54877 GPNC GP Waterbirds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Bolivian Record of Laughing Gull Leucophaeus Atricilla, and Two Noteworthy Records of Fulica Coots from Laguna Guapilo, Dpto

Cotinga 41 First Bolivian record of Laughing Gull Leucophaeus atricilla, and two noteworthy records of Fulica coots from Laguna Guapilo, dpto. Santa Cruz Matthew L. Brady, Anna E. Hiller, Damián I. Rumiz, Nanuq L. Herzog-Hamel and Sebastian K. Herzog Received 30 November 2018; fnal revision accepted 29 April 2019 Cotinga 41 (2019): 98–100 published online 21 June 2019 El 28 de enero de 2018, durante una visita a laguna Guapilo, al este de Santa Cruz de la Sierra, depto. Santa Cruz, Bolivia, observamos una Gaviota Reidora Leucophaeus atricilla, el primer registro en Bolivia. Adicionalmente, observamos comportamiento indicativo de anidación de la Gallareta Chica Fulica leucoptera, una especie que se consideraba como visitante no reproductiva en Bolivia, así como una Gallareta Andina Fulica ardesiaca, el primer registro para el depto. Santa Cruz. La reproducción de F. leucoptera en la laguna Guapilo fue confrmada el 5 de mayo de 2018 mediante la fotografía de un polluelo. On 28 January 2018, MLB, AEH, NLH-H and We aged the bird during the observation SKH observed several notable birds at Laguna based on the following combination of characters: Guapilo (17°46’50”S 63°05’48”W), a semi-urban uniformly dark primaries, without the white apical park 8.9 km east of Santa Cruz city centre, dpto. spots typical of older birds; a dark tail-band; Santa Cruz, Bolivia. The habitat is dominated by a extensive ash-grey neck and breast; and worn, c.35-ha lagoon, with dense mats of reeds and water brownish wing-coverts. These features are typical hyacinth Eichhornia crassipes at the edges, and of an advanced frst-year L. -

Middlesex University Research Repository an Open Access Repository Of

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Beasley, Emily Ruth (2017) Foraging habits, population changes, and gull-human interactions in an urban population of Herring Gulls (Larus argentatus) and Lesser Black-backed Gulls (Larus fuscus). Masters thesis, Middlesex University. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/23265/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Coyote Reservoir & Harvey Bear..…

Coyote Reservoir & Harvey Bear..…. February 24, south Santa Clara County Quick Overview – Watching the weather reports we all saw the storm coming, but a group of adventurous souls arrived with all their rain gear and ready to go regardless of the elements, and what a day we had! Once east of Gilroy and traveling through the country roads we realized that soaking wet birds create unique ID challenges. With characteristic feathers in disarray and the wet plumages now appearing much darker we had to leave some questionable birds off our list. We had wanted to walk some of the trails that make up the new Harvey Bear Ranch Park, but the rain had us doing most of our birding from the cars which was easy along Coyote Reservoir Road as it parallels the lake. It also makes it easy when no one else is in the park. We could stop anywhere we wanted and we were not in anyone’s way – a birder’s dream come true! Watching Violet Green Swallows by the hundreds reminded us all that spring is near. And at one stop we got four woodpecker species. Ending our day watching Bald Eagles grasp fish at the surface of the water was worth our getting all wet! And I’ll not soon forget our close encounter with the dam’s Rufous Crowned Sparrow. Since we started our day at the south entrance of the park we ended Rufous Crowned Sparrow our day at the north entrance. It was here we listened to above and hard working Western Meadowlarks and watched a Say’s Phoebe. -

Castle Green Bird List

GREEN CASTLE ESTATE Bird List Birds seen on recent tours during November – April | In one week we can expect around 120 species. E=Endemic | ES=Endemic Subspecies | I=Introduced Some of the species below are very unusual however they have been included for completeness. Jamaica has recorded over 300 species and the birds below are the most frequently encountered, however we cannot guarantee what we will or will not see, that’s birding! West Indian Whistling-Duck Lesser Yellowlegs Greater Antillean Elaenia (ES) Blue-winged Teal Whimbrel Jamaican Pewee (E) Northern Shoveler Ruddy Turnstone Sad Flycatcher (E) Ring-necked Duck Red Knot Rufous-tailed Flycatcher (E) Lesser Scaup Sanderling Stolid Flycatcher (ES) Masked Duck Semipalmated Sandpiper Gray Kingbird Ruddy Duck Western Sandpiper Loggerhead Kingbird (ES) Least Grebe Least Sandpiper Jamaican Becard (E) Pied-billed Grebe White-rumped Sandpiper Jamaican Vireo (E) White-tailed Tropicbird Baird's Sandpiper Blue Mountain Vireo (E) Magnificent Frigatebird Stilt Sandpiper Black-whiskered Vireo Brown Booby Short-billed Dowitcher Jamaican Crow (E) Brown Pelican Laughing Gull Caribbean Martin American Bittern Least Tern Tree Swallow Least Bittern Gull-billed Tern Northern Rough-winged Swallow Great Blue Heron Caspian Tern Cave Swallow (ES) Great Egret Royal Tern Barn Swallow Snowy Egret Sandwich Tern Rufous-throated Solitaire (ES) Little Blue Heron Rock Pigeon (I) White-eyed Thrush (E) Tricolored Heron White-crowned Pigeon White-chinned Thrush (E) Reddish Egret Plain Pigeon (ES) Gray Catbird Cattle -

First Record of a California Gull for North Carolina

General Field Notes LYNN MOSELEY EIS M. OSYE rth Crln Edtr Sth Crln Edtr prtnt f l prtnt f l Glfrd Cll h Ctdl Grnbr, C 240 Chrltn, SC 240 OICE Publication of any unusual sightings of birds in the Field Notes or Briefs for the Files does not imply that these reports have been accepted into the official Checklist of Birds records for either North or South Carolina. Decisions regarding the official Checklists are made by the respective State Records Committees and will be reported upon periodically in THE CHAT. rt rd f Clfrn Gll fr rth Crln Stephen J. Dinsmore John O. Fussell Jeremy Nance 2600 Glen Burnie 1412 Shepard Street 3259 N 1st Avenue Raleigh, NC 27607 Morehead City, NC 28557 Tucson, AZ 85719 At approximately 1400 h on 29 January 1993, we observed an adult California Gull (Larus californicus) at the Carteret County landfill, located southwest of Newport, North Carolina. We were birding the northwest corner of the landfill when Fussell called our attention to a slightly darker-mantled gull resting with hundreds of other gulls, mostly Herring Gulls (L. argentatus). We immediately recognized the bird as an adult California Gull. We were able to observe and photograph the bird for the nest half hour at distances of 75-100 m. At 1430 the bird suddenly flew south over the dump and we were not able to relocated it over the next 2 hours. Sprn 6 The following is a detailed description of the bird, much of it written immediately after the sighting. The bird was slightly smaller and slimmer than the numerous Herring Gulls surrounding it. -

Belize), and Distribution in Yucatan

University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland Institut of Zoology Ecology of the Black Catbird, Melanoptila glabrirostris, at Shipstern Nature Reserve (Belize), and distribution in Yucatan. J.Laesser Annick Morgenthaler May 2003 Master thesis supervised by Prof. Claude Mermod and Dr. Louis-Félix Bersier CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1. Aim and description of the study 2. Geographic setting 2.1. Yucatan peninsula 2.2. Belize 2.3. Shipstern Nature Reserve 2.3.1. History and previous studies 2.3.2. Climate 2.3.3. Geology and soils 2.3.4. Vegetation 2.3.5. Fauna 3. The Black Catbird 3.1. Taxonomy 3.2. Description 3.3. Breeding 3.4. Ecology and biology 3.5. Distribution and threats 3.6. Current protection measures FIRST PART: BIOLOGY, HABITAT AND DENSITY AT SHIPSTERN 4. Materials and methods 4.1. Census 4.1.1. Territory mapping 4.1.2. Transect point-count 4.2. Sizing and ringing 4.3. Nest survey (from hide) 5. Results 5.1. Biology 5.1.1. Morphometry 5.1.2. Nesting 5.1.3. Diet 5.1.4. Competition and predation 5.2. Habitat use and population density 5.2.1. Population density 5.2.2. Habitat use 5.2.3. Banded individuals monitoring 5.2.4. Distribution through the Reserve 6. Discussion 6.1. Biology 6.2. Habitat use and population density SECOND PART: DISTRIBUTION AND HABITATS THROUGHOUT THE RANGE 7. Materials and methods 7.1. Data collection 7.2. Visit to others sites 8. Results 8.1. Data compilation 8.2. Visited places 8.2.1. Corozalito (south of Shipstern lagoon) 8.2.2. -

Nesting Populations of California and Ring-Billed Gulls in California

WESTERN BIR Volume 31, Number 3, 2000 NESTING POPULATIONS OF CLwO AND RING-BI--F-r GULLS IN CALIFORNIA: RECENT SURVEYS AND HISTORICAL STATUS W. DAVID SHUFORD, Point Reyes Bird Observatory(PRBO), 4990 Shoreline Highway, StinsonBeach, California94970 THOMAS P. RYAN, San FranciscoBay Bird Observatory(SFBBO), P.O. Box 247, 1290 Hope Street,Alviso, California 95002 ABSTRACT: Statewidesurveys from 1994 to 1997 revealed33,125 to 39,678 breedingpairs of CaliforniaGulls and at least9611 to 12,660 pairsof Ring-billed Gullsin California.Gulls nested at 12 inland sitesand in San FranciscoBay. The Mono Lake colonywas by far the largestof the CaliforniaGull, holding 70% to 80% of the statepopulation, followed by SanFrancisco Bay with 11% to 14%. ButteValley WildlifeArea, Clear Lake NationalWildlife Refuge, and Honey Lake WildlifeArea were the only othersites that heldover 1000 pairsof CaliforniaGulls. In mostyears, Butte Valley, Clear Lake, Big Sage Reservoir,and Honey Lake togetherheld over 98% of the state'sbreeding Ring-billed Gulls; Goose Lake held9% in 1997. Muchof the historicalrecord of gullcolonies consists of estimatestoo roughfor assessmentof populationtrends. Nevertheless, California Gulls, at least,have increased substantially in recentdecades, driven largely by trendsat Mono Lake and San FranciscoBay (first colonizedin 1980). Irregularoccupancy of some locationsreflects the changing suitabilityof nestingsites with fluctuatingwater levels.In 1994, low water at six sites allowedcoyotes access to nestingcolonies, and resultingpredation appeared to reducenesting success greatly at threesites. Nesting islands secure from predators and humandisturbance are nestinggulls' greatest need. Conover(1983) compileddata suggestingthat breedingpopulations of Ring-billed(Larus delawarensis)and California(Larus californicus)gulls haveincreased greafiy in the Westin recentdecades. Detailed assessments of populationstatus and trends of these speciesin individualwestern states, however,have been publishedonly for Washington(Conover et al. -

BIRD CONSERVATION the Magazine of American Bird Conservancy Fall 2012 BIRD’S EYE VIEW

BIRD CONSERVATION The Magazine of American Bird Conservancy Fall 2012 BIRD’S EYE VIEW Is Species Conservation Enough? How should we as conservationists decide which birds deserve protection? Where should we draw the line that tells us which groups of birds are “unique” enough to merit saving? t one extreme, a conserva- becomes extinct? Do we care about tion skeptic might insist that the continuation of these evolution- Apreserving one type of bird ary processes, or do we take a pass from each genus is sufficient. At the on preserving them because these other, passionate lovers of wildlife birds are not sufficiently “unique”? may not accept the loss of even one When in doubt about whether to individual. A more typical birder take conservation action, I fall back might nominate the species as the on the precautionary principle, key conservation level because the which says, in essence, that when concept of species is familiar to us. l American Dipper: USFWS uncertain about the potential harm- Science gets us closer to the answers, ful effect of an action, the prudent but it cannot draw the line: the purpose of science is course is the conservative one. or, as aldo Leopold to gather knowledge, not to make decisions for us. wrote, “Save all of the pieces.” Furthermore, like life itself, the science of taxonomy is I say, save the Black Hills Dipper regardless of which in a constant state of change. Baltimore and Bullock’s taxonomic opinion prevails; and while we are at it, we Orioles have been “lumped” into Northern Oriole and ought to save Wayne’s Warbler, the rhododendron- then “split” again, all based on the most current scien- dwelling Swainson’s Warbler, and the tree-nesting tific opinion. -

Role of Habitat in the Distribution and Abundance of Marsh Birds

s 542 .18 S74 no.;43 1965 Role of Habitat in the Distribution and Abundance of Marsh Birds by Milton W. Weller and Cecil S. Spatcher Department of Zoology and Entomology Special Report No. 43 Agricultural and Home Economics Experiment Station Iowa State University of Science and Technology Ames, Iowa- April 1965 IOWA STATE TRA YEUNG LIBRARY DES MOlNESt 'IOWA CONTENTS Summary ---------------------- -- --------------------------------------- --- ------------------------------ --- ----------- 4 Introduction ------------------- ---- ------ --- -------- ----- ------------------------------ ---------------------- --- ---- 5 Study areas --------- -- --- --- --- -------------------------------- ---------------------- ----------------------- --------- 5 Methods ----------- --- ----------- --------- ------------------------------------------------------- --- -------------------- 6 Vegetation ---------------------------- ------------ --- -------------------------- --- ------------------ -- -------- 6 Bird populations ---------------------------------------------------------------- -------------------------- 6 Results ______ _ __ ____ __ _ __ ___ __ __ __ ______ __ ___ ___ __ _ _ _ ____ __ __ ___ __ ______ __ __ _____ ______ ____ ___ __ _ _ ____ ___ _____ __ __ ___ ___ _ 6 Species composition and chronology of nesting -------------------------------------- 6 Habitat changes at Little Wall and Goose lakes ------ -------------------------------- 8 Bird populations in relation to habitat ----------- ---- ----------- -------------------------- 11 Distribution -

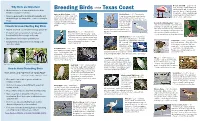

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large -

Great Egret Ardea Alba

Great Egret Ardea alba Joe Kosack/PGC Photo CURRENT STATUS: In Pennsylvania, the great egret is listed state endangered and protected under the Game and Wildlife Code. Nationally, they are not listed as an endangered/threatened species. All migra- tory birds are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. POPULATION TREND: The Pennsylvania Game Commission counts active great egret (Ardea alba) nests in every known colony in the state every year to track changes in population size. Since 2009, only two nesting locations have been active in Pennsylvania: Kiwanis Lake, York County (fewer than 10 pairs) and the Susquehanna River’s Wade Island, Dauphin County (fewer than 200 pairs). Both sites are Penn- sylvania Audubon Important Bird Areas. Great egrets abandoned other colonies along the lower Susque- hanna River in Lancaster County in 1988 and along the Delaware River in Philadelphia County in 1991. Wade Island has been surveyed annually since 1985. The egret population there has slowly increased since 1985, with a high count of 197 nests in 2009. The 10-year average count from 2005 to 2014 was 159 nests. First listed as a state threatened species in 1990, the great egret was downgraded to endan- gered in 1999. IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS: Great egrets are almost the size of a great blue heron (Ardea herodias), but white rather than gray-blue. From bill to tail tip, adults are about 40 inches long. The wingspan is 55 inches. The plumage is white, bill yellowish, and legs and feet black. Commonly confused species include cattle egret (Bubulus ibis), snowy egret (Egretta thula), and juvenile little blue herons (Egretta caerulea); however these species are smaller and do not nest regularly in the state. -

Aberrant Plumages in Grebes Podicipedidae

André Konter Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae An analysis of albinism, leucism, brown and other aberrations in all grebe species worldwide Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae in grebes plumages Aberrant Ferrantia André Konter Travaux scientifiques du Musée national d'histoire naturelle Luxembourg www.mnhn.lu 72 2015 Ferrantia 72 2015 2015 72 Ferrantia est une revue publiée à intervalles non réguliers par le Musée national d’histoire naturelle à Luxembourg. Elle fait suite, avec la même tomaison, aux TRAVAUX SCIENTIFIQUES DU MUSÉE NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE DE LUXEMBOURG parus entre 1981 et 1999. Comité de rédaction: Eric Buttini Guy Colling Edmée Engel Thierry Helminger Mise en page: Romain Bei Design: Thierry Helminger Prix du volume: 15 € Rédaction: Échange: Musée national d’histoire naturelle Exchange MNHN Rédaction Ferrantia c/o Musée national d’histoire naturelle 25, rue Münster 25, rue Münster L-2160 Luxembourg L-2160 Luxembourg Tél +352 46 22 33 - 1 Tél +352 46 22 33 - 1 Fax +352 46 38 48 Fax +352 46 38 48 Internet: http://www.mnhn.lu/ferrantia/ Internet: http://www.mnhn.lu/ferrantia/exchange email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Page de couverture: 1. Great Crested Grebe, Lake IJssel, Netherlands, April 2002 (PCRcr200303303), photo A. Konter. 2. Red-necked Grebe, Tunkwa Lake, British Columbia, Canada, 2006 (PGRho200501022), photo K. T. Karlson. 3. Great Crested Grebe, Rotterdam-IJsselmonde, Netherlands, August 2006 (PCRcr200602012), photo C. van Rijswik. Citation: André Konter 2015. - Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae - An analysis of albinism, leucism, brown and other aberrations in all grebe species worldwide. Ferrantia 72, Musée national d’histoire naturelle, Luxembourg, 206 p.