to be what you might have been. —George Eliot Glossary chest beat: repeated slapping of the chest with one or both hands in order to generate a loud sound (sometimes used by gorillas as a threat display to intimidate an opponent) domain: territory the Grunt: snorting, piglike noise made by gorilla parents to express annoyance me-ball: dried excrement thrown at observers 9,855 days (example): While gorillas in the wild typically gauge the passing of time based on seasons or food availability, Ivan has adopted a tally of days. (9,855 days is equal to twenty-seven years.) Not-Tag: stuffed toy gorilla silverback (also, less frequently, grayboss): an adult male over twelve years old with an area of silver hair on his back. The silverback is a figure of authority, responsible for protecting his family. slimy chimp (slang; offensive): a human (refers to sweat on hairless skin) vining: casual play (a reference to vine swinging) Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Epigraph Glossary hello names patience how I look the exit 8 big top mall and video arcade the littlest big top on earth gone artists shapes in clouds imagination the loneliest gorilla in the world tv the nature show stella stella’s trunk a plan bob wild picasso three visitors my visitors return sorry julia drawing bob bob and julia mack not sleepy the beetle change guessing jambo lucky arrival stella helps old news tricks introductions stella and ruby home -

Download This PDF File

Podcasting as Activism and/or Entrepreneurship: Cooperative Networks, Publics and African Literary Production Madhu Krishnan; Kate Wallis University of Bristol; University of Exeter, UK In April 2017, we were present at a workshop titled “Personal Histories, Personal Archives, Alternative Print Cultures,” organized as part of the AHRC Research Network “Small Magazines, Literary Networks and Self-Fashioning in Africa and its Diasporas” (see Smit for a report on the session). The workshop was held at the now-defunct Long Street premises of Chimurenga, a self-described “project-based mutable object, publication, pan-African platform for editorial and curatorial work” based in Cape Town and best known for their eponymous magazine, which published sixteen issues between 2002 and 2011 (Chimurenga). As part of a conversation with collaborators Billy Kahora and Bongani Kona, editor Stacy Hardy was asked how Chimurenga sought out and forged readerships and publics. In her response, Hardy argued that the idea of a “target market” was “dangerous” and “arrogant,” offering a powerful repudiation to dominant models within the global publishing industry and book trade. Chimurenga, Hardy explained, worked from the premise articulated by founder Ntone Edjabe that “you don’t have to find readers, they find you.” Chimurenga’s ethos, Hardy explained, was one based on recognition, what she terms the “recognition of being part of something,” of “encountering Chimurenga and clocking into belonging” (Hardy, Kahora and Kona). Readers, for Hardy, were “Chimurenga people” who would find the publication and, on finding it, find something of themselves within it, be it through engagement with the magazine, attendance at Chimurenga’s live events and parties, or participation in the collective’s online presence. -

Prizing African Literature: Awards and Cultural Value

Prizing African Literature: Awards and Cultural Value Doseline Wanjiru Kiguru Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Stellenbosch University Supervisors: Dr. Daniel Roux and Dr. Mathilda Slabbert Department of English Studies Stellenbosch University March 2016 i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained herein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2016 Signature…………….………….. Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Dedication To Dr. Mutuma Ruteere iii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This study investigates the centrality of international literary awards in African literary production with an emphasis on the Caine Prize for African Writing (CP) and the Commonwealth Short Story Prize (CWSSP). It acknowledges that the production of cultural value in any kind of setting is not always just a social process, but it is also always politicised and leaning towards the prevailing social power. The prize-winning short stories are highly influenced or dependent on the material conditions of the stories’ production and consumption. The content is shaped by the prize, its requirements, rules, and regulations as well as the politics associated with the specific prize. As James English (2005) asserts, “[t]here is no evading the social and political freight of a global award at a time when global markets determine more and more the fate of local symbolic economies” (298). -

School Leadership Under Apartheid South Africa As Portrayed in the Apartheid Archive Projectand Interpreted Through Freirean Education

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2021 SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA AS PORTRAYED IN THE APARTHEID ARCHIVE PROJECTAND INTERPRETED THROUGH FREIREAN EDUCATION Kevin Bruce Deitle University of Montana, Missoula Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Deitle, Kevin Bruce, "SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA AS PORTRAYED IN THE APARTHEID ARCHIVE PROJECTAND INTERPRETED THROUGH FREIREAN EDUCATION" (2021). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11696. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11696 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA AS PORTRAYED IN THE APARTHEID ARCHIVE PROJECT AND INTERPRETED THROUGH FREIREAN EDUCATION By KEVIN BRUCE DEITLE Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Educational Leadership The University of Montana Missoula, Montana March 2021 Approved by: Dr. Ashby Kinch, Dean of the Graduate School -

Poetics and Politics in Contemporary African Travel Writing

Poetics and Politics in Contemporary African Travel Writing Maureen Amimo Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof Louise Green Co-supervisor: Prof Grace Musila March 2020 i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: ……………………………………… Copyright © 2020 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This study investigates contemporary travel narratives about Africa by Africans authors. Scholarship on travel writing about Africa has largely centred examples from the Global North, yet there is a rich body of travel writing by African authors. I approach African travel writing as an emerging genre that allows African authors to engage their marginality within the genre and initiate a transformative poetics inscribing alternative politics as viable forms of meaning-making. I argue that contemporary African travel writing stretches and redefines the aesthetic limits of the genre through experimentation which enables the form to carry the weight and complexities of African experiences. Drawing on the work of theorists such as Edward Said, Mary Louise Pratt, James Clifford and Syed Manzurul Islam, as well as local philosophy emergent from the texts, I examine the reimaginations of the form of the travel narrative, which centre African experiences. -

Section 5 Voices of the People: Case Studies of Medium-Density Housing

SECTION 5 VOICES OF THE PEOPLE: CASE STUDIES OF MEDIUM-DENSITY HOUSING SECTION 5: VOICES OF THE PEOPLE - CASE STUDIES OF MEDIUM-DENSITY HOUSING 189 VOICES OF THE PEOPLE: CASE STUDIES OF MEDIUM-DENSITY HOUSING 1. Overview Table 38: Overview of case studies Date of interviews Project Location Tenure with residents Spring Þeld Terrace Cape Town (South Africa) Sectional title (rental February 2005 and ownership) Carr Gardens Johannesburg (South Africa) Social rental April 2005 Newtown Housing Cooperative Johannesburg (South Africa) Cooperative housing February 2005 Stock Road Cape Town (South Africa) Installment sale March 2005 (eventual individual ownership) Missionvale Nelson Mandela Metro Individual ownership November 2004 (South Africa) Samora Machel Cape Town (South Africa) Individual ownership November 2004 Sakhasonke Village Nelson Mandela Metro Individual ownership March 2007 (South Africa) N2 Gateway – Joe Slovo (Phase1) Cape Town (South Africa) Social rental January 2008 Washington Heights Mutual New York (USA) Rental Housing Association Vashi Navi Mumbai (India) Cooperative housing Vitas Housing Project Manila, Tondo (Philippines) Rental and ownership The majority of South Africans were denied ensure a more equitable resource distribution. 1 human rights and essential livelihood resources for hundreds of years, especially under apartheid. In this regard, the case studies discussed look Since 1994 the country’s Þrst democratically at the extent and implications of community elected government has approved numerous laws participation in the development and imple- and policies, established development programmes, mentation processes of higher-density housing and rati Þed international treaties to ensure the projects. They explore prospects of approaching realisation of basic human rights, as de Þned in the the future delivery of higher-density housing in a South African Constitution. -

South Africa Tackles Global Apartheid: Is the Reform Strategy Working? - South Atlantic Quarterly, 103, 4, 2004, Pp.819-841

critical essays on South African sub-imperialism regional dominance and global deputy-sheriff duty in the run-up to the March 2013 BRICS summit by Patrick Bond Neoliberalism in SubSaharan Africa: From structural adjustment to the New Partnership for Africas Development – in Alfredo Saad-Filho and Deborah Johnstone (Eds), Neoliberalism: A Critical Reader, London, Pluto Press, 2005, pp.230-236. US empire and South African subimperialism - in Leo Panitch and Colin Leys (Eds), Socialist Register 2005: The Empire Reloaded, London, Merlin Press, 2004, pp.125- 144. Talk left, walk right: Rhetoric and reality in the New South Africa – Global Dialogue, 2004, 6, 4, pp.127-140. Bankrupt Africa: Imperialism, subimperialism and financial politics - Historical Materialism, 12, 4, 2004, pp.145-172. The ANCs “left turn” and South African subimperialism: Ideology, geopolitics and capital accumulation - Review of African Political Economy, 102, September 2004, pp.595-611. South Africa tackles Global Apartheid: Is the reform strategy working? - South Atlantic Quarterly, 103, 4, 2004, pp.819-841. Removing Neocolonialisms APRM Mask: A critique of the African Peer Review Mechanism – Review of African Political Economy, 36, 122, December 2009, pp. 595-603. South African imperial supremacy - Le Monde Diplomatique, Paris, May 2010. South Africas dangerously unsafe financial intercourse - Counterpunch, 24 April 2012. Financialization, corporate power and South African subimperialism - in Ronald W. Cox, ed., Corporate Power in American Foreign Policy, London, Routledge Press, 2012, pp.114-132. Which Africans will Obama whack next? – forthcoming in Monthly Review, January 2012. 2 Neoliberalism in SubSaharan Africa: From structural adjustment to the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Introduction Distorted forms of capital accumulation and class formation associated with neoliberalism continue to amplify Africa’s crisis of combined and uneven development. -

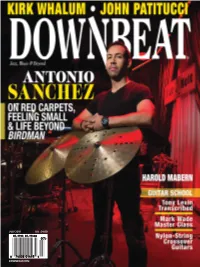

Downbeat.Com July 2015 U.K. £4.00

JULY 2015 2015 JULY U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT ANTONIO SANCHEZ • KIRK WHALUM • JOHN PATITUCCI • HAROLD MABERN JULY 2015 JULY 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 7 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

+| Download the Pdf Version

“Embracing Opacity” Interview with Ntone Edjabe (Chimurenga Magazine) Ntone Edjabe is the founder and editor of Chimurenga, a literary magazine produced in Cape Town focusing on contemporary African politics and popular culture. The title Chimurenga refers to the Shona word for ‘struggle’ as well as to a popular music genre in Zimbabwe. In this conversation on July 14th 2011, Edjabe looks back at the first decade of publishing Chimurenga and speaks about the philosophy underlying the publication. His current project, The Chimurenga Chronicle, takes on the form of a newspaper backdated to the week of May 11 – 18 2008, the period marked by the outbreak of so-called xenophobic violence in South Africa. In an effort to shift the perspective away from the confines of nation-states The Chimurenga Chronicle is produced in cooperation with independent publishers Kwani? in Kenya and Nigeria’s Cassava Republic Press. The newspaper will be released on October 19th 2011, the day known in South Africa as “Black Wednesday” since the historic day in 1977 when the apartheid regime declared 19 Black Consciousness organisations illegal and banned two newspapers. Subtitled “A speculative, future-forward newspaper that travels back in time to re-imagine the present”, The Chimurenga Chronicle engages with the call of theorist Achille Mbembe, to “imagine new forms of mobilization and leadership, to create an ‘intellectual plus-value’ based on a ‘concept-of-what-will-come’”. The first edition of Chimurenga was published in 2002. Approaching your 10th anniversary as a literary magazine, what are some of the changes and continuities characterising the Chimurenga publication? There was no clear strategy behind the project in the beginning, and I think that is perhaps one of the reasons why we are still here. -

New Labour Formations Organising Outside of Trade Unions, CWAO And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wits Institutional Repository on DSPACE Research Report for the degree of Master of Arts in Industrial Sociology, submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg Nkosinathi Godfrey Zuma Supervisor: Prof. Bridget C. Kenny Title: ‘Contingent organisation’ on the East Rand: New labour formations organising outside of trade unions, CWAO and the workers’ Solidarity Committee. Wits, Johannesburg, 2015 1 COPYRIGHT NOTICE The copyright of this research report rests with the University of the Witwaterand, Johannesburg, which it was submitted, in accordance with the University’s Intellectual Property Rights Procedures. No portion of this report may be produced or published without prior written authorization from the aurthor or the University. Extract of or qoutations from this research report may be included provided full acknowledgement of the aurthor and the University and in line with the University’s Intellectual Property Procedures. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My utmost appreciation goes to my supervisor Prof. Bridget Kenny for her endless intellectual guiedance and encouragement throughout this research report. It has been a great incalculable experience learning and be montored by Prof. Kenny. Without your support the complition of this report would be more difficult. I highly appreciate the warm welcome and support given to me by the Advice office (CWAO) in Germiston. My special thanks go to Ighsaan Schroeder for your support and permitting me access to your office. Thank you for the interviews you afforded me. Secondly, my special thanks go to Thabang Mohlala for your support and willingness to help me organise the interviews.