The Library and the Librarian As a Theme in Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Research, Library History and the Historiographical Imperative: Conceptual Reflections and Exploratory Observations Jean-Pierre V

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Libraries Faculty and Staff choS larship and Research Purdue Libraries 2016 To Honor Our Past: Historical Research, Library History and the Historiographical Imperative: Conceptual Reflections and Exploratory Observations Jean-Pierre V. M. Hérubel Purdue University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/lib_fsdocs Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Hérubel, Jean-Pierre V. M., "To Honor Our Past: Historical Research, Library History and the Historiographical Imperative: Conceptual Reflections and Exploratory Observations" (2016). Libraries Faculty and Staff Scholarship and Research. Paper 140. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/lib_fsdocs/140 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. To Honor Our Past: Historical Research, Library History and the Historiographical Imperative: Conceptual Reflections and Exploratory Observations Jean-Pierre V. M. Hérubel HSSE, University Libraries, Purdue University Abstract: This exploratory discussion considers history of libraries, in its broadest context; moreover, it frames the entire enterprise of pursuing history as it relates to LIS in the context of doing history and of doing history vis-à-vis LIS. Is it valuable intellectually for LIS professionals to consider their own history, writing historically oriented research, and what is the nature of this research within the professionalization of LIS itself as both practice and discipline? Necessarily conceptual and offering theoretical insight, this discussion perforce tenders the idea that historiographical innovations and other disciplinary approaches and perspectives can invigorate library history beyond its current condition. -

Who Runs the Library?

Who Runs the Library? The mission of most public libraries is to support the educational, recreational, and informational needs of the community. Everyone is welcome at the library, from the preschooler checking out his or her first book to the hobbyist looking for a 2 favorite magazine to the middle-aged breadwinner continuing her education by taking a class over the Internet. Providing a large number of services to meet the needs of a diverse population In This Trustee Essential requires a large supporting cast including trustees, the library director and staff, Responsibilities of the and representatives of the municipal government. When all members of the team library board know their responsibility and carry out their particular tasks, the library can run like a well-oiled machine. When one of the players attempts to take on the job of Responsibilities of the another, friction may cause a breakdown. library director The division of labor Responsibilities of the Library Board between the library director and the board The separate roles and responsibilities of each member of the team are spelled out in Wisconsin Statutes under Section 43.58, which is titled “Powers and Duties.” Responsibilities of the The primary responsibilities of trustees assigned here include: municipal government Exclusive control of all library expenditures. Purchasing of a library site and the erection of the library building when authorized. Exclusive control of all lands, buildings, money, and property acquired or leased by the municipality for library purposes. Supervising the administration of the library and appointing a librarian. Prescribing the duties and compensation of all library employees. -

The Unimagined: Catalogues and the Book of Sand in the Library of Babel

THE UNIMAGINED: CATALOGUES AND THE BOOK OF SAND IN THE LIBRARY OF BABEL w W. L. G. Bloch INTRODUCTION. We adore chaos because we love to produce order. M. C. Escher t’s an ironic joke that Borges would have appreciated: I am a mathematician who, lacking Spanish, perforce reads The Library I of Babel in translation. Furthermore, although I bring several thousand years of theory to bear on the story, none of it is literary theory! Having issued these caveats, it is my purpose to apply mathe- matical analysis to two ideas in the short story. My goal in this task is not to reduce the story in any capacity; rather it is to enrich and edify by glossing the intellectual margins and substructures. I sub- mit that because of his well-known affection for mathematics, ex- ploring the story through the eyes of a mathematician is a dynamic, useful, and necessary addition to the body of Borgesian thought. Variaciones Borges 19 (2005) 24 W. L. G. BLOCH In the first section, Information Theory: Cataloging the Collection, I consider the possible forms a Catalogue for the Library might take. Then, in Real Analysis: The Book of Sand, I apply elegant ideas from the 17th century and counter-intuitive ideas of the 20th century to the “Book of Sand” described in the final footnote of the story. Three variations of the Book, springing from three different interpretations of the phrase “infinitely thin,” are outlined. I request an indulgence from the reader. This introduction is writ- ten in the friendly and confiding first-person singular voice. -

Between Borges and Barthes a Text and Book Conundrum

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN (P): 2347-4564; ISSN (E): 2321-8878 Vol. 6, Issue 7, Jul 2018, 133-138 © Impact Journals BETWEEN BORGES AND BARTHES: A TEXT AND BOOK CONUNDRUM Muzaffar Karim Department of English, University of Kashmir, Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab, India Received: 05 Jul 2018 Accepted: 11 Jul 2018 Published: 16 Jul 2018 ABSTRACT In his story The Book of Sand, Borges defines the book as ‘infinite’ with no beginning and no end. In almost the same way when Barthes discusses his notion of text, in contrast to work, he defines text as ‘infinite deferment of the signified.’ Critically speaking Jorge Luis Borges’ short story The Book Of Sand and the kind of novel offered in the story The Garden of Forking Paths draw a clear resemblance and constantly comment on the Barthesian distinction between a ‘Work’ and a ‘Text’. This paper concerns itself with discussing Borges’ notion of ‘Book’ and proceeds to develop a contrast with the Roland Barthes conception of Work and Text. KEYWORDS: Work, Text, Borges, Barthes, Derrida, Blanchot, Author, Signified A book no longer belongs to a genre; every book pertains to literature alone. Maurice Blanchot 1 Literature is not exhaustible, for the sufficient and simple reason that a single book is not. A book is not an isolated entity: it is a narration, an axis of innumerable narrations. One literature differs from another, either before or after it, not so much because of the text as for the manner in which it is read. -

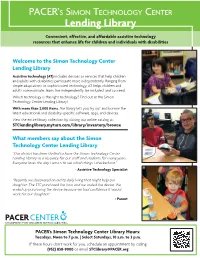

PACER's Simon Technology Center Lending Library

PACER’s simon TEChnology CEnTER Lending Library Convenient, effective, and affordable assistive technology resources that enhance life for children and individuals with disabilities Welcome to the Simon Technology Center Lending Library Assistive technology (AT) includes devices or services that help children and adults with disabilities participate more independently. Ranging from simple adaptations to sophisticated technology, AT helps children and adults communicate, learn, live independently, be included, and succeed. Which technology is the right technology? Find out at the Simon Technology Center Lending Library! With more than 2,000 items, the library lets you try out and borrow the latest educational and disability-specific software, apps, and devices. View the entire library collection by visiting our online catalog at: STClendinglibrary.myturn.com/library/inventory/browse What members say about the Simon Technology Center Lending Library “Our district has been thrilled to have the Simon Technology Center Lending Library as a resource for our staff and students for many years. Everyone loves the day I return to see which things I checked out.” - Assistive Technology Specialist “Recently we discovered an aid to daily living that might help our daughter. The STC purchased the item and we trialed the device. We ended up purchasing the device because we had confidence it would work for our daughter!” - Parent PACER’s Simon Technology Center Library Hours: Tuesdays, Noon to 7 p.m. | Select Saturdays, 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. If these hours -

Noumerous Sand

Peter Standish Numerous Sand t is part of the natural order of things for sand to get everywhere, whether we wish it or not. Into the literary world of Jorge Luis I Borges, however, it enters in a wholly artificial, intentional man- ner; it is even highlighted and thematised in the titles of at least two of his texts. Moreover, deserts abound in Borges’ stories, and there is some evidence that in general Borges was worried, even obsessed, by such open spaces. Estela Canto, in her book, Borges a contraluz, implies that his interest in open spaces verged on phobia. In her presence, he apparently dismissed the beach as a “terreno baldío donde la gente se pone en paños menores”—a wasteland where people go about in their underwear (50). One cannot know whether Canto is right in her inter- pretation of this antipathy (she speculates that Borges’ statement re- flected the fact that he himself was ill at ease and resented her own en- joyment of the beaches of her native Uruguay), but one can say with confidence that there are plenty of monstruous open spaces in Borges’ fictions and that they are quite frequently sandy. However, few critics have stopped to ponder upon the role of “arena” in Borges, or at- tempted to pin down the meanings associated with sand in the some- what rarified world of his literature.1 My purpose in this paper, then, is to explore some of the sandy areas, and in part my justification—a ba- nal one indeed in the ambit of literary criticism—is the assumption that this most elliptical of writers, this follower of Stevenson’s dictum that the only true art is one of omission, cannot have been making refer- ences to sand in a casual way. -

Positioning Library and Information Science Graduate Programs for 21St Century Practice

Positioning Library and Information Science Graduate Programs for 21st Century Practice Forum Report November 2017, Columbia, SC Compiled and edited by: Ashley E. Sands, Sandra Toro, Teri DeVoe, and Sarah Fuller (Institute of Museum and Library Services), with Christine Wolff-Eisenberg (Ithaka S+R) Suggested citation: Sands, A.E., Toro, S., DeVoe, T., Fuller, S., and Wolff-Eisenberg, C. (2018). Positioning Library and Information Science Graduate Programs for 21st Century Practice. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Museum and Library Services. Institute of Museum and Library Services 955 L’Enfant Plaza North, SW Suite 4000 Washington, DC 20024 June 2018 This publication is available online at www.imls.gov Positioning Library and Information Science Graduate Programs for 21st Century Practice | Forum Report II Table of Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Panels & Discussion ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Session I: Diversity in the Library Profession ....................................................................................... 3 Defining metrics and gathering data ............................................................................................... 4 Building professional networks through cohorts ........................................................................ 4 -

Ge Fei's Creative Use of Jorge Luis Borges's Narrative Labyrinth

Fudan J. Hum. Soc. Sci. DOI 10.1007/s40647-015-0083-x ORIGINAL PAPER Imitation and Transgression: Ge Fei’s Creative Use of Jorge Luis Borges’s Narrative Labyrinth Qingxin Lin1 Received: 13 November 2014 / Accepted: 11 May 2015 © Fudan University 2015 Abstract This paper attempts to trace the influence of Jorge Luis Borges on Ge Fei. It shows that Ge Fei’s stories share Borges’s narrative form though they do not have the same philosophical premises as Borges’s to support them. What underlies Borges’s narrative complexity is his notion of the inaccessibility of reality or di- vinity and his understanding of the human intellectual history as epistemological metaphors. While Borges’s creation of narrative gap coincides with his intention of demonstrating the impossibility of the pursuit of knowledge and order, Ge Fei borrows this narrative technique from Borges to facilitate the inclusion of multiple motives and subject matters in one single story, which denotes various possible directions in which history, as well as story, may go. Borges prefers the Jungian concept of archetypal human actions and deeds, whereas Ge Fei tends to use the Freudian psychoanalysis to explore the laws governing human behaviors. But there is a perceivable connection between Ge Fei’s rejection of linear history and tradi- tional storyline with Borges’ explication of epistemological uncertainty, hence the former’s tremendous debt to the latter. Both writers have found the conventional narrative mode, which emphasizes the telling of a coherent story having a begin- ning, a middle, and an end, inadequate to convey their respective ideational intents. -

ARL Cataloger Librarian Roles and Responsibilities Now and in the Future Jeanne M

Collections and Technical Services Publications and Collections and Technical Services Papers 2014 ARL Cataloger Librarian Roles and Responsibilities Now and In the Future Jeanne M. K. Boydston Iowa State University, [email protected] Joan M. Leysen Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/libcat_pubs Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ libcat_pubs/59. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Collections and Technical Services at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Collections and Technical Services Publications and Papers by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARL Cataloger Librarian Roles and Responsibilities Now and In the Future Abstract This article details the results of a 2011 study of cataloger librarians’ changing roles and responsibilities at academic Association of Research Libraries. The tudys participants, cataloging department heads, report that cataloger librarian roles are expanding to include cataloging more electronic resources and local hidden collections in addition to print materials. They ra e also creating non-MARC metadata. The increased usage of vendor products and services is also affecting the roles of cataloger librarians at some institutions. The ra ticle explores what skills cataloger librarians will need in the future and how libraries are providing training for that future. -

Kindle Books at Your Library

Kindle Books at Your Library Check out FREE Ebooks for your Kindle! (You must have an account with Amazon and a registered Kindle device orKindle app for PC, Mac, Android, iPhone, iPad, iPod, Blackberry or Windows Phone 7.) Here’s how: Go to the library’s website at www.daytonmetrolibrary.org Click on the Downloadables link: (Found on the upper right side of the site.) Select items to check out in the Kindle format. Basic Search Use the search box at the top of the page to find a specific item by typing a search term in the search box. Click on the magnifying glass. When the results are returned, click on the ‘Kindle Books’ filter on the left side of the page. Advanced Search If you would like to browse all of the ebooks available in the Kindle format you can click on Advanced Search. 1. Select Kindle as the format. 2. If you only want to see titles currently available for check out, click on ‘Available Now’. 3. Then click the search button, this will display all titles available for the Kindle. Check out items for Kindle format. Once you have found a title you would like to check out, you need to look for a few things: 1. Is there a copy available for check out? If the title is not available you can request the item. To request an unavailable item you click on ‘Place a Hold’. You will be prompted for your library card number and pin to login. Overdrive will ask for you to confirm your email address. -

Worlds of Libraries: Metafictional Works by Arlt, Borges, Bermani, and De Santis Cynthia Gabbay University of Haifa

Worlds of Libraries: Metafictional Works by Arlt, Borges, Bermani, and De Santis Cynthia Gabbay University of Haifa La historia suele quemar la historia. Y nos transformamos en la sombra que se apaga 241 con la letra. Las bibliotecas pueden ser una prisión, un refugio, o una hoguera. Emmanuel Taub, “Tesis sobre la escritura” The culture of Spanish America was marked by the white man’s effacement of the indigenous cultures when the colonizers occupied the lands of “the New World.” Occupiers saw the Mayan and Aztec cultures as meaningless and pagan. Led first by Hernán Cortés (1519), they set fire to texts of the Mayas, Aztecs, Zapotecs, and Mixtecs. In 1529, at Tlatelolco, Juan de Zumárraga, who was by then New Spain’s Bishop, ordered whole archives containing folk tales, works of history, science, eco- nomics, agriculture, theology, and astronomy, as well as holy scriptures, to be burned. Polastron describes the holocaust of the indigenous archives: Juan de Zumárraga, Bishop of Mexico, then high inquisitor of Spain outside the walls between 1536 and 1543, proudly burned all the Aztec codices that the conflagration of Cortez had missed—all the tonalamatl, the sacred books that he sent his agents to collect or that where found gathered together in amoxcalli, the halls of archives. […] Thus in 1529, Zumárraga had the library of the “most cultivated capital in Anahuac, and the great depository of the national libraries”1 brought to the market square of Tlatelolco until they formed “a mountain heap,” which the monks approached, brandishing their torches and singing. Thousands of polychrome pages went up in smoke. -

CIRCULATION the Library's Combined Circulation And

CIRCULATION The Library’s combined Circulation and Information Counter is located centrally on the first floor of the LRC. This is where the checkout desk is, near the center of the library on the 1st floor. Open during library hours. If a staff member has stepped away from the desk, please ring the bell. Entrance into the Library is through a security system portal in front of the counter. In addition to the 24- hour book drop accessible from outside, another book drop is located in this counter. INTERLIBRARY LOANS We will gladly locate and deliver you material not available in the WTC Library, which may be requested from other libraries. This is a free service reserved only for WTC faculty, registered students, and staff. Requested, photocopied periodical articles and book pages are complimentary and usually sent back by e-mail to the patron through the interlibrary loan process as a PDF. Loan requests are fulfilled at varying lengths of time. Please ask the librarian on duty or someone at the circulation desk for assistance. RESERVES Instructors may place materials on reserve at the library behind the circulation desk and specify how long students can use these items. Generally students can make copies or use the item within the library building. For more information, you can call the library at 325-574-7678 or email us at [email protected]. E-READERS Kindle Fire Available now for 2 hour checkout Newly loaded e-books Movies, apps, games, music, reading and more, plus Amazon’s revolutionary, cloud-accelerated web browser Vibrant color touch screen with extra-wide viewing angle Fast, powerful dual-core processor WESTERN TEXAS COLLEGE LIBRARY IN-HOUSE LOAN POLICY FOR ELECTRONIC DEVICES The WTC Library offers Netbook laptops for use within.